扩展功能

文章信息

- 刘忠斌, 龙伟, 黄嘉玲, 徐依萍, 葛颂

- LIU Zhongbin, LONG Wei, HUANG Jialing, XU Yiping, GE Song

- 牙龈卟啉单胞菌外膜囊泡与阿尔茨海默病的相关性研究进展

- Relationship between Porphyromonas gingivalis outer membrane vesicles and Alzheimer's disease: a review

- 微生物学通报, 2023, 50(8): 3647-3658

- Microbiology China, 2023, 50(8): 3647-3658

- DOI: 10.13344/j.microbiol.china.221087

-

文章历史

- 收稿日期: 2022-11-03

- 接受日期: 2022-12-24

- 网络首发日期: 2023-02-03

阿尔茨海默病(Alzheimer’s disease, AD)是一种慢性神经退行性疾病,在老年痴呆症中最常见。目前,全世界约有5 000万痴呆症患者,预计到2050年将增加2倍[1]。AD发病率逐年增加,严重威胁中老年人身体健康和生活质量,给患者家庭和社会带来了巨大的经济负担和社会压力。

牙周炎是由多种致病菌引发的慢性感染性疾病,是成年人中最常见的口腔感染之一。牙龈卟啉单胞菌(Porphyromonas gingivalis)作为牙周炎的关键致病菌,在其生长过程中可产生大量毒力因子,包括脂多糖(lipopolysaccharide, LPS)、牙龈素、菌毛、外膜囊泡(outer membrane vesicle, OMV)等[2-3]。细菌或其毒力因子既可直接损伤牙周组织,又可通过诱导宿主免疫反应间接损伤牙周组织,引起牙周组织慢性炎症,导致牙周袋的形成和牙槽骨的吸收,最终导致牙齿的松动、脱落。在牙周炎过程中,局部产生的细胞因子和促炎产物,可经溃疡的牙周袋内壁上皮扩散到全身循环,引发多种包括AD、心血管疾病及糖尿病等系统性疾病[4]。

OMV是P. gingivalis生长过程中产生的相对较小、离散的球形膜状结构。OMV由脂质、外膜蛋白(outer membrane protein, OMP)、周质蛋白和核酸等组成,直径为50−250 nm,约为P. gingivalis直径的7%[5],与亲本细菌相比,OMV可更好地穿透深层组织。OMV还浓缩了亲本细菌的LPS、牙龈素及菌毛等大量毒力因子,并可能在牙周病和AD中发挥重要作用[6]。

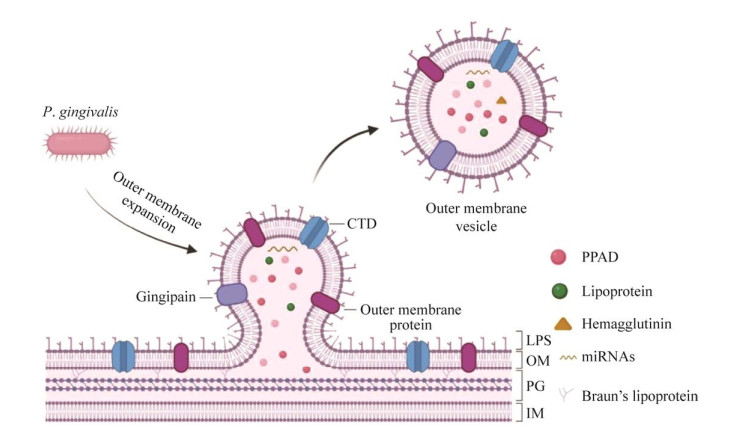

1 牙龈卟啉单胞菌外膜囊泡的发生和调控OMV的发生是一个需要消耗能量并受多种因素调节的过程(图 1)。首先,错误折叠或过度表达的包膜蛋白积累,使外膜的压力增加而形成凸起;然后,在外膜和肽聚糖间连接缺失的部位形成“出芽”;最后,囊泡“出芽”引起细菌外膜局部曲率增加[7-8]。OMV膜的曲率较细菌外膜高约14倍,而膜弯曲是一个能量密集型过程,从平坦膜形成球形囊泡的过程中,需要消耗约250–600 kBT的热能,因此,OMV的形成过程中还可能伴有OMV外膜上产生的特定脂质与特定蛋白质结合的过程,以降低OMV发生中的能量需求,通过不断的能量消耗以及特定脂质与蛋白质的富集,囊泡的曲率进一步显著增加,最终导致囊泡脱离细菌本体形成OMV[5, 8-9]。OMV的形成过程受菌毛蛋白A (fimbria protein A, FimA)基因型[10]、自溶素[11]、牙龈素[12]以及P. gingivalis肽基精氨酸脱亚氨酶(Porphyromonas gingivalis peptidylarginine deiminase, PPAD)[13]等的影响。fimA基因是P. gingivalis菌毛主要亚基菌毛素的编码基因,根据不同的fimA基因型,P. gingivalis菌株可分为I、Ib、II、III、IV和V等6种类型[14]。具有不同fimA基因型的菌株致病力有较大的差异,其中II和IV型与细菌的毒力增加有关[14],而Ⅰ、III和V型则代表低毒菌株[15]。Mantri等[10]通过对不同P. gingivalis菌株囊泡含量的研究发现,fimA突变体和无菌毛菌株W83,在标准培养条件下其生长培养基中囊泡产生量较ATCC 33277型菌株低约4–10倍,表明fimA基因的表达水平与OMV的产生效率呈正相关[10]。自溶素是一种内源性胞壁蛋白水解酶,可切割细胞壁肽聚糖中的共价键,参与细菌的生长、分裂和细胞壁重塑等过程,其生物活性与OMV的产生效率间呈负相关[11]。自溶素活性的降低可直接或间接导致细胞分泌OMV的增加[11]。牙龈素作为P. gingivalis的关键毒力因子,包括精氨酸特异性半胱氨酸蛋白酶(arginine gingipain, Rgp)和赖氨酸特异性半胱氨酸蛋白酶(lysine gingipain, Kgp),其中RgpA大多位于P. gingivalis外膜上,其活性的丧失可能会改变细菌表面性质,从而导致OMV产生的减少[12]。PPAD是一种蛋白质修饰酶,通过Ⅸ型分泌系统(type Ⅸ secretion system, T9SS)与许多毒力因子,包括许多具有保守C端结构域(C-terminal domain, CTD)的蛋白、LPS、血凝素等一起被分泌[16]。T9SS可将这些毒力因子输送至细菌外膜,并以OMV的形式释放到周围环境中[16]。PPAD可通过对T9SS分泌的其他蛋白质瓜氨酸化来调节P. gingivalis生物膜的形成,还可促进OMV的生物发生和释放,在缺乏PPAD的情况下,OMV的产生将显著减少[13, 17]。

|

| 图 1 牙龈卟啉单胞菌外膜囊泡的发生过程 Figure 1 The development of the outer membrane vesicles of Porphyromonas gingivalis. The outer membrane of P. gingivalis bulges under pressure and "sprouts" at the place where the connection between the outer membrane and peptidoglycan is missing, with the increase of the local curvature of the outer membrane, it eventually leads to the formation of OMV (created with BioRender.com, similarly hereinafter). Porphyromonas gingivalis外膜在压力下凸起,在外膜和肽聚糖间连接缺失的部位“出芽”,随着外膜局部曲率的增加,最终导致OMV的形成 |

|

|

OMV含有大量毒力因子,包括LPS、菌毛[10]、PPAD[16]、牙龈素和非编码小RNA (small RNA, sRNA)等[18-19],并且这些毒力因子成分并非一成不变,而是动态调整的,可根据不同的生长条件进行富集[20]。

Veith等[20]的研究发现,在血红素限制条件下,OMV中有20种蛋白质的丰度显著增加超过1.5倍,而在血红素过量条件下,则有29种蛋白质的丰度增加1.5倍以上;无论血红素限制还是过量的生长条件下,经胰蛋白酶消化的P. gingivalis W50裂解物中非OMP成分占主导,仅有5.6%和16%的蛋白位于细菌表面或外膜,然而,在OMV中,外膜相关蛋白则占OMV蛋白的98%,其中T9SS底物占60%,这反映了它们在OMV中的大量富集[20]。由T9SS分泌的蛋白与毒力相关[16],所以OMV可作为P. gingivalis毒力因子的重要载体,并经血液循环将其递送至远处的宿主器官发挥致病性[21]。然而,OMV发挥毒力的方式很大程度上依赖其含有的脂质、蛋白质与核酸[5]。脂质A作为LPS的核心结构,是LPS主要的内毒素和最具免疫活性的成分[22],除参与P. gingivalis W50选择性地将OMP分选入OMV的过程[23],其磷酸化状态还可能影响OMV外膜稳定性和OMV的潜在形成过程。OMV表面还有大量的CTD蛋白富集。许多CTD蛋白是强效毒力因子[24],其中大部分的CTD蛋白是牙龈素,牙龈素可被优先地包装在OMV中[25],而且P. gingivalis ATCC 33277和W83的OMV中牙龈素的水平分别是二者细胞表面提取物中牙龈素水平的3倍和5倍[10]。除了脂质和蛋白质成分外,OMV还含有一定数量的核酸,包括微小RNA (microRNA, miRNA)、长链RNA (long non-coding RNA, lncRNA)和环状RNA (circular RNA, circRNA)等非编码RNA[26]。其中一些miRNA大小的小RNA (microRNA-size small RNA, msRNA),可作为新的细菌信号分子介导细菌与宿主的相互作用[27]。另外,OMV中还含有部分DNA,可能在细菌间通讯、生物膜的形成和保护方面发挥重要的作用[28]。

3 牙龈卟啉单胞菌外膜囊泡与AD的相关性牙周炎过程中,OMV可经溃疡缺损的牙周袋内壁上皮侵入血流,由循环播散至远处的组织和器官[29],并可能透过血脑屏障(blood-brain barrier, BBB)触发核苷酸结合寡聚化结构域样受体蛋白3 (nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain-like receptor containing pyrin domain 3, NLRP3)炎症小体诱导神经炎症、tau蛋白磷酸化和记忆功能障碍,并在促进AD的发生、发展中起重要的作用[30-31]。

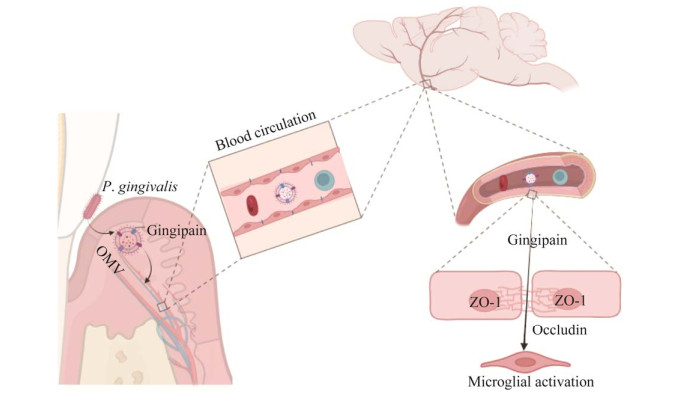

牙龈素作为OMV中的毒力因子之一,可能以OMV为载体被递送至脑微血管内皮细胞中,通过降解闭锁小带蛋白1 (zona occludens-1, ZO-1)和闭合蛋白(occludin)破坏BBB,最终进入大脑[30, 32] (图 2)。ZO-1是脑微血管内皮细胞紧密连接的辅助蛋白,可将occludin蛋白、连接黏附分子等连接起来,在紧密连接过程中发挥着重要的调控作用[33]。Occludin构成了紧密连接的主要部分,对维持BBB的完整性具有重要的意义。Pritchard等[34]通过将OMV作用于体外构建的人BBB的研究发现,OMV可通过破坏ZO-1和BBB的完整性而改变其通透性。另外,OMV经口服后可透过血脑屏障,并通过降低大脑中ZO-1、Occludin蛋白和相关基因的表达影响血脑屏障的功能[30]。进一步研究发现,P. gingivalis或OMV对BBB和其中关键成分ZO-1、occludin等的影响可能与牙龈素有关。Nonaka等[32]的研究发现,Kgp和Rgp协同诱导ZO-1的直接降解,而Kgp主要负责occludin的降解。ZO-1和occludin的降解增加了BBB的通透性[30, 32, 34],从而允许更多毒力因子进入大脑。Ilievski等[35]通过免疫组化、共聚焦显微镜和qPCR等技术方法发现小鼠海马区有P. gingivalis W83牙龈素的存在。最近,Dominy等[36]的研究还发现,与正常个体相比,AD患者大脑中的Kgp负荷明显增高。这些研究证实牙龈素可能以OMV为载体参与BBB通透性的改变和完整性的破坏,从而利于其侵入大脑。

|

| 图 2 牙龈素以外膜囊泡为载体透过血脑屏障的可能机制 Figure 2 Possible mechanism of gingivin passing through the blood-brain barrier with the outer membrane vesicles as carrier. Gingivin is delivered to brain microvascular endothelial cells through blood circulation using OMV as carrier, it increases BBB permeability by degrading ZO-1 and occludin tight junction protein, and activates microglia in brain through BBB. 牙龈素以OMV为载体,通过血液循环递送至脑微血管内皮细胞,通过降解ZO-1和occludin紧密连接蛋白,增加BBB通透性,透过BBB激活脑内小胶质细胞 |

|

|

小胶质细胞是中枢神经系统的常驻免疫细胞,普遍分布在大脑中,具有免疫监视、突触保护和重塑的功能。一些病理因素可促进小胶质细胞的激活,并使其迁移至病变部位,产生免疫应答[37]。牙龈素可通过诱导蛋白酶激活受体2 (protease activated receptor 2, PAR2)的Src激酶和β-arrestin依赖性内化,进一步激活激酶1/2 (extracellular signal regulated kinase1/2, ERK1/2)信号通路,以促进小胶质细胞的迁移和炎症反应[38-39]。Liu等[39]的研究则进一步证实,在使用牙龈素抑制剂后几乎完全抑制了P. gingivalis ATCC 33277感染诱导的小胶质细胞迁移和PAR2受体的激活。这表明牙龈素在激活PAR2受体、诱导小胶质细胞迁移过程中发挥了关键的作用。同时,牙龈素还在小胶质细胞介导的神经炎症和小鼠认知能力下降中起主要作用[40]。研究发现,通过抑制牙龈素不仅可抑制小胶质细胞的迁移,还可降低P. gingivalis ATCC 33277导致的脑部感染的负荷,阻断Aβ1-42产生,减轻神经炎症,并减轻海马体中神经元的损伤等[36, 39]。此外,近期研究发现,OMV经腹腔注射后,其牙龈素可在小鼠的脑室周围检测到,而且OMV可通过激活脑内小胶质细胞诱导神经炎症,最终导致AD样病理改变[41]。这些研究结果表明,作为富含牙龈素的OMV可能在AD的发病过程中发挥重要作用。

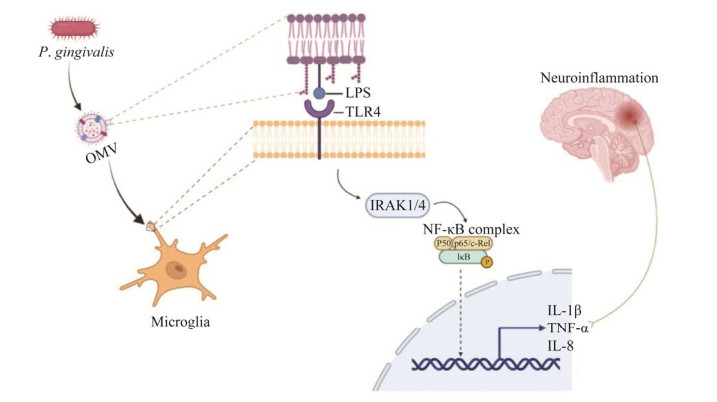

LPS作为OMV的关键毒力因子,可透过BBB进入AD患者的大脑[42]。不过,目前对LPS进入大脑的机制尚不清楚。推测LPS很可能是以OMV为载体,通过削弱BBB的完整性并增加其通透性来实现[34]。进入大脑的LPS可激活神经胶质细胞,诱导脑部炎症,并与β-淀粉样蛋白(amyloid β-protein, Aβ)沉积和神经原纤维缠结(neurofibrillary tangles, NFTs)的形成相关[31]。LPS诱发神经炎症,可能是通过与toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4)受体结合,激活白介素-1受体相关激酶1 (interleukin-1 receptor-associated kinase 1, IRAK1),最终激活下游的核转录因子-κB (nuclear factor-kappa B, NF-κB)信号通路,释放IL-1β、IL-6和TNF-α等炎性因子来实现[43]。Zhao等[44]的研究发现,使用TLR4抑制剂可抑制NF-κB信号通路的激活,并显著减轻由LPS诱导的神经炎症和认知功能障碍。因此,在LPS诱发神经炎症过程中,TLR4/NF-κB信号通路起着关键作用。OMV作为TLR4受体和NF-κB信号通路的有效激活剂,可诱导宿主免疫细胞产生IL-1β、TNF-α和IL-8等促炎因子[45]。由此推测OMV很可能在激活小胶质细胞、诱发神经炎症方面有相似的作用(图 3)。此外,Wei等[46]的研究从侧面进行了证实,其研究发现AD患者粪便OMV可经循环透过小鼠BBB激活小胶质细胞,并通过激活糖原合成酶激酶-3β (glycogen synthase kinase-3β, GSK-3β)途径诱导海马中tau蛋白过度磷酸化,并激活NF-κB信号通路诱导神经炎症反应,最终导致认知功能障碍。

|

| 图 3 外膜囊泡诱发神经炎症的可能机制 Figure 3 The possible mechanism of neuroinflammation induced by the outer membrane vesicles. LPS binds to TLR4 receptor, thus activating IRAK1 and then activating downstream NF-κB signal pathway, which releases inflammatory factors and ultimately induces neuroinflammation. LPS与TLR4受体结合,从而激活IRAK1进而激活下游的NF-κB信号通路,释放炎性因子,最终诱发神经炎症的过程 |

|

|

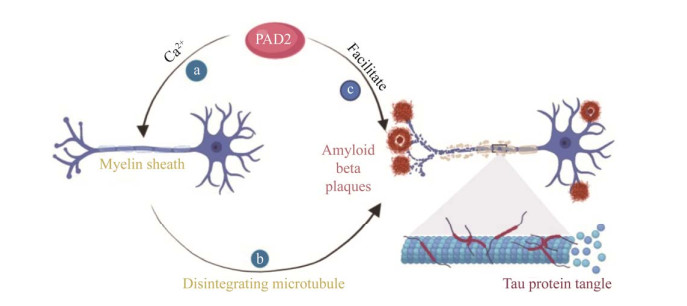

P. gingivalis可分泌大量PPAD,多数情况下PPAD富集在OMV中,少数情况下处于可溶性分泌状态[47]。PPAD作为一种特殊的毒力因子,可对宿主蛋白质和多肽中的精氨酸进行瓜氨酸化[48]。瓜氨酸化是一种生理和病理条件下均可发生的蛋白质翻译后修饰的过程。在病理条件下,蛋白质瓜氨酸化水平在炎症性疾病中明显升高,并与AD的发生直接相关[49]。人肽基精氨酸脱亚氨酶(peptidylarginine deiminase, PAD)是一类可介导修饰翻译后的蛋白质瓜氨酸化的钙依赖性半胱氨酸水解酶的家族,包括PAD1、PAD2、PAD3、PAD4和PAD6等5种类型,其中PAD2可介导中枢神经系统(central nervous system, CNS)中髓磷脂碱性蛋白(myelin basic protein, MBP)瓜氨酸化[50]。MBP通过与神经元质膜中的蛋白质结合,参与组成神经鞘膜并维持其稳定性,而瓜氨酸化的MBP破坏了质膜的结构,并使其容易受到蛋白水解酶的影响,增加了髓鞘的水解,最终导致CNS中髓鞘的紊乱[51]。正常情况下,PAD2处于相对不活跃状态,只有当Ca2+浓度显著升高时PAD2才介导瓜氨酸化过程[52]。大量证据表明Ca2+稳态的破坏与AD等神经退行性疾病的发展相关[53],Ca2+浓度升高可导致神经元凋亡和神经功能障碍。因此,PAD2是在AD的发生发展过程中被激活。被激活的PAD2还可介导胶质纤维酸性蛋白(glial fibrillary acidic protein, GFAP)的瓜氨酸化,GFAP是星形胶质细胞的主要结构蛋白,其瓜氨酸化水平与神经变性密切相关[54],并可在AD患者的海马中检测到瓜氨酸化的GFAP[55]。神经元细胞外Aβ纤维沉积是AD的主要病理特征之一。Mohlake等[56]的研究发现,PAD2不仅可与Aβ1‒40、Aβ22‒35、Aβ17‒28、Aβ25‒35和Aβ32‒35结合,还有助于这些多肽片段的蛋白水解和降解,同时形成不溶性纤维。通常情况下,淀粉样纤维既可通过淀粉样蛋白的组装过程形成,又可自我诱导,还可通过蛋白质分解机制形成。PAD2与多肽蛋白结合24 h即有不溶性纤维的形成,而且其形成速率与多肽蛋白的浓度呈正相关[56]。

Aβ25‒35具有神经毒性,本课题组前期研究证实,Aβ25‒35可经双侧侧脑室注射诱导AD的发生,而且Aβ1‒40和Aβ1‒42在AD模型鼠海马中异常沉积[57-58]。当将Aβ25‒35注射入大鼠侧脑室后,海马中瓜氨酸化的GFAP异常增加[59]。这些研究表明,PAD2在AD的发生、发展过程中起重要作用(图 4)。PPAD与PAD均可介导蛋白质和多肽中精氨酸的瓜氨酸化,但相较于后者,PPAD在介导蛋白质瓜氨酸化过程中具有明显优势。一方面,PPAD的活性与Ca2+浓度无关,即使在低Ca2+浓度的环境下也可有效地进行蛋白质修饰[60];另一方面,PPAD可与Rgp协同介导蛋白质的瓜氨酸化过程,Rgp通过切割蛋白质产生具有羧基末端的精氨酸残基片段,随后被PPAD瓜氨酸化[61],而且由PPAD介导的瓜氨酸化直接或间接地与AD相关[62]。

|

| 图 4 PAD2在阿尔茨海默病发生发展中的作用机制 Figure 4 The mechanism of PAD2 in the occurrence and development of Alzheimer's disease. a: During the development of AD, the concentration of Ca2+ increases and PAD2 is activated; b: PAD2 mediates citrullination of MBP and causes myelin collapse in CNS; c: PAD2 combines with polypeptide protein to promote the formation of insoluble fiber. a:AD发生发展过程中,Ca2+浓度升高,PAD2被激活;b:PAD2介导MBP瓜氨酸化,导致CNS中髓鞘崩解;c:PAD2与多肽蛋白结合,促进不溶性纤维的形成 |

|

|

OMV中含有一定数量的DNA片段,经PCR扩增发现,编码fimA和超氧化物歧化酶(superoxide dismutase, SOD)主要亚基的基因片段在OMV中含量较高,而且OMV中含有足够大的基因片段,如fimA基因包含启动子和终止子,表明OMV中DNA片段大到可以编码毒力因子[63]。Ho等[63]通过qPCR分析还发现,OMV中含有许多毒力因子包括fimA、RgpA和SOD等的mRNA。因此推测OMV中的核酸可能同样以OMV为载体参与P. gingivalis毒力因子信息的传递。目前,对OMV中核酸与AD相关性的研究较少。神经炎症在AD的发病机制中具有突出的作用[64]。最近研究发现[65-66],伴放线聚集杆菌(Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans) ATCC 33384的OMV可经循环透过血脑屏障,并将其胞内RNA递送至大脑,激活脑单核细胞或小胶质细胞,引发神经炎症。P. gingivalis与A. actinomycetemcomitans均属于革兰氏阴性菌,其OMV尺寸与A. actinomycetemcomitans-OMV相近[65],结构与之相似,很可能在AD的发病机制中具有类似的功能。

4 小结与展望大量研究证实感染和炎症尤其是牙周感染及炎症与AD发生、发展密切相关[67]。前期课题组研究证实,牙周炎可引发脑内神经炎症和AD的发生,并加重AD样病理改变[58, 68]。P. gingivalis是牙周炎症的关键致病菌,近来有研究表明P. gingivalis-OMV可能在AD的病理过程中发挥关键作用[6, 30-31, 41]。OMV作为P. gingivalis在生长过程中分泌的纳米级胞外囊泡,包含亲本细菌大量的毒力因子,可作为P. gingivalis毒力因子的重要载体逃避宿主免疫[3],经溃疡的牙周袋内壁上皮进入循环,并可透过血脑屏障[29],进而影响AD的发生、发展。然而OMV与AD的相关性尚待动物模型和临床研究进一步证实。目前对OMV诱导AD发生的研究较少,仅部分研究证实OMV中牙龈素可能通过降低紧密连接蛋白ZO-1和occludin的表达改变BBB的通透性[30, 32],而OMV中其他毒力因子如LPS、PPAD、菌毛及sRNA等可能参与AD特征性病理的具体作用及生物学机制尚不清楚。OMV发挥致病作用的关键成分,各种毒力因子在以OMV形式存在的条件下是相互协同从而发挥“1+1 > 2”的作用,抑或各毒力因子在疾病发展不同阶段、不同的特征性病理过程中各自作用,利用OMV或其致病毒力因子是否可能设计精准靶向抑制物从而预防或消除其可能影响等,诸多问题均有待进一步深入研究。截至目前,对P. gingivalis和AD的相关性研究大多集中在P. gingivalis或者其某个重要毒力因子,而P. gingivalis诱导AD的过程是各毒力因子共同作用的结果。因此,积极探索OMV及其包含的毒力因子在AD的发生、发展过程中的作用及机制,可望为进一步阐明牙周炎与AD的相关性提供理论参考,为AD的预防和治疗提供新的思路和靶点。

| [1] |

SCHELTENS P, de STROOPER B, KIVIPELTO M, HOLSTEGE H, CHÉTELAT G, TEUNISSEN CE, CUMMINGS J, van der FLIER WM. Alzheimer's disease[J]. The Lancet, 2021, 397(10284): 1577-1590. DOI:10.1016/S0140-6736(20)32205-4 |

| [2] |

XU WZ, ZHOU W, WANG HZ, LIANG S. Roles of Porphyromonas gingivalis and its virulence factors in periodontitis[J]. Advances in Protein Chemistry and Structural Biology, 2020, 120: 45-84. |

| [3] |

LUNAR SILVA I, CASCALES E. Molecular strategies underlying Porphyromonas gingivalis virulence[J]. Journal of Molecular Biology, 2021, 433(7): 166836. DOI:10.1016/j.jmb.2021.166836 |

| [4] |

BUI FQ, ALMEIDA-DA-SILVA CLC, HUYNH B, TRINH A, LIU J, WOODWARD J, ASADI H, OJCIUS DM. Association between periodontal pathogens and systemic disease[J]. Biomedical Journal, 2019, 42(1): 27-35. DOI:10.1016/j.bj.2018.12.001 |

| [5] |

GUI MJ, DASHPER SG, SLAKESKI N, CHEN YY, REYNOLDS EC. Spheres of influence: Porphyromonas gingivalis outer membrane vesicles[J]. Molecular Oral Microbiology, 2016, 31(5): 365-378. DOI:10.1111/omi.12134 |

| [6] |

ZHANG ZY, LIU DJ, LIU S, ZHANG SW, PAN YP. The role of Porphyromonas gingivalis outer membrane vesicles in periodontal disease and related systemic diseases[J]. Frontiers in Cellular and Infection Microbiology, 2020, 10: 585917. |

| [7] |

MCBROOM AJ, KUEHN MJ. Release of outer membrane vesicles by Gram-negative bacteria is a novel envelope stress response[J]. Molecular Microbiology, 2007, 63(2): 545-558. DOI:10.1111/j.1365-2958.2006.05522.x |

| [8] |

KULP A, KUEHN MJ. Biological functions and biogenesis of secreted bacterial outer membrane vesicles[J]. Annual Review of Microbiology, 2010, 64: 163-184. DOI:10.1146/annurev.micro.091208.073413 |

| [9] |

SCHERTZER JW, WHITELEY M. A bilayer-couple model of bacterial outer membrane vesicle biogenesis[J]. mBio, 2012, 3(2): e00297-e00211. |

| [10] |

MANTRI CK, CHEN CH, DONG XH, GOODWIN JS, PRATAP S, PAROMOV V, XIE H. Fimbriae-mediated outer membrane vesicle production and invasion of Porphyromonas gingivalis[J]. MicrobiologyOpen, 2015, 4(1): 53-65. DOI:10.1002/mbo3.221 |

| [11] |

HAYASHI JI, HAMADA N, KURAMITSU HK. The autolysin of Porphyromonas gingivalis is involved in outer membrane vesicle release[J]. FEMS Microbiology Letters, 2002, 216(2): 217-222. DOI:10.1111/j.1574-6968.2002.tb11438.x |

| [12] |

ZHANG R, YANG J, WU J, SUN WB, LIU Y. Effect of deletion of the rgpA gene on selected virulence of Porphyromonas gingivalis[J]. Journal of Dental Sciences, 2016, 11(3): 279-286. DOI:10.1016/j.jds.2016.03.004 |

| [13] |

VERMILYEA DM, KIM HM, DAVEY ME. PPAD activity promotes outer membrane vesicle biogenesis and surface translocation by Porphyromonas gingivalis[J]. Journal of Bacteriology, 2021, 203(4): e00343-e00320. |

| [14] |

NARA PL, SINDELAR D, PENN MS, POTEMPA J, GRIFFIN WST. Porphyromonas gingivalis outer membrane vesicles as the major driver of and explanation for neuropathogenesis, the cholinergic hypothesis, iron dyshomeostasis, and salivary lactoferrin in alzheimer's disease[J]. Journal of Alzheimer's Disease, 2021, 82(4): 1417-1450. DOI:10.3233/JAD-210448 |

| [15] |

KRISTOFFERSEN AK, SOLLI S J, NGUYEN TD, ENERSEN M. Association of the rgpB gingipain genotype to the major fimbriae (fimA) genotype in clinical isolates of the periodontal pathogen Porphyromonas gingivalis[J]. Journal of Oral Microbiology, 2015, 7: 29124. DOI:10.3402/jom.v7.29124 |

| [16] |

LASICA AM, KSIAZEK M, MADEJ M, POTEMPA J. The type IX secretion system (T9SS): highlights and recent insights into its structure and function[J]. Frontiers in Cellular and Infection Microbiology, 2017, 7: 215. DOI:10.3389/fcimb.2017.00215 |

| [17] |

VERMILYEA DM, OTTENBERG GK, DAVEY ME. Citrullination mediated by PPAD constrains biofilm formation in P. gingivalis strain 381[J]. Npj Biofilms and Microbiomes, 2019, 5: 7. DOI:10.1038/s41522-019-0081-x |

| [18] |

FARRUGIA C, STAFFORD GP, MURDOCH C. Porphyromonas gingivalis outer membrane vesicles increase vascular permeability[J]. Journal of Dental Research, 2020, 99(13): 1494-1501. DOI:10.1177/0022034520943187 |

| [19] |

DIALLO I, PROVOST P. RNA-sequencing analyses of small bacterial RNAs and their emergence as virulence factors in host-pathogen interactions[J]. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 2020, 21(5): 1627. DOI:10.3390/ijms21051627 |

| [20] |

VEITH PD, LUONG C, TAN KH, DASHPER SG, REYNOLDS EC. Outer membrane vesicle proteome of Porphyromonas gingivalis is differentially modulated relative to the outer membrane in response to heme availability[J]. Journal of Proteome Research, 2018, 17(7): 2377-2389. DOI:10.1021/acs.jproteome.8b00153 |

| [21] |

SEYAMA M, YOSHIDA K, YOSHIDA K, FUJIWARA N, ONO K, EGUCHI T, KAWAI H, GUO JJ, WENG Y, YUAN HZ, UCHIBE K, IKEGAME M, SASAKI A, NAGATSUKA H, OKAMOTO K, OKAMURA H, OZAKI K. Outer membrane vesicles of Porphyromonas gingivalis attenuate insulin sensitivity by delivering gingipains to the liver[J]. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA)-Molecular Basis of Disease, 2020, 1866(6): 165731. |

| [22] |

GAO J, GUO ZW. Progress in the synthesis and biological evaluation of lipid A and its derivatives[J]. Medicinal Research Reviews, 2018, 38(2): 556-601. DOI:10.1002/med.21447 |

| [23] |

RANGARAJAN M, ADUSE-OPOKU J, HASHIM A, MCPHAIL G, LUKLINSKA Z, HAURAT MF, FELDMAN MF, CURTIS MA. LptO (PG0027) is required for lipid A 1-phosphatase activity in Porphyromonas gingivalis W50[J]. Journal of Bacteriology, 2017, 199(11): e00751-e00716. |

| [24] |

BRAUN ML, TOMEK MB, GRÜNWALD-GRUBER C, NGUYEN PQ, BLOCH S, POTEMPA JS, ANDRUKHOV O, SCHÄFFER C. Shut-down of type IX protein secretion alters the host immune response to Tannerella forsythia and Porphyromonas gingivalis[J]. Frontiers in Cellular and Infection Microbiology, 2022, 12: 835509. DOI:10.3389/fcimb.2022.835509 |

| [25] |

HAURAT MF, ADUSE-OPOKU J, RANGARAJAN M, DOROBANTU L, GRAY MR, CURTIS MA, FELDMAN MF. Selective sorting of cargo proteins into bacterial membrane vesicles[J]. Journal of Biological Chemistry, 2011, 286(2): 1269-1276. DOI:10.1074/jbc.M110.185744 |

| [26] |

CHEW CL, CONOS SA, UNAL B, TERGAONKAR V. Noncoding RNAs: master regulators of inflammatory signaling[J]. Trends in Molecular Medicine, 2018, 24(1): 66-84. DOI:10.1016/j.molmed.2017.11.003 |

| [27] |

CHOI JW, KIM SC, HONG SH, LEE HJ. Secretable small RNAs via outer membrane vesicles in periodontal pathogens[J]. Journal of Dental Research, 2017, 96(4): 458-466. DOI:10.1177/0022034516685071 |

| [28] |

BITTO NJ, CHAPMAN R, PIDOT S, COSTIN A, LO C, CHOI J, D'CRUZE T, REYNOLDS EC, DASHPER SG, TURNBULL L, WHITCHURCH CB, STINEAR TP, STACEY KJ, FERRERO RL. Bacterial membrane vesicles transport their DNA cargo into host cells[J]. Scientific Reports, 2017, 7: 7072. DOI:10.1038/s41598-017-07288-4 |

| [29] |

AGUAYO S, SCHUH CMAP, VICENTE B, AGUAYO LG. Association between alzheimer's disease and oral and gut microbiota: are pore forming proteins the missing link?[J]. Journal of Alzheimer's Disease: JAD, 2018, 65(1): 29-46. DOI:10.3233/JAD-180319 |

| [30] |

GONG T, CHEN Q, MAO HC, ZHANG Y, REN H, XU MM, CHEN H, YANG DQ. Outer membrane vesicles of Porphyromonas gingivalis trigger NLRP3 inflammasome and induce neuroinflammation, tau phosphorylation, and memory dysfunction in mice[J]. Frontiers in Cellular and Infection Microbiology, 2022, 12: 925435. DOI:10.3389/fcimb.2022.925435 |

| [31] |

SINGHRAO SK, OLSEN I. Are Porphyromonas gingivalis outer membrane vesicles microbullets for sporadic alzheimer's disease manifestation?[J]. Journal of Alzheimer's Disease Reports, 2018, 2(1): 219-228. DOI:10.3233/ADR-180080 |

| [32] |

NONAKA S, KADOWAKI T, NAKANISHI H. Secreted gingipains from Porphyromonas gingivalis increase permeability in human cerebral microvascular endothelial cells through intracellular degradation of tight junction proteins[J]. Neurochemistry International, 2022, 154: 105282. DOI:10.1016/j.neuint.2022.105282 |

| [33] |

ABBOTT NJ, PATABENDIGE AA, DOLMAN DE, YUSOF SR, BEGLEY DJ. Structure and function of the blood-brain barrier[J]. Neurobiology of disease, 2010, 37(1): 13-25. DOI:10.1016/j.nbd.2009.07.030 |

| [34] |

PRITCHARD AB, FABIAN Z, LAWRENCE CL, MORTON G, CREAN S, ALDER JE. An investigation into the effects of outer membrane vesicles and lipopolysaccharide of Porphyromonas gingivalis on blood-brain barrier integrity, permeability, and disruption of scaffolding proteins in a human in vitro model[J]. Journal of Alzheimer's Disease, 2022, 86(1): 343-364. DOI:10.3233/JAD-215054 |

| [35] |

ILIEVSKI V, ZUCHOWSKA PK, GREEN SJ, TOTH PT, RAGOZZINO ME, LE K, ALJEWARI HW, O'BRIEN-SIMPSON NM, REYNOLDS EC, WATANABE K. Chronic oral application of a periodontal pathogen results in brain inflammation, neurodegeneration and amyloid beta production in wild type mice[J]. PLoS One, 2018, 13(10): e0204941. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0204941 |

| [36] |

DOMINY SS, LYNCH C, ERMINI F, BENEDYK M, MARCZYK A, KONRADI A, NGUYEN M, HADITSCH U, RAHA D, GRIFFIN C, HOLSINGER LJ, ARASTU-KAPUR S, KABA S, LEE A, RYDER MI, POTEMPA B, MYDEL P, HELLVARD A, ADAMOWICZ K, et al. Porphyromonas gingivalis in Alzheimer's disease brains: evidence for disease causation and treatment with small-molecule inhibitors[J]. Science Advances, 2019, 5(1): eaau3333. DOI:10.1126/sciadv.aau3333 |

| [37] |

HENEKA MT, CARSON MJ, EL KHOURY J, LANDRETH GE, BROSSERON F, FEINSTEIN DL, JACOBS AH, WYSS-CORAY T, VITORICA J, RANSOHOFF RM, HERRUP K, FRAUTSCHY SA, FINSEN B, BROWN GC, VERKHRATSKY A, YAMANAKA K, KOISTINAHO J, LATZ E, HALLE A, PETZOLD GC, et al. Neuroinflammation in Alzheimer's disease[J]. The Lancet Neurology, 2015, 14(4): 388-405. DOI:10.1016/S1474-4422(15)70016-5 |

| [38] |

NONAKA S, NAKANISHI H. Secreted gingipains from Porphyromonas gingivalis induce microglia migration through endosomal signaling by protease-activated receptor 2[J]. Neurochemistry International, 2020, 140: 104840. DOI:10.1016/j.neuint.2020.104840 |

| [39] |

LIU YC, WU Z, NAKANISHI Y, NI JJ, HAYASHI Y, TAKAYAMA F, ZHOU YM, KADOWAKI T, NAKANISHI H. Author Correction: infection of microglia with Porphyromonas gingivalis promotes cell migration and an inflammatory response through the gingipain-mediated activation of protease-activated receptor-2 in mice[J]. Scientific Reports, 2018, 8: 10304. DOI:10.1038/s41598-018-27508-9 |

| [40] |

NAKANISHI H, NONAKA S, WU Z. Microglial cathepsin B and Porphyromonas gingivalis gingipains as potential therapeutic targets for sporadic alzheimer's disease[J]. CNS & Neurological Disorders Drug Targets, 2020, 19(7): 495-502. |

| [41] |

YOSHIDA K, YOSHIDA K, SEYAMA M, HIROSHIMA Y, MEKATA M, FUJIWARA N, KUDO Y, OZAKI K. Porphyromonas gingivalis outer membrane vesicles in cerebral ventricles activate microglia in mice[J]. Oral Diseases, 2022. DOI:10.1111/odi.14413 |

| [42] |

POOLE S, SINGHRAO SK, KESAVALU L, CURTIS MA, CREAN S. Determining the presence of periodontopathic virulence factors in short-term postmortem Alzheimer's disease brain tissue[J]. Journal of Alzheimer's Disease: JAD, 2013, 36(4): 665-677. DOI:10.3233/JAD-121918 |

| [43] |

ZHANG J, YU CB, ZHANG X, CHEN HW, DONG JC, LU WL, SONG ZC, ZHOU W. Porphyromonas gingivalis lipopolysaccharide induces cognitive dysfunction, mediated by neuronal inflammation via activation of the TLR4 signaling pathway in C57BL/6 mice[J]. Journal of Neuroinflammation, 2018, 15(1): 37. DOI:10.1186/s12974-017-1052-x |

| [44] |

ZHAO JY, BI W, XIAO S, LAN X, CHENG XF, ZHANG JW, LU DX, WEI W, WANG YP, LI HM, FU YM, ZHU LH. Neuroinflammation induced by lipopolysaccharide causes cognitive impairment in mice[J]. Scientific Reports, 2019, 9: 5790. DOI:10.1038/s41598-019-42286-8 |

| [45] |

CECIL JD, O'BRIEN-SIMPSON NM, LENZO JC, HOLDEN JA, SINGLETON W, PEREZ-GONZALEZ A, MANSELL A, REYNOLDS EC. Outer membrane vesicles prime and activate macrophage inflammasomes and cytokine secretion in vitro and in vivo[J]. Frontiers in Immunology, 2017, 8: 1017. DOI:10.3389/fimmu.2017.01017 |

| [46] |

WEI SC, PENG WJ, MAI YR, LI KL, WEI W, HU L, ZHU SP, ZHOU HH, JIE WX, WEI ZS, KANG CY, LI RK, LIU Z, ZHAO B, CAI ZY. Outer membrane vesicles enhance tau phosphorylation and contribute to cognitive impairment[J]. Journal of Cellular Physiology, 2020, 235(5): 4843-4855. DOI:10.1002/jcp.29362 |

| [47] |

GABARRINI G, PALMA MEDINA LM, STOBERNACK T, PRINS RC, du TEIL ESPINA M, KUIPERS J, CHLEBOWICZ MA, ROSSEN JWA, van WINKELHOFF AJ, van DIJL JM. There's no place like OM: vesicular sorting and secretion of the peptidylarginine deiminase of Porphyromonas gingivalis[J]. Virulence, 2018, 9(1): 459-467. DOI:10.1080/21505594.2017.1421827 |

| [48] |

BIELECKA E, SCAVENIUS C, KANTYKA T, JUSKO M, MIZGALSKA D, SZMIGIELSKI B, POTEMPA B, ENGHILD JJ, PROSSNITZ ER, BLOM AM, POTEMPA J. Peptidyl arginine deiminase from Porphyromonas gingivalis abolishes anaphylatoxin C5a activity[J]. Journal of Biological Chemistry, 2014, 289(47): 32481-32487. DOI:10.1074/jbc.C114.617142 |

| [49] |

BAKA Z, GYÖRGY B, GÉHER P, BUZÁS EI, FALUS A, NAGY G. Citrullination under physiological and pathological conditions[J]. Joint Bone Spine, 2012, 79(5): 431-436. DOI:10.1016/j.jbspin.2012.01.008 |

| [50] |

JANG B, JEON YC, SHIN HY, LEE YJ, KIM H, KONDO Y, ISHIGAMI A, KIM YS, CHOI EK. Myelin basic protein citrullination, a hallmark of central nervous system demyelination, assessed by novel monoclonal antibodies in prion diseases[J]. Molecular Neurobiology, 2018, 55(4): 3172-3184. DOI:10.1007/s12035-017-0560-0 |

| [51] |

WANG L, CHEN HY, TANG J, GUO ZW, WANG YM. Peptidylarginine deiminase and alzheimer's disease[J]. Journal of Alzheimer's Disease: JAD, 2022, 85(2): 473-484. DOI:10.3233/JAD-215302 |

| [52] |

ZHENG L, NAGAR M, MAURAIS AJ, SLADE DJ, PARELKAR SS, COONROD SA, WEERAPANA E, THOMPSON PR. Calcium regulates the nuclear localization of protein arginine deiminase 2[J]. Biochemistry, 2019, 58(27): 3042-3056. DOI:10.1021/acs.biochem.9b00225 |

| [53] |

BERRIDGE MJ. Dysregulation of neural calcium signaling in Alzheimer disease, bipolar disorder and schizophrenia[J]. Prion, 2013, 7(1): 2-13. DOI:10.4161/pri.21767 |

| [54] |

YUSUF IO, QIAO T, PARSI S, TILVAWALA R, THOMPSON PR, XU ZS. Protein citrullination marks myelin protein aggregation and disease progression in mouse ALS models[J]. Acta Neuropathologica Communications, 2022, 10(1): 1-22. DOI:10.1186/s40478-021-01305-4 |

| [55] |

ISHIGAMI A, MASUTOMI H, HANDA S, NAKAMURA M, NAKAYA S, UCHIDA Y, SAITO Y, MURAYAMA S, JANG B, JEON YC, CHOI EK, KIM YS, KASAHARA Y, MARUYAMA N, TODA T. Mass spectrometric identification of citrullination sites and immunohistochemical detection of citrullinated glial fibrillary acidic protein in Alzheimer's disease brains[J]. Journal of Neuroscience Research, 2015, 93(11): 1664-1674. |

| [56] |

MOHLAKE P, WHITELEY CG. Arginine metabolising enzymes as therapeutic tools for alzheimer's disease: peptidyl arginine deiminase catalyses fibrillogenesis of β-amyloid peptides[J]. Molecular Neurobiology, 2010, 41(2): 149-158. |

| [57] |

WANG Q, HUANG L, LI X, GE S. Effects of experimental periodontitis on intestinal morphology and cognitive ability of rats[J]. Journal of Zunyi Medical University, 2022, 45(2): 139-146. (in Chinese) 王琴, 黄兰, 李霞, 葛颂. 实验性牙周炎对大鼠肠屏障功能及认知能力的影响[J]. 遵义医科大学学报, 2022, 45(2): 139-146. |

| [58] |

ZHANG S, YANG FC, WANG ZZ, QIAN XS, JI Y, GONG L, GE S, YAN FH. Poor oral health conditions and cognitive decline: studies in humans and rats[J]. PLoS One, 2020, 15(7): e0234659. |

| [59] |

ARIF M, KATO T. Increased expression of PAD2 after repeated intracerebroventricular infusions of soluble Aβ25-35 in the Alzheimer's disease model rat brain: effect of memantine[J]. Cellular and Molecular Biology Letters, 2009, 14(4): 703-714. |

| [60] |

MARESZ KJ, HELLVARD A, SROKA A, ADAMOWICZ K, BIELECKA E, KOZIEL J, GAWRON K, MIZGALSKA D, MARCINSKA KA, BENEDYK M, PYRC K, QUIRKE AM, JONSSON R, ALZABIN S, VENABLES PJ, NGUYEN KA, MYDEL P, POTEMPA J. Porphyromonas gingivalis facilitates the development and progression of destructive arthritis through its unique bacterial peptidylarginine deiminase (PAD)[J]. PLoS Pathogens, 2013, 9(9): e1003627. |

| [61] |

WEGNER N, WAIT R, SROKA A, EICK S, NGUYEN KA, LUNDBERG K, KINLOCH A, CULSHAW S, POTEMPA J, VENABLES PJ. Peptidylarginine deiminase from Porphyromonas gingivalis citrullinates human fibrinogen and α-enolase: implications for autoimmunity in rheumatoid arthritis[J]. Arthritis and Rheumatism, 2010, 62(9): 2662-2672. |

| [62] |

OLSEN I, SINGHRAO SK, POTEMPA J. Citrullination as a plausible link to periodontitis, rheumatoid arthritis, atherosclerosis and Alzheimer's disease[J]. Journal of Oral Microbiology, 2018, 10(1): 1487742. |

| [63] |

HO MH, CHEN CH, GOODWIN JS, WANG BY, XIE H. Functional advantages of Porphyromonas gingivalis vesicles[J]. PLoS One, 2015, 10(4): e0123448. |

| [64] |

LENG FD, EDISON P. Neuroinflammation and microglial activation in Alzheimer disease: where do we go from here?[J]. Nature Reviews Neurology, 2021, 17(3): 157-172. |

| [65] |

HAN EC, CHOI SY, LEE Y, PARK JW, HONG SH, LEE HJ. Extracellular RNAs in periodontopathogenic outer membrane vesicles promote TNF-α production in human macrophages and cross the blood-brain barrier in mice[J]. FASEB Journal: Official Publication of the Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology, 2019, 33(12): 13412-13422. |

| [66] |

HA JY, CHOI SY, LEE JH, HONG SH, LEE HJ. Delivery of periodontopathogenic extracellular vesicles to brain monocytes and microglial IL-6 promotion by RNA cargo[J]. Frontiers in Molecular Biosciences, 2020, 7: 596366. |

| [67] |

LICCARDO D, MARZANO F, CARRATURO F, GUIDA M, FEMMINELLA GD, BENCIVENGA L, AGRIMI J, ADDONIZIO A, MELINO I, VALLETTA A, RENGO C, FERRARA N, RENGO G, CANNAVO A. Potential bidirectional relationship between periodontitis and alzheimer's disease[J]. Frontiers in Physiology, 2020, 11: 683. |

| [68] |

QIAN XS, ZHANG S, DUAN L, YANG FC, ZHANG K, YAN FH, GE S. Periodontitis deteriorates cognitive function and impairs neurons and Glia in a mouse model of alzheimer's disease[J]. Journal of Alzheimer's Disease: JAD, 2021, 79(4): 1785-1800. |

2023, Vol. 50

2023, Vol. 50