扩展功能

文章信息

- 赵皓静, 王晓丹, 邱树毅, 曾超, 章钰浛, 崔东琦, 黄武, 班世栋

- ZHAO Haojing, WANG Xiaodan, QIU Shuyi, ZENG Chao, ZHANG Yuhan, CUI Dongqi, HUANG Wu, BAN Shidong

- 液质发酵食品中微生物群落及与乳酸菌间相互作用研究进展

- Microbial community and interaction between lactic acid bacteria and microorganisms in liquid fermented food: a review

- 微生物学通报, 2021, 48(3): 960-973

- Microbiology China, 2021, 48(3): 960-973

- DOI: 10.13344/j.microbiol.china.200483

-

文章历史

- 收稿日期: 2020-05-17

- 接受日期: 2020-09-07

- 网络首发日期: 2020-11-10

2. 贵州大学贵州省发酵工程与生物制药重点实验室 贵州 贵阳 550025;

3. 西安瑞联新材料股份有限公司 陕西 西安 710003

2. Key Laboratory of Fermentation Engineering and Bio-Pharmacy of Guizhou Province, Guizhou University, Guiyang, Guizhou 550025, China;

3. Xi'an Ruilian New Materials Company Limited, Xi'an, Shaanxi 710003, China

液质发酵食品是一类呈液体状态发酵食品的统称,主要包括食醋、酱油等液体调味品以及白酒、葡萄酒等饮料酒等[1]。其传统的酿造环境开放度高,通常采用自然接种的固态或半固态发酵工艺,或者部分原料不经灭菌处理直接使用生料[2]。因此,在粗放的酿造环境中,复杂多样的微生物以原料为基质,将原料中的淀粉、脂肪和蛋白质等大分子物质分解、转化成相应的小分子物质供自身生长代谢,发酵过程中微生物群落结构不断演替,促使发酵连续进行[3-4]。在微生物群落演替中,微生物之间的相互作用十分复杂,影响着乳酸菌和其他微生物的结构组成和发酵过程中化合物的组成与变化。

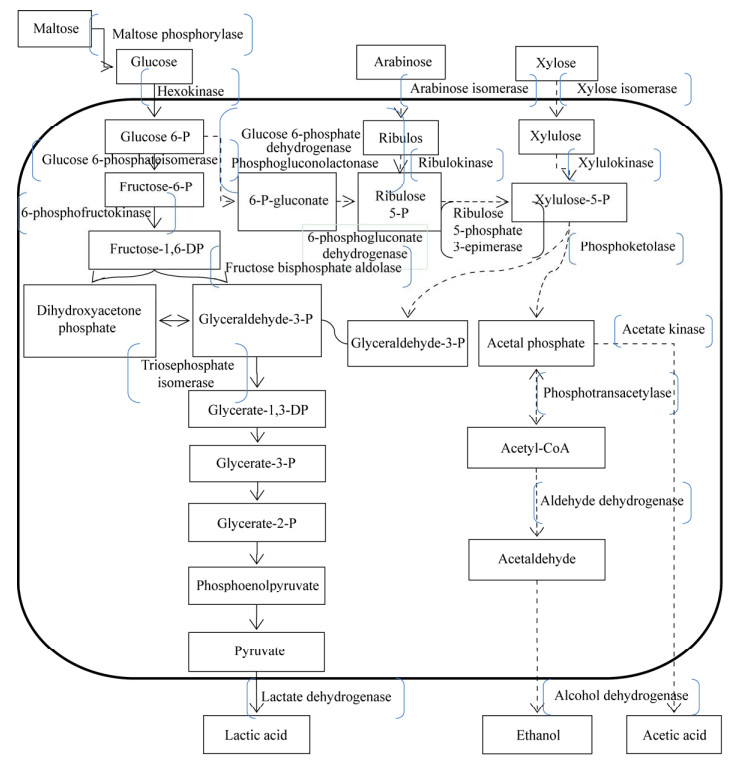

乳酸菌是酿造食品自然发酵中重要的功能菌,是一类利用碳水化合物代谢主要产生乳酸的革兰氏阳性细菌的统称,广泛存在于液质发酵食品体系中。乳杆菌属(Lactobacillus)、魏斯氏菌属(Weissella)和片球菌属(Pediococcus)是液质发酵食品在发酵过程中的主要乳酸菌群[5-6]。乳酸菌具有营养和益生功能,能代谢原料的化学成分,有益于消化吸收、改善风味和口感及提高营养价值[7];能产生各种醛类、酯类、醇类和酮类等低阈值挥发性化合物,增加食品风味[8];能拮抗杂菌、降解有害物质,提高食品安全性并延长保藏期[9-10];能降低胆固醇、抗肿瘤、提高免疫力、预防衰老及缓解乳糖不耐症等[11]。乳酸菌在发酵过程中主要产乳酸,有2条乳酸代谢途径(图 1)[12-13]:(1) 同型乳酸发酵途径。以葡萄糖为底物通过糖酵解途径(Embden-Meyerhof Pathway,EMP)降解为丙酮酸,然后在乳酸脱氢酶催化下还原生成乳酸。(2) 异型乳酸发酵途径。葡萄糖经戊糖磷酸途径(Hexose Monophosphate Pathway,HMP)发酵后除主要产生乳酸外,还产生乙醇、乙酸和CO2等多种代谢产物,赋予发酵食品特有的口味和香味[14]。此外,乳酸菌也能产生一些类似细菌素等拮抗性代谢产物,对其他乳酸菌、食物腐败菌和食源性致病菌具有广泛的抑制作用[15]。Cizeikiene等[16]实验发现乳酸菌的代谢产物不同程度地抑制了小麦面包中芽孢杆菌(Bacillus)、假单胞菌(Pseudomonas)、李斯特菌(Listeria)和大肠杆菌属(Escherichia genera)等致病菌的生长。

|

| 图 1 乳酸菌乳酸代谢途径 Figure 1 Metabolic pathway for lactic acid of lactic acid bacteria |

|

|

本文对液质发酵食品微生物群落结构及群落中乳酸菌与其他微生物间的相互作用进行综述,探讨乳酸菌在液质发酵食品发酵过程中的功能和作用机制。

1 液质发酵食品中微生物群落多样性及演替规律食品发酵需要多种微生物菌群协调作用完成,微生物利用发酵原料中的营养物质可以自发地富集,通过与微生物和发酵环境间的相互作用,长期驯化逐步形成一个持续变化又相对稳定的微生物群落结构[17]。同时群落中微生物也会随着发酵工艺、营养基质和发酵环境的变化而对自身进行调控[18]。研究发现,发酵微生物群落具有微生物种类繁多、功能多样、微生物间相互作用复杂的基本特征[19]。

液质发酵食品(食醋、酱油、饮料酒等)是传统发酵食品的重要组成部分[3],在其发酵体系中微生物种类多样(表 1)。

| 液质发酵食品 Liquid fermented food |

主要微生物 Main microorganisms |

参考文献 References |

| 酱油 Soy sauce |

Mold: Aspergillus Yeast: Zygosaccharomyces rouxii, Toruiopsis, Candida Bacteria: Bacillus, Staphylococcus, Micrococcus, Lactobacillus, Tetragenococcus |

[20-21] |

| 食醋 Vinegar |

Mold: Aspergillus, Rhizopus, Paecilomyces, Mucor Yeast: Saccharomyces cerevisiae, Pichia anomala Bacteria: Lactobacillus, Acetobacter |

[22] |

| 白酒 Baijiu |

Mold: Rhizopus, Paecilomyces, Aspergillus, Mucor Yeast: Saccharomyces cerevisiae, Zygosaccharomyces bailii, Schizosaccharomyces pombe Bacteria: Lactobacillus, Weissella, Pediococcus, Bacillus, Clostridium Archaea: Methanobrevibacter, Methanobacterium |

[23] |

| 黄酒 Huangjiu |

Mold: Aspergillus, Rhizopus Yeast: Saccharomyces, Candida, Cryptococcus Bacteria: Bacillus, Lactobacillus |

[24-25] |

| 葡萄酒 Wine |

Yeast: Saccharomyces, Pichia, Candida, Hanseniaspora, Schizosaccharomyces, Dekkera, Metschnikowia, Issatchenkia, Saccharomycodes, Zygosaccharomyces Bacteria: Oenococcus, Latobacillus, Leuconostoc, Pediococcus |

[26] |

对传统发酵食品微生物结构的深入研究,有助于阐明发酵食品微生物间的相互作用方式和机理,认清微生物菌群代谢功能,提高产率,改善传统发酵食品风味和保障发酵食品安全。近年来,对发酵食品中微生物菌群的种类、丰度及其演替规律研究较多。Yang等[27]在发酵豆豉中分离出20个细菌属,其中,葡萄球菌属(Staphylococcus)和魏斯氏菌属(Weissella)为优势属;观察葡萄球菌属和魏斯氏菌属丰度变化趋势,发现2个菌种之间存在种间竞争。Edalati等[28]发现魏斯氏菌属代谢产生有机酸和细菌素会抑制葡萄球菌属的生长。张娇娇等[29]研究红曲米醋制曲的4个阶段的微生物,发现子囊菌门在丰度上一直占优势且大致呈先降后增的趋势;受曲中营养物质、pH和乙醇等影响,在不同制曲时期优势属会发生改变。微生物群落在发生演替时会伴随着微生物功能性的转变。Song等[30]分析了酱香型白酒发酵体系中酵母属和乳酸菌属的微生物丙酮酸代谢途径,结果表明丙酮酸在酵母和乳酸菌中分为2个阶段代谢产生风味成分,揭示酱香型白酒在不同发酵阶段裂殖酵母属(Schizosaccharomyce)与乳酸杆菌属(Lactobacillus)会进行功能性转换,促使风味成分由醇类向酸类转化。

2 液质发酵食品群落中乳酸菌与其他微生物间相互作用 2.1 发酵过程中微生物间相互作用液质发酵食品中,微生物间相互作用不仅影响了自身的功能特性,还改变了整个发酵体系内微生物的种类构成和功能[31]。微生物相互作用的机理知识可以更好地调控发酵过程的参数,优化食品发酵过程的控制,最终有利于发酵食品品质和安全性的稳定与提高[32]。

2.1.1 发酵过程中微生物间相互作用的类型微生物是一种结构简单的有机体,但却具有社会属性。在食品发酵过程中,微生物不仅与发酵环境存在复杂的感应反馈关系,而且不同微生物个体间也有着较为复杂的作用关系。这些复杂的微生物间相互作用关系可能是正相关作用、负相关作用或者是无影响等。微生物间的相互作用关系复杂多样,根据微生物作用方式可大致分为通过直接接触的直接相互作用,以及通过引起环境物理化学性质发生变化而触发其他微生物反应的间接相互作用[33]。多数研究中将微生物间的相互作用主要分为5种类型:互利共生(+/+)、偏利共生(+/0)、寄生(+/−)、偏害共生(−/0)、竞争(−/−)[33-34],如表 2所示。

| 相互作用类型 Type of interaction |

定义 Definition |

举例 Examples |

参考文献 References |

| 互利共生 Mutualistic symbiosis |

不同微生物在共生的过程中均从对方受益 Different organisms benefit from each other in the process of symbiosis |

Stadie等研究水开菲尔酵母菌和乳酸菌之间的协同作用,发现在水开菲尔培养基中酵母和乳酸菌的共培养显著提高了两种菌群数量 Stadie et al. studied the synergistic effects of water kefir yeasts and lactobacilli and found that co-cultivation of yeasts and lactobacilli in water kefir medium significantly increased cell yield of all interaction partners |

[35] |

| 偏利共生 Commensalistic symbiosis |

两种微生物在共生时,一种微生物从二者的相互作用中受益,而另一微生物不受影响 In symbiosis, one microbe benefits from the interaction, while the other is unaffected |

乳酪发酵中嗜热链球菌为保加利亚乳杆菌提供自身不能合成的氨基酸、甲酸、叶酸以及吡啶等物质 During cheese fermentation, Streptococcus thermophilus provides Lactobacillus bulgaricus with non-synthetic amino acids, formic acid, folic acid and pyridine |

[36-37] |

| 寄生 Parasitism |

两种微生物共生时,一种微生物受益,而另一种微生物受害,后者为前者提供生长所需营养物质及生存空间 When two organisms live symbiotically, one benefits and the other suffers, providing nutrients and space for the former to grow |

噬菌体通过感染乳酸菌寄生于乳酸菌中,乳酸菌噬菌体会破坏乳制品生产中发酵剂的天然能力,是工业乳制品生产中的一大威胁 The bacteriophage parasitizes the lactic acid bacteria through the infection of lactic acid bacteria. The bacteriophage of lactic acid bacteria will destroy the natural ability of the starter in the production of dairy products |

[38] |

| 偏害共生 Amensalistic symbiosis |

两种微生物共生时,一种微生物对另一微生物有害,而自身不受影响 When two organisms live in symbiosis, one is harmful to the other without affecting itself |

乳酸乳球菌产生的尼生素可抑制李斯特菌或其他乳酸菌的生长 Niacin produced by Lactococcus lactis can inhibit the growth of Listeria or other lactic acid bacteria |

[39] |

| 竞争 Competition |

两种微生物在同一环境中,对营养物质、溶氧、空间和其他要求的物质相互竞争,相互受到不利影响 The two microorganisms compete and are adversely affected by each other in the same environment for nutrients, dissolved oxygen, space and other required substances |

在一些食品的发酵过程中,如奶酪中微生物相互争夺氮源和红酒中微生物相互争夺硫胺素等 In the fermentation process of some foods, for example, microorganisms in cheese compete for nitrogen sources, and microorganisms in red wine compete for thiamine |

[40] |

除了上述微生物之间存在的相互作用类型,微生物在群体水平上会产生群体感应(Quorum sensing,QS)实现微生物细胞与细胞之间的交流。通过化学信号的积累,感知附近种群密度和物种复杂性的变化,然后协调集体行为[41],即群体中的微生物通过群体感应系统传递信息,形成种内或种间相互作用。Almeida等[42]在可可豆自然发酵的细菌菌群中发现存在预想的群体感应现象,发现表明群体感应能在发酵的不同时间点调节细菌数量,以维持长时间内细菌的丰度优势。

2.1.2 发酵食品中微生物间相互作用的机制通过传统的共培养实验和当前的组学技术,可以在快速判定发酵体系中微生物间相互作用类型的基础上,更深入地认识群体微生物间复杂的相互作用机制[31]。在食品发酵体系中,微生物与其周围的其他微生物之间存在着多种多样的相互作用关系来影响彼此的生长和代谢。根据目前国内外微生物间相互作用的研究结果,发酵食品中微生物间相互作用机制有以下几种:

(1) 营养竞争机制

乳酸菌与其他微生物间的相互作用可归因于对营养物质的非特异性竞争。这些营养物质是发酵体系中微生物生长所需要的,乳酸菌与其他微生物之间争夺环境中自身需要的营养物质来扩大菌群数量。优势菌群会消耗其他微生物菌群用于生长的基质,从而抑制它们的生长。当生长环境中营养物质全部耗尽,这场营养竞争随之结束,所有微生物在其中的生长也会停止。Mellefont等[43]研究表明,利用Saccharomyces cerevisiae和Metschnikowia pulcherrima或Hanseniaspora vinae进行的混合共发酵,发现微生物间存在明显的营养竞争。

(2) 代谢产物作用机制

发酵微生物在生产过程中能代谢产生一些分泌物,通过这些代谢产物对发酵体系中其他微生物产生协同或拮抗作用。研究表明,乳酸菌与酵母菌之间存在着代谢产物互补机制,Rosa等[44]总结了开菲尔酒中微生物复杂的共生关系,在这种关系中酵母菌产生维生素、氨基酸和其他对细菌很重要的基本生长因子。同样,细菌的代谢产物也被用作酵母的能量来源。Adesulu-Dahunsi等[45]综述了乳酸菌和酵母之间的相互协同作用,指出发酵食品中酵母菌的生长受到乳酸菌代谢乳酸所造成的酸化环境的促进,酵母菌可以为乳酸菌提供生长因子,如维生素和可溶性氮化合物,所以酵母菌的存在也刺激了乳酸菌的生长。与协同作用相反,在发酵过程中乳酸菌和酵母菌也能通过代谢产生一些拮抗类分泌物,相互间产生拮抗作用。在乳酸菌和酵母菌混合培养体系中,乳酸菌的生长会受到溶脂酵母代谢生成的脂肪酸的影响,而乳酸菌的代谢产物乳酸、4-羟基-苯乳酸、环肽会抑制酵母菌的生长[46]。

(3) 信号分子形成机制

在发酵过程中微生物菌群会产生一种在群体水平上的相互作用——群体感应。乳酸菌群体感应系统通过感知细胞密度来调节特定的基因表达[47],最终调控乳酸菌多种重要的生理功能,如调控乳酸菌生物膜的形成[48]、酸胁迫应答[49]、抗菌肽和胞外酶的合成[50-51]。微生物自身会分泌被称为信号分子的胞外小分子,信号分子可以穿出和进入细胞,并在环境中积累。随着微生物菌体密度的增大,信号分子在环境中的浓度也增加,当这些信号分子在微生物生长环境中积累到一定的浓度,并且在细胞内的积累也超过一定的阈值时,就会被特异受体识别,启动某些特定基因的表达,相关的蛋白合成上升,因此形成了种内或种间的相互作用,达到对自身或其他微生物的协同或抑制作用[52]。目前报道中,乳酸菌的信号分子有AIPII、LamD、PltA、IP-TX、PlnA和IP-673等[53],酵母菌的信号分子一般为芳香醇类和萜烯类,如法尼醇、酪醇、色醇和苯乙醇[49]。

(4) 发酵环境胁迫机制

食品发酵过程中发酵微生物会受到乙醇浓度、pH、温度和渗透压等发酵环境的胁迫,并导致生长速度和存活率的下降[54]。在酒精发酵阶段,酵母菌的代谢产物乙醇会对同一发酵环境中的乳酸菌产生乙醇胁迫,乙醇使细胞膜的流动性增加,导致辅因子的泄漏和膜电位的损失;不仅如此,乙醇也使膜内蛋白质和细胞质变性,对乳酸菌新陈代谢产生不利影响,抑制其生长[55]。乳酸菌则通过代谢产生乳酸等有机酸扰动环境pH,造成酸胁迫[56]。pH会影响发酵环境中营养物质的解离、微生物细胞膜的生理功能及通透性[57-58],致使发酵过程中微生物对营养物质的吸收和代谢物分泌能力降低,以及细胞内对酸敏感的代谢关键酶和DNA等生物大分子受损[59],最终使环境中微生物的生长代谢受抑制。Deng等[60]研究苦毕赤酵母和酿酒酵母对乳酸胁迫的协同响应中发现,乳酸可以穿透细胞膜,通过简单扩散进入细胞质,然后水解释放出质子和乳酸离子,这些离子不能穿过细胞膜,因此在细胞内积累,使细胞内pH发生改变和破坏细胞质阴离子池,影响嘌呤碱基的完整性,导致细胞中关键酶发生变性,从而抑制白酒发酵过程中酵母菌的生长代谢。发酵体系中各种微生物的生长代谢物逐渐积累形成的高渗环境会对乳酸菌和其他微生物造成盐胁迫,引起胞内水分外流,细胞缩水使得细胞膜结构受损,无法维持正常的细胞形态,最终造成发酵环境中微生物的失活[61]。

2.2 食醋中乳酸菌与其他微生物 2.2.1 乳酸菌对食醋发酵的影响食醋主要有以谷物为原料多菌固态或液态混合酿造的谷物醋,如中国四大名醋山西老陈醋、镇江香醋、福建永春老醋和四川保宁麸醋,以及日本的米醋、西方国家的麦芽醋等,还有以水果为主要原料经纯种液态深层发酵所得的果醋[62]。食醋发酵过程中微生物相互作用,各种微生物提供了大量的酶来合成风味和功能物质,如有机酸、氨基酸和挥发性成分等,影响食醋的风味和功能[63]。发酵体系中,酵母菌将可发酵糖厌氧转化为乙醇,然后由醋酸菌将乙醇氧化生成醋酸[64],而乳酸菌代谢产生适量的乳酸来平衡醋酸,柔和食醋酸感,同时也丰富了食醋的风味成分[65]。李岩等[66]研究表明,巴氏醋杆菌、瑞士乳杆菌和干酪乳杆菌在接种量为3.0%、5.0%和5.0%的发酵条件下获得的葡萄醋品质最好;混合微生物发酵会产生醋酸、苹果酸、乳酸、柠檬酸等多种有机酸,赋予葡萄醋丰富的口感。

2.2.2 食醋发酵微生物群落中乳酸菌与其他微生物间的相互作用食醋发酵主要是以酵母菌和曲霉这些真菌为主、以乳酸菌和醋酸菌为优势的细菌相互协同作用的过程[67],但食醋酿造微生物间的共生作用会受体系中营养物质和氧气的影响。乳酸菌的生长通常需要氨基酸、不饱和脂肪酸和维生素等各种营养物质,共生时酵母菌和曲霉可以为乳酸菌提供其所需要的营养物质;乳酸菌和酵母菌为厌氧菌,但曲霉和醋酸菌必须在有氧环境中才能生长,因此曲霉和醋酸菌在生长过程中可以消耗共生体系中的氧气,为乳酸菌提供有利的生长环境[68]。由此可看出,在食醋酿造中酵母菌、曲霉和醋酸菌的存在可以促进乳酸菌的生长繁殖。食醋发酵通常都有酒精发酵和醋酸发酵2个阶段[69],在醋酸发酵阶段,好氧微生物会在发酵液表面的有氧环境中形成生物膜,产生一个有利于乳酸菌和酵母菌生长的无氧环境[68]。Furukawa等[68, 70]发现,从福山壶食醋酿造样品中分离出的L. plantarum ML11-11和Saccharomyces cerevisiae通过细胞与细胞之间直接接触,它们在静态共培养中形成了一个混合菌种生物膜,同时,研究还发现酿造样品中分离出的巴氏醋酸杆菌与乳酸菌菌株混合培养后都形成了生物膜,并且生物膜的形成还受乳酸的诱导。牟俊[18]研究发现,在山西老陈醋醋酸发酵阶段醋酸菌与乳酸菌共生中,醋酸菌代谢生成的高浓度乙酸可以抑制乳酸菌的糖代谢等途径,从而对其生长和代谢产生很强的抑制作用。然而乳酸菌的代谢产物利于醋酸菌与细胞呼吸和能量代谢相关的硫代谢途径,促进醋酸菌的生长繁殖。

2.3 酱油中乳酸菌与其他微生物 2.3.1 乳酸菌对酱油发酵的影响酱油酿造是微生物产生各种酶分解原料中的营养物质来生长繁殖的一个过程。各种微生物相互作用,为酱油的色、香、味、体做出贡献[71]。在酱醪发酵阶段,主要的微生物群落为耐盐的乳酸菌和酵母菌,乳酸菌产生乳酸,降低了环境中的pH值,较低的pH值为嗜酸酵母菌,如鲁式接合酵母、假丝酵母、球拟酵母提供了一个合适的生长环境[72],这些酵母菌又能通过产生乙醇和挥发性风味化合物提高酱油的质量[73]。Guo等[74]研究皮脂葡萄球菌(Staphylococcus piscifermentans)和耐盐酵母共生发酵酱油,结果表明共接种后微生物相互作用使Zygosaccharomyces和Pichia丰度增加,Pediococcus、Weissella和Streptococcus等细菌减少,最终使得生物胺产量降低及醇类、醛类、酚类和酯类等挥发性化合物增加,提高了高氨基酸氮酱油的品质。

2.3.2 酱油发酵微生物群落中乳酸菌与其他微生物间的相互作用酱油在酿造过程中形成了一个由真菌、酵母菌和细菌组成的复杂的微生物群落,酱油酿造有两步发酵过程,即固态发酵和盐水发酵[75]。其中,细菌主要是乳酸菌(如魏斯氏菌和嗜盐四联球菌)、芽孢杆菌和葡萄球菌,真菌主要包括酵母菌(如鲁氏接合酵母和假丝酵母)、米曲霉等[76]。嗜盐四联球菌(T. halophilus)和鲁氏接合酵母(Z. rouxii)在酱油盐水发酵阶段微生物中占主导地位[77]。多种微生物在酱油发酵过程中共存时,会发生互惠互利、竞争和拮抗等复杂的相互作用。

在盐水发酵开始阶段,发酵体系中pH值在6.0−7.0左右,具有相对较高的酸碱度,这种pH环境有利于T. halophilus的生长。但T. halophilus的生长繁殖导致有机酸的产生和酱醪酸化,当pH值降至5.0以下时,T. halophilus的生长会受到抑制,但却适合Z. rouxii的生长和代谢[75]。酱油发酵中乳酸菌对其他微生物间的抑制作用可通过产生抑制物的作用机制来介导,魏斯氏菌通过核糖体合成机制产生一类具有抑菌活性的多肽或前体多肽(如Ⅱ型细菌素),抑制腐败微生物和致病菌的生长[78]。Noda等[79-80]证明T. halophilus嗜盐乳杆菌产生的乙酸和乳酸能够抑制Z. rouxii和易变球拟酵母(Torulopsis versatilis)的生长,还提出在相同的pH值下,乙酸比乳酸具有更高的抑制活性,而且随着pH值的降低抑制活性显著增高。此外,Kusumegi等[81]的一项研究表明,乙酸可以通过抑制Z. rouxii R-1的呼吸活性和细胞色素的形成来抑制其生长。

2.4 饮料酒中乳酸菌与其他微生物 2.4.1 乳酸菌对饮料酒发酵的影响在我国现行的饮料酒分类标准GB/T 17204-2008[82]中,将饮料酒定义为酒精度在0.5% (体积分数)以上的酒精饮料,主要包括3类:发酵酒、蒸馏酒和配制酒。饮料酒的生产都会涉及以粮谷、水果、乳类等作为原料经多种微生物群落联合进行复杂发酵的过程,微生物的相互作用对饮料酒的成分、风味和质量都有深远的影响[83]。Liu等[84]在研究微生物对黑莓酒发酵动力和感官性能的影响中发现,黑莓酒发酵过程中酿酒酵母能将糖类转化为酒精并调节一些其他的代谢物,许多非酵母菌种与酵母相互作用使黑莓酒的成分和感官特性发生改变。

2.4.2 饮料酒发酵微生物群落中乳酸菌与其他微生物间的相互作用酵母菌与乳酸菌共生时,酿酒酵母代谢产物如乙醇、脂肪酸、抗菌肽和嗜杀毒素等会对其他酵母菌和细菌产生抑制作用[85]。乙醇影响细胞膜的通透性,通过诱导细胞膜渗透来灭活细菌,所以大多数微生物不能耐受高浓度的乙醇[86]。5% (体积比)的乙醇可以增加细胞膜的通透性,增加质子进入细胞质中,使细菌细胞无法维持pH值的稳定,从而提高了对较低pH值的敏感性,抑制一些乳酸菌的生长[87]。脂肪酸有助于葡萄酒香气和风味的形成,但含有10−12碳原子的游离中链脂肪酸对乳酸菌有害,游离脂肪酸分子进入乳酸菌细胞后,解离释放出H+,从而改变乳酸菌跨膜质子梯度[88]。Branco等[89]研究抗菌肽对葡萄酒发酵微生物的生理变化,研究表明,这些抗菌肽破坏了季也蒙有孢汉逊酵母(H. guilliermondii)细胞质膜的完整性,扰乱了其细胞内pH的稳态并导致可培养性的丧失。此外,啤酒中酿酒酵母与乳酸菌也会产生竞争作用,也会使乳酸菌的生长繁殖受到抑制。Sakamoto等[90]曾发现在碳水化合物和氨基酸等营养物质浓度非常低的发酵环境中,酿酒酵母会比其他细菌或酵母菌更先消耗环境中的营养物质。

饮料酒发酵体系中乳酸菌为优势的细菌分类,可以通过产生有机酸、竞争营养物质、产生抗菌素等途径抑制其他微生物的生长[91]。刘彩霞等[92]以高产酯酿酒酵母和3种同型发酵乳酸菌为研究对象,结果表明乳酸菌对高产酯酿酒酵母的生长和代谢有明显的抑制作用,研究认为是由于乳酸菌与高产酯酿酒酵母共同竞争发酵液中的营养成分,而且乳酸菌的代谢产物乳酸改变了发酵环境,导致了酿酒酵母的数量减少;同时,一部分乳杆菌与酿酒酵母所带电荷不同发生凝聚,促使部分酵母菌凝聚沉结在底部,减弱了酵母菌的发酵作用,也使其代谢物产量降低;乳酸菌能利用葡萄糖进行乳酸发酵,产生乳酸和乙酸等有机酸、H2O2、细菌素等多种具有天然抑菌活性的代谢产物,会抑制其他微生物生长繁殖。其中,乳酸、乙酸等有机酸和CO2会降低发酵环境中的pH值,较低的pH值会导致细胞酸化、破坏酶系统和降低营养吸收[93],从而抑制大多数微生物的生长。罗青春等[94]对酿酒酵母、毕赤酵母、布氏乳杆菌和耐酸乳杆菌进行纯培养和共培养对比研究发现,2株乳酸菌代谢合成乳酸使环境中pH值下降,抑制了毕赤酵母的生长和乙醇代谢。对于乳酸菌分泌细菌素抑制微生物生长方面,舒梨等[95]从浓香型窖泥中以双层琼脂扩散法筛选出了一株具有高抑菌活性的副干酪乳杆菌株LP16,其代谢分泌的细菌素对大肠杆菌、枯草芽孢杆菌以及部分乳酸菌有明显的抑制作用。

乳酸菌与一些酿造微生物共生时也会促进相互的生长繁殖和代谢。闫彬等[96]发现对酵母泥中大分子物质乙醇提取后再添加到合成培养基上,使得乳酸菌的迟滞期缩短、数量增加;与此同时,酿酒酵母分泌的蛋白酶,可以有效地分解蛋白质,生成氨基酸等生长因子,弥补乳杆菌只能通过代谢乳糖进行生长而造成繁殖速度缓慢的缺陷。张艳等[97]研究酱香型白酒发酵中2株主要乳酸菌对酿造微生物的影响,发现乳酸菌通过分泌乳酸形成弱酸性培养环境,促进了酵母菌的生长。Sieuwerts等[98]研究啤酒中乳杆菌与酵母菌共发酵过程及之后的酿造过程,发现酿酒酵母在发酵过程中可分泌各种营养因子如氨基酸、维生素等,促进了乳杆菌的生长;同时,通过对氧气的消耗在液体内部形成局部的厌氧环境,在发酵后期酵母菌也进行无氧呼吸生成CO2,阻碍了外界环境中的氧气进入发酵液,为乳杆菌提供良好的生长条件,促进乳酸菌生长繁殖。Shou等[99]对2株营养缺陷型酿酒酵母共培养,根据生长代谢情况发现二者呈互利共生关系,相互为对方提供生长所需要的氨基酸。

3 展望微生物是液质发酵食品的发酵动力,乳酸菌群是发酵微生物群落中的重要组成部分。在发酵过程中,乳酸菌不是孤立存在的,它与其他微生物间会发生各种不同的相互作用,推动着整体发酵微生物群落结构和功能的改变,影响着液质发酵食品最终风味的形成、营养物质的生成、口感的改善、安全性的提升等。截至目前,对食醋、酱油和白酒酿造过程中乳酸菌与其他微生物共生的研究逐渐增多,在共生中乳酸菌通过代谢分泌乳酸来影响自身或其他微生物生长的现象普遍存在,但乳酸对乳酸菌或其他微生物的作用机理需要进一步研究。随着现阶段分子生物技术和宏组学技术的发展,为更深入地了解乳酸菌与其他微生物间的相互作用提供了技术支持。本文综述了液质发酵食品中微生物群落及与乳酸菌间相互作用的研究进展,以期为进一步了解和研究白酒中乳杆菌酸胁迫应答机制奠定基础。

| [1] |

Xie HD. The research on ultraviolet spectral characteristics of liquid fermented food and the establishment of the technology system of authenticity identification[D]. Yangling: Doctoral Dissertation of Northwest A & F University, 2010(in Chinese) 解华东. 液质发酵食品紫外光谱特性研究及鉴真技术体系建立[D]. 杨凌: 西北农林科技大学博士学位论文, 2010 |

| [2] |

Lu ZM, Liu N, Wang LJ, Wu LH, Gong JS, Yu YJ, Li GQ, Shi JS, Xu ZH. Elucidating and regulating the acetoin production role of microbial functional groups in multispecies acetic acid fermentation[J]. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 2016, 82(19): 5860-5868. DOI:10.1128/AEM.01331-16 |

| [3] |

Ren C, Du H, Xu Y. Advances in microbiome study of traditional Chinese fermented foods[J]. Acta Microbiologica Sinica, 2017, 57(6): 885-898. (in Chinese) 任聪, 杜海, 徐岩. 中国传统发酵食品微生物组研究进展[J]. 微生物学报, 2017, 57(6): 885-898. |

| [4] |

Zhang XJ, Lu ZM, Chai LJ, Shi JS, Xu ZH. Research strategies for microbial ecology of traditional Chinese fermented foods[J]. Scientia Sinica Vitae, 2019, 49(5): 575-584. (in Chinese) 张晓娟, 陆震鸣, 柴丽娟, 史劲松, 许正宏. 中国传统酿造食品微生物生态学及其研究策略[J]. 中国科学: 生命科学, 2019, 49(5): 575-584. |

| [5] |

Jiao JK, Zhang LW, Yi HX. Isolation and characterization of lactic acid bacteria from fresh Chinese traditional rice wines using denaturing gradient gel electrophoresis[J]. Food Science and Biotechnology, 2016, 25(1): 173-178. DOI:10.1007/s10068-016-0026-6 |

| [6] |

Zou W, Zhao CQ, Luo HB. Diversity and function of microbial community in Chinese strong-flavor baijiu ecosystem: a review[J]. Frontiers in Microbiology, 2018, 9: 671. DOI:10.3389/fmicb.2018.00671 |

| [7] |

Jampaphaeng K, Ferrocino I, Giordano M, Rantsiou K, Maneerat S, Cocolin L. Microbiota dynamics and volatilome profile during stink bean fermentation (Sataw-Dong) with Lactobacillus plantarum KJ03 as a starter culture[J]. Food Microbiology, 2018, 76: 91-102. DOI:10.1016/j.fm.2018.04.012 |

| [8] |

Geng DH, Liang TT, Yang M, Wang LL, Zhou XR, Sun XB, Liu L, Zhou SM, Tong LT. Effects of Lactobacillus combined with semidry flour milling on the quality and flavor of fermented rice noodles[J]. Food Research International, 2019, 126: 108612. DOI:10.1016/j.foodres.2019.108612 |

| [9] |

Licandro H, Ho PH, Nguyen TKC, Petchkongkaew A, Van Nguyen H, Chu-Ky S, Nguyen TVA, Lorn D, Waché Y. How fermentation by lactic acid bacteria can address safety issues in legumes food products?[J]. Food Control, 2020, 110: 106957. DOI:10.1016/j.foodcont.2019.106957 |

| [10] |

Duan XX, Duan S, Wang QE, Ji R, Cao Y, Miao JY. Effects of the natural antimicrobial substance from Lactobacillus paracasei FX-6 on shelf life and microbial composition in chicken breast during refrigerated storage[J]. Food Control, 2020, 109: 106906. DOI:10.1016/j.foodcont.2019.106906 |

| [11] |

Yin LB, Zhou J, He P, Liao C, Yang AL, Liu D, Li LC. Preparation of peptide from soybean processing waste water by lactic acid bacteria fermentation and its antioxidant activity in vitro[J]. Food and Fermentation Industries, 2020, 46(11): 131-137. (in Chinese) 尹乐斌, 周娟, 何平, 廖聪, 杨爱莲, 刘丹, 李立才. 乳酸菌发酵豆清液制备多肽及其体外抗氧化活性研究[J]. 食品与发酵工业, 2020, 46(11): 131-137. |

| [12] |

Abdel-Rahman MA, Tashiro Y, Sonomoto K. Recent advances in lactic acid production by microbial fermentation processes[J]. Biotechnology Advances, 2013, 31(6): 877-902. DOI:10.1016/j.biotechadv.2013.04.002 |

| [13] |

Zhang YX, Zeng F, Hohn K, Vadlani PV. Metabolic flux analysis of carbon balance in Lactobacillus strains[J]. Biotechnology Progress, 2016, 32(6): 1397-1403. DOI:10.1002/btpr.2361 |

| [14] |

Miao LH, Bai FL, Li JR. Advanced on ecological succession of lactic acid bacteria in traditional fermented food[J]. Food and Fermentation Industries, 2015, 41(1): 175-180. (in Chinese) 缪璐欢, 白凤翎, 励建荣. 传统发酵食品中乳酸菌生态演替研究进展[J]. 食品与发酵工业, 2015, 41(1): 175-180. |

| [15] |

Xi QW, Wang J, Du RP, Zhao FK, Han Y, Zhou ZJ. Purification and characterization of bacteriocin produced by a strain of Enterococcus faecalis TG2[J]. Aplied Biochemistry and Biotechnology, 2018, 184(4): 1106-1119. DOI:10.1007/s12010-017-2614-1 |

| [16] |

Cizeikiene D, Juodeikiene G, Paskevicius A, Bartkiene E. Antimicrobial activity of lactic acid bacteria against pathogenic and spoilage microorganism isolated from food and their control in wheat bread[J]. Food Control, 2013, 31(2): 539-545. DOI:10.1016/j.foodcont.2012.12.004 |

| [17] |

Xie WC, Yin C, Song L, Xu ZY, Yu WL, Jia JT, Zhao HW, Zhang JY, Li YJ, Yang XH. Research progress of microorganism and its metabolism in traditional fermentation food[J]. Food and Fermentation Industries, 2018, 44(10): 253-259. (in Chinese) 解万翠, 尹超, 宋琳, 许志颖, 于文露, 贾俊涛, 赵宏伟, 张俊逸, 李钰金, 杨锡洪. 中国传统发酵食品微生物多样性及其代谢研究进展[J]. 食品与发酵工业, 2018, 44(10): 253-259. |

| [18] |

Mou J. Interaction between lactic acid bacteria and acetic acid bacteria in the acetic acid fermentation process of Shanxi aged vinegar[D]. Tianjin: Master's Thesis of Tianjin University of Science and Technology, 2018(in Chinese) 牟俊. 山西老陈醋醋酸发酵阶段乳酸菌和醋酸菌相互作用研究[D]. 天津: 天津科技大学硕士学位论文, 2018 |

| [19] |

Wang HL, Zhou WC, Ren C, Xu Y. Recent advances in the study of microbes in traditional fermented foods[J]. Journal of Biology, 2018, 35(6): 1-5. (in Chinese) 王慧琳, 周炜城, 任聪, 徐岩. 传统发酵食品微生物学研究进展[J]. 生物学杂志, 2018, 35(6): 1-5. |

| [20] |

Sulaiman J, Gan HM, Yin WF, Chan KG. Microbial succession and the functional potential during the fermentation of Chinese soy sauce brine[J]. Frontiers in Microbiology, 2014, 5: 556. |

| [21] |

Yang Y, Deng Y, Jin YL, Liu YX, Xia BX, Sun Q. Dynamics of microbial community during the extremely long-term fermentation process of a traditional soy sauce[J]. Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture, 2017, 97(10): 3220-3227. DOI:10.1002/jsfa.8169 |

| [22] |

Wang ZM, Lu ZM, Shi JS, Xu ZH. Exploring flavour-producing core microbiota in multispecies solid-state fermentation of traditional Chinese vinegar[J]. Scientific Reports, 2016, 6: 26818. DOI:10.1038/srep26818 |

| [23] |

Wang XS, Du H, Xu Y. Source tracking of prokaryotic communities in fermented grain of Chinese strong-flavor liquor[J]. International Journal of Food Microbiology, 2017, 244: 27-35. DOI:10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2016.12.018 |

| [24] |

Hong XT, Chen J, Liu L, Wu H, Tan HQ, Xie GF, Xu Q, Zou HJ, Yu WJ, Wang L, et al. Metagenomic sequencing reveals the relationship between microbiota composition and quality of Chinese Rice Wine[J]. Scientific Reports, 2016, 6: 26621. DOI:10.1038/srep26621 |

| [25] |

Liu YY. Characterization of microflora and their functions on flavor compounds in Shaoxing rice wine[D]. Wuxi: Master's Thesis of Jiangnan University, 2015(in Chinese) 刘芸雅. 绍兴黄酒发酵中微生物群落结构及其对风味物质影响研究[D]. 无锡: 江南大学硕士学位论文, 2015 |

| [26] |

Liu YZ, Rousseaux S, Tourdot-Maréchal R, Sadoudi M, Gougeon R, Schmitt-Kopplin P, Alexandre H. Wine microbiome: a dynamic world of microbial interactions[J]. Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition, 2017, 57(4): 856-873. DOI:10.1080/10408398.2014.983591 |

| [27] |

Yang L, Yang HL, Tu ZC, Wang XL. High-throughput sequencing of microbial community diversity and dynamics during Douchi fermentation[J]. PLoS One, 2016, 11(12): e0168166. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0168166 |

| [28] |

Edalati E, Saneei B, Alizadeh M, Hosseini SS, Bialvaei AZ, Taheri K. Isolation of probiotic bacteria from raw camel's milk and their antagonistic effects on two bacteria causing food poisoning[J]. New Microbes and New Infections, 2019, 27: 64-68. DOI:10.1016/j.nmni.2018.11.008 |

| [29] |

Zhang JJ, Li J, Fan BQ, Du P, Zheng Y, Zhu LL, Song J. Microbial community succession during koji making process of red koji rice vinegar and its effects on biochemical indexes[J]. China Brewing, 2019, 38(12): 36-42. (in Chinese) 张娇娇, 李婧, 范冰倩, 杜鹏, 郑宇, 朱立磊, 宋佳. 红曲米醋制曲过程中微生物群落演替及其对生化指标的影响[J]. 中国酿造, 2019, 38(12): 36-42. |

| [30] |

Song ZW, Du H, Zhang Y, Xu Y. Unraveling core functional microbiota in traditional solid-state fermentation by high-throughput amplicons and metatranscriptomics sequencing[J]. Frontiers in Microbiology, 2017, 8: 1294. DOI:10.3389/fmicb.2017.01294 |

| [31] |

Meng X. Interactions between Saccharomyces cerevisiae and Bacillus licheniformis isolated from Maotai flavor liquor fermentation and their mechanisms[D]. Wuxi: Master's Thesis of Jiangnan University, 2015(in Chinese) 孟醒. 酱香型白酒酿造来源的酿酒酵母与地衣芽孢杆菌相互作用特征及机制的初步解析[D]. 无锡: 江南大学硕士学位论文, 2015 |

| [32] |

Smid EJ, Lacroix C. Microbe-microbe interactions in mixed culture food fermentations[J]. Current Opinion in Biotechnology, 2013, 24(2): 148-154. DOI:10.1016/j.copbio.2012.11.007 |

| [33] |

Olanbiwoninu AA, Odunfa SA. Microbial interaction in selected fermented vegetable condiments in Nigeria[J]. International Food Research Journal, 2018, 25(1): 439-445. |

| [34] |

Winters M, Arneborg N, Appels R, Howell K. Can community-based signalling behaviour in Saccharomyces cerevisiae be called quorum sensing? A critical review of the literature[J]. FEMS Yeast Research, 2019, 19(5): foz046. DOI:10.1093/femsyr/foz046 |

| [35] |

Stadie J, Gulitz A, Ehrmann MA, Vogel RF. Metabolic activity and symbiotic interactions of lactic acid bacteria and yeasts isolated from water kefir[J]. Food Microbiology, 2013, 35(2): 92-98. DOI:10.1016/j.fm.2013.03.009 |

| [36] |

Wang T, Xu ZS, Lu SY, Xin M, Kong J. Effects of glutathione on acid stress resistance and symbiosis between Streptococcus thermophilus and Lactobacillus delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus[J]. International Dairy Journal, 2016, 61: 22-28. DOI:10.1016/j.idairyj.2016.03.012 |

| [37] |

Kort R, Westerik N, Serrano LM, Douillard FP, Gottstein W, Mukisa IM, Tuijn CJ, Basten L, Hafkamp B, Meijer WC, et al. A novel consortium of Lactobacillus rhamnosus and Streptococcus thermophilus for increased access to functional fermented foods[J]. Microbial Cell Factories, 2015, 14: 195. DOI:10.1186/s12934-015-0370-x |

| [38] |

Połaska M, Sokołowska B. Bacteriophages: a new hope or a huge problem in the food industry[J]. AIMS Microbiology, 2019, 5(4): 324-346. DOI:10.3934/microbiol.2019.4.324 |

| [39] |

Ivey M, Masse M, Phister TG. Microbial interactions in food fermentations[J]. Annual Review of Food Science and Technology, 2013, 4(1): 141-162. DOI:10.1146/annurev-food-022811-101219 |

| [40] |

Sieuwerts S, Molenaar D, Van Hijum SAFT, Beerthuyzen M, Stevens MJA, Janssen PWM, Ingham CJ, De Bok FAM, De Vos WM, Van Hylckama Vlieg JET. Mixed-culture transcriptome analysis reveals the molecular basis of mixed-culture growth in Streptococcus thermophilus and Lactobacillus bulgaricus[J]. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 2010, 76(23): 7775-7784. DOI:10.1128/AEM.01122-10 |

| [41] |

Hawver LA, Jung SA, Ng WL. Specificity and complexity in bacterial quorum-sensing systems[J]. FEMS Microbiology Reviews, 2016, 40(5): 738-752. DOI:10.1093/femsre/fuw014 |

| [42] |

Almeida OGG, Pinto UM, Matos CB, Frazilio DA, Braga VF, Von Zeska-Kress MR, De Martinis ECP. Does Quorum Sensing play a role in microbial shifts along spontaneous fermentation of cocoa beans? An in silico perspective[J]. Food Research International, 2020, 131: 109034. DOI:10.1016/j.foodres.2020.109034 |

| [43] |

Mellefont LA, Mcmeekin TA, Ross T. Effect of relative inoculum concentration on Listeria monocytogenes growth in co-culture[J]. International Journal of Food Microbiology, 2008, 121(2): 157-168. DOI:10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2007.10.010 |

| [44] |

Rosa DD, Dias MMS, Grześkowiak ŁM, Reis SA, Conceição LL, Peluzio MDCG. Milk kefir: nutritional, microbiological and health benefits[J]. Nutrition Research Reviews, 2017, 30(1): 82-96. DOI:10.1017/S0954422416000275 |

| [45] |

Adesulu-Dahunsi AT, Dahunsi SO, Olayanju A. Synergistic microbial interactions between lactic acid bacteria and yeasts during production of Nigerian indigenous fermented foods and beverages[J]. Food Control, 2020, 110: 106963. DOI:10.1016/j.foodcont.2019.106963 |

| [46] |

Yao SJ, Jin Y, Zhou RQ, Wu CD. Interaction and its application of microorganisms in traditional fermented food[J]. Biotechnology & Business, 2019(4): 48-54. (in Chinese) 姚尚杰, 金垚, 周荣清, 吴重德. 传统发酵食品中微生物间相互作用及应用[J]. 生物产业技术, 2019(4): 48-54. |

| [47] |

Park H, Shin H, Lee K, Holzapfel W. Autoinducer-2 properties of kimchi are associated with lactic acid bacteria involved in its fermentation[J]. International Journal of Food Microbiology, 2016, 225: 38-42. DOI:10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2016.03.007 |

| [48] |

Liu L, Wu RY, Zhang JL, Li PL. Overexpression of luxS promotes stress resistance and biofilm formation of Lactobacillus paraplantarum L-ZS9 by regulating the expression of multiple genes[J]. Frontiers in Microbiology, 2018, 9: 2628. DOI:10.3389/fmicb.2018.02628 |

| [49] |

Johansen P, Jespersen L. Impact of quorum sensing on the quality of fermented foods[J]. Current Opinion in Food Science, 2017, 13: 16-25. DOI:10.1016/j.cofs.2017.01.001 |

| [50] |

Wasfi R, El-Rahman OAA, Zafer MM, Ashour HM. Probiotic Lactobacillus sp. inhibit growth, biofilm formation and gene expression of caries-inducing Streptococcus mutans[J]. Journal of Cellular and Molecular Medicine, 2018, 22(3): 1972-1983. DOI:10.1111/jcmm.13496 |

| [51] |

Pezzulo AA, Hornick EE, Rector MV, Estin M, Reisetter AC, Taft PJ, Butcher SC, Carter AB, Manak JR, Stoltz DA, et al. Expression of human paraoxonase 1 decreases superoxide levels and alters bacterial colonization in the gut of Drosophila melanogaster[J]. PLoS One, 2012, 7(8): e43777. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0043777 |

| [52] |

Yao QF, Qi SH. Advance in quorum sensing autoinducers among microbes[J]. Journal of Microbiology, 2015, 35(4): 63-71. (in Chinese) 姚期凤, 漆淑华. 微生物群体效应信号分子研究进展[J]. 微生物学杂志, 2015, 35(4): 63-71. |

| [53] |

Pang XY, Zhu Q, Lu J, Zhang SW, Liu L, Yang L, Li WX, Lü JP. Progress in quorum sensing system of lactic acid bacteria[J]. Chinese Journal of Bioprocess Engineering, 2020, 18(2): 141-149. (in Chinese) 逄晓阳, 朱青, 芦晶, 张书文, 刘浏, 杨兰, 李伟勋, 吕加平. 乳酸菌群体感应系统研究进展[J]. 生物加工过程, 2020, 18(2): 141-149. |

| [54] |

Martino CD, Testa B, Letizia F, Iorizzo M, Lombardi SJ, Ianiro M, Renzo MD, Strollo D, Coppola R. Effect of exogenous proline on the ethanolic tolerance and malolactic performance of Oenococcus oeni[J]. Journal of Food Science and Technology, 2020, 57(11): 3973-3979. DOI:10.1007/s13197-020-04426-1 |

| [55] |

Betteridge A, Grbin P, Jiranek V. Improving Oenococcus oeni to overcome challenges of wine malolactic fermentation[J]. Trends in Biotechnology, 2015, 33(9): 547-553. DOI:10.1016/j.tibtech.2015.06.008 |

| [56] |

Jiang L, Cui HY, Zhu LY, Hu Y, Xu X, Li S, Huang H. Enhanced propionic acid production from whey lactose with immobilized Propionibacterium acidipropionici and the role of trehalose synthesis in acid tolerance[J]. Green Chemistry, 2015, 17(1): 250-259. DOI:10.1039/C4GC01256A |

| [57] |

Krulwich TA, Sachs G, Padan E. Molecular aspects of bacterial pH sensing and homeostasis[J]. Nature Reviews Microbiology, 2011, 9(5): 330-343. DOI:10.1038/nrmicro2549 |

| [58] |

Oncu S, Tari C, Unluturk S. Effect of various process parameters on morphology, rheology, and polygalacturonase production by Aspergillus sojae in a batch bioreactor[J]. Biotechnology Progress, 2007, 23(4): 836-845. DOI:10.1002/bp070079c |

| [59] |

Gao XP, He MC, Xu K, Li C. Research progress on pH regulation in the process of industrial microbial fermentation[J]. China Biotechnology, 2020, 40(6): 93-99. (in Chinese) 高小朋, 何猛超, 许可, 李春. 工业微生物发酵过程中pH调控研究进展[J]. 中国生物工程杂志, 2020, 40(6): 93-99. |

| [60] |

Deng N, Du H, Xu Y. Cooperative response of Pichia kudriavzevii and Saccharomyces cerevisiae to lactic acid stress in baijiu fermentation[J]. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry, 2020, 68(17): 4903-4911. DOI:10.1021/acs.jafc.9b08052 |

| [61] |

An J. Study on the factors affecting the stress reaction of lactic acid bacteria and its thermotolerance[D]. Wuhan: Master's Thesis of Huazhong Agricultural University, 2019(in Chinese) 安璟. 乳酸菌胁迫反应的影响因素及其耐热性的研究[D]. 武汉: 华中农业大学硕士学位论文, 2019 |

| [62] |

Fan ML. The effect of different vinegars on the chemical compositions of vinegar-baked herbs[D]. Taiyuan: Master's Thesis of Shanxi University, 2016(in Chinese) 范玛莉. 不同食醋对醋制中药的化学成分影响研究[D]. 太原: 山西大学硕士学位论文, 2016 |

| [63] |

Song NE, Cho SH, Baik SH. Microbial community, and biochemical and physiological properties of Korean traditional black raspberry (Robus coreanus Miquel) vinegar[J]. Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture, 2016, 96(11): 3723-3730. DOI:10.1002/jsfa.7560 |

| [64] |

Tanamool V, Chantarangsee M, Soemphol W. Simultaneous vinegar fermentation from a pineapple by-product using the co-inoculation of yeast and thermotolerant acetic acid bacteria and their physiochemical properties[J]. 3 Biotech, 2020, 10(3): 115. DOI:10.1007/s13205-020-2119-4 |

| [65] |

Deng YJ, Lu ZM, Zhang XJ, Chai LJ, Li X, Yu YJ, Li HZ, Shi JS, Xu ZH. Effects of lactic acid bacteria on the total acids and flavors of liquid fermented rice vinegar[J]. Food Science, 2020, 41(22): 97-102. (in Chinese) 邓永建, 陆震鸣, 张晓娟, 柴丽娟, 李信, 余永建, 李华钟, 史劲松, 许正宏. 不同乳酸菌对液态发酵米醋总酸及风味物质的影响[J]. 食品科学, 2020, 41(22): 97-102. |

| [66] |

Li Y, Song J, Xia ML, Ma YL, Zheng Y. Separation and purification of acid tolerant microorganisms from Yongchun aged vinegar and their application on grape vinegar fermentation[J]. China Brewing, 2017, 36(10): 120-124. (in Chinese) 李岩, 宋佳, 夏梦雷, 马应伦, 郑宇. 永春老醋耐酸微生物分离纯化及葡萄醋发酵应用[J]. 中国酿造, 2017, 36(10): 120-124. DOI:10.11882/j.issn.0254-5071.2017.10.025 |

| [67] |

Meng YH. Bacterial diversity during brewing processes of traditional vinegar by high-throughput sequencing[D]. Taiyuan: Master's Thesis of Shanxi University, 2019(in Chinese) 孟燕华. 利用高通量测序技术分析传统食醋酿造过程中的细菌多样性[D]. 太原: 山西大学硕士学位论文, 2019 |

| [68] |

Furukawa S, Watanabe T, Toyama H, Morinaga Y. Significance of microbial symbiotic coexistence in traditional fermentation[J]. Journal of Bioscience and Bioengineering, 2013, 116(5): 533-539. DOI:10.1016/j.jbiosc.2013.05.017 |

| [69] |

Xu Y, Wang D, Fan WL, Mu XQ, Chen J. Traditional Chinese biotechnology[J]. Advances in Biochemical Engineering/Biotechnology, 2010, 122: 189-233. DOI:10.1007/10_2008_36 |

| [70] |

Furukawa S, Nojima N, Yoshida K, Hirayama S, Ogihara H, Morinaga Y. The importance of inter-species cell-cell co-aggregation between Lactobacillus plantarum ML11-11 and Saccharomyces cerevisiae BY4741 in mixed-species biofilm formation[J]. Bioscience, Biotechnology, and Biochemistry, 2011, 75(8): 1430-1434. DOI:10.1271/bbb.100817 |

| [71] |

Tian ZW. Study on optimization of soy sauce brewing technology by solid and liquid fermentation[D]. Tianjin: Master's Thesis of Tianjin University of Science and Technology, 2019(in Chinese) 田子薇. 固稀发酵法酱油酿造工艺的优化研究[D]. 天津: 天津科技大学硕士学位论文, 2019 |

| [72] |

Cao ZH, Green-Johnson JM, Buckley ND, Lin QY. Bioactivity of soy-based fermented foods: a review[J]. Biotechnology Advances, 2019, 37(1): 223-238. DOI:10.1016/j.biotechadv.2018.12.001 |

| [73] |

Wah TT, Walaisri S, Assavanig A, Niamsiri N, Lertsiri S. Co-culturing of Pichia guilliermondii enhanced volatile flavor compound formation by Zygosaccharomyces rouxii in the model system of Thai soy sauce fermentation[J]. International Journal of Food Microbiology, 2013, 160(3): 282-289. DOI:10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2012.10.022 |

| [74] |

Guo J, Luo W, Fan J, Suyama T, Zhang WX. Co-inoculation of Staphylococcus piscifermentans and salt-tolerant yeasts inhibited biogenic amines formation during soy sauce fermentation[J]. Food Research International, 2020, 137: 109436. |

| [75] |

Devanthi PVP, Gkatzionis K. Soy sauce fermentation: microorganisms, aroma formation, and process modification[J]. Food Research International, 2019, 120: 364-374. |

| [76] |

Yan YZ, Qian YL, Ji FD, Chen JY, Han BZ. Microbial composition during Chinese soy sauce koji-making based on culture dependent and independent methods[J]. Food Microbiology, 2013, 34(1): 189-195. |

| [77] |

Zhang LQ, Zhou RQ, Cui RY, Huang J, Wu CD. Characterizing soy sauce moromi manufactured by high-salt dilute-state and low-salt solid-state fermentation using multiphase analyzing methods[J]. Journal of Food Science, 2016, 81(11): C2639-C2646. |

| [78] |

Li QY, Fang F, Du GC, Chen J. The application of Weissella strains in fermented food[J]. Food and Fermentation Industries, 2017, 43(10): 241-247. (in Chinese) 李巧玉, 方芳, 堵国成, 陈坚. 魏斯氏菌在发酵食品中的应用[J]. 食品与发酵工业, 2017, 43(10): 241-247. |

| [79] |

Noda F, Hayashi K, Mizunuma T. Antagonism between osmophilic lactic acid bacteria and yeasts in brine fermentation of soy sauce[J]. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 1980, 40(3): 452-457. |

| [80] |

Noda F, Hayashi K, Mizunuma T. Influence of pH on inhibitory activity of acetic acid on osmophilic yeasts used in brine fermentation of soy sauce[J]. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 1982, 43(1): 245-246. |

| [81] |

Kusumegi K, Yoshida H, Tomiyama S. Inhibitory effects of acetic acid on respiration and growth of Zygosaccharomyces rouxii[J]. Journal of Fermentation and Bioengineering, 1998, 85(2): 213-217. |

| [82] |

General Administration of Quality Supervision, Inspection and Quarantine of the People's Republic of China, Standardization Administration of the People's Republic of China. GB/T 17204-2008 Classification of alcoholic beverages[S]. Beijing: Standards Press of China, 2009(in Chinese) 中华人民共和国国家质量监督检验检疫总局, 中国国家标准化管理委员会. GB/T 17204-2008饮料酒分类[S]. 北京: 中国标准出版社, 2009 |

| [83] |

Liu D, Zhang PZ, Chen DL, Howell K. From the vineyard to the winery: how microbial ecology drives regional distinctiveness of wine[J]. Frontiers in Microbiology, 2019, 10: 2679. |

| [84] |

Liu WL, Li HM, Jiang DQ, Zhang Y, Zhang SC, Sun SY. Effect of Saccharomyces cerevisiae, Torulaspora delbrueckii and malolactic fermentation on fermentation kinetics and sensory property of black raspberry wines[J]. Food Microbiology, 2020, 91: 103551. |

| [85] |

Sun Y. Effects of different nitrogen levels on the characteristics and metabolites of Saccharomyces cerevisiae during mixed fermentation[D]. Yangling: Doctoral Dissertation of Northwest A & F University, 2016(in Chinese) 孙悦. 不同氮素水平对酿酒酵母混合发酵特征的影响及其代谢物研究[D]. 杨凌: 西北农林科技大学博士学位论文, 2016 |

| [86] |

Fujita K, Matsuyama A, Kobayashi Y, Iwahashi H. The genome-wide screening of yeast deletion mutants to identify the genes required for tolerance to ethanol and other alcohols[J]. FEMS Yeast Research, 2006, 6(5): 744-750. |

| [87] |

Casey GP, Ingledew WMM. Ethanol tolerance in yeasts[J]. CRC Critical Reviews in Microbiology, 1986, 13(3): 219-280. |

| [88] |

Bartle L, Sumby K, Sundstrom J, Jiranek V. The microbial challenge of winemaking: yeast-bacteria compatibility[J]. FEMS Yeast Research, 2019, 19(4): foz040. |

| [89] |

Branco P, Viana T, Albergaria H, Arneborg N. Antimicrobial peptides (AMPs) produced by Saccharomyces cerevisiae induce alterations in the intracellular pH, membrane permeability and culturability of Hanseniaspora guilliermondii cells[J]. International Journal of Food Microbiology, 2015, 205: 112-118. |

| [90] |

Sakamoto K, Konings WN. Beer spoilage bacteria and hop resistance[J]. International Journal of Food Microbiology, 2003, 89(2/3): 105-124. |

| [91] |

Le Lay C, Coton E, Le Blay G, Chobert JM, Haertlé T, Choiset Y, Van Long NN, Meslet-Cladière L, Mounier J. Identification and quantification of antifungal compounds produced by lactic acid bacteria and propionibacteria[J]. International Journal of Food Microbiology, 2016, 239: 79-85. |

| [92] |

Liu CX, Guo XW, Li LL, Tang QL, Wang YP, Xing S, Li ZJ, Xiao DG. Interactions of high ester producing Saccharomyces cerevisiae and lactic acid bacteria during co-fermentation[J]. Modern Food Science & Technology, 2017, 33(7): 79-84. (in Chinese) 刘彩霞, 郭学武, 李玲玲, 唐取来, 王亚平, 邢爽, 李镇江, 肖冬光. 高产酯酿酒酵母与乳酸菌共发酵过程中的相互作用研究[J]. 现代食品科技, 2017, 33(7): 79-84. |

| [93] |

Vriesekoop F, Krahl M, Hucker B, Menz G. 125th Anniversary Review: bacteria in brewing: the good, the bad and the ugly[J]. Journal of the Institute of Brewing, 2012, 118(4): 335-345. |

| [94] |

Luo QC, Zheng J, Zhao D, Qiao ZW, An MZ, Zhang X, Yang KZ. Interaction between dominant lactic acid bacteria and yeasts strains in strong aroma baijiu[J]. Chinese Journal of Applied and Environmental Biology, 2019, 25(5): 1192-1199. (in Chinese) 罗青春, 郑佳, 赵东, 乔宗伟, 安明哲, 张霞, 杨康卓. 浓香型白酒中优势乳酸菌和酵母菌间的相互关系[J]. 应用与环境生物学报, 2019, 25(5): 1192-1199. |

| [95] |

Shu L, He YG, Zhao XX, Liu YH, Li YQ. Identification and characteristic of lactic acid bacteria with high production of bacteriocin from pit mud of strong-flavor[J]. Science and Technology of Food Industry, 2019, 40(4): 119-124. (in Chinese) 舒梨, 何义国, 赵兴秀, 刘苑皓, 李义情. 浓香型窖泥中高产细菌素乳酸菌的鉴定及特性[J]. 食品工业科技, 2019, 40(4): 119-124. |

| [96] |

Yan B, He YF. A review on symbiotic mechanisms between lactic acid bacteria and yeasts[J]. Food Science, 2012, 33(3): 277-281. (in Chinese) 闫彬, 贺银凤. 乳酸菌与酵母菌共生机理综述[J]. 食品科学, 2012, 33(3): 277-281. |

| [97] |

Zhang Y, Du H, Wu Q, Xu Y. Impacts of two main lactic acid bacteria on microbial communities during Chinese Maotai-flavor liquor fermentation[J]. Microbiology China, 2015, 42(11): 2087-2097. (in Chinese) 张艳, 杜海, 吴群, 徐岩. 酱香型白酒发酵中两株主要乳酸菌对酿造微生物群体的影响[J]. 微生物学通报, 2015, 42(11): 2087-2097. |

| [98] |

Sieuwerts S, Bron PA, Smid EJ. Mutually stimulating interactions between lactic acid bacteria and Saccharomyces cerevisiae in sourdough fermentation[J]. LWT, 2018, 90: 201-206. |

| [99] |

Shou WY, Ram S, Vilar JMG. Synthetic cooperation in engineered yeast populations[J]. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 2007, 104(6): 1877-1882. |

2021, Vol. 48

2021, Vol. 48