扩展功能

文章信息

- 蒋刘一琦, 包黎明, 钱巧霞, 金力, 王久存

- JIANG Liu-Yi-Qi, BAO Li-Ming, QIAN Qiao-Xia, JIN Li, WANG Jiu-Cun

- 吸烟对健康人群唾液微生物组的影响

- Effect of smoking on salivary microbiome

- 微生物学通报, 2020, 47(9): 2913-2922

- Microbiology China, 2020, 47(9): 2913-2922

- DOI: 10.13344/j.microbiol.china.200735

-

文章历史

- 收稿日期: 2020-07-17

- 接受日期: 2020-08-14

- 网络首发日期: 2020-08-22

2. 复旦大学泰州健康科学研究院 江苏 泰州 225300

2. Taizhou Institute of Health Sciences, Fudan University, Taizhou, Jiangsu 225300, China

吸烟已经成为当今世界最重要的公共健康问题之一。近30年来,中国烟草消费量急剧增加。2015年的调查数据显示,中国成年男性的吸烟率为52.1%[1]。吸烟是许多疾病的危险因素,如咽喉癌、大肠癌、口腔癌、胃溃疡、牙周炎等[2-4]。

口腔是最早接触烟草和烟雾并受其影响的部位。人类的口腔中定殖着700多种微生物,统称为口腔微生物组[5]。越来越多的证据表明口腔微生物组对口腔健康乃至全身健康具有重要的作用,口腔微生物组的失调可能会导致牙周炎、龋齿、癌症等疾病的发生[6]。此外,研究发现不同人群口腔微生物组的多样性和组成存在差异,这一差异可能与宿主的饮食习惯、生活环境、遗传背景等有关[7-10]。因此,在某一特定人群中观察到的口腔微生物组变化的结果可能不适用于另一人群,即需要对不同人群进行研究,以更好地理解口腔微生物组在健康中的作用。

多项研究表明,吸烟会影响口腔微生物组,但研究结果并不完全一致[3, 11-15]。这可能是由于采集的人群、样本量、采样位置以及实验方法等因素的不同所致。考虑到先前的研究主要来自于西方国家,对中国人群的关注很少,尤其缺少对中国健康人群的研究,所以探究吸烟对中国健康人群口腔微生物组的影响,对填补口腔微生物组对健康影响的知识空缺具有重要意义。

唾液作为口腔微生物组的采集部位之一,具有易于收集且无创的特征。而且与其他位置的口腔微生物相比,唾液微生物具有可通过唾液的转移与肠道微生物发生相互作用、进而影响宿主健康的特点,因此,唾液微生物组是疾病诊断和预后的理想标志物。

综上,本研究收集了167名健康个体的唾液样品,并通过对样品中16S rRNA基因V3-V4区序列进行测序,评估吸烟对唾液微生物组的影响。

1 材料与方法 1.1 研究对象从江苏泰州人群健康跟踪调查项目(Taizhou longitudinal study,TZL)中选取健康受试者。纳入标准:(1)未患有龋齿、牙周病、心血管疾病、病毒感染、自身性疾病、代谢疾病及肿瘤等疾病;(2)一个月内未使用抗生素药物;(3)女性不在妊娠期。最终纳入167名受试者,年龄在20-60岁之间,平均年龄为38.29±9.87岁。其中,从不吸烟者为90人,平均年龄为37.01±9.61岁;吸烟者为77人,平均年龄为39.78±10.02岁,两组间年龄没有统计学差异。

1.2 主要试剂和仪器DNA提取试剂盒,天根生化科技(北京)有限公司;AxyPrepDNA凝胶回收试剂盒,Axygen公司。PCR仪、电泳仪和凝胶成像系统,Bio-Rad公司;HiSeq 2000测序仪,Illumina公司。

1.3 样本采集所有受试者在样品采集前30 min内无进食、咀嚼口香糖或使用漱口水等。使用50 mL无菌离心管收集唾液2 mL,并存放于-80 ℃冰箱内。

1.4 DNA抽提与测序使用DNA提取试剂盒进行总DNA的提取,用琼脂糖凝胶电泳检测DNA完整性。对细菌基因组DNA的16S rRNA基因V3-V4可变区进行PCR扩增,正向引物为338F (5′-GTACTCCTACGGGAGGCAGCA-3′),反向引物为806R (5′-GTGGACTACHVGGGTWTCTAAT-3′)。PCR反应体系(20 μL):5×FastPfu DNA聚合酶缓冲液4 μL,dNTPs (2.5 mmol/L) 2 μL,上、下游引物(5 μmol/L)各0.8 μL,FastPfu聚合酶(5 mol/L) 0.4 μL,DNA模板10 ng,ddH2O补足20 μL。PCR反应条件:95 ℃ 3 min;95 ℃ 30 s,55 ℃ 30 s,72 ℃ 30 s,27个循环;72 ℃ 10 min。根据Illumina DNA文库制备说明书构建基因文库,在Illumina HiSeq 2000平台进行测序。

1.5 数据处理利用FLASH V1.2.11[16]和QIIME V1.9.0[17]软件对测序得到的原始数据进行拼接、筛选,得到有效序列。按照97%的相似度进行操作分类单元(operational taxonomic unit,OTU)聚类。运用RDP Classifier与GreenGene V13.8数据库进行物种注释分析,用PICRUSt V1.1.0软件[18]对细菌的功能进行预测。通过计算Shannon、Simpson等α多样性指数,比较α多样性差异;基于Bray-Curtis距离进行主成分分析(principal component analysis,PCA),以表征β多样性。

1.6 统计学分析与图表绘制两组间采用Wilcoxon rank-sum test检验比较α多样性、差异细菌,P值小于0.05表明差异有统计学意义。运用Adonis检验比较两组间β多样性,用Spearman Rank进行差异细菌的相关性分析。运用LEfSe比较两组间的菌群功能差异,LDA的筛选值为2。运用Cytoscape 3.7[19]进行网络图的绘制,使用R语言3.5.0完成其他图表的绘制。

2 结果与分析 2.1 样本信息及测序数据统计167个样本测序共获得9 457 730条有效序列。在97%的相似水平下,对样本进行聚类和注释,共得到4 001个OTU,归属于18个菌门106个菌科193个菌属。吸烟组和非吸烟组的志愿者信息见表 1。

| Items | Current (n=77) |

Never (n=90) |

P value |

| Age, Mean (SD) | 39.78 (10.02) | 37.01 (9.61) | 0.08 |

| Young (21-35), n | 27 | 37 | |

| Middle (36-50), n | 38 | 46 | |

| Aged (> 50), n | 12 | 7 |

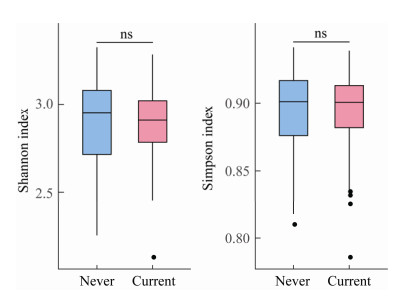

吸烟组(current)与非吸烟组(never)比较,α多样性(图 1,Shannon指数和Simpson指数)无显著差异。

|

| 图 1 唾液菌群的Shannon指数和Simpson指数箱型图 Figure 1 Boxplot of Shannon index and Simpson index 注:Never:非吸烟组;Current:吸烟组. ns:P > 0.05. Note: Never: Non-smoking group; Current: Smoking group. ns: P > 0.05. |

|

|

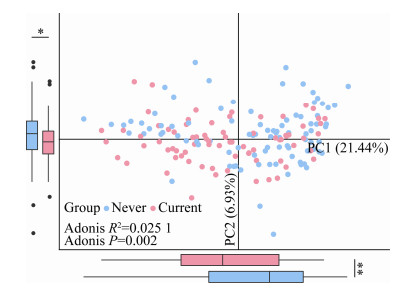

在OTU水平上,基于Bray-Curtis距离对所有样品进行主成分分析后发现,吸烟组和非吸烟组比较存在一定的差异,差异具有统计学意义(Adonis:R2=0.025 1,P=0.002;图 2)。

|

| 图 2 基于OTU水平的PCA分析 Figure 2 PCA of bacterial OTU composition 注:Never:非吸烟组;Current:吸烟组.每个点代表一个样本,粉色的点为吸烟组,蓝色的点代表非吸烟组.箱型图展示了吸烟组(粉色)和非吸烟组(蓝色)在PC1和PC2上的差异.使用Adonis进行检验(左下角). *:P < 0.05;**:P < 0.01. Note: Never: Non-smoking group; Current: Smoking group. Each point represented one sample, pink indicated smoking group, blue indicated non-smoking group. Box plots quantified the dissimilarity of PC1 and PC2 between the two groups. The Adonis test was used to determine significance between the two groups (shown in the lower left). *: P < 0.05; **: P < 0.01. |

|

|

非吸烟组和吸烟组的唾液菌群组成见图 3。在门水平上(图 3A),按照相对丰度从高到低依次是拟杆菌门(Bacteroidetes,非吸烟组:35.62%;吸烟组:39.46%)、厚壁菌门(Firmicutes,非吸烟组:24.48%;吸烟组:27.37%)、变形菌门(Proteobacteria,非吸烟组:24.19%;吸烟组:17.16%)、梭杆菌门(Fusobacteria,非吸烟组:7.04%;吸烟组:6.04%)、放线菌门(Actinobacteria,非吸烟组:2.77%;吸烟组:4.03%)。

|

| 图 3 吸烟者和非吸烟者的唾液菌群构成 Figure 3 Composition of salivary microbiome of smokers and non-smokers 注:Never:非吸烟组;Current:吸烟组.柱状图(左)为非吸烟组/吸烟组全部样本的细菌组成情况.堆积图(右)为非吸烟组/吸烟组各样本的细菌组成情况. A:门水平;B:属水平. Note: Never: Non-smoking group; Current: Smoking group. Bar plot (Left) showed the bacterial composition of all samples in smoking group/non-smoking group. Area plot showed the bacterial composition of each sample in smoking group/non-smoking group. A: Phylum level; B: Genus level. |

|

|

在属水平上(图 3C),按照相对丰度从高到低,前十位依次是普雷沃氏菌属1 (Prevotella1,非吸烟组:19.12%;吸烟组:22.63%)、奈瑟菌属(Neisseria,非吸烟组:14.46%;吸烟组:10.06%)、普雷沃氏菌属2 (Prevotella2,非吸烟组:8.07%;吸烟组:8.78%)、韦荣氏球菌属(Veillonella,非吸烟组:7.01%;吸烟组:9.03%)、链球菌属(Streptococcus,非吸烟组:7.56%;吸烟组:7.46%)、卟啉单胞菌属(Porphyromonas,非吸烟组:5.68%;吸烟组:6.08%)、梭杆菌属(Fusobacterium,非吸烟组:4.17%;吸烟组:3.85%)、嗜血杆菌属(Haemophilus,非吸烟组:3.05%;吸烟组:2.49%)、纤毛菌属(Leptotrichia,非吸烟组:2.21%;吸烟组:1.74%)、罗斯氏菌属(Rothia,非吸烟组:1.59%;吸烟组:2.14%)。

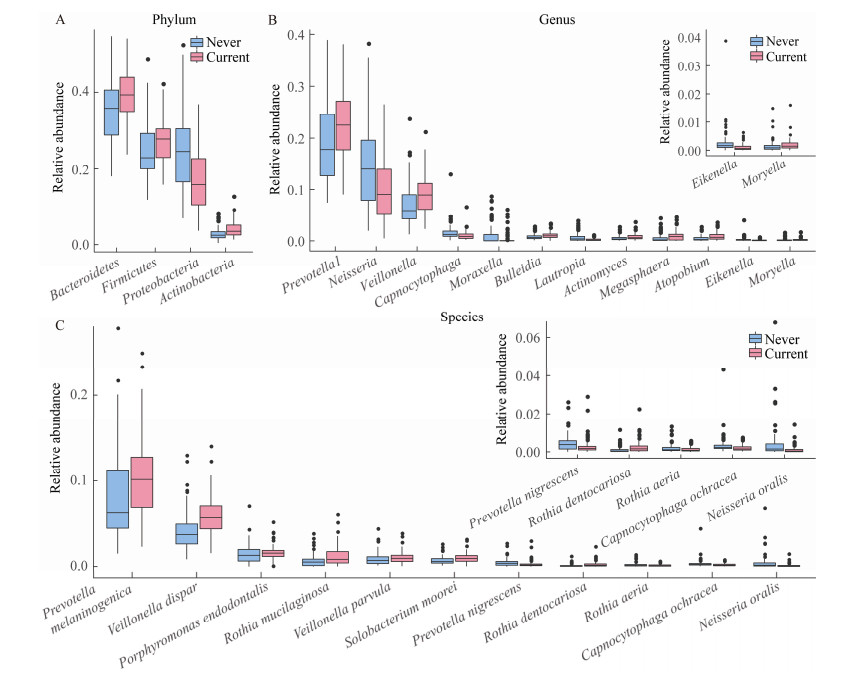

通过Wilcoxon rank-sum test检验比较两组间的差异细菌,发现有多个优势菌门和优势菌属存在差异(图 4)。在门水平上(图 4A),与非吸烟组相比,吸烟组中拟杆菌门(Bacteroidetes)、厚壁菌门(Firmicutes)和放线菌门(Actinobacteria)的相对丰度显著升高,变形菌门(Proteobacteria)的相对丰度显著下降。

|

| 图 4 吸烟者与非吸烟者的差异细菌 Figure 4 Differential bacteria between smokers and non-smokers 注:Never:非吸烟组;Current:吸烟组.仅展示相对丰度大于0.1%的差异细菌. A:门水平;B:属水平;C:种水平.右上角的箱型图进一步展示了相对丰度较低的菌属和菌种. Note: Never: Non-smoking group; Current: Smoking group. Only differential bacteria with relative abundance > 0.1% were shown. A: Phylum level; B: Genus level; C: Species level. The box plot (upper right) further showed the genus and species with low relative abundance. |

|

|

在属水平上(图 4B),与非吸烟组相比,吸烟组中普雷沃氏菌属(Prevotella)、韦荣氏球菌(Veillonella)、布雷德菌属(Bulleidia)、放线菌属(Actinomyces)、巨球型菌属(Megasphaera)、奇异菌属(Atopobium)和毛螺菌属(Moryella)的相对丰度显著升高,奈瑟菌属(Neisseria)、二氧化碳嗜纤维属(Capnocytophaga)、莫拉菌属(Moraxella)、劳特罗普氏菌属(Lautropia)和艾肯菌属(Eikenella)的相对丰度显著降低。在种水平上,共检测到246个具有分类命名的菌种,其中相对丰度大于0.1%且存在显著差异的有11种。黑色素杆菌(Prevotella melaninogenica)、殊异韦荣菌(Veillonella dispar)、牙髓卟啉单胞菌(Porphyromonas endodontalis)、粘滑罗斯菌(Rothia mucilaginosa)、小韦荣球菌(Veillonella parvula)、梭状芽孢杆菌(Solobacterium moorei)和龋齿罗氏菌(Rothia dentocariosa)等菌种富集于吸烟组,变黑普氏菌(Prevotella nigrescens)、黄褐二氧化碳嗜纤维菌(Capnocytophaga ochracea)和口腔奈瑟菌(Neisseria oralis)等菌种富集于非吸烟组。

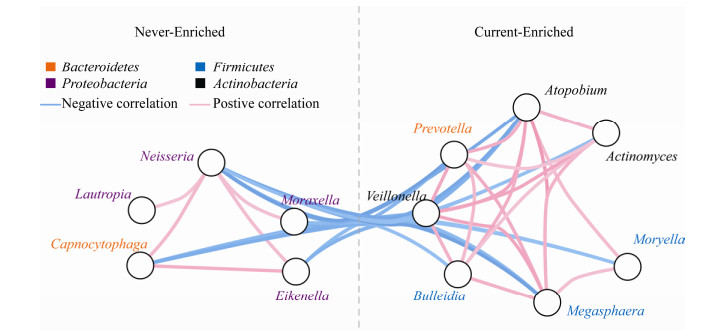

2.5 差异细菌的相关性分析对吸烟组和非吸烟组之间存在差异的菌属进行相关性分析,发现富集于同一组的细菌之间均呈显著正相关,而富集于不同组的细菌之间均呈显著负相关(图 5)。

|

| 图 5 差异细菌的相关性分析 Figure 5 Correlations of differential bacteria 注:使用Spearman rank计算差异细菌间的相关性.仅显示相关性(rho值)大于0.4或小于-0.4的关联.每个圆圈代表一个属.位于虚线左边的细菌富集于非吸烟组(never),位于虚线右边的细菌富集于吸烟组(current).线的颜色表示相关性的大小,蓝色代表负相关,粉色代表正相关,颜色越深,相关性越强.菌属名称的颜色代表其所对应的门水平分类. Note: The correlation of differential bacteria was calculated by spearman rank. Only correlations with rho value > 0.4 or <-0.4 were shown. Each circle represented one genus. Genus enriched in non-smoking group (never) were shown on the left side, while genus enriched in smoking group (current) were shown on the right side. Connect lines in blue or pink indicated negative or positive correlation respectively, and darker color showed stronger correlation. The color of genus name represented the phylum level. |

|

|

基于PICRUSt的预测结果,运用LDA方法判定吸烟组和非吸烟组存在差异的功能,发现部分唾液菌群功能存在显著差异(图 6)。

|

| 图 6 唾液菌群的功能差异 Figure 6 Functional differences of salivary microbiome 注:柱状图展示了KEGG Level 3的结果.粉色代表该功能富集于吸烟组(current),蓝色代表该功能富集于非吸烟组(never).分析时LDA阈值设置为2.0.柱状图的长度代表差异功能的LDA值大小. LDA值的绝对值越大代表差异越显著. Note: The bar plot showed the results of KEGG Level 3. Pink represented the functions enriched in smoking group (current), and blue represented the functions enriched in non-smoking group (never). The threshold on the LDA score was set to 2.0. The length of bar represented the LDA score, and the larger the LDA score, the better the function differentiates. |

|

|

差异分析结果显示,吸烟组和非吸烟组主要在遗传信息处理和代谢相关的通路上存在差异。核糖体(ribosome)、DNA修复和重组蛋白(DNA repair and recombination proteins)、氨酰-tRNA的生物合成(aminoacyl-tRNA biosynthesis)、DNA复制蛋白(DNA replication proteins)、果糖和甘露糖代谢(fructose and mannose metabolism)、半乳糖代谢(galactose metabolism)、淀粉和蔗糖的代谢(starch and sucrose metabolism)等功能富集于吸烟组。

缬氨酸和亮氨酸及异亮氨酸的生物合成(valine,leucine and isoleucine biosynthesis)、精氨酸和脯氨酸的代谢(arginine and proline metabolism)、氧化磷酸化(oxidative phosphorylation)、丙酮酸代谢(pyruvate metabolism)、脂质生物合成蛋白(lipid biosynthesis proteins)、脂肪酸的生物合成(fatty acid biosynthesis)、脂多糖生物合成蛋白质(lipopolysaccharide biosynthesis proteins)、甘油磷脂的代谢(glycerophospholipid metabolism)等功能富集于非吸烟组。

3 讨论与结论全世界约有20亿人使用烟草产品,与烟草相关的疾病每年至少导致400万人死亡[20]。近年来,与烟草相关的疾病,包括心血管疾病、慢性阻塞性肺疾病、克罗恩病和各类癌症的发生率更是急剧上升[21]。这些数据都表明吸烟在人类疾病发生中具有潜在的危害。然而新的证据已经表明,主动吸烟或暴露于二手烟环境都与潜在病原菌的定殖有关[22-23]。但目前关于吸烟对中国人群口腔微生物组影响的研究十分有限。基于此,本研究收集了167名健康个体的唾液样本,利用16S rRNA基因扩增子测序法探究了吸烟对唾液微生物组的影响。

前人研究发现,吸烟会造成唾液微生物组的α多样性下降[12, 24],但也有报道指出,吸烟者和非吸烟者唾液微生物组的α多样性没有显著差异[25]。在本研究中,Shannon指数和Simpson指数的比较结果显示,吸烟对唾液微生物组的α多样性不会造成显著影响,但相比非吸烟组,吸烟组唾液微生物组的α多样性有下降趋势。在β多样性上,PCA的分析结果显示吸烟组和非吸烟组的唾液微生物组的结构存在一定差异,表明吸烟会对唾液微生物组造成一定的影响。

虽然人体唾液微生物组中含有多种微生物,但拟杆菌门(Bacteroidetes)、厚壁菌门(Firmicutes)、变形菌门(Proteobacteria)、梭杆菌门(Fusobacteria)和放线菌门(Actinobacteria)被认为是最主要的5个菌门[26],这与本研究结果相一致。在本研究中,167个样本的唾液微生物均发现了上述5个菌门,平均总相对丰度为94.08%。其中,主要包含普雷沃氏菌属1 (Prevotella1)、奈瑟菌属(Neisseria)、普雷沃氏菌属2 (Prevotella2)、韦荣氏球菌属(Veillonella)、链球菌属(Streptococcus)、卟啉单胞菌属(Porphyromonas)、梭杆菌属(Fusobacterium)、嗜血杆菌属(Haemophilus)、纤毛菌属(Leptotrichia)和罗斯氏菌属(Rothia)等菌属,上述菌属均常见于人类口腔[26]。

先前的研究表明,吸烟会改变健康人群唾液微生物组的组成,但是研究结果不尽相同。一项针对美国健康人群的大型研究发现,吸烟会导致唾液微生物中变形菌门的相对丰度降低,放线菌门的相对丰度升高[14]。另一项针对约旦健康人群的研究发现,吸烟者的唾液微生物组中厚壁菌门增加,而变形菌门和梭杆菌门减少[12]。在本研究中,与非吸烟组相比,吸烟组的变形菌门、厚壁菌门、放线菌门以及拟杆菌门的相对丰度发生明显变化。

为进一步明确吸烟对唾液微生物组的影响,本研究比较了属水平和种水平的细菌差异,发现吸烟对多个菌属和菌种的相对丰度造成了影响。在属水平上,有研究发现,吸烟会导致健康人唾液中奈瑟菌属、二氧化碳嗜纤维属(Capnocytophaga)和劳特罗普氏菌属(Lautropia)的减少[12, 25, 27],这与本研究结果相符。本研究还发现,吸烟组的艾肯菌属(Eikenella)相对丰度降低,这与某些疾病状态的唾液微生物改变一致,如在牙周炎患者的口腔黏膜中奈瑟菌属和艾肯菌属的相对丰度降低[28]。

此外,本研究结果显示,吸烟组中普雷沃氏菌属、韦荣氏球菌属、放线菌属(Actinomyces)、奇异菌属(Atopobium)和巨球型菌属(Megasphaera)等菌属的相对丰度显著升高。有研究表明,韦荣氏球菌属和放线菌属中的某些细菌能够参与硝酸盐的还原反应,将硝酸盐转化为亚硝酸盐,再进一步将亚硝酸盐转化为致癌的亚硝胺和促炎的一氧化氮[29-30]。由于吸烟能够增加硝酸盐和生物碱的口服摄入量,因此这些微生物可能会通过参与硝酸盐的代谢对人体健康产生重要影响[31]。普雷沃氏菌属、韦荣氏球菌属和放线菌属的部分细菌可以产生硫化氢,被认为是口腔恶臭的来源[32]。因此,这些细菌属的相对丰度增加可能是造成吸烟者口腔存在异味的原因之一。另外有报道指出,吸烟会造成唾液中链球菌属(Streptococcus)的相对丰度增加[12, 24],但是本研究中链球菌属的相对丰度无显著变化。

在种水平上,Lin等发现吸烟组富集粘滑罗斯菌(Rothia mucilaginosa)、连翘坦纳氏菌(Tannerella forsythia)、具核梭杆菌(Fusobacterium nucleatum)、普雷沃菌(Prevotella spp.)和Eubacterium saphenum等细菌[27]。本研究结果也显示,吸烟组中粘滑罗斯菌和黑色素杆菌(Prevotella melaninogenica)的相对丰度增加。此外,本研究还发现吸烟会造成健康人唾液中的牙髓卟啉单胞菌(Porphyromonas endodontalis)和梭状芽孢杆菌(Solobacterium moorei)相对丰度增加。有报道指出,牙髓卟啉单胞菌与慢性牙周炎存在关联[33],而梭状芽孢杆菌被发现与口臭相关[34]。上述结果为吸烟引起口腔疾病提供了潜在解释,并为预测和治疗疾病提供了潜在靶点。

对差异菌属进行相关性分析发现,富集于同一个组的细菌之间呈现强正相关,而富集于不同组的细菌之间呈现强的负相关。由于细菌定殖生态位主要由营养、空间环境和代谢等因素决定[35],因此该强共现网络的出现提示我们吸烟在物种选择中起关键作用。

PICRUSt预测结果显示,与非吸烟者相比,吸烟者唾液微生物组的部分功能发生显著变化。在吸烟者中,有氧代谢相关的途径(氧化磷酸化)相对丰度显著降低,而不依赖氧气的代谢途径(果糖、半乳糖、蔗糖等糖代谢)的相对丰度明显上升,这可能与吸烟造成的缺氧环境有关[36]。

综上所述,本研究表明吸烟会影响人体唾液微生物组,其可能会通过降低健康正常唾液细菌的丰度和增加有害菌的丰度破坏唾液微生物组的稳态,从而导致与吸烟相关疾病的患病风险增加。未来的研究需要进一步通过宏基因组的方法验证吸烟对唾液微生物组功能的影响,并确定与吸烟相关的口腔细菌是否介导吸烟对健康的影响。此外,还应该进一步探究差异细菌是否可以作为诊断性生物标记物,预测与吸烟相关疾病的发生。

| [1] |

Zou XN, Jia MM, Wang X, et al. Changing epidemic of lung cancer & tobacco and situation of tobacco control in China[J]. Chinese Journal of Lung Cancer, 2017, 20(8): 505-510. (in Chinese) 邹小农, 贾漫漫, 王鑫, 等. 中国肺癌和烟草流行及控烟现状[J]. 中国肺癌杂志, 2017, 20(8): 505-510. |

| [2] |

Stämpfli MR, Anderson GP. How cigarette smoke skews immune responses to promote infection, lung disease and cancer[J]. Nature Reviews Immunology, 2009, 9(5): 377-384. |

| [3] |

Kumar PS, Matthews CR, Joshi V, et al. Tobacco smoking affects bacterial acquisition and colonization in oral biofilms[J]. Infection and Immunity, 2011, 79(11): 4730-4738. |

| [4] |

Warren GW, Alberg AJ, Kraft AS, et al. The 2014 Surgeon general's report: "The health consequences of smoking— 50 years of progress": a paradigm shift in cancer care[J]. Cancer, 2014, 120(13): 1914-1916. |

| [5] |

Socransky SS, Haffajee AD. Periodontal microbial ecology[J]. Periodontology 2000, 2005, 38(1): 135-187. |

| [6] |

Kumar PS, Griffen AL, Moeschberger ML, et al. Identification of candidate periodontal pathogens and beneficial species by quantitative 16S clonal analysis[J]. Journal of Clinical Microbiology, 2005, 43(8): 3944-3955. |

| [7] |

Takeshita T, Matsuo K, Furuta M, et al. Distinct composition of the oral indigenous microbiota in South Korean and Japanese adults[J]. Scientific Report, 2014, 4: 6990. |

| [8] |

Li J, Quinque D, Horz HP, et al. Comparative analysis of the human saliva microbiome from different climate zones: Alaska, Germany, and Africa[J]. BMC Microbiology, 2014, 14: 316. |

| [9] |

Bhushan B, Yadav AP, Singh SB, et al. Diversity and functional analysis of salivary microflora of Indian Antarctic expeditionaries[J]. Journal of Oral Microbiology, 2019, 11(1): 1581513. |

| [10] |

Nasidze I, Li J, Schroeder R, et al. High diversity of the saliva microbiome in Batwa Pygmies[J]. PLoS One, 2011, 6(8): e23352. |

| [11] |

Morris A, Beck JM, Schloss PD, et al. Comparison of the respiratory microbiome in healthy nonsmokers and smokers[J]. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine, 2013, 187(10): 1067-1075. |

| [12] |

Al-Zyoud W, Hajjo R, Abu-Siniyeh A, et al. Salivary microbiome and cigarette smoking: a first of its kind investigation in Jordan[J]. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 2020, 17(1): 256. |

| [13] |

Karabudak S, Ari O, Durmaz B, et al. Analysis of the effect of smoking on the buccal microbiome using next-generation sequencing technology[J]. Journal of Medical Microbiology, 2019, 68(8): 1148-1158. |

| [14] |

Wu J, Peters BA, Dominianni C, et al. Cigarette smoking and the oral microbiome in a large study of American adults[J]. The ISME Journal, 2016, 10(10): 2435-2446. |

| [15] |

Karasneh JA, Al Habashneh RA, Marzouka NAS, et al. Effect of cigarette smoking on subgingival bacteria in healthy subjects and patients with chronic periodontitis[J]. BMC Oral Health, 2017, 17(1): 64. |

| [16] |

Magoč T, Salzberg SL. FLASH: fast length adjustment of short reads to improve genome assemblies[J]. Bioinformatics, 2011, 27(21): 2957-2963. |

| [17] |

Caporaso JG, Kuczynski J, Stombaugh J, et al. QⅡME allows analysis of high-throughput community sequencing data[J]. Nature Methods, 2010, 7(5): 335-336. |

| [18] |

Langille MGI, Zaneveld J, Caporaso JG, et al. Predictive functional profiling of microbial communities using 16S rRNA marker gene sequences[J]. Nature Biotechnology, 2013, 31(9): 814-821. |

| [19] |

Shannon P, Markiel A, Ozier O, et al. Cytoscape: a software environment for integrated models of biomolecular interaction networks[J]. Genome Research, 2003, 13(11): 2498-2504. |

| [20] |

DeMarini DM. Genotoxicity of tobacco smoke and tobacco smoke condensate: a review[J]. Mutation Research/Reviews in Mutation Research, 2004, 567(2/3): 447-474. |

| [21] |

Huang C, Shi G. Smoking and microbiome in oral, airway, gut and some systemic diseases[J]. Journal of Translational Medicine, 2019, 17(1): 225. |

| [22] |

Brook I, Gober AE. Recovery of potential pathogens and interfering bacteria in the nasopharynx of smokers and nonsmokers[J]. Chest, 2005, 127(6): 2072-2075. |

| [23] |

Shiloah J, Patters MR, Waring MB. The prevalence of pathogenic periodontal microflora in healthy young adult smokers[J]. Journal of Periodontology, 2000, 71(4): 562-567. DOI:10.1902/jop.2000.71.4.562 |

| [24] |

Yu GQ, Phillips S, Gail MH, et al. The effect of cigarette smoking on the oral and nasal microbiota[J]. Microbiome, 2017, 5(1): 3. |

| [25] |

Wirth R, Maróti G, Mihók R, et al. A case study of salivary microbiome in smokers and non-smokers in Hungary: analysis by shotgun metagenome sequencing[J]. Journal of Oral Microbiology, 2020, 12(1): 1773067. |

| [26] |

Belstrøm D. The salivary microbiota in health and disease[J]. Journal of Oral Microbiology, 2020, 12(1): 1723975. |

| [27] |

Lin DD, Hutchison KE, Portillo S, et al. Association between the oral microbiome and brain resting state connectivity in smokers[J]. Neuroimage, 2019, 200: 121-131. |

| [28] |

Mager DL, Haffajee AD, Socransky SS. Effects of periodontitis and smoking on the microbiota of oral mucous membranes and saliva in systemically healthy subjects[J]. Journal of Clinical Periodontology, 2003, 30(12): 1031-1037. |

| [29] |

Doel JJ, Benjamin N, Hector MP, et al. Evaluation of bacterial nitrate reduction in the human oral cavity[J]. European Journal of Oral Sciences, 2005, 113(1): 14-19. |

| [30] |

Liddle L, Burleigh MC, Monaghan C, et al. Variability in nitrate-reducing oral bacteria and nitric oxide metabolites in biological fluids following dietary nitrate administration: an assessment of the critical difference[J]. Nitric Oxide, 2019, 83: 1-10. |

| [31] |

Kato I, Vasquez AA, Moyerbrailean G, et al. Oral microbiome and history of smoking and colorectal cancer[J]. Journal of Epidemiological Research, 2016, 2(2): 92-101. |

| [32] |

Crielaard W, Zaura E, Schuller AA, et al. Exploring the oral microbiota of children at various developmental stages of their dentition in the relation to their oral health[J]. BMC Medical Genomics, 2011, 4: 22. |

| [33] |

Lombardo Bedran TB, Marcantonio RAC, Spin Neto R, et al. Porphyromonas endodontalis in chronic periodontitis: a clinical and microbiological cross-sectional study[J]. Journal of Oral Microbiology, 2012, 4(1): 10123. |

| [34] |

Vancauwenberghe F, Dadamio J, Laleman I, et al. The role of Solobacterium moorei in oral malodour[J]. Journal of Breath Research, 2013, 7(4): 046006. |

| [35] |

Keddy PA. Assembly and response rules: two goals for predictive community ecology[J]. Journal of Vegetation Science, 1992, 3(2): 157-164. |

| [36] |

Kenney EB, Saxe SR, Bowles RD. The effect of cigarette smoking on anaerobiosis in the oral cavity[J]. Journal of Periodontology, 1975, 46(2): 82-85. |

2020, Vol. 47

2020, Vol. 47