扩展功能

文章信息

- 卢亚兰, 代正云, 陈凌云, 陈怡飞, 孙东昌, 杨华, 唐标

- LU Ya-Lan, DAI Zheng-Yun, CHEN Ling-Yun, CHEN Yi-Fei, SUN Dong-Chang, YANG Hua, TANG Biao

- 两株blaNDM-5基因介导的碳青霉烯耐药禽源大肠杆菌ST10和ST354耐药性

- Two carbapenem-resistant avian Escherichia coli strains ST10 and ST354 mediated by blaNDM-5 gene

- 微生物学通报, 2020, 47(6): 1837-1846

- Microbiology China, 2020, 47(6): 1837-1846

- DOI: 10.13344/j.microbiol.china.190856

-

文章历史

- 收稿日期: 2019-10-24

- 接受日期: 2019-12-31

- 网络首发日期: 2020-02-21

2. 浙江省农业科学院农产品质量标准研究所 浙江 杭州 310021;

3. 湖南科技学院化学与生物工程学院 湖南 永州 425000

2. Institute of Quality and Standard for Agro-products, Zhejiang Academy of Agricultural Sciences, Hangzhou, Zhejiang 310021, China;

3. College of Chemistry and Biological Engineering, Hunan University of Science and Engineering, Yongzhou, Hunan 425000, China

碳青霉烯类抗生素是一种抗菌谱广、抗菌活性较强的β-内酰胺类抗生素,因其具有对β-内酰胺酶稳定以及毒性低等特点,已经成为治疗严重细菌感染的最主要抗菌药物之一。然而随着碳青霉烯类药物使用的增加,含碳青霉烯耐药基因的菌株已经陆续被发现,特别是碳青霉烯耐药肠杆菌科菌株的发现,对公共健康造成巨大威胁。从2009年Yong等首次在克雷伯氏菌中发现了新德里金属-β-内酰胺酶-1 (new delhi metallo-β-lactamase-1,NDM-1)以来[1],世界各地也相继发现了携带blaNDM的细菌[2-5]。到目前为止,已经发现了24个blaNDM变型体[6]。blaNDM-5最早是在2011年由Hornsey等首次在大肠杆菌中发现[7]并引起了广泛关注,紧接着很多国家也陆续报道了携带blaNDM-5的肠杆菌科菌株,成为流行广泛的blaNDM变型体之一[8-11]。blaNDM-5可通过不同类型质粒介导,例如IncF、IncN和IncX3等[12]。其中,IncX3型质粒在肠杆菌科中宿主范围较窄[13]。目前许多国家在人、动物和环境之中发现了携带blaNDM-5的IncX3型质粒的肠杆菌科菌株,包括澳大利亚[14]、印度[15]、韩国[16]、日本[17]、尼日利亚[18]、阿拉伯联合酋长国[19]等。在中国,已有很多省市报道了人来源的携带blaNDM-5的IncX3型质粒,包括浙江[6, 13, 20]、江苏[21]、山东[22]、上海[23]、青海[24]、四川[25]等,而从动物中分离的报道仅占极少数。

本研究从浙江和陕西家禽的粪便中分离出碳青霉烯类耐药的两株序列型分别为ST354和ST10的大肠杆菌HN1-26和XN3-1,这两株菌均携带blaNDM-5基因。通过全基因组测序、药敏检测等手段解析了耐药机制,并对两株菌的耐药性和耐药质粒进行了比较分析。这些研究结果将有助于增加研究者对携带blaNDM-5基因的质粒在人和动物中传播规律的认知。

1 材料与方法 1.1 主要试剂和仪器DNA提取试剂盒,上海捷瑞生物工程有限公司;BiofosunⓇ革兰氏阴性需氧菌药敏板,上海星佰生物技术有限公司;美罗培南,大连美仑生物技术有限公司。微生物自动生长曲线测定仪Microscreen,杰灵仪器制造(天津)有限公司;细菌鉴定质谱,Bruker公司。

1.2 菌株分离、鉴定2018年10-12月,分别从陕西西安一家庭养鸡场和浙江海宁两个鸭养殖场各采集粪便样品5、10和10份,使用含有美罗培南浓度为4 μg/mL的LB平板进行筛选,挑选疑似克隆后纯化3次,通过基质辅助激光解吸电离飞行时间质谱(matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time of flight mass spectrometry,MALDI-TOF MS)快速鉴定。获得的菌株通过16S rRNA基因扩增[26]比对,最后使用20%甘油保藏到-80 ℃冰箱。将分离株划线于LB平板,37 ℃培养12-24 h复苏,挑单克隆用于后续研究。

1.3 基因组DNA提取与测序分离株在LB平板上划线,37 ℃培养12 h,挑单菌落于含有5 mL LB液体培养基的试管中,37 ℃、200 r/min振荡培养12 h,以1%的接种量接种于装有50 mL LB液体培养基的三角瓶中,37 ℃、200 r/min振荡培养2-3 h,4 000 r/min离心10 min收集菌体。按照DNA提取试剂盒的说明书提取基因组DNA。使用Illumina HiSeq测序平台对分离获得的大肠杆菌进行全基因组测序,序列使用Velvet软件进行组装。质粒相关的片段进一步通过gap-closing的方法获得完整序列。序列已提交GenBank数据库,登录号分别是VXKY00000000和VXKX00000000。

1.4 耐药基因预测与质粒分析基因组通过NCBI Prokaryotic Genome Annotation Pipeline自动注释。使用ResFinder 3.1数据库[27]对获得性耐药基因进行预测,利用PlasmidFinder 2.0[28]进行质粒复制类型的预测,同源质粒序列比对使用Easyfig[29]和BRIG[30]软件。

1.5 药敏实验使用BiofosunⓇ革兰氏阴性需氧菌药敏板检测大肠杆菌分离株对氨苄西林(ampicillin,AMP)、头孢噻呋(ceftiofur,CEF)、头孢他啶(ceftazidime,CAZ)、奥格门丁(amoxicillin/clavulanate,A/C)、美罗培南(meropenem,MEM)、复方新诺明(trimethoprim/ sulfamethoxazole,SXT)、磺胺异恶唑(sulfisoxazole,SF)、恩诺沙星(enrofloxacin,ENR)、氧氟沙星(ofloxacin,OFL)、四环素(tetracycline,TET)、庆大霉素(gentamicin,GEM)、大观霉素(spectinomycin,SPT)、氟苯尼考(florfenicol,FFC)和粘菌素(colistin,CL) 14种抗生素的最低抑菌浓度(minimal inhibitory concentration,MIC)。以美国临床实验室标准化委员会(clinical and laboratory standards institute of America,CLSI)的标准判断结果[31]。

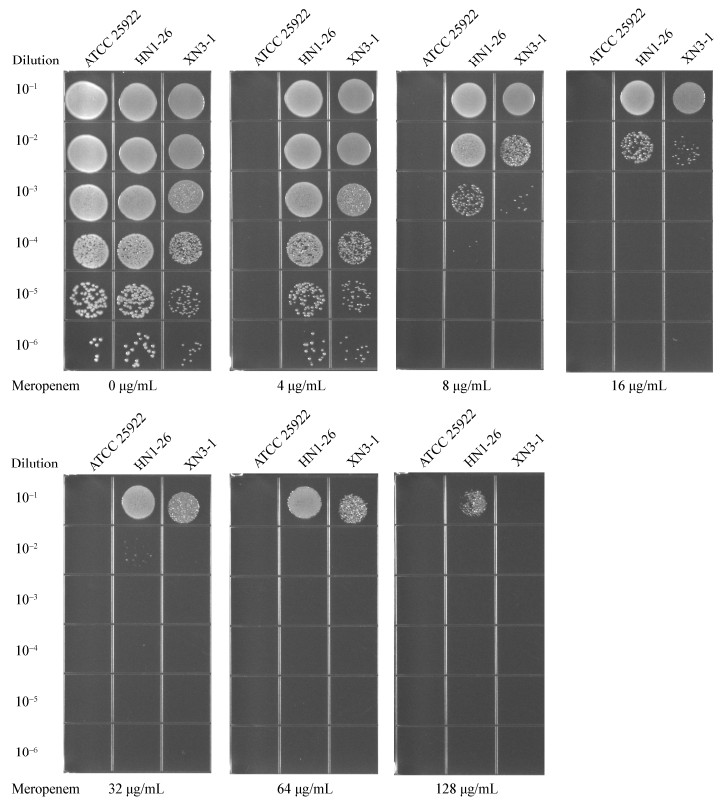

将大肠杆菌分离株使用LB培养基生长到对数期,使用生理盐水配制到麦氏浊度为0.6,按10倍比梯度稀释,得到10-1、10-2、10-3、10-4、10-5、10-6六个梯度的菌悬液,随后以点种的方式接种到美罗培南浓度分别为0、4、8、16、32、64和128 μg/mL的LB方形平板上,测试大肠杆菌分离株在含有不同浓度美罗培南的LB培养基上的生长状态。以大肠杆菌ATCC 25922为对照菌株。

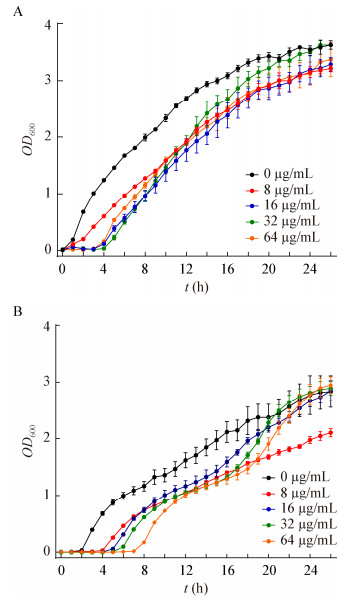

1.6 生长曲线的测定将菌株HN1-26和XN3-1菌株37 ℃培养12 h后,按照1%接种量接种到30 mL LB培养基中,通过微生物自动生长曲线测定仪进行检测。美罗培南浓度分别设置为0、8、16、32和64 μg/mL,实验重复3次。通过测定OD600监测菌体生长浓度,使用GraphPad Prism 8软件绘制生长曲线。

1.7 S1-PAGE、Southern blot与接合转移实验以本次实验分离株为供体菌,利福霉素抗性大肠杆菌EC600菌株作为受体菌。利用Xba Ⅰ酶切标准菌株Salmonella enteric serovar Braenderup H9812作为分子标准,S1核酸酶处理胶块,使用脉冲场电泳系统分离质粒[32]。将地高辛标记的blaNDM-5特异性探针进行Southern blot杂交。接合转移实验具体操作方法参考文献[6]。

2 结果与分析 2.1 菌株鉴定从来自陕西西安的一个鸡养殖场和浙江海宁的两个鸭养殖场中采集的25份粪便样品中分别选择性筛选出8株美罗培南耐药菌株。利用MALDI-TOF MS和16S rRNA基因序列比对后,确定从西安的养殖场筛选出1株大肠杆菌(XN3-1)和1株嗜麦芽寡养单胞菌,从海宁筛选出1株大肠杆菌(HN1-26),2株不动杆菌属和3株紫色杆菌属的菌株。

2.2 药敏实验对两株美罗培南耐药的大肠杆菌进行了药物敏感实验,获得了对14种抗生素的MIC值并进行了对比。如表 1所示,两株菌均表现出多重耐药,其中菌株HN1-26对庆大霉素、氟苯尼考、粘菌素和大观霉素4种抗生素敏感,对头孢他啶、头孢噻呋、氨苄西林、奥格门丁、复方新诺明、磺胺异恶唑、恩诺沙星、氧氟沙星、美罗培南、四环素10种抗生素表现出耐药性,而菌株XN3-1的耐药类型比菌株HN1-26多两种,其对氟苯尼考和大观霉素也表现出耐药性,并且MIC值相差较大,菌株XN3-1对氟苯尼考和大观霉素的MIC分别是 > 256 μg/mL和 > 512 μg/mL,而菌株HN1-26为4 μg/mL和32 μg/mL。

| 抗生素 Antibiotic |

菌株Strains | |

| HN1-26 (μg/mL) |

XN3-1 (μg/mL) |

|

| 氨苄西林Ampicillin (AMP) | > 512* | > 512* |

| 头孢噻呋Ceftiofur (CEF) | 256* | 256* |

| 头孢他啶Ceftazidime (CAZ) | > 256* | > 256* |

| 奥格门丁Amoxicillin/Clavulanate (A/C) | > 512/256* | 64/32* |

| 美罗培南Meropenem (MEM) | 64* | 64* |

| 复方新诺明Trimethoprim/Sulfamethoxazole (SXT) | > 32/608* | > 32/608* |

| 磺胺异恶唑Sulfisoxazole (SF) | > 512* | > 512* |

| 恩诺沙星Enrofloxacin (ENR) | > 32* | 8* |

| 氧氟沙星Ofloxacin (OFL) | 32* | 16* |

| 四环素Tetracycline (TET) | > 512* | > 512* |

| 庆大霉素Gentamicin (GEM) | 0.5 | 1 |

| 大观霉素Spectinomycin (SPT) | 32 | > 512* |

| 氟苯尼考Florfenicol (FFC) | 4 | > 256* |

| 粘杆菌素Colistin (CL) | 0.5 | 0.5 |

| 注:*:判断为耐药. Note: *: Represent antimicrobial resistance. |

||

根据MIC测定,菌株HN1-26和XN3-1对美罗培育的MIC值均为64 μg/mL。进一步测试了菌株HN1-26和XN3-1在美罗培南浓度分别为0、4、8、16、32、64、128 μg/mL的LB平板上的生长活力。从图 1中可以看到,菌株HN1-26耐受性略高于XN3-1,在培养液的稀释度为10-6时,菌株HN1-26在美罗培南浓度为128 μg/mL时仍然可以生长,而菌株XN3-1不生长。同样,从生长曲线(图 2)可得知,菌株HN1-26的生长迟缓期要比菌株XN3-1的短,特别是在美罗培南浓度64 μg/mL时,HN1-26的迟缓期为3 h,而XN3-1的迟缓期为5 h,这与平板检测的稀释点滴图的测试结果类似。实验说明虽然两株菌的对美罗培南的MIC值相同,但在相同抗生素浓度下菌株HN1-26比XN3-1的生长活力高。

|

| 图 1 菌株HN1-26和XN3-1在不同浓度的美罗培南LB平板上的生长状况 Figure 1 The growth of HN1-26 and XN3-1 on LB plates with different meropenem concentration |

|

|

|

| 图 2 菌株HN1-26 (A)和XN3-1 (B)的生长曲线 Figure 2 Growth curves of strains HN1-26 (A) and XN3-1 (B) |

|

|

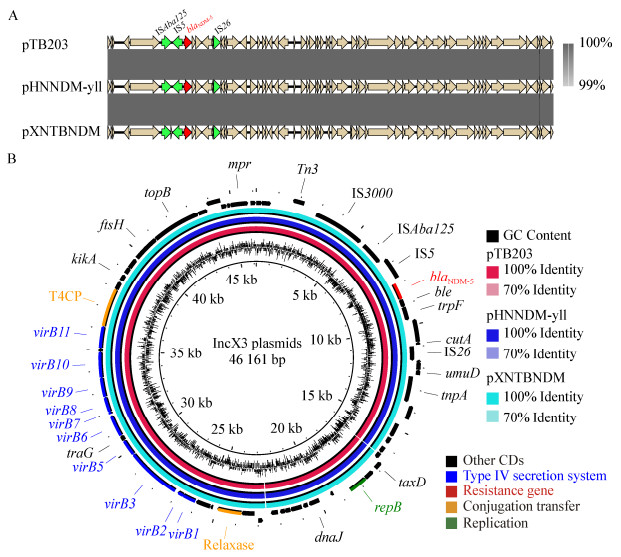

通过S1-PFGE和Southern blot发现,菌株HN1-26和XN3-1存在相同大小的携带blaNDM-5的质粒(图 3),将其命名为pHNNDM-yll和pXNTBNDM。基于全基因组测序的组装结果,获得的这两个质粒的全序列大小为46 161 bp,且序列完全一致。利用ResFinder数据库对测序结果进行了分析,在菌株HN1-26的基因组中预测到10个获得性耐药基因:β-内酰胺类blaNDM-5、blaTEM-1B;氨基糖苷类aph(3′′)-Ib、aph(3′)-Ia、aph(6)-Id;喹诺酮类oqxB;甲氧嘧啶类dfrA17;苯丙醇类catA1;磺胺类sul2;四环素类tet(B);在菌株XN3-1的基因组中预测到16个获得性耐药基因:β-内酰胺类blaNDM-5、blaTEM-1B;氨基糖苷类aadA2、aph(6)-Id、aadA22、aph(3′)-Ia;喹诺酮类qnrS1;甲氧嘧啶类dfrA12、dfrA14;大环内酯类mph(A)、mdf(A)、lnu(F);苯丙醇类catA1、floR;磺胺类sul3;四环素类tet(A) (表 2)。虽然两种菌株对一些抗生素耐药表型相同,但是耐药基因却不同,例如菌株HN1-26对四环素的耐药基因是tet(B),而XN3-1是tet(A)。此外,在HN1-26中预测到了parE (p.I355T)突变、gyrA (p.S83L、p.D87N)双突变和parC (p.S80I、p.E84G)双突变,在XN3-1中只预测到了gyrA (p.S83L)突变,并且这些突变均介导了两株菌对喹诺酮类药物萘啶酸和环丙沙星的抗性。

|

| 图 3 菌株HN1-26和XN3-1的S1-PFGE和Southern blot结果 Figure 3 S1-PFGE and Southern blot results of strains HN1-26 and XN3-1 注:肠炎沙门氏菌血清型Braenderup H9812被用作标记;箭头:含有blaNDM-5基因的质粒. Note: Salmonella enteric serovars Braenderup H9812 was used as a marker; Arrows: The plasmid harboring the blaNDM-5 gene. |

|

|

| 抗生素类型 Antibiotic types |

HN1-26 | XN3-1 | ||||

| Susceptibility | Acquired resistance genes | Susceptibility | Acquired resistance genes | |||

| β-lactam | AMP | R | blaTEM-1B blaNDM-5 |

R | blaTEM-1B blaNDM-5 |

|

| A/C | R | R | ||||

| CEF | R | R | ||||

| CAZ | R | R | ||||

| MEM | R | R | ||||

| Aminoglycoside | GEM | S | aph(6)-Id, aph(3′)-Ia, aph(3′′)-Ib | S | aph(6)-Id, aadA2, aadA22, aph(3′)-Ia | |

| SPT | S | R | ||||

| Colistin | CL | S | S | |||

| Fluoroquinolone | ENR | R | oqxB | S | qnrS1 | |

| OFL | R | R | ||||

| Fosfomycin | ||||||

| MLS-Macrolide, Lincosamide and Streptogramin B | mdf(A) | Inu(F), mph(A), mdf(A) | ||||

| Phenicol | FFC | S | catA1 | R | floR, cmlA1 | |

| Sulfonamides | SF | R | sul2 | R | sul3 | |

| SXT | R | dfrA17 | R | dfrA12, dfrA14 | ||

| Tetracycline | TET | R | tet(B) | R | tet(A) | |

两株菌携带blaNDM-5的质粒通过预测发现是属于IncX3型的质粒,该质粒类型已经广泛分离于世界各地的临床上。多位点序列分型(multilocus sequence typing,MLST)分析[33]将大肠杆菌HN1-26和XN3-1归为ST354和ST10,进一步说明了携带blaNDM-5的大肠杆菌具有种内差异性。与我们先前报道[6]的在浙江蛋鸡中分离的pTB203质粒做比对,差异仅有3个SNP。blaNDM-5基因位于典型的ISAba125-IS5-blaNDM-5-ble-trpF- IS26结构中,与前人报道[23]的一致(图 4A)。质粒具备完整的接合转移元件,包括松弛酶基因、Ⅳ型偶联蛋白编码基因(T4CP)和Ⅳ型细菌分泌系统基因簇(图 4B)。随后对两个质粒接合转移效率进行了测定,结果分别为(2.58±0.14)×10-2和(1.68±0.27)×10-3,证实了菌株HN1-26和XN3-1中携带的blaNDM-5的质粒可以进行种内转移。

|

| 图 4 菌株HN1-26和XN3-1中质粒pHNNDM-yll和pXNTBNDM与pTB203的比较 Figure 4 Comparison of pHNNDM-yll and pXNTBNDM with pTB203 注:外环代表质粒的注释;基因根据功能注释不同的颜色. Note: The external ring represents the annotation of plasmids; The genes are colored differently according to the function annotation. |

|

|

blaNDM-5是分布最普遍的blaNDM基因的变型体之一。目前世界各地已经从不同来源中发现了携带blaNDM-5的质粒,包括临床病人[34]、动物[35]和食品[36]。在中国,该类型质粒同样在各个省流行,人类是blaNDM-5的主要宿主。截至目前,从家禽和家畜中共报道23个含blaNDM-5的IncX3型质粒(表 3),包括2016年从四川的猪中检测到的1个质粒[25],2017年从浙江的蛋鸡中检测到1个质粒[6],2018和2019年分别从江苏的奶牛和鹅中检测到10个质粒[37]和9个质粒[21],2019年从浙江和陕西西安的鸭和鸡粪便中检测到的2个质粒(本研究)。说明该质粒流行性较强,人和动物可以相互传播,另外未分离到的省可能与医疗科研水平、取样少有很大关系。

| 菌株 Stains |

质粒 Plasmids |

长度 Length (bp) |

物种 Species |

宿主 Host |

省 Provinces |

登录号 Accession No. |

文献 References |

| L37 | pL37-2 | 45 650 | Escherichia coli | Goose | Jiangsu | CP034591 | [21] |

| L65 | pL65-2 | 46 161 | Escherichia coli | Goose | Jiangsu | CP034744 | [21] |

| L100 | pL100-2 | 46 261 | Escherichia coli | Goose | Jiangsu | CP034748 | [21] |

| L103-2 | pL103-2-2 | 46 163 | Escherichia coli | Goose | Jiangsu | CP034847 | [21] |

| L33 | Unknown | ~46 000 | Escherichia coli | Goose | Jiangsu | [21] | |

| 1L43-1 | Unknown | ~46 000 | Escherichia coli | Goose | Jiangsu | [21] | |

| L102 | Unknown | ~46 000 | Escherichia coli | Goose | Jiangsu | [21] | |

| L103-1 | Unknown | ~46 000 | Escherichia coli | Goose | Jiangsu | [21] | |

| L99 | Unknown | ~46 000 | Escherichia coli | Goose | Jiangsu | [21] | |

| XG-K3 | Unknown | ~46 000 | Klebsiella pneumoniae | Cow | Jiangsu | [36] | |

| XG-K4 | Unknown | ~46 000 | Klebsiella pneumoniae | Cow | Jiangsu | [36] | |

| XG-K9 | Unknown | ~46 000 | Klebsiella pneumoniae | Cow | Jiangsu | [36] | |

| TQ-K1 | pNDM-Kpn-1 | 46 161 | Klebsiella pneumoniae | Cow | Jiangsu | [36] | |

| TQ-K2 | Unknown | ~46 000 | Klebsiella pneumoniae | Cow | Jiangsu | [36] | |

| TQ-K3 | Unknown | ~46 000 | Klebsiella pneumoniae | Cow | Jiangsu | [36] | |

| TQ-K4 | Unknown | ~46 000 | Klebsiella pneumoniae | Cow | Jiangsu | [36] | |

| K11424 | Unknown | ~46 000 | Klebsiella pneumoniae | Cow | Jiangsu | [36] | |

| K12016 | Unknown | ~46 000 | Klebsiella pneumoniae | Cow | Jiangsu | [36] | |

| YZ-K1 | Unknown | ~46 000 | Klebsiella pneumoniae | Cow | Jiangsu | [36] | |

| Unknown | pECNDM101 | 46 165 | Eshcherichia coli | Swine | Sichuan | KX507346 | [25] |

| ECCRA-119 | pTB203 | 46 161 | Eshcherichia coli | Hen | Zhejiang | CP029245 | [6] |

| HN1-26 | pHNNDM-yll | 46 161 | Eshcherichia coli | Duck | Zhejiang | CM018322 | This study |

| XN3-1 | pXNTBNDM | 46 161 | Eshcherichia coli | Hen | Shaanxi | CM018321 | This study |

重要耐药细菌的流行会影响公共卫生安全,危害人类健康,一直以来都是被人们高度重视的问题。前人已报道了从临床、食品、动物和环境中分离到相同类型的对人类具有威胁的病原菌,如碳青霉烯类或粘菌素耐药的肠杆菌科细菌[38-41]。本次研究从陕西西安和浙江海宁的家禽养殖场中发现了含有blaNDM-5基因的大肠杆菌,序列型分别为ST10和ST354,blaNDM-5基因均由IncX3型质粒携带。根据药物敏感实验的结果显示,菌株HN1-26和XN3-1分别对10种和12种不同的抗生素具有耐药性,并且基本可以从获得性耐药基因和基因组突变得到解释。此次研究中,还证实了菌株HN1-26和XN3-1中携带blaNDM-5的IncX3型质粒具有接合转移的能力,具有传播风险。

值得注意的是,菌株HN1-26和XN3-1的来源和ST型虽然均不相同,但是其所含质粒pHNNDM-yll和pXNTBNDM的序列完全一致,并与已经报道的大肠杆菌分离株EC119的pTB203质粒序列也仅有3个碱基位点的差异,这些结果表明IncX3型质粒是blaNDM-5基因传播的高效载体,且序列高度保守。本文分离的两株大肠杆菌携带blaNDM-5基因的质粒完全一致,对美罗培南的MIC值均为64 μg/mL,但是在进一步在对两株菌进行生长曲线的测定时发现,两株菌对美罗培南表现出细微的抗药性差异,菌株HN1-26相对XN3-1较强。造成这种情况的原因一方面是菌株的遗传背景差异可能造成对blaNDM-5基因的表达强度不同,或者不同菌株自身对美罗培南的抗性程度有一定差异;另一方面也有可能是菌株携带其他耐药基因,对美罗培南的抗性有交叉影响。以上3株菌都是从动物粪便中分离,结合在人群中流行的文献报道[13],表明了携带blaNDM-5基因的IncX3型质粒在中国畜禽养殖中传播的严重性。碳青霉烯类抗生素在动物中禁用,因此相关抗性基因很可能是从人传给动物。遏制耐药性,必须将人、动物和环境作为一个整体考虑,始终坚持One Health理念[42-43],加强养殖动物的碳青霉烯类耐药菌的监测。

| [1] |

Yong D, Toleman MA, Giske CG, et al. Characterization of a new metallo-β-lactamase gene, blaNDM-1, and a novel erythromycin esterase gene carried on a unique genetic structure in Klebsiella pneumoniae sequence type 14 from India[J]. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy, 2009, 53(12): 5046-5054. DOI:10.1128/AAC.00774-09 |

| [2] |

Mai WH, Chen DK, Li J, et al. Isolation and drug-resistant gene analysis of Escherichia coli strain carrying blaNDM-5 in Hainan province, China[J]. Chinese Journal of Clinical Laboratory Science, 2016, 34(5): 354-357. (in Chinese) 麦文慧, 陈东科, 李娟, 等. 海南地区1株携带blaNDM-5大肠埃希氏菌的分离及耐药基因分析[J]. 临床检验杂志, 2016, 34(5): 354-357. DOI:10.13602/j.cnki.jcls.2016.05.11 |

| [3] |

Pál T, Ghazawi A, Darwish D, et al. Characterization of NDM-7 carbapenemase-producing Escherichia coli isolates in the Arabian Peninsula[J]. Microbial Drug Resistance, 2017, 23(7): 871-878. DOI:10.1089/mdr.2016.0216 |

| [4] |

Peirano G, Schreckenberger PC, Pitout JDD. Characteristics of NDM-1-producing Escherichia coli isolates that belong to the successful and virulent clone ST131[J]. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy, 2011, 55(6): 2986-2988. DOI:10.1128/AAC.01763-10 |

| [5] |

Wang B, Sun DC. Detection of NDM-1 carbapenemase-producing Acinetobacter calcoaceticus and Acinetobacter junii in environmental samples from livestock farms[J]. Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy, 2015, 70(2): 611-613. DOI:10.1093/jac/dku405 |

| [6] |

Tang B, Chang J, Cao LJ, et al. Characterization of an NDM-5 carbapenemase-producing Escherichia coli ST156 isolate from a poultry farm in Zhejiang, China[J]. BMC Microbiology, 2019, 19(1): 82. DOI:10.1186/s12866-019-1454-2 |

| [7] |

Hornsey M, Phee L, Wareham DW. A novel variant, NDM-5, of the New Delhi Metallo-β-lactamase in a multidrug-resistant Escherichia coli ST648 isolate recovered from a patient in the United Kingdom[J]. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy, 2011, 55(12): 5952-5954. DOI:10.1128/AAC.05108-11 |

| [8] |

Baek JY, Cho SY, Kim SH, et al. Plasmid analysis of Escherichia coli isolates from South Korea co-producing NDM-5 and OXA-181 carbapenemases[J]. Plasmid, 2019, 104: 102417. DOI:10.1016/j.plasmid.2019.102417 |

| [9] |

Mao JP, Liu WG, Wang W, et al. Antibiotic exposure elicits the emergence of colistin- and carbapenem-resistant Escherichia coli coharboring MCR-1 and NDM-5 in a patient[J]. Virulence, 2018, 9(1): 1001-1007. DOI:10.1080/21505594.2018.1486140 |

| [10] |

Nakano R, Nakano A, Hikosaka K, et al. First report of metallo-β-lactamase NDM-5-producing Escherichia coli in Japan[J]. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy, 2014, 58(12): 7611-7612. DOI:10.1128/AAC.04265-14 |

| [11] |

Rojas LJ, Hujer AM, Rudin SD, et al. NDM-5 and OXA-181 beta-lactamases, a significant threat continues to spread in the Americas[J]. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy, 2017, 61(7): e00454-17. |

| [12] |

Li X, Fu Y, Shen MY, et al. Dissemination of blaNDM-5 gene via an IncX3-type plasmid among non-clonal Escherichia coli in China[J]. Antimicrobial Resistance & Infection Control, 2018, 7: 59. DOI:10.1186/s13756-018-0349-6 |

| [13] |

Shen ZQ, Hu YY, Sun QL, et al. Emerging carriage of NDM-5 and MCR-1 in Escherichia coli from healthy people in multiple regions in China: a cross sectional observational study[J]. EClinicalMedicine, 2018, 6: 11-20. DOI:10.1016/j.eclinm.2018.11.003 |

| [14] |

Wailan AM, Paterson DL, Caffery M, et al. Draft genome sequence of NDM-5-producing Escherichia coli sequence type 648 and genetic context of blaNDM-5 in Australia[J]. Genome Announcements, 2015, 3(2): e00194-15. DOI:10.1128/genomea.00194-15 |

| [15] |

Krishnaraju M, Kamatchi C, Jha AK, et al. Complete sequencing of an IncX3 plasmid carrying blaNDM-5 allele reveals an early stage in the dissemination of the blaNDM gene[J]. Indian Journal of Medical Microbiology, 2015, 33(1): 30-38. DOI:10.4103/0255-0857.148373 |

| [16] |

Hong JS, Song W, Park HM, et al. First detection of new delhi metallo-β-lactamase-5-producing Escherichia coli from companion animals in Korea[J]. Microbial Drug Resistance, 2019, 25(3): 344-349. DOI:10.1089/mdr.2018.0237 |

| [17] |

Sekizuka T, Inamine Y, Segawa T, et al. Characterization of NDM-5-and CTX-M-55-coproducing Escherichia coli GSH8M-2 isolated from the effluent of a wastewater treatment plant in Tokyo Bay[J]. Infection and Drug Resistance, 2019, 12: 2243-2249. DOI:10.2147/IDR.S215273 |

| [18] |

Brinkac LM, White R, D'Souza R, et al. Emergence of New Delhi Metallo-β-lactamase (NDM-5) in Klebsiella quasipneumoniae from neonates in a Nigerian hospital[J]. mSphere, 2019, 4(2): e00685-18. |

| [19] |

Mouftah SF, Pál T, Darwish D, et al. Epidemic IncX3 plasmids spreading carbapenemase genes in the United Arab Emirates and worldwide[J]. Infection and Drug Resistance, 2019, 12: 1729-1742. DOI:10.2147/IDR.S210554 |

| [20] |

Wang ZZ, Li ML, Shen XF, et al. Outbreak of blaNDM-5-harboring Klebsiella pneumoniae ST290 in a tertiary hospital in China[J]. Microbial Drug Resistance, 2019, 25(10): 1443-1448. DOI:10.1089/mdr.2019.0046 |

| [21] |

Liu ZY, Xiao X, Li Y, et al. Emergence of IncX3 plasmid-harboring blaNDM-5 dominated by Escherichia coli ST48 in a goose farm in Jiangsu, China[J]. Frontiers in Microbiology, 2019, 10: 2002. DOI:10.3389/fmicb.2019.02002 |

| [22] |

Zhu YQ, Zhao JY, Xu C, et al. Identification of an NDM-5-producing Escherichia coli sequence type 167 in a Neonatal patient in China[J]. Scientific Reports, 2016, 6: 29934. DOI:10.1038/srep29934 |

| [23] |

Zhang FF, Xie LY, Wang XL, et al. Further spread of blaNDM-5 in Enterobacteriaceae via IncX3 plasmids in Shanghai, China[J]. Frontiers in Microbiology, 2016, 7: 424. |

| [24] |

Liao XP, Yang RS, Xia J, et al. High colonization rate of a novel carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella lineage among migratory birds at Qinghai Lake, China[J]. Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy, 2019, 74(10): 2895-2903. DOI:10.1093/jac/dkz268 |

| [25] |

Kong LH, Lei CW, Ma SZ, et al. Various sequence types of Escherichia coli isolates coharboring blaNDM-5 and mcr-1 genes from a commercial swine farm in China[J]. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy, 2017, 61(3): e02167-16. DOI:10.1128/AAC.02167-16 |

| [26] |

Xu YL, Wang JL, Zhang AM, et al. Rapid detection and identification on 16S rRAN gene of enteropathogentic[J]. Modern Preventive Medicine, 2011, 38(7): 3528-3529. (in Chinese) 许玉玲, 王建丽, 张爱梅, 等. 肠道致病菌16S rRNA基因的快速检测和鉴定[J]. 现代预防医学, 2011, 38(7): 3528-3529. |

| [27] |

Zankari E, Hasman H, Cosentino S, et al. Identification of acquired antimicrobial resistance genes[J]. Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy, 2012, 67(11): 2640-2644. DOI:10.1093/jac/dks261 |

| [28] |

Carattoli A, Zankari E, García-Fernández A, et al. In silico detection and typing of plasmids using PlasmidFinder and plasmid multilocus sequence typing[J]. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy, 2014, 58(7): 3895-3903. DOI:10.1128/AAC.02412-14 |

| [29] |

Sullivan MJ, Petty NK, Beatson SA. Easyfig: a genome comparison visualizer[J]. Bioinformatics, 2011, 27(7): 1009-1010. DOI:10.1093/bioinformatics/btr039 |

| [30] |

Alikhan NF, Petty NK, Zakour NLB, et al. BLAST ring image generator (BRIG): simple prokaryote genome comparisons[J]. BMC Genomics, 2011, 12: 402. DOI:10.1186/1471-2164-12-402 |

| [31] |

Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. CLSI Document M100-S25 Performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing; 25th Informational Supplement[S]. Wayne, PA: Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute, 2015

|

| [32] |

Tang B, Zhang L, Chang J, et al. Antimicrobial resistance of two Escherichia fergusonii strains isolated from chicken feces[J]. Microbiology China, 2019, 46(11): 3022-3029. (in Chinese) 唐标, 张玲, 常江, 等. 两株分离自鸡粪便费格森埃希菌的耐药性[J]. 微生物学通报, 2019, 46(11): 3022-3029. |

| [33] |

Larsen MV, Cosentino S, Rasmussen S, et al. Multilocus sequence typing of total-genome-sequenced bacteria[J]. Journal of Clinical Microbiology, 2012, 50(4): 1355-1361. DOI:10.1128/JCM.06094-11 |

| [34] |

Sassi A, Loucif L, Gupta SK, et al. NDM-5 carbapenemase-encoding gene in multidrug-resistant clinical isolates of Escherichia coli from Algeria[J]. Antimicrobical Agents and Chemotherapy, 2014, 58(9): 5606-5608. DOI:10.1128/AAC.02818-13 |

| [35] |

Tyson GH, Li C, Ceric O, et al. Complete genome sequence of a carbapenem-resistant Escherichia coli isolate with blaNDM-5 from a dog in the United States[J]. Microbiology Resource Announcements, 2019, 8(34): e00872-19. |

| [36] |

Liu BT, Zhang XY, Wan SW, et al. Characteristics of carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae in ready-to-eat vegetables in China[J]. Frontiers in Microbiology, 2018, 9: 1147. DOI:10.3389/fmicb.2018.01147 |

| [37] |

He T, Wang Y, Sun LC, et al. Occurrence and characterization of blaNDM-5-positive Klebsiella pneumoniae isolates from dairy cows in Jiangsu, China[J]. Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy, 2017, 72(1): 90-94. DOI:10.1093/jac/dkw357 |

| [38] |

Gao RS, Hu YF, Li ZC, et al. Dissemination and mechanism for the MCR-1 colistin resistance[J]. PLoS Pathogens, 2016, 12(11): e1005957. DOI:10.1371/journal.ppat.1005957 |

| [39] |

Gao RS, Wang QJ, Li P, et al. Genome sequence and characteristics of plasmid pWH12, a variant of the mcr-1-harbouring plasmid pHNSHP45, from the multi-drug resistant E. coli[J]. Virulence, 2016, 7(6): 732-735. DOI:10.1080/21505594.2016.1193279 |

| [40] |

Liu ZH, Li JY, Wang XM, et al. Corrigendum: novel variant of new delhi metallo-β-lactamase, NDM-20, in Escherichia coli[J]. Frontiers in Microbiology, 2018, 9: 497. DOI:10.3389/fmicb.2018.00497 |

| [41] |

Wang QJ, Sun J, Ding YF, et al. Genomic insights into mcr-1-positive plasmids carried by colistin-resistant Escherichia coli isolates from inpatients[J]. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy, 2017, 61(7): e00361-17. |

| [42] |

Rhouma M, Beaudry F, Thériault W, et al. Colistin in pig production: chemistry, mechanism of antibacterial action, microbial resistance emergence, and One Health perspectives[J]. Frontiers in Microbiology, 2016, 7: 1789. |

| [43] |

Wang XZ, Lin Z, Lu JH, et al. One Health strategy to prevent and control antibiotic resistance[J]. Chinese Journal of Biotechnology, 2018, 34(8): 1361-1367. (in Chinese) 王宣焯, 林震宇, 陆家海, 等. 抗生素耐药防控的One Health策略[J]. 生物工程学报, 2018, 34(8): 1361-1367. |

2020, Vol. 47

2020, Vol. 47