扩展功能

文章信息

- 王家源, 殷小琳, 任悦, 高广磊, 丁国栋, 张英, 赵珮杉, 郭米山

- WANG Jia-Yuan, YIN Xiao-Lin, REN Yue, GAO Guang-Lei, DING Guo-Dong, ZHANG Ying, ZHAO Pei-Shan, GUO Mi-Shan

- 毛乌素沙地樟子松外生菌根真菌多样性特征

- Diversity characteristics of ectomycorrhizal fungi associated with Pinus sylvestris var. mongolica in the Mu Us sandy land

- 微生物学通报, 2020, 47(11): 3856-3867

- Microbiology China, 2020, 47(11): 3856-3867

- DOI: 10.13344/j.microbiol.china.200365

-

文章历史

- 收稿日期: 2020-04-11

- 接受日期: 2020-09-16

- 网络首发日期: 2020-09-21

2. 宁夏盐池毛乌素沙地生态系统国家定位观测研究站 宁夏 盐池 751500;

3. 中国水利水电科学研究院 北京 100038

2. Yanchi Ecology Research Station of the Mu Us Desert, Yanchi, Ningxia 751500, China;

3. China Institute of Water Resource and Hydropower Research, Beijing 100038, China

外生菌根真菌(ectomycorrhizal fungi,ECMF)广泛存在于森林生态系统中,是一种重要的真核微生物类群[1]。ECMF从寄主植物获取生长所需的碳源,其菌丝体可以侵染寄主植物尚未木栓化的营养根形成外生菌根,不仅能够有效促进寄主植物吸收土壤水分和矿物养分,对于提高寄主植物抗逆能力、适应环境变化和环境胁迫及维持森林生态系统稳定性也具有重要意义[2-4]。ECMF具有丰富的物种多样性,其物种组成、分布格局、影响因素和维持机制始终是相关领域研究的焦点和热点问题[5]。在研究早期,ECMF物种鉴定主要依赖于传统的形态学和解剖学方法,其精确性和实用性存在较多问题[6]。近年来,随着遗传学和基因组学的快速发展,高通量测序技术等被广泛应用于生物地理学的物种鉴定工作[7],极大地推动了ECMF多样性研究的发展。据不完全统计,全球范围内已发现的ECMF大概有2万种[8],但由于共生关系的复杂性,仍远低于自然界实际存在的ECMF数量。

松属(Pinus)植物是ECMF的重要寄主,大约3/4的ECMF均可与针叶树种形成外生菌根,而其中超过1/3可与松属植物形成外生菌根[9]。沙地樟子松(Pinus sylvestris var. mongholica)是欧洲赤松(P. sylvestris)在东亚的一个地理变种,原产于呼伦贝尔红花尔基地区,是我国北方风沙区引种种植范围最广的常绿乔木树种[10]。但自20世纪80年代开始,引种栽植的沙地樟子松却出现了大面积的衰退和死亡现象。微生物共生是植物健康和生态系统功能的主要影响之一[11],沙地樟子松是典型的外生菌根依赖型乔木树种,在没有外生菌根的条件下很难生存[12]。目前,沙地樟子松外生菌根研究已多有报道,并取得较为丰硕的研究成果,但主要集中于部分外生菌根与沙地樟子松的互利关系[12-13],而对于ECMF群落组成和多样性研究多在沙地樟子松原产地的人工林和天然林进行,半干旱区引种地的研究仍较为薄弱。具有功能性的ECMF群落组成不是固定的,群落随生存环境和寄主生长周期变化[14-15]。ECMF群落的变化与森林生产力密切相关[16]。松树被引入远离原产地的地区时,自身根部和本地ECMF会产生竞争关系共同侵染根部[17]。引种地的环境条件可能会使原生ECMF失去优势[18],重组后的ECMF群落会与原产地有较大的差异。因此,调查分析引种地ECMF群落组成可能是揭示沙地樟子松引种地衰退和死亡现象的重要途径。

毛乌素沙地是我国四大沙地之一,总面积约为3.2万km2。为治理区域沙化土地,毛乌素地区引种栽植了大量的沙地樟子松苗木,是中国重要的沙地樟子松引种栽植区。林龄是决定ECMF群落多样性和丰富度的重要因素[19],而且樟子松林龄与ECMF子实体产孢关系密切[20],但也有研究显示,林龄对人工林ECMF群落多样性和丰富度没有显著影响[21]。因此,ECMF群落多样性是否能反映樟子松人工林生长情况暂无定论。鉴于此,本研究以毛乌素沙地不同年代引种栽植的沙地樟子松人工林为研究对象,利用分子生物学技术研究不同林龄沙地樟子松的ECMF多样性和群落组成,探究林龄对ECMF多样性和群落组成的影响,而且假设林龄会显著影响沙地樟子松ECMF群落多样性,以期为沙地樟子松经营管理提供理论依据和科技支撑。

1 材料与方法 1.1 研究区概况研究区位于陕西省榆林市红石峡沙生植物园,地处毛乌素沙地东南部(38°19′49″N− 38°20′12″,109°42′08″−109°42′55″E),海拔1.1 km。该区属暖温带半干旱大陆性季风气候,光照充足,昼夜温差大。年均气温6.0−8.5 ℃,年均无霜期150 d左右,年均降水量385 mm,降雨分配不均,年均蒸发量2 914 mm。研究区主要土壤类型是非地带性风沙土,其机械组成以砂粒为主,结构松散,养分含量较低。研究区主要乔木树种为沙地樟子松和油松(Pinus tabuliformis)等,主要灌草植物包括油蒿(Artemisia ordosica)、铁杆蒿(A. gmelinii)、鬼针草(Bidens pilosa)、蒙古冰草(Agropyon oristatum)和蒺藜(Tribulus terrestris)等[22]。

1.2 主要试剂和仪器PowerSoil® DNA试剂盒,MO BIO公司;AxyPrepDNA凝胶试剂盒,Axygen公司。PCR仪,ABI公司;MiseqPE300测序仪,Illumina公司。

1.3 样品采集与处理2018年7月,在植物生长旺盛期,结合森林清查数据和实地踏勘,在陕西省榆林市红石峡沙生植物园选择27、33和44 a沙地樟子松人工林布设研究样地(表 1),这3个林分分别处于中龄林、近熟林、成熟林的典型发育阶段。每种林龄林分内布设1块50×50 m样方,每木检尺后,每种林分内选取间距10 m以上的5棵长势均一、无病虫害的沙地樟子松标准木作为采样对象。先用铁锹除去林木基部半径1−2 m内的地表覆盖物,小心掘取根样并注意挖至根的末级,剔除杂草等其他植物根系。每棵标准木取3个重复,并将3个重复混合成一个细根样品装入塑封袋中(注意携带少量土壤用于根系保鲜)并编号,共15份样品立刻置于−4 ℃便携式保温箱保存,并于72 h内带回实验室,根样保存在−80 ℃冰箱中以备后用。

| 样地 Plot |

林龄Age (a) |

平均树高 Average height (m) |

平均胸径 Average DBH (cm) |

林分密度 Stand density (N/hm2) |

郁闭度 Canopy density |

| Ⅰ | 27 | 12.72±2.56 | 12.54±2.48 | 2 500 | 0.82 |

| Ⅱ | 33 | 14.06±2.08 | 14.21±2.85 | 2 500 | 0.86 |

| Ⅲ | 44 | 14.21±2.54 | 20.34±3.12 | 1 650 | 0.72 |

轻轻地取出细根样品,并用蒸馏水小心清洗其表面土壤颗粒和杂物,清洗干净后将细根剪成10 cm的根段,置于盛有蒸馏水的培养皿中。将每个样地中5棵树(共15份样品)根尖端末级根剪下后,加入液氮在研钵中研磨处理破碎DNA,按照说明书中的步骤用PowerSoil® DNA试剂盒对样品中的DNA进行提取。利用琼脂糖(质量分数1%)凝胶电泳检测抽提的基因组DNA[23]。采用真菌通用引物ITS1 (5′-TCCGTAG GTGAACCTGCGG-3′)和ITS2 (5′-GCTGCGTTCT TCATCGATGC-3′)进行菌根rDNA ITS区段的PCR扩增。PCR反应条件:95 ℃ 5 min;95 ℃ 45 s,55 ℃ 50 s,72 ℃ 45 s,28个循环;72 ℃ 10 min。PCR反应体系(25 μL):KAPA 2G Robust HotStart ReadyMix 12.5 μL,引物ITS1 (5 μmol/L) 1 μL,引物ITS2 (5 μmol/L) 1 μL,模板DNA 5 μL (30 ng),ddH2O补足至25 μL。混合PCR产物后,采用琼脂糖(质量分数2%)凝胶电泳检测,选用AxyPrepDNA凝胶试剂盒切胶回收PCR产物,采用Tris-HCl缓冲液(0.05 mol/L,25 ℃)洗脱后,使用琼脂糖(质量分数2%)电泳检测。检测合格的PCR产物用于Miseq上机测序。测序工作由北京奥维森生物科技有限公司协助完成。

采用FUNGuild平台(http://www.stbates.org/guilds/app.php)过滤非ECMF的OTU[24]。基于NCBI数据库,采用BLAST方法对比分析OTU代表序列。若对比相似率≥97%则可鉴定到种水平,若相似率为90%−97%则可鉴定到属水平[25]。

1.5 数据处理与分析采用R-3.6.3中Vegan模块计算沙地樟子松ECMF的α多样性指数,包括丰富度指数(S)、Simpson优势度指数(D)、Shannon多样性指数(H)和Pielou均匀度指数(J);计算β多样性指数中的Jaccard (Cj)和Sørenson相似性系数(Cs);完成ECMF群落非度量多维标度(nonmetric multidimensional scaling,NMDS)分析。采用SPSS 20对α多样性指数进行单因素方差分析,置信水平0.05。

2 结果与分析 2.1 沙地樟子松ECMF群落组成毛乌素沙地樟子松根尖样品利用Illumina MiSeq平台测序,共获得高质量ITS序列362 320条,归为1 320个OTU。经过FUNGuild平台鉴定OTU功能型,其中84个OTU属于ECMF。基于NCBI网站GenBank的BLAST进行比对分析,共有56个OTU可鉴定到属及以下水平,并将OTU序列基本信息上传至NCBI数据库。

ECMF OTU包括担子菌门47种和子囊菌门9种,分属于2门3纲8目15科21属(表 2)。Venn图显示,3个林龄有44个共有OTU,种群相对多度前三的OTU为OTU22 (Tomentella sp.)、OTU5 (Geopora pinyonensis)和OTU8 (Tuber beyerlei),分别为13.66%、13.24%和11.06% (图 1)。在56个OTU中,35个OTU被精确鉴定到种水平,包括:丝盖伞属(Inocybe) 6种,地孔菌属(Geopora)和丝膜菌属(Cortinarius)各4种,棉革菌属(Tomentella)、须腹菌属(Rhizopogon)和Mallocybe各3种,红菇属(Russula) 2种,枝瑚菌属(Ramaria)、乳菇属(Lactarius)、块菌属(Tuber)、威氏盘菌属(Wilcoxina)、粘滑菇属(Hebeloma)、乳牛肝菌属(Suillus)、假基块菌属(Genabea)、隔担耳属(Septobasidium)、硬皮马勃属(Scleroderma)和Pseudosperma各1种,其余均鉴定到属水平。

| ECM 编号ECM No. |

GenBank 登录号GenBank accession No. |

序列长度 Sequence length (bp) |

相近菌种 Nearest type strain (accession No.) |

相似性 Similarity (%) |

分类 Classified |

| 1 | MT229554 | 249 | Amphinema sp. (MK342039) | 100 | Amphinema sp. |

| 2 | MT229555 | 257 | Amphinema sp. (MK659788) | 99 | Amphinema sp. |

| 3 | MT229556 | 238 | Cortinarius casimiri (MN947386) | 100 | Cortinarius casimiri |

| 4 | MT229557 | 241 | Cortinarius hemitrichus (DQ097870) | 100 | Cortinarius hemitrichus |

| 5 | MT229558 | 248 | Cortinarius hinnuleus (HQ604704) | 100 | Cortinarius hinnuleus |

| 6 | MT229559 | 319 | Cortinarius spilomeus (KY657257) | 99 | Cortinarius spilomeus |

| 7 | MT229560 | 249 | Delastria sp. (MG367350) | 91 | Delastria sp. |

| 8 | MT229561 | 241 | Genabea fragilis (KX905050) | 100 | Genabea fragilis |

| 9 | MT229562 | 284 | Geopora arenicola (MH366763) | 100 | Geopora arenicola |

| 10 | MT229563 | 300 | Geopora arenicola (MH366763) | 95 | Geopora arenicola |

| 11 | MT229564 | 290 | Geopora pinyonensis (MK841899) | 99 | Geopora pinyonensis |

| 12 | MT229565 | 293 | Geopora pinyonensis (MK841900) | 99 | Geopora pinyonensis |

| 13 | MT229566 | 296 | Geopora sp. (MK342047) | 100 | Geopora sp. |

| 14 | MT229567 | 316 | Hebeloma dunense (KX687199) | 99 | Hebeloma dunense |

| 15 | MT229568 | 231 | Hygrophorus sp. STDS-2-40 (LC098766) | 100 | Hygrophorus sp. STDS-2-40 |

| 16 | MT229569 | 359 | Inocybe cf. squarrosoannulata CLC1490 (GU980612) | 95 | Inocybe cf. squarrosoannulata |

| 17 | MT229570 | 297 | Inocybe decipiens (MK342092) | 100 | Inocybe decipiens |

| 18 | MT229571 | 297 | Inocybe dunensis (MK659791) | 100 | Inocybe dunensis |

| 19 | MT229572 | 243 | Inocybe jacobi (HQ604813) | 99 | Inocybe jacobi |

| 20 | MT229573 | 360 | Inocybe siciliana (NR164583) | 99 | Inocybe siciliana |

| 21 | MT229574 | 340 | Inocybe sp. (MK342051) | 100 | Inocybe sp. |

| 22 | MT229575 | 332 | Inocybe subporospora (KX602276) | 99 | Inocybe subporospora |

| 23 | MT229576 | 289 | Lactarius lapponicus (KX394291) | 100 | Lactarius lapponicus |

| 24 | MT229577 | 364 | Mallocybe aff. agardhii CM080 (KP826754) | 98 | Mallocybe aff. agardhii CM080 |

| 25 | MT229578 | 359 | Mallocybe umbrinofusca (GU980613) | 97 | Mallocybe umbrinofusca |

| 26 | MT229579 | 349 | Mallocybe umbrinofusca (GU980613) | 94 | Mallocybe umbrinofusca |

| 27 | MT229580 | 332 | Pseudosperma cf. rimosum (MK342036) | 100 | Pseudosperma cf. rimosum |

| 28 | MT229581 | 287 | Ramaria abietina (MK342055) | 100 | Ramaria abietina |

| 29 | MT229582 | 298 | Rhizopogon jiyaozi (KP893833) | 100 | Rhizopogon jiyaozi |

| 30 | MT229583 | 299 | Rhizopogon mohelnensis (MH366771) | 100 | Rhizopogon mohelnensis |

| 31 | MT229584 | 297 | Rhizopogon mohelnensis (MK342033) | 100 | Rhizopogon mohelnensis |

| 32 | MT229585 | 261 | Russula nitida (KT934001) | 99 | Russula nitida |

| 33 | MT229586 | 261 | Russula paludosa (MN947359) | 100 | Russula paludosa |

| 34 | MT229587 | 276 | Russula sp. MB-2014 (KP056303) | 100 | Russula sp. MB-2014 |

| 35 | MT229588 | 240 | Scleroderma citrinum (HM237176) | 100 | Scleroderma citrinum |

| 36 | MT229589 | 195 | Septobasidium sinuosum (DQ241463) | 93 | Septobasidium sinuosum |

| 37 | MT229590 | 290 | Suillus pictus (JN021099) | 100 | Suillus pictus |

| 38 | MT229591 | 276 | Tomentella badia (JQ711882) | 99 | Tomentella badia |

| 39 | MT229592 | 277 | Tomentella pilosa (MK342058) | 100 | Tomentella pilosa |

| 40 | MT229593 | 275 | Tomentella sp. ‘LT56’ (U83482) | 99 | Tomentella sp.4 |

| 41 | MT229594 | 276 | Tomentella sp. (KT353056) | 99 | Tomentella sp.3 |

| 42 | MT229595 | 273 | Tomentella sp. (KX438355) | 100 | Tomentella sp.2 |

| 43 | MT229596 | 275 | Tomentella sp. (MK342038) | 100 | Tomentella sp.1 |

| 44 | MT229597 | 274 | Tomentella sublilacina (KP783476) | 100 | Tomentella sublilacina |

| 45 | MT229598 | 173 | Tuber beyerlei (MK342037) | 100 | Tuber beyerlei |

| 46 | MT229599 | 305 | Uncultured Lactarius (KC455337) | 100 | Lactarius sp. |

| 47 | MT229600 | 259 | Uncultured Russula (KU176270) | 100 | Russula sp. |

| 48 | MT229601 | 279 | Uncultured Tomentella (FJ554299) | 100 | Tomentella sp.5 |

| 49 | MT229602 | 279 | Uncultured Tomentella (KU176245) | 99 | Tomentella sp.6 |

| 50 | MT229603 | 275 | Uncultured Tomentella (KY574410) | 99 | Tomentella sp.10 |

| 51 | MT229604 | 275 | Uncultured Tomentella (LC013826) | 99 | Tomentella sp.8 |

| 52 | MT229605 | 276 | Uncultured Tomentella (LC013858) | 100 | Tomentella sp.9 |

| 53 | MT229606 | 275 | Uncultured Tomentella (LC013869) | 100 | Tomentella sp.7 |

| 54 | MT229607 | 275 | Uncultured Tomentella (LC013869) | 100 | Tomentella sp.7 |

| 55 | MT229608 | 288 | Uncultured Tomentellopsis (JQ177145) | 99 | Tomentellopsis sp. |

| 56 | MT229609 | 264 | Wilcoxina rehmii (MH366752) | 100 | Wilcoxina rehmii |

|

| 图 1 毛乌素沙地樟子松ECMF韦恩分析(OTU水平) Figure 1 Venn diagram of ectomycorrhizal fungi associated with P. sylvestris in the Mu Us Sandy Land (OTU level) 注:Ⅰ:27 a人工林;Ⅱ:33 a人工林;Ⅲ:44 a人工林.下同. Note: Ⅰ: 27 years old; Ⅱ: 33 years old; Ⅲ: 44 years old. The same below. |

|

|

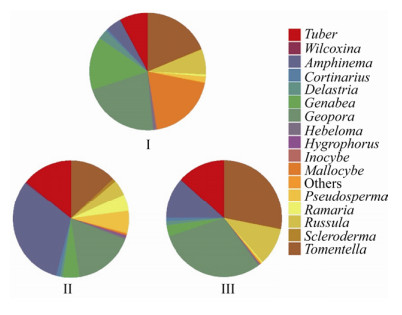

研究区沙地樟子松人工林优势属为棉革菌属、地孔菌属和阿太菌属(Amphinema) (图 2),27、33和44 a人工林ECMF分别有19、20和20个属,不同林龄优势属存在差异。其中,27 a人工林缺失Hygrophorus和威氏盘菌属,优势属为地孔菌属、棉革菌属和Mallocybe,种群相对多度分别为21.41%、19.18%和18.69%;33 a人工林缺失须腹菌属,优势属为阿太菌属、地孔菌属和块菌属,相对多度分别为31.41%、16.88%和14.05%;44 a人工林缺失Mallocybe,优势属为地孔菌属、棉革菌属和块菌属,相对多度分别为30.08%、27.97%和13.39%。

|

| 图 2 毛乌素沙地樟子松ECMF种群相对多度(属水平) Figure 2 Relative abundance of ectomycorrhizal fungi associated with P. sylvestris in the Mu Us Sandy Land (genera level) 注:相对多度小于0.1%的真菌属计为“Others”. Note: Genus with a relative abundance < 0.1% was counted as "Others". |

|

|

毛乌素沙地不同林龄沙地樟子松ECMF丰富度指数较为接近,不同林龄之间不存在显著差异(P > 0.05),不同林龄之间的α多样性指数也不存在显著差异(P > 0.05)。33 a人工林ECMF的Simpson优势度指数、Shannon多样性指数和Pielou均匀度指数均最大,多样性最高,分布最均匀(表 3)。

| Plot | Richness | Shannon | Simpson | Pielou |

| Ⅰ | 38±2.64a | 3.12±0.63a | 0.79±0.10a | 0.59±0.12a |

| Ⅱ | 37±3.85a | 3.39±0.44a | 0.85±0.05a | 0.65±0.07a |

| Ⅲ | 37±3.63a | 2.98±0.64a | 0.79±0.13a | 0.57±0.10a |

| 注:表中同列相同小写字母代表不同林龄样地间不存在显著差异(P > 0.05,n=5). Notes: Same lowercase letter in different plots indicates nonsignificant difference (P > 0.05, n=5). |

||||

毛乌素沙地樟子松33 a与44 a人工林的ECMF Jaccard和Sørenson相似性指数最大,分别是0.87和0.93,说明33 a与44 a人工林的ECMF群落组成最为相似(表 4);27 a与33 a人工林的相似性指数次之,而且和27 a与44 a人工林相似性指数差异不大;27 a与44 a人工林的相似性指数最小,Jaccard和Sørenson相似性指数仅为0.73和0.85,说明27 a与44 a人工林的ECMF群落组成差异较大。不同龄组之间并未出现跨越式相似,处于中间的33 a与44 a人工林更为相似。

| Jaccard (Sørenson) | Ⅰ | Ⅱ |

| Ⅱ | 0.75 (0.86) | |

| Ⅲ | 0.73 (0.85) | 0.87 (0.93) |

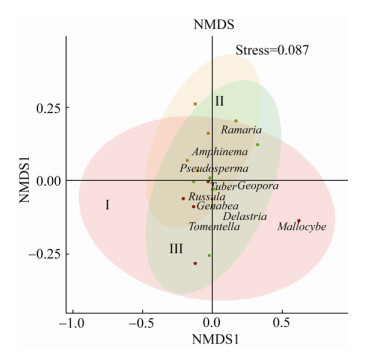

采用NMDS计算毛乌素沙地樟子松人工林ECMF群落组成Bray-curtis距离并进行排序,应力函数值(Stress)为0.087 4 (< 0.2),说明NMDS模型的拟合度较好,Bray-curtis距离能够较好地反映ECMF群落组成差异性(图 3)。

|

| 图 3 毛乌素沙地樟子松ECMF群落NMDS分析(属水平) Figure 3 NMDS analysis of ectomycorrhizal fungal community composition associated with P. sylvestris in the Mu Us Sandy Land (Genera level) 注:图中只标注相对多度Top 10属物种;红色点代表 27 a人工林样点;橘色点代表 33 a人工林样点;绿色点代表 44 a人工林样点;置信椭圆代表不同林龄样点的置信区域(α=0.05),椭圆的长短直径表示位置坐标分量的标准差. Note: Only Top10 relative abundance species genus was labeled; red dots: 27 years old; orange dots: 33 years old; green dots: 44 years old; confidence ellipse represent confidence region in different plots (α=0.05), long and short diameters represent the SD of position coordinate components. |

|

|

由毛乌素沙地不同林龄样地样点坐标分布可知,不同林龄沙地樟子松ECMF群落组成存在差异。由不同林龄置信椭圆的大小可知,随林龄的增加,同一样地的样点之间群落组成相似性越高;由不同林龄置信椭圆的整体分布可知,毛乌素沙地樟子松33 a与44 a人工林ECMF群落组成差异较小,这与相似性指数的结果一致。27 a与33 a人工林样地中各有2个样点与样地内其他样点距离相对较远,表明沙地樟子松27 a与33 a人工林ECMF群落组成存在变异性。由研究区ECMF相对多度Top 10属投影在不同林龄置信椭圆的分布可知,Mallocybe是造成27 a与33 a人工林ECMF群落组成差异的主要原因;地孔菌属、棉革菌属和Delastria是造成33 a和44 a人工林ECMF群落组成差异的主要原因;地孔菌属、棉革菌属、Delastria和Mallocybe是造成27 a与44 a人工林ECMF群落组成差异的主要原因。

3 讨论与结论 3.1 沙地樟子松ECMF群落组成毛乌素沙地樟子松ECMF主要隶属于担子菌门(84%),其次为子囊菌门,与前人对美国黑杨(Populus deltoides)、油松等典型ECMF依赖型树种的研究结果一致[26-27],体现了担子菌门真菌在森林土壤中的优势地位和重要作用[28]。Guo等[10]研究表明,科尔沁沙地樟子松ECMF主要隶属于子囊菌门,这是由于子囊菌门的威氏盘菌属占据优势地位。本研究中也发现了威氏盘菌属,但其种群相对多度不高。

毛乌素沙地樟子松ECMF群落优势属为棉革菌属、地孔菌属和阿太菌属,均为松科(Pinaceae)植物常见菌根菌属[29-30]。棉革菌属真菌为针叶林常见优势菌种[31],也可广泛地与松科、杨柳科(Salicaceae)和半日花科(Cistaceae)植物根系形成外生菌根[32]。地孔菌属则通常在激烈竞争和干旱环境中占优势地位,而且侵染松科树木后可提高树木的生长速度[33]。阿太菌属是秦岭和内蒙古东南部地区华北落叶松(Larix gmelinii) ECMF的优势属[34-35],也是典型的低氮环境优势种且易受土壤扰动影响[36]。沙地樟子松土壤贮存养分的能力较差,沙地的土壤含氮量低于全国N平均水平[22],因此,阿太菌属可在呼伦贝尔沙地樟子松天然林和科尔沁沙地子松人工林中定殖[10, 21]。此外,本研究发现的块菌属和红菇属等也是沙地樟子松林内常见的ECMF类型[37]。枝瑚菌属和Mallocybe首次被发现于毛乌素沙地,乳牛肝菌属是对针叶树种具有较高侵染特异性的外生菌根真菌,属于子实体较大的菌种,在呼伦贝尔沙地天然林和人工林均作为优势菌种广泛分布[21],而在毛乌素沙地种群相对多度较小,这很可能是缺水环境更适合子实体较小的低等真菌定殖[38]。

3.2 沙地樟子松ECMF多样性ECMF群落多样性是衡量外生菌根与寄主共生关系的重要指标,主要受寄主类型和土壤环境的影响[39]。与呼伦贝尔沙地和科尔沁沙地樟子松人工林相比,毛乌素沙地樟子松人工林ECMF群落α多样性指数处于较高水平,甚至高于呼伦贝尔地区天然林[10, 21],因此,这符合不同地区ECMF群落具有明显差异的研究结论[40],同时表明毛乌素沙地樟子松ECMF群落多样性较高且分布更均匀。毛乌素沙地樟子松33 a人工林α多样性指数最高,与呼伦贝尔沙地(33 a人工林)一致[21]。人工林ECMF多样性变化极可能与寄主细根生长状况随林龄的变化规律有关[41]。研究显示樟子松近熟阶段细根根长密度更高、面积更大,以便吸收更多的营养物质和水分以供给植物生长发育[42],细根的变化为ECMF提供了更多生存空间和生态位,然而成熟阶段的树木通常生长缓慢,所需水分和养分有所减少[43],此时无需更多的ECMF与之形成共生体来促进生长。

毛乌素沙地樟子松多样性指数在不同林龄不存在显著差异(P > 0.05),这与前人关于林龄和真菌多样性的研究一致[21, 44-46]。这是因为真菌演替是个复杂且不可预测的过程,环境因素对真菌多样性的影响取决于生态系统的规模和类别,而且真菌多样性在某些生态系统中对环境差异具有相对稳定性[47],寄主植物类型及多样性是真菌多样性的主要驱动因素[46]。由于沙地樟子松人工林林分结构比较简单,缺少其他植被-菌根共生关系的干扰,同一寄主类型不同林龄真菌多样性不会发生较大的变化;竞争是构建ECMF群落组成的重要因素,相同生态位的ECMF会因为寄主的需求改变而产生替代或失去优势地位[48],因此,不同林龄的ECMF群落组成会存在一定的种类及相对多度差异,而多样性不存在显著差异的现象。在本研究中,群落组成可能比多样性更能体现ECMF群落动态变化及寄主的生长情况,竞争使多样性指数无法有效反映不同林龄的情况。

3.3 沙地樟子松ECMF群落组成特征毛乌素沙地樟子松ECMF群落组成没有出现跨越式相似,这与呼伦贝尔沙地和科尔沁沙地的规律一致[10, 21]。毛乌素沙地樟子松33 a与44 a人工林ECMF群落组成最相似,而呼伦贝尔沙地和科尔沁沙地则是27 a与33 a人工林相似程度最高,生态因子是改变ECMF群落组成的重要因素[40],在同一寄主的前提下,气候变化、地理条件和土壤性质会极大地影响ECMF群落与寄主的互相选择。因此,气候和土壤环境的差异,导致不同地区沙地樟子松ECMF群落的演替规律不同[49],从而导致群落组成变化存在较大差异。毛乌素沙地樟子松27 a和33 a人工林ECMF群落组成存在明显的变异性,这与呼伦贝尔沙地和科尔沁沙地的结果不同。呼伦贝尔沙地33 a人工林变异性最低,科尔沁沙地则是26 a人工林[10, 21],这说明沙地樟子松人工林ECMF群落组成符合中性理论[50],空间分布格局存在随机性,而且受地理距离的影响较大。

毛乌素沙地樟子松ECMF相对多度前10个属在各个林龄均有分布,随林龄的增加,前10个属在各个林龄占优势地位的属在逐渐减少。ECMF与寄主存在互相选择的动态关系,随着生态系统演替趋于稳定,最初定殖在寄主植物上的“早期真菌”被后来定殖在植物上的“晚期真菌”所取代[51],生态环境的改变对优势属有一定的筛选作用。相对多度前10个属的Bray-curtis距离坐标表明,块菌属、地孔菌属、红菇属、假基块菌属和Pseudosperma的环境适应性较高,与寄主的共生关系最稳定。Mallocybe是造成27 a人工林与其他林龄ECMF群落组成差异的主要原因,Mallocybe曾在北美和欧洲高寒地区被发现[52],而且分布在我国云南省、吉林省和甘肃省[53]。本研究中首次发现Mallocybe与沙地樟子松的共生关系,目前Mallocybe对寄主的特性有待进一步研究。种群竞争也是造成ECMF群落组成的重要因素[54],在不同沙地樟子松ECMF的相关研究中,子囊菌门的部分属在不同林龄会出现相对多度的明显差异,这种由于环境改变导致的竞争行为可能会破坏ECMF群落与寄主的共生关系平衡,进一步导致帮助樟子松抵御不良环境和生长发育的ECMF失去优势地位,从而影响寄主的生产力和健康状况。隶属于子囊菌门的地孔菌属、棉革菌属和Delastria是造成近熟林与成熟林群落组成差异的主要原因。地孔菌属可以增强寄主对环境胁迫的抵抗性,通常出现在干旱和碱性环境下[55];棉革菌具有腐生功能,能够通过改变自身的生存策略适应变化的环境和植物组织死亡[47],樟子松成熟之后枯落物层的积累使得棉革菌属发挥腐生功能来维持生理活动。Delastria在国内鲜有报道,主要分布于欧洲和非洲等地区[56],Delastria隶属的盘菌科(Pezizaceae)通常出现在酸性环境下,而且盘菌科也是典型的具有潜在腐生能力的ECMF[57]。潜在腐生能力真菌增加的原因可能是由于枯落物层的增加所致,更加丰富的枯落物层为具有腐生潜力的真菌提供了理想的生存环境。同时,枯落物也会对没有腐生潜力的ECMF群落造成不利影响[57]。

值得注意的是,毛乌素沙地樟子松人工林主要在接近成熟时于演替过程中出现退化现象[47],ECMF群落具有潜在腐生能力的优势属相对多度增加的现象也主要存在于这个阶段,如果基于外部环境变化和内部种群竞争下的群落演替导致功能性ECMF群落改变,腐生真菌或具有潜在腐生功能的ECMF占据优势地位[58],可能会改变沙地樟子松对某种必需元素的摄取和枯梢病的抵御能力;同时,该阶段具有抗干旱和盐碱的地孔菌属相对多度增加,说明在该阶段毛乌素沙地樟子松可能正面临更严峻的环境胁迫。总而言之,ECMF对寄主的养分循环和抗逆抗病能力都有着极其重要的意义[59],ECMF群落组成的改变反馈出生态环境和共生功能的变化,而ECMF的功能对沙地樟子松的生命过程有着重要的意义,毛乌素沙地樟子松接近成熟时的群落组成变化可能与人工林退化存在联系。因此,未来应密切关注ECMF优势菌属的功能组成机制及其对沙地樟子松退化的驱动潜力,并注意ECMF群落组成对环境变化的反馈。

| [1] |

Guo LD. Progress of microbial species diversity research in China[J]. Biodiversity Science, 2012, 20(5): 572-580. (in Chinese) 郭良栋. 中国微生物物种多样性研究进展[J]. 生物多样性, 2012, 20(5): 572-580. |

| [2] |

Cheeke TE, Phillips RP, Brzostek ER, et al. Dominant mycorrhizal association of trees alters carbon and nutrient cycling by selecting for microbial groups with distinct enzyme function[J]. New Phytologist, 2017, 214(1): 432-442. DOI:10.1111/nph.14343 |

| [3] |

Köhler J, Yang N, Pena R, et al. Ectomycorrhizal fungal diversity increases phosphorus uptake efficiency of European beech[J]. New Phytologist, 2018, 220(4): 1200-1210. DOI:10.1111/nph.15208 |

| [4] |

Qi JY, Deng JF, Yin DC, et al. Effects of inoculation of exogenous mycorrhizal fungi on the antioxidant and root configuration enzyme activity of Pinus tabulaeformis seedlings[J]. Acta Ecologica Sinica, 2019, 39(8): 2826-2832. (in Chinese) 祁金玉, 邓继峰, 尹大川, 等. 外生菌根菌对油松幼苗抗氧化酶活性及根系构型的影响[J]. 生态学报, 2019, 39(8): 2826-2832. |

| [5] |

Gao C, Guo LD. Distribution pattern and maintenance of ectomycorrhizal fungus diversity[J]. Biodiversity Science, 2013, 21(4): 488-498. (in Chinese) 高程, 郭良栋. 外生菌根真菌多样性的分布格局与维持机制研究进展[J]. 生物多样性, 2013, 21(4): 488-498. |

| [6] |

Agerer R. Fungal relationships and structural identity of their ectomycorrhizae[J]. Mycological Progress, 2006, 5(2): 67-107. DOI:10.1007/s11557-006-0505-x |

| [7] |

Johnson JS, Gaddis KD, Cairns DM, et al. Plant responses to global change: next generation biogeography[J]. Physical Geography, 2016, 37(2): 93-119. DOI:10.1080/02723646.2016.1162597 |

| [8] |

van der Heijden MGA, Martin FM, Selosse MA, et al. Mycorrhizal ecology and evolution: the past, the present, and the future[J]. New Phytologist, 2015, 205(4): 1406-1423. DOI:10.1111/nph.13288 |

| [9] |

Zhang HQ, Yu HX, Tang M. Prior contact of Pinus tabulaeformis with ectomycorrhizal fungi increases plant growth and survival from damping-off[J]. New Forests, 2017, 48(6): 855-866. DOI:10.1007/s11056-017-9601-9 |

| [10] |

Guo MS, Ding GD, Gao GL, et al. Community composition of ectomycorrhizal fungi associated with Pinus sylvestris var. mongolica plantations of various ages in the Horqin Sandy Land[J]. Ecological Indicators, 2020, 110: 105860. DOI:10.1016/j.ecolind.2019.105860 |

| [11] |

van der Heijden MGA, Bardgett RD, van Straalen NM. The unseen majority: soil microbes as drivers of plant diversity and productivity in terrestrial ecosystems[J]. Ecology Letters, 2008, 11(3): 296-310. DOI:10.1111/j.1461-0248.2007.01139.x |

| [12] |

Zhu JJ, Kang HZ, Xu ML, et al. Effects of ectomycorrhizal fungi on alleviating the decline of Pinus sylvestris var. mongolica plantations on Keerqin sandy land[J]. Chinese Journal of Applied Ecology, 2007, 18(12): 2693-2698. (in Chinese) 朱教君, 康宏樟, 许美玲, 等. 外生菌根真菌对科尔沁沙地樟子松人工林衰退的影响[J]. 应用生态学报, 2007, 18(12): 2693-2698. |

| [13] |

Zheng WS, Morris EK, Rillig MC. Ectomycorrhizal fungi in association with Pinus sylvestris seedlings promote soil aggregation and soil water repellency[J]. Soil Biology and Biochemistry, 2014, 78: 326-331. DOI:10.1016/j.soilbio.2014.07.015 |

| [14] |

Diedhiou AG, Dupouey JL, Buée M, et al. The functional structure of ectomycorrhizal communities in an oak forest in central France witnesses ancient Gallo-Roman farming practices[J]. Soil Biology and Biochemistry, 2010, 42(5): 860-862. DOI:10.1016/j.soilbio.2010.01.011 |

| [15] |

Soudzilovskaia NA, Douma JC, Akhmetzhanova AA, et al. Global patterns of plant root colonization intensity by mycorrhizal fungi explained by climate and soil chemistry[J]. Global Ecology and Biogeography, 2015, 24(3): 371-382. DOI:10.1111/geb.12272 |

| [16] |

Phillips RP, Brzostek E, Midgley MG. The mycorrhizal-associated nutrient economy: a new framework for predicting carbon-nutrient couplings in temperate forests[J]. New Phytologist, 2013, 199(1): 41-51. DOI:10.1111/nph.12221 |

| [17] |

Teasdale SE, Beulke AK, Guy PL, et al. Environmental barcoding of the ectomycorrhizal fungal genus Cortinarius[J]. Fungal Diversity, 2013, 58(1): 299-310. DOI:10.1007/s13225-012-0218-1 |

| [18] |

Hayward J, Horton TR, Pauchard A, et al. A single ectomycorrhizal fungal species can enable a Pinus invasion[J]. Ecology, 2015, 96(5): 1438-1444. DOI:10.1890/14-1100.1 |

| [19] |

Wang Q, He XH, Guo LD. Ectomycorrhizal fungus communities of Quercus liaotungensis Koidz of different ages in a northern China temperate forest[J]. Mycorrhiza, 2012, 22(6): 461-470. DOI:10.1007/s00572-011-0423-x |

| [20] |

Bonet JA, Fischer CR, Colinas C. The relationship between forest age and aspect on the production of sporocarps of ectomycorrhizal fungi in Pinus sylvestris forests of the central Pyrenees[J]. Forest Ecology and Management, 2004, 203(1/3): 157-175. |

| [21] |

Guo MS, Gao GL, Ding GD, et al. Diversity of ectomycorrhizal fungi associated with Pinus sylvestris var. mongolica in Hulunbuir Sandy Land[J]. Mycosystema, 2018, 37(9): 1133-1142. (in Chinese) 郭米山, 高广磊, 丁国栋, 等. 呼伦贝尔沙地樟子松外生菌根真菌多样性[J]. 菌物学报, 2018, 37(9): 1133-1142. |

| [22] |

Ren Y, Gao GL, Ding GD, et al. Characteristics of organic carbon content of leaf-litter-soil system in Pinus sylvestris var. mongolica plantations[J]. Journal of Beijing Forestry University, 2018, 40(7): 36-44. (in Chinese) 任悦, 高广磊, 丁国栋, 等. 沙地樟子松人工林叶片-枯落物-土壤有机碳含量特征[J]. 北京林业大学学报, 2018, 40(7): 36-44. |

| [23] |

Wang JM, Zhang TH, Li LP, et al. The patterns and drivers of bacterial and fungal β-diversity in a typical dryland ecosystem of Northwest China[J]. Frontiers in Microbiology, 2017, 8: 2126. DOI:10.3389/fmicb.2017.02126 |

| [24] |

Nguyen NH, Song ZW, Bates ST, et al. FUNguild: An open annotation tool for parsing fungal community datasets by ecological guild[J]. Fungal Ecology, 2016, 20: 241-248. DOI:10.1016/j.funeco.2015.06.006 |

| [25] |

Kennedy PG, Hill LT. A molecular and phylogenetic analysis of the structure and specificity of Alnus rubra ectomycorrhizal assemblages[J]. Fungal Ecology, 2010, 3(3): 195-204. DOI:10.1016/j.funeco.2009.08.005 |

| [26] |

Karliński L, Rudawska M, Leski T. The influence of host genotype and soil conditions on ectomycorrhizal community of poplar clones[J]. European Journal of Soil Biology, 2013, 58: 51-58. DOI:10.1016/j.ejsobi.2013.05.007 |

| [27] |

Dejene T, Oria-de-Rueda JA, Martín-Pinto P. Fungal diversity and succession following stand development in Pinus patula Schiede ex Schltdl. & Cham. plantations in Ethiopia[J]. Forest Ecology and Management, 2017, 395: 9-18. DOI:10.1016/j.foreco.2017.03.032 |

| [28] |

Cairney JWG. Basidiomycete mycelia in forest soils: dimensions, dynamics and roles in nutrient distribution[J]. Mycological Research, 2005, 109(1): 7-20. DOI:10.1017/S0953756204001753 |

| [29] |

Long DF, Liu JJ, Han QS, et al. Ectomycorrhizal fungal communities associated with Populus simonii and Pinus tabuliformis in the hilly-gully region of the Loess Plateau, China[J]. Scientific Reports, 2016, 6(1): 24336. DOI:10.1038/srep24336 |

| [30] |

Peay KG, Schubert MG, Nguyen NH, et al. Measuring ectomycorrhizal fungal dispersal: macroecological patterns driven by microscopic propagules[J]. Molecular Ecology, 2012, 21(16): 4122-4136. DOI:10.1111/j.1365-294X.2012.05666.x |

| [31] |

Wei XS, Guo MS, Gao GL, et al. Community structure and functional groups of fungi in the roots associated with Pinus sylvestri var. mongolica in the Hulunbuir Sandy Land[J]. Acta Scientiarum Naturalium Universitatis Pekinensis, 2020, 56(4): 710-720. (in Chinese) 魏晓帅, 郭米山, 高广磊, 等. 呼伦贝尔沙地樟子松根内真菌群落结构与功能群特征[J]. 北京大学学报:自然科学版, 2020, 56(4): 710-720. |

| [32] |

Jakucs E, Erös-Honti Z. Morphological-anatomical characterization and identification of Tomentella ectomycorrhizas[J]. Mycorrhiza, 2008, 18(6/7): 277-285. |

| [33] |

Gehring CA, Mueller RC, Haskins KE, et al. Convergence in mycorrhizal fungal communities due to drought, plant competition, parasitism, and susceptibility to herbivory: consequences for fungi and host plants[J]. Frontiers in Microbiology, 2014, 5: 306. |

| [34] |

Zhang TT, Geng ZC, Xu CY, et al. Diversity of ectomycorrhizal fungi associated with Larixg melinii in Xinjiashan forest region of Qinling Mountains[J]. Acta Microbiologica Sinica, 2018, 58(3): 443-454. (in Chinese) 张彤彤, 耿增超, 许晨阳, 等. 秦岭辛家山林区落叶松外生菌根真菌多样性[J]. 微生物学报, 2018, 58(3): 443-454. |

| [35] |

Yang Y, Yan W, Wei J. Ectomycorrhizal fungal community in the root zone soil of Larix gmelinii var. principis-rupprechtii in Heilihe and Helanshan National Nature Reserve[J]. Mycosystema, 2019, 38(1): 48-63. (in Chinese) 杨岳, 闫伟, 魏杰. 黑里河和贺兰山自然保护区华北落叶松根区土壤中外生菌根真菌群落[J]. 菌物学报, 2019, 38(1): 48-63. |

| [36] |

Lazaruk LW, Macdonald SM, Kernaghan G. The effect of mechanical site preparation on ectomycorrhizae of planted white spruce seedlings in conifer-dominated boreal mixedwood forest[J]. Canadian Journal of Forest Research, 2008, 38(7): 2072-2079. DOI:10.1139/X08-035 |

| [37] |

Zhang WQ, Luo GT, Yu Y, et al. Morphological type and molecular identification of ectomycorrhiza on Pinus sylvestris var. mongolica[J]. Acta Agriculturae Zhejiangensis, 2017, 29(10): 1678-1685. (in Chinese) 张文泉, 罗国涛, 余洋, 等. 樟子松外生菌根形态类型及分子鉴定[J]. 浙江农业学报, 2017, 29(10): 1678-1685. |

| [38] |

Glassman SI, Peay KG, Talbot JM, et al. A continental view of pine-associated ectomycorrhizal fungal spore banks: A quiescent functional guild with a strong biogeographic pattern[J]. New Phytologist, 2015, 205(4): 1619-1631. DOI:10.1111/nph.13240 |

| [39] |

Albornoz FE, Teste FP, Lambers H, et al. Changes in ectomycorrhizal fungal community composition and declining diversity along a 2-million-year soil chronosequence[J]. Molecular Ecology, 2016, 25(19): 4919-4929. DOI:10.1111/mec.13778 |

| [40] |

Tedersoo L, Bahram M, Toots M, et al. Towards global patterns in the diversity and community structure of ectomycorrhizal fungi[J]. Molecular Ecology, 2012, 21(17): 4160-4170. DOI:10.1111/j.1365-294X.2012.05602.x |

| [41] |

Kuzyakov Y, Razav BS. Rhizosphere size and shape: Temporal dynamics and spatial stationarity[J]. Soil Biology and Biochemistry, 2019, 135: 343-360. DOI:10.1016/j.soilbio.2019.05.011 |

| [42] |

Wang K, Song LN, Lü LY, et al. Fine root vertical distribution characters of different aged Pinus sylvestris varr. mongolica plantations on sandy land[J]. Journal of Northeast Forestry University, 2014, 42(3): 1-4. (in Chinese) 王凯, 宋立宁, 吕林有, 等. 不同林龄沙地樟子松人工林细根垂直分布特征[J]. 东北林业大学学报, 2014, 42(3): 1-4. |

| [43] |

Che ZX, Liu XD, Pan X, et al. The variation characteristics of nutrients contents of main dominant tree species in Gansu Province[J]. Ecology and Environmental Sciences, 2015, 24(2): 237-243. (in Chinese) 车宗玺, 刘贤德, 潘欣, 等. 甘肃省典型林区主要优势树种养分含量变化特征分析[J]. 生态环境学报, 2015, 24(2): 237-243. |

| [44] |

Jumpponen A, Brown SP, Trappe JM, et al. Twenty years of research on fungal-plant interactions on Lyman Glacier forefront-lessons learned and questions yet unanswered[J]. Fungal Ecology, 2012, 5(4): 430-442. DOI:10.1016/j.funeco.2012.01.002 |

| [45] |

Gao C, Zhang Y, Shi NN, et al. Community assembly of ectomycorrhizal fungi along a subtropical secondary forest succession[J]. New Phytologist, 2015, 205(2): 771-785. DOI:10.1111/nph.13068 |

| [46] |

Martínez-García LB, Richardson SJ, Tylianakis JM, et al. Host identity is a dominant driver of mycorrhizal fungal community composition during ecosystem development[J]. New Phytologist, 2015, 205(4): 1565-1576. DOI:10.1111/nph.13226 |

| [47] |

Zhao PS, Guo MS, Gao GL, et al. Community structure and functional group of root-associated fungi of Pinus sylvestris var. mongolica across stand ages in the Mu Us Desert[J]. Ecology and Evolution, 2020, 10(6): 3032-3042. DOI:10.1002/ece3.6119 |

| [48] |

Koide RT, Fernandez C, Petprakob K. General principles in the community ecology of ectomycorrhizal fungi[J]. Annals of Forest Science, 2011, 68(1): 45-55. DOI:10.1007/s13595-010-0006-6 |

| [49] |

Guo MS, Gao GL, Ding GD, et al. Drivers of ectomycorrhizal fungal community structure associated with Pinus sylvestris var. mongolica differ at regional vs. local spatial scales in Northern China[J]. Forests, 2020, 11(3): 323. DOI:10.3390/f11030323 |

| [50] |

Sloan WT, Woodcock S, Lunn M, et al. Modeling taxa-abundance distributions in microbial communities using environmental sequence data[J]. Microbial Ecology, 2007, 53(3): 443-455. DOI:10.1007/s00248-006-9141-x |

| [51] |

Nara K. Community developmental patterns and ecological functions of ectomycorrhizal fungi: implications from primary succession[J]. Mycorrhiza, 2008, 581-599. |

| [52] |

Cripps CL, Larsson E, Horak E. Subgenus Mallocybe (Inocybe) in the Rocky Mountain alpine zone with molecular reference to European arctic-alpine material[J]. North American Fungi, 2010, 5(5): 97-126. |

| [53] |

Fan YG, Bau T. Taxonomy in Inocybe subgen. Mallocybe from China[J]. Journal of Fungal Research, 2016, 14(3): 129-132, 141. (in Chinese) 范宇光, 图力古尔. 中国丝盖伞属茸盖亚属分类学研究[J]. 菌物研究, 2016, 14(3): 129-132, 141. |

| [54] |

Kennedy P. Ectomycorrhizal fungi and interspecific competition: species interactions, community structure, coexistence mechanisms, and future research directions[J]. New Phytologist, 2010, 187(4): 895-910. DOI:10.1111/j.1469-8137.2010.03399.x |

| [55] |

Liu Y, Bao G, Song HM, et al. Precipitation reconstruction from Hailar pine (Pinus sylvestris var. mongolica) tree rings in the Hailar region, Inner Mongolia, China back to 1865 AD[J]. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology, 2009, 282(1/4): 81-87. |

| [56] |

Gomez-Reyes MV, Gómez-Peralta M, Guevara GG. New record and distribution of Delastria rosea (Pezizales: Incertae sedis) in Mexico[J]. Acta botánica Mexicana, 2017, 119: 139-144. |

| [57] |

Cullings KW, New MH, Makhija S, et al. Effects of litter addition on ectomycorrhizal associates of a lodgepole Pine (Pinus contorta) stand in Yellowstone National Park[J]. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 2003, 69(7): 3772-3776. DOI:10.1128/AEM.69.7.3772-3776.2003 |

| [58] |

Bödeker ITM, Lindahl BD, Olson Å, et al. Mycorrhizal and saprotrophic fungal guilds compete for the same organic substrates but affect decomposition differently[J]. Functional Ecology, 2016, 30(12): 1967-1978. DOI:10.1111/1365-2435.12677 |

| [59] |

Chu HL, Wang CY, Li ZM, et al. The dark septate endophytes and ectomycorrhizal fungi effect on Pinus tabulaeformis Carr. seedling growth and their potential effects to Pine wilt disease resistance[J]. Forests, 2019, 10(2): 140. DOI:10.3390/f10020140 |

2020, Vol. 47

2020, Vol. 47