扩展功能

文章信息

- 杨恩东, 崔丹曦, 汪维云

- YANG En-Dong, CUI Dan-Xi, WANG Wei-Yun

- 马赛菌属细菌研究进展

- Research progress on the genus Massilia

- 微生物学通报, 2019, 46(6): 1537-1548

- Microbiology China, 2019, 46(6): 1537-1548

- DOI: 10.13344/j.microbiol.china.180573

-

文章历史

- 收稿日期: 2018-07-23

- 接受日期: 2018-11-19

- 网络首发日期: 2018-12-13

马赛菌属(Massilia )菌株隶属于细菌域(Bacteria )变形菌门(Proteobacteria )β变形菌纲(Betaproteobacteria )伯克霍尔德氏菌目(Burkholderiales )草酸杆菌科(Oxalobacteraceae ),目前已发现43个有效描述种,其典型特征为革兰氏染色反应阴性,细胞杆状、不产芽孢、好氧,能运动(M. arvi THG-RS2OT、M. humi THG-S6.8T、M. glaciei B448-2T和M. varians comb. CCUG 35299T除外);其主要脂肪酸有C16:1ω7c 和/或iso -C15:0 2-OH、C18:1ω 7c、C16:0和C10:0 3-OH。主要呼吸醌为Q-8,主要极性脂有双磷脂酰甘油(Diphosphatidylglycerol)、磷脂酰乙醇胺(Phosphatidylethanolamine)和磷脂酰甘油(Phosphatidylglycerol);DNA中(G+C)mol%含量较高,达62.0-69.9 mol%[1-2]。菌落一般为黄色、白色、黄褐色,少数菌株有更加鲜艳的颜色,例如粉红色[3-4]和紫色。

马赛菌属成员表现出多种生理活性,例如,Massilia tieshanensis TS3T能够耐受As3+、Cu2+、Zn2+、Ni2+和Cd2+等多种重金属[5];恶臭马赛菌(M. putida 6NM-7T)能够产生二甲基二硫醚[6];Massilia sp. WG5能够降解菲[7];M. chloroacetimidivorans TA-C7eT能够降解氯乙酰胺[8];Massilia sp. UMI-21能够合成聚羟基烷酸酯(Polyhydroxyalkanoates,PHA)等。因此,马赛菌属菌株在农业、工业、医药和环境等领域具有巨大的潜在应用潜力。本文对马赛菌的发现、建立、生态分布、生物学特性及其应用前景进行综述。

1 马赛菌属的建立及研究现状 1.1 马赛菌属的建立马赛菌属菌株最初是在1998年由La Scola等从一位患有免疫功能缺失的25岁小脑损伤患者的血液中分离的,16S rRNA基因序列分析表明该菌与Duganella zoogloeoides (formerly Zoogloea ramigera 115)和Telluria mixta 相似性最高,进一步研究发现该菌在细胞形态、(G+C)mol%含量和脂肪酸组成等方面与后者存在明显差异,综合基因型与表型特征,以菌株Massilia timonae 为模式菌株,建立了一个新的菌属——马赛菌属(Massilia )[9]。Xu等[10]研究发现在Naxibacter alkalitolerans 中存在一种特殊的极性脂——磷脂酰肌醇甘露糖苷,这是首次在革兰氏阴性菌中发现这种极性脂,因此他们建议将Naxibacter 作为草酸杆菌科的一个新属。但Kämpfer等[11-12]和Weon等[13]研究发现Naxibacter alkalitoleran s 并不含有磷脂酰肌醇甘露糖苷,这与Xu等[10]研究结果明显不同。Kämpfer等[12]认为Massilia 和Naxibacter 属之间并没有明显的属间差异,建议将Naxibater 属下的4个种都重新划分到马赛菌属下。虽然马赛菌属从发现至今只有短短20年时间,但各国学者对此属种的分类以及生物学功效已有较为系统的认识。

1.2 马赛菌属有效发表的种自La Scola等[9]于1998年首次发现Massilia 至今20年间,一些新的马赛菌属新种相继被发现,截至2018年9月,已经正式发表的马赛菌属细菌种有43个,其中从土壤中分离发现的菌种数量最多,包括M. agri K3-1T[14],M. alkalitolerans YIM 31775T (Naxibacter alkalitolerans YIM 31775T),M. arvi THG-RS2OT[15],M. brevitalea byr23-80T[16],M. chloroacetimidivorans TA-C7eT[8],M. flava Y9T[17],M. albidiflava 45T,M. dura 16T,M. lutea 101T,M. plicata 76T[18],M. humi THG-S6.8T[19],M .kyonggiensis TSA1T[20],M. lurida D5T[21],M. namucuonensis 333-1-0411T[22],M. neuiana PTW21T[23],M. phosphatilytica 12OD1T[24],M. pinisoli T33T[25],M. putida 6NM-7T[6],M. agilis J9T,M. solisilvae J18T,M. terrae J11T[26],M. tieshanensis TS3T[5],M. umbonata LPO1T[27],M. violacea CAVIOT[28]和M. armeniaca T[29]等;其次是从空气中分离的,包括M. aerilata 5516S-11T[30],M. jejuensis 5317J-18T,M. suwonensis (Naxibacter suwonensis 5414S-25T)[13],M. niabensis 5420S-26T,M. niastensis 5516S-1T[31]和M. norwichensis NS9T[3]等;从水中分离的菌株有M. aurea AP13T[32];从冰川中分离的菌株包括M. eurypsychrophila B528-3T[4],M. glaciei B448-2T[2],M. psychrophila B1555-1T[33],M. yuzhufengensis Y1243-1T[34]和M. violaceinigra B2T[35]等;从人类临床标本分离的菌株有M. oculi CCUG 43427AT[36],M. timonae UR/MT95T[9],M. varians CCUG 35299T (Naxibacter varians CCUG 35299T),M. haematophilus (Naxibacter haematophilus CCUG 38318T)和Massilia consociata CCUG 58010T[11-12];此外还有分离自岩石表面的马赛菌,如M. buxea A9T[1]。显然,土壤是马赛菌的主要生存环境,占总菌种数的60%,另外空气、水、岩石表面及生物体内等生境也有马赛菌的分布。已发表的马赛菌菌种名称及其分离生境信息等详见表 1。

| 种名 Species |

栖息地 Habitat |

具体类型 Specific type |

温度 Growth temperature (℃) |

酸碱度 pH |

功能 Function |

参考文献 References |

| M. aurea AP13T | 水 Water |

饮用水 Drinking water |

4-30 | 4.0-9.0 | 黄色素 Yellow pigment |

[32] |

| M. eurypsychrophila B528-3T | 冰芯 Ice core |

慕士塔格冰川 Muztagh Glacier |

0-25 | 5.0-10.0 | 粉色素 Pink pigment |

[4] |

| M. glaciei B448-2T | 冰芯 Ice core |

慕士塔格冰川 Muztagh Glacier |

4-30 | 5.0-9.0 | - | [2] |

| M. psychrophila B1555T | 冰芯 Ice core |

慕士塔格冰川 Muztagh Glacier |

10-25 | 6.0-9.0 | 黄色素 Yellow pigment |

[33] |

| M. yuzhufengensis Y1243-1T | 冰芯 Ice core |

玉珠峰冰川 Yuzhufeng Glacier |

2-35 | 5.0-8.0 | 黄色素 Yellow pigment |

[34] |

| M. violaceinigra B2T | 土壤 Soil |

永久冻土 Permafrost |

4-28 | 5.0-9.0 | 紫色素 Purple pigment |

[35] |

| M. agilis J9T,M. solisilvae J18T,M. terrae J11T | 土壤 Soil |

森林土壤 Forest soil |

4-46 | 4.0-9.0 | - | [26] |

| M. agri K3-1T | 土壤 Soil |

开垦草地土壤 Reclaimed grassland soil |

4-45 | 5.0-10.0 | 黄色素 Yellow pigment |

[14] |

| M. albidiflava 45T,M. dura 16T,M. plicata 76T,M. lutea 101T | 土壤 Soil |

重金属污染土壤 soil samples polluted with heavy metals |

10-45 | 6·5-8·5 | 黄色素 Yellow pigment |

[18] |

| M. alkalitolerans comb YIM 31775T | 土壤 Soil |

土壤 Soil |

4-55 | 6.0-12.0 | 耐碱 Alkali resisting |

[10] |

| M. arvi THG-RS2OT | 土壤 Soil |

休耕土壤 Fallow-land soil |

10-42 | 6.5-7.0 | 产铁载体 Siderophore producing |

[15] |

| M. brevitalea byr23-80T | 土壤 Soil |

土壤浓度计 Lysimeter soil |

4-30 | 7.0-7.5 | 细胞表面有大量瘤状突起,二元分裂 Numerous protuberances of the cell envelope, divided by binary fission |

[16] |

| M.chloroacetimidivorans TA-C7eT | 土壤 Soil |

农田土壤 Agricultural soil |

15-40 | 6.0-7.5 | 降解氯乙酰胺(除草剂) Chloroacetamide-degrading (herbicide) |

[8] |

| M. flava Y9T | 土壤 Soil |

土壤 Soil |

10-45 | 6.5-8.5 | 黄色素 Yellow pigment |

[17] |

| M. humi THG-S6.8T | 土壤 Soil |

土壤 Soil |

4-42 | 6.0-9.5 | - | [19] |

| M. kyonggiensis TSA1T | 土壤 Soil |

森林土壤 Forest soil |

25-37 | 5.0-9.0 | - | [20] |

| M. lurida D5T | 土壤 Soil |

向日葵试验田土壤 Experimental sunflower field |

10-37 | 6.0-9.0 | 黄色素 Yellow pigment |

[21] |

| M. namucuonensis 333-1-0411T | 土壤 Soil |

盐湖岸边土 Saltwater Lake |

4-37 | 5.5-9.5 | - | [22] |

| M. neuiana PTW21T | 土壤 Soil |

河边湿润土壤 Riverbank wet soil |

10-45 | 4.5-12.5 | - | [23] |

| M. phosphatilytica 12OD1T | 土壤 Soil |

长期施肥农田土壤 Long-term fertilized soil |

4-34 | 5.0-8.0 | 溶磷 Phosphate-solubilizing |

[24] |

| M. pinisoli T33T | 土壤 Soil |

森林土壤 Forest soil |

10-37 | 5.0-9.0 | - | [25] |

| M. putida 6NM-7 T | 土壤 Soil |

钨矿山尾矿 Wolfram mine tailing |

25-37 | 6.0-8.0 | 抗重金属,产二甲基二硫醚 Resistant to heavy metals, dimethyl disulfide-producing |

[6] |

| M. tieshanensis TS3T | 土壤 Soil |

矿区土壤(砷污染) Mining soil (arsenic pollution) |

10-40 | 5.0-9.0 | 抗重金属 Resistant to heavy metals |

[5] |

| M. umbonata LPO1T | 土壤 Soil |

土壤与污水堆肥样品 Sewage sludge compost-soil |

4-37 | 7.0-8.0 | 产生多聚β羟基丁酸酯 Accumulate poly-β-hydroxybutyrate |

[27] |

| M. violacea CAVIOT | 土壤 Soil |

河岸土 Riverbank soil |

10-35 | 5.8-9.2 | 紫色素 Purple pigment |

[28] |

| M. armeniaca ZMN-3T | 土壤 Soil |

沙漠土壤 Desert soil |

10-45 | 5.0-9.0 | 黄色素 Yellow pigment |

[29] |

| M. buxea A9T | 岩石 Rock |

湖边岩石表面 | 10-37 | 6.0-9.0 | 黄色素 Yellow pigment |

[1] |

| M. aerilata 5516S-11T | 空气 Air |

空气 Air |

5-35 | 5.0-9.0 | - | [30] |

| M.niabensis 5420S-2T, M. niastensis 5516S-1T | 空气 Air |

空气 Air |

5-35 | 7.0-9.0 | - | [31] |

| M. norwichensis NS9T | 空气 Air |

空气 Air |

- | - | - | [3] |

| M . haematophilus comb. CCUG38318T | 人体 Humen |

患者血液 Human blood |

15-37 | 5.5-10.5 | - | [11] |

| Massilia consociata CCUG 58010T | 人体 Humen |

血液 Blood |

25-30 | 5.5-10.5 | - | [12] |

| M. oculi CCUG 43427AT | 人体 Humen |

眼内炎患者眼部 Eye of a patient suffering from endophthalmitis |

15-37 ℃ | 5.5-10.5 | - | [36] |

| M. timonae UR/MT95T | 人体 Humen |

患者血液 Human blood |

28-37 | - | - | [9] |

| M. varians comb. CCUG 35299T | 人体 Humen |

90岁老人眼部 Eye of a 90-year-old man |

15-37 | 5.5-10.5 | - | [11] |

| 注:-:未见报道. Note: -: No reference. |

||||||

|

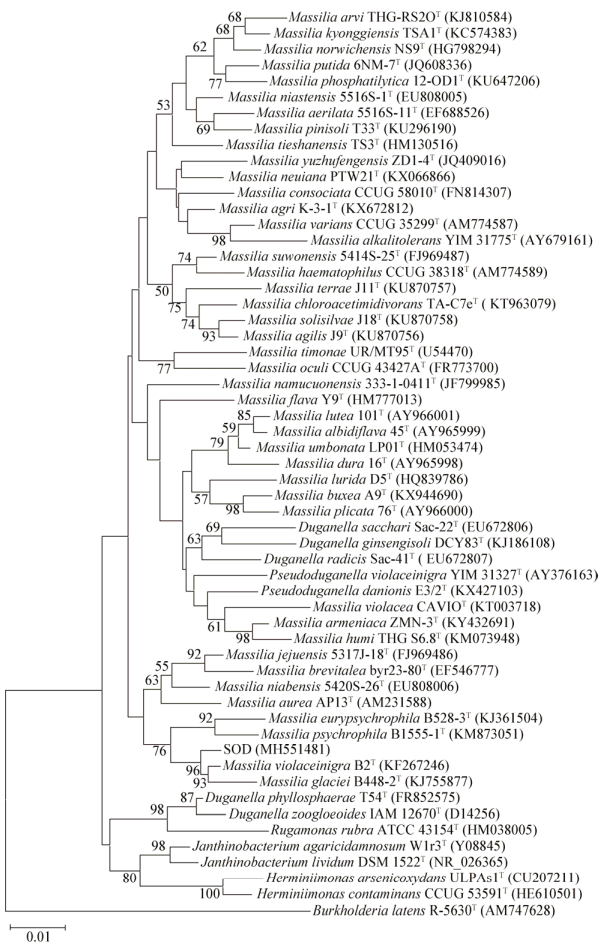

| 图 1 基于马赛菌属代表菌株及相关菌株的16S rRNA基因序列构建的系统进化树 Figure 1 Neighbor-Joining phylogenetic tree based on 16S rRNA gene sequences of the representative members of the genera of Massilia and some other related taxa 注:菌株名称后括号内的序号为NCBI序列编号;分支点上数字为重复1 000次的自展值;标尺0.01为核苷酸替换率. Note: NCBI accession numbers were listed behind strain numbers in parentheses; Numbers at nodes indicate percentage levels of bootstrap support based on a Neighbor-Joining analysis of 1 000 resampled datasets; The scale bar indicates 0.01 substitutions per nucleotide position. |

|

|

本实验室分别从岩石表面和土壤分离得到了2株马赛菌A9和SOD。基于16S rRNA基因序列、DNA-DNA杂交以及呼吸醌等多相分类学实验结果,将菌株A9鉴定为马赛菌属的一个新种,命名为M. buxea A9T[1] (菌株SOD部分研究工作将另文发表)。

2 马赛菌属细菌种分布的生境多样性马赛菌属细菌在全球分布广泛,先后在中国[1, 4, 24, 33-34]、韩国[26, 31]、尼泊尔[14]、西班牙[32, 37]和英国[3]等不同国家的不同自然环境中被发现。

马赛属细菌除了分布广泛,其分布地点的生态环境也十分多样,目前已发现不仅在冰、水、土壤等生境广泛存在,而且能在岩石表层、空气和植物体内稳定生存,还有部分菌株分离自人类临床样本,比如病患的血液或眼睛。

2.1 冰水环境2006年,Gallego等[32]在西班牙塞维利亚地区的应用水系统中分离到了菌株M. aurea AP13T,该菌株可在pH 4.0-9.0的水中存活,这是第一株分离自水中的马赛属菌株。此外,研究者从冰川冰芯中也分离到了许多马赛菌。自从Anesio和Laybourn Parry在2012年提出“目前地球上最寒冷的生物群系并不是分布在苔原,而是分布在南北极以及青藏高原冰冻圈”后,这些极寒生境中耐低温的极端微生物成为人们研究的热点[38]。近年来刘勇勤等先后从青藏高原玉珠峰冰芯和新疆慕士塔格冰川的冰芯中分离出菌株M. yuzhufengensis Y1243T[34]、M. eurypsychrophila [4]、M. psychrophila B1555T[33]和M. glaciei B448-2T[2],这些分离自寒冷环境下的菌株可在0-25℃生长,而且马赛菌表现出的耐低温性在工业上有潜在的应用价值。马赛菌属对温度也表现出高度的适应性,不同的马赛菌能够在0-55℃范围内生长(表 1)。

2.2 土壤研究者一般倾向于研究特殊地域土壤的微生物,例如重金属污染土壤,或是施肥过量的农田土壤。M. tieshanensis TS3T是从湖北大冶市铁山区土壤中分离出的菌株,由于该地常年熔炼金、铜等重金属,砷和其他重金属的浓度在这一地区水、土壤和沉积物中含量极高,土壤砷浓度高达337.2 mg/kg。菌株M. tieshanensis TS3T能够耐受As3+、Cu2+、Zn2+、Ni2+和Cd2+等多种重金属,而且其对Cu2+的耐受性高达4 mmol/L,明显高于其同属的其他菌株[5]。此外,从其它特殊土壤环境也分离到了若干马赛菌,例如菌株M. phosphatilytica 12OD1T分离自黑龙江地区某长期施肥的土壤中[24];菌株M. agri K-3-1T分离自尼泊尔开垦草地土壤[14];M. dura 16T、M. albidiflava 45T、M. plicata 75T和M. lutea 101T分离自中国南京郊区受重金属污染的农田土壤[18];M. pinisoli T33T分离自韩国京畿大学森林土壤[25];M. umbonata LPO1T[27]分离自污泥混合物等。

2.3 空气Weon等[30]在研究空气中的细菌数量时,分离到一株菌落为黄色的菌株5516S-11T,经鉴定为马赛菌属的一个新种,被命名为M. aerilata 5516S-11T。随后Weon等[13, 31]又陆续从空气中分离发现了4株马赛属新菌,分别是M. jejuensis 、M. niabensis 、M. niastensis 和M. suwonensis 。

2.4 生物体内Kämpfer等[36]从一个眼内炎患者的眼睛内分离出马赛菌M. oculi ,此菌对pH表现出高度适应性,能在pH 5.5-10.5的环境中存活。Park等[39]在病患耳鼓膜内脓液分离到一株能导致中耳炎的致病原细菌,这是Massilia sp.首次作为致病原细菌被发现。Bassas-Galia等[37]从植物体分离到6株马赛菌,16S rRNA基因序列分析发现,菌株4D6、5F6、2C4和4D3c与M. plicata 、M. niabensis 、M. niastensis 和M. aerilata 相似性分别为99.9%、99.3%、97.5%和97.9%。Massilia sp. UMI-21分离自一种称为石莼的海藻[40]。

3 马赛菌的应用研究由于马赛菌属菌株分布广、适应环境能力强且具有潜在的重要应用价值,其应用研究一直受到人们的重视,并主要集中在土壤修复、产酶和其他代谢产物等方面。

3.1 土壤修复与改良 3.1.1 产生二甲基二硫醚 溴甲烷是一种效果显著的土壤熏蒸剂,但因其会破坏臭氧层,严重危害到地球环境和人类健康,国际上正在大力寻找替代溴甲烷的新型土壤熏蒸剂。二甲基二硫醚(DMDS)是联合国溴甲烷技术选择委员会提出的一种新型的土壤熏蒸剂替代品,在防治土壤病原真菌以及杀灭线虫方面具有显著效果。2016年,Feng等[6]在中国江西大余县钨矿区的矿砂中分离获得了恶臭马赛菌(M. putida) 6NM-7,它能够产生二甲基二硫醚,表明该菌株在防治土传病害和研发新型土壤熏蒸剂等方面具有潜在应用价值。 3.1.2 降解多环芳烃菲和氯乙酰胺类除草剂 菲是一种三环的多环芳烃,而多环芳烃(Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons,PAHs)是一种挥发性的有机污染物,具有潜在的致癌以及致畸性。PAHs具有低水溶性和疏水性,能强烈地分配到非水相中,吸附于土壤颗粒物中,并通过生物富集进入食物链,危害人体健康。近年来,多环芳烃污染土壤的修复与治理已引起各国学者的广泛关注[41-43],研究表明微生物降解是消除环境中多环芳烃的最有效途径[44-45]。2016年Wang等[46]从多环芳烃污染土壤中分离到一株高效降解菲的菌株WF1,经形态学观察、生理生化特征和16S rRNA基因序列分析,鉴定WF1属于马赛菌属。Lou等[7]也从江苏地区多环芳烃高度污染的土壤中分离出了能降解菲的菌株WG5,经鉴定为马赛菌。可见马赛菌属的部分菌株在修复菲污染土壤方面具有潜在应用价值。酰胺类除草剂是目前世界上用量最大的除草剂之一,其中氯乙酰胺又在其中占很大比例,其在抑制作物杂草危害的同时也污染了环境。Lee等[8]从农田土壤中分离筛选到一株能够降解氯乙酰胺的菌株TA-C7e,鉴定为M. chloroacetimidivorans TA-C7eT。

3.1.3 重金属抗性 重金属抗性菌株的分离筛选是利用微生物修复重金属污染水土的首要前提。Du等[5]从湖北省大冶市铁山区的金属矿土中筛选出一株细菌TS3,多相分类鉴定表明菌株TS3属于马赛菌属,并命名为M. tieshanensis TS3T,该菌株对As3+、Cu2、Sb3+、Zn2+、Ni2+和Cd2+均有抗性;Feng等[6]发现M. putida 6NM-7T能够耐受1.0 mmol/L Cd2+、0.5 mmol/L Zn2+和1.5 mmol/L Pb2+。由此可见,马赛菌属的部分菌株具有抗多种重金属的能力,但关于马赛菌修复土壤或水体重金属污染的研究还未见报道。 3.1.4 溶磷功能 磷是植物生长所必需的元素之一,但只有5%-25%的磷肥被作物吸收利用,其它都被土壤里的Ca2+、Fe3+、Al3+所固定成为植物不可利用的磷形态。因此,如何提高土壤中有效磷含量已成为当前农业微生物的研究热点。研究表明溶磷微生物不仅能够提高土壤中有效磷含量,并且还能够改善土壤环境。M. phosphatilytica 12-OD1T分离自中国黑龙江省海伦市一片长期施肥的土壤,研究发现该菌具有溶磷作用,这是第一次发现马赛菌属细菌具有溶磷能力[24]。M. phosphatilytica 12-OD1T等马赛菌改善土壤磷素及植物磷营养状况的研究有待进一步加强。 3.2 产酶研究酶法降解甲壳素无污染、条件温和且产物单一,但由于甲壳素酶活力过低导致生产周期长,使得酶法降解成本颇高。Faramarzi等[47]在2009年发现菌株M. timonae U2能够产生甲壳素酶,这是马赛菌属中首次被发现能够产生甲壳素酶的菌株,进一步研究发现该菌株甲壳素酶的产量随培养基中碳源的改变而变化。2010年韩宝芹等[48]从海边土壤中分离筛选出一株甲壳素酶活力较高的马赛菌菌株HD002,其产甲壳素酶活力高于M. timonae U2,进而通过优化发酵条件,HD002菌株的发酵液酶活力可达到1.314 U/mL,为M. timonae 菌株发酵液酶活力的8.21倍。因此,新菌株HD002的获得对酶法降解甲壳素具有重要的研究意义。

低温酶在应用于工业生产时不需要额外耗能去提升反应体系温度,因而节约了成本,因此在纺织业、造纸业、食品加工业以及洗涤剂生产行业具有巨大潜力而受到格外关注。刘璐等[49]对分离自极地的136株细菌进行筛选获得一株能够产生甘露聚糖酶、淀粉酶、纤维素酶等多糖水解酶的菌株,16S rRNA基因序列分析表明该菌与M. eurypsychrophila 具有98.32%的相似性,属于马赛菌属,该菌株能在20 ℃的环境下迅速生长,对其进行全基因组测序,序列分析表明M. eurypsychrophila 709含有2个α-淀粉酶基因、1个木聚糖酶基因和1个壳聚糖酶基因。

3.3 次生代谢产物 3.3.1 紫色杆菌素 紫色杆菌素是微生物产生的由2个色氨酸分子氧化缩合而成的一种代谢产物,属于吲哚衍生物,为非水溶性的蓝黑色色素。近年来,研究者发现紫色杆菌素具有广谱抗菌、抗肿瘤、抗疟疾、抗氧化和止泻等功效,在医药领域中具有良好的应用前景[50-55]。Agematu等[56]从土壤中分离到一株能够产生紫色杆菌素(Violacein)和脱氧紫色杆菌素(Deoxyviolacein)的马赛菌,这是首次发现马赛菌能够产生紫色杆菌素和脱氧紫色杆菌素的报道。Yoon等[57]从森林土壤中分离到一株Massilia sp. EP 155224也能够产生紫色杆菌素,在最优条件下紫色杆菌素产量高达280 mg/L。Massilia sp. NR 4-1是一株分离自韩国肉豆蔻树下表层土壤的新菌种,Myeong等[58]对其进行了全基因组序列的测定,发现其基因组内存在紫色杆菌素的代谢途径——vio ABCDE,该菌株基因组图的完成对进一步研究紫色杆菌素代谢途径奠定了基础。

3.3.2 聚羟基烷酸酯 聚羟基烷酸酯(Polyhydroxyalkanoates,PHA)是一类由生物合成的高分子聚合物,具有生物相容性和无毒性,可用来代替现有塑料材料,在医学领域具有重要的应用价值,比如制作手术缝合线、创口覆盖膜等医疗器械,以及用作克隆器官的支架材料等[59]。大规模开发PHA的关键障碍是其高昂的生产成本,因此降低PHA的生产成本是关键。2012年,Bassas-Galia等[37]从植物中分离到6株能够以甘油或葡萄糖为前体高效合成PHA的菌株,16S rRNA基因序列分析显示这6株菌均为马赛菌,其中Massilia sp. 4D6可利用生物柴油的副产物甘油合成PHA,产量高达46% (质量比),可以充分发挥副产物甘油的经济效益。Han等[40]从一种含有淀粉的海藻-石莼中分离到一株菌Massilia sp. UMI-21,该菌能够利用淀粉、麦芽三糖或麦芽糖作为唯一碳源合成多羟基烃酸酯(PHA),利用10L发酵罐发酵该菌株,PHA产量高达45.5% (质量比),高于前人在三角瓶发酵中的产量。因很多海藻中都存在大量淀粉,是一种相对廉价的基质,因此该研究中所分离的菌株在未来PHA生产中具有极大的潜在价值。

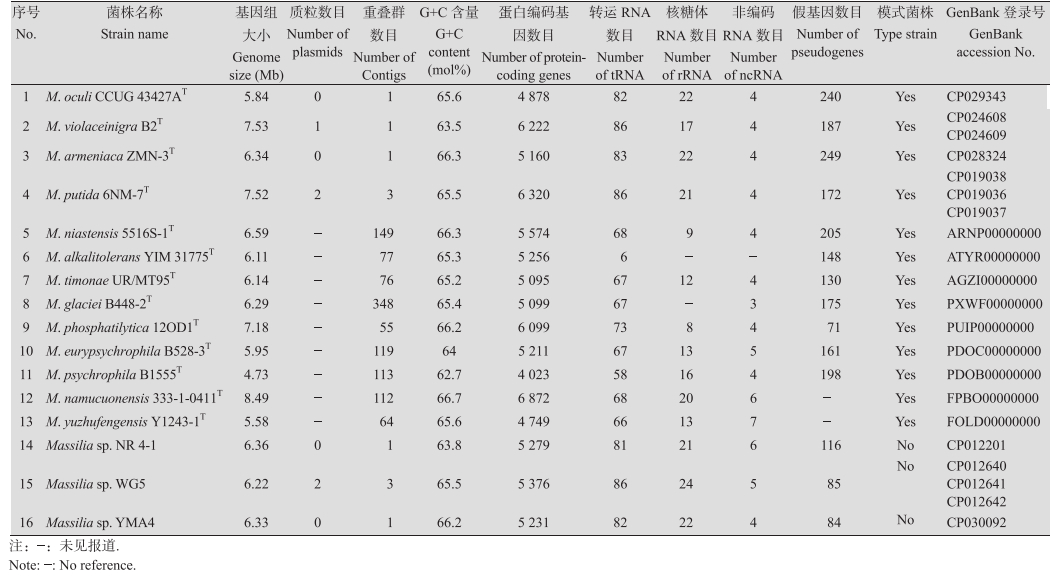

4 马赛菌属前景展望近年来,三代测序技术(单分子实时测序仪)发展迅速,在一定程度上促进了马赛菌基因组学的研究[60]。截至2018年9月,已提交至NCBI完成全基因组测序的马赛菌属菌株有7株(其中3株为有效描述种的典型菌株),基因组草图 39株(其中9株为有效描述种的典型菌株)。已完成的马赛菌基因组全图概况见表 2。从表 2可以看出,已经完成全基因组测序的7株马赛菌中:基因组大小在5.8-7.5 Mb之间,(G+C)mol%含量较高,大多数在63 mol%-66 mol%之间,编码蛋白的基因数目为4 880-6 320,编码蛋白的基因数目最多的为M. putida 6NM-7 T,最少的为M. oculi CCUG 43427AT。菌株M. putida 6NM-7T和Massilia sp. WG5各含有2个质粒,M. violaceinigra B2T含有1个质粒。马赛菌基因组学研究逐渐引起人们的关注,但关于其分子生物学和遗传学方面的研究鲜见报道,进行全基因组测序并在整个基因组范围内比对,在功能基因组学水平进行深入研究,有助于发掘未知功能的独特基因,为进一步研究马赛菌的功能、应用及其作用机制提供新契机。

|

自1998年La Scola等[9]建立Massilia 以来,在之后的8年多时间,一直没有新的成员被报道。随着近年来马赛菌属新成员不断被发现,关于其生理生化方面的研究逐渐展开,研究者从马赛菌中发现了新型高效的环糊精酶、β酰胺酶和耐盐的木聚糖酶等[61-63];此外,研究发现马赛菌还能降解百菌清、菲、苯和烟碱等[64-66],但是关于其降解机制还并不清楚。马赛菌属菌株在工农业生产、食品行业和污染环境修复等领域具有广阔的应用前景,但与其它属种和菌株相比,该类群发现的种和菌株仍非常有限,新菌株资源挖掘潜力巨大。不断挖掘发现新的马赛菌属种和新菌株、进一步开发其功能并研究其遗传代谢与分子调控机制是未来研究的重点。

| [1] |

Sun LN, Yang ED, Cui DX, et al. Massilia buxea sp. nov., isolated from a rock surface[J]. International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology, 2017, 67(11): 4390-4396. DOI:10.1099/ijsem.0.002301 |

| [2] |

Gu ZQ, Liu YQ, Xu BQ, et al. Massilia glaciei sp. nov., isolated from the muztagh glacier[J]. International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology, 2017, 67(10): 4075-4079. DOI:10.1099/ijsem.0.002252 |

| [3] |

Orthova I, Kämpfer P, Glaeser SP, et al. Massilia norwichensis sp. nov., isolated from an air sample[J]. International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology, 2015, 65(1): 56-64. |

| [4] |

Shen L, Liu YQ, Gu ZQ, et al. Massilia eurypsychrophila sp. nov. a facultatively psychrophilic bacteria isolated from ice core[J]. International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology, 2015, 65(7): 2124-2129. DOI:10.1099/ijs.0.000229 |

| [5] |

Du Y, Yu X, Wang GJ. Massilia tieshanensis sp. nov., isolated from mining soil[J]. International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology, 2012, 62(10): 2356-2362. |

| [6] |

Feng GD, Yang SZ, Li HP, et al. Massilia putida sp. nov., a dimethyl disulfide-producing bacterium isolated from wolfram mine tailing[J]. International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology, 2016, 66(1): 50-55. DOI:10.1099/ijsem.0.000670 |

| [7] |

Lou J, Gu HP, Wang HZ, et al. Complete genome sequence of Massilia sp. WG5, an efficient phenanthrene-degrading bacterium from soil[J]. Journal of Biotechnology, 2016, 218: 49-50. DOI:10.1016/j.jbiotec.2015.11.026 |

| [8] |

Lee H, Kim DU, Park S, et al. Massilia chloroacetimidivorans sp. nov., a chloroacetamide herbicide-degrading bacterium isolated from soil[J]. Antonie van Leeuwenhoek, 2017, 110(6): 751-758. DOI:10.1007/s10482-017-0845-3 |

| [9] |

La Scola B, Birtles RJ, Mallet MN, et al. Massilia timonae gen. nov., sp. nov., isolated from blood of an immunocompromised patient with cerebellar lesions[J]. Journal of Clinical Microbiology, 1998, 36(10): 2847-2852. |

| [10] |

Xu P, Li WJ, Tang SK, et al. Naxibacter alkalitolerans gen. nov., sp. nov., a novel member of the family 'Oxalobacteraceae ' isolated from China[J]. International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology, 2005, 55(3): 1149-1153. DOI:10.1099/ijs.0.63407-0 |

| [11] |

Kämpfer P, Falsen E, Busse HJ. Naxibacter varians sp. nov. and Naxibacter haematophilus sp. nov., and emended description of the genus Naxibacter [J]. International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology, 2008, 58(7): 1680-1684. DOI:10.1099/ijs.0.65516-0 |

| [12] |

Kämpfer P, Lodders N, Martin K, et al. Revision of the genus Massilia La Scola et al . 2000, with an emended description of the genus and inclusion of all species of the genus Naxibacter as new combinations, and proposal of Massilia consociata sp. nov.[J]. International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology, 2011, 61(7): 1528-1533. DOI:10.1099/ijs.0.025585-0 |

| [13] |

Weon HY, Yoo SH, Kim SJ, et al. Massilia jejuensis sp. nov. and Naxibacter suwonensis sp. nov., isolated from air samples[J]. International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology, 2010, 60(8): 1938-1943. DOI:10.1099/ijs.0.015479-0 |

| [14] |

Chaudhary DK, Kim J. Massilia agri sp. nov., isolated from reclaimed grassland soil[J]. International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology, 2017, 67(8): 2696-2703. DOI:10.1099/ijsem.0.002002 |

| [15] |

Singh H, Du J, Won K, et al. Massilia arvi sp. nov., isolated from fallow-land soil previously cultivated with Brassica oleracea , and emended description of the genus Massilia [J]. International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology, 2015, 65(10): 3690-3696. DOI:10.1099/ijsem.0.000477 |

| [16] |

Zu D, Wanner G, Overmann J. Massilia brevitalea sp. nov., a novel betaproteobacterium isolated from lysimeter soil[J]. International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology, 2008, 58(5): 1245-1251. DOI:10.1099/ijs.0.65473-0 |

| [17] |

Wang JW, Zhang JL, Pang HC, et al. Massilia flava sp. nov., isolated from soil[J]. International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology, 2012, 62(3): 580-585. |

| [18] |

Zhang YQ, Li WJ, Zhang KY, et al. Massilia dura sp. nov., Massilia albidiflava sp. nov., Massilia plicata sp. nov. and Massilia lutea sp. nov., isolated from soils in China[J]. International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology, 2006, 56(2): 459-463. DOI:10.1099/ijs.0.64083-0 |

| [19] |

Du J, Yin CS. Massilia humi sp. Nov. isolated from soil in Incheon, South Korea[J]. Archives of Microbiology, 2016, 198(4): 363-367. DOI:10.1007/s00203-016-1195-7 |

| [20] |

Kim J. Massilia kyonggiensis sp. nov., isolated from forest soil in Korea[J]. Journal of Microbiology, 2014, 52(5): 378-383. DOI:10.1007/s12275-014-4010-7 |

| [21] |

Luo XN, Xie Q, Wang JW, et al. Massilia lurida sp. nov., isolated from soil[J]. International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology, 2013, 63(6): 2118-2123. |

| [22] |

Kong BH, Li YH, Liu M, et al. Massilia namucuonensis sp. nov., isolated from a soil sample[J]. International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology, 2013, 63(1): 353-357. |

| [23] |

Zhao X, Li XJ, Qi N, et al. Massilia neuiana sp. nov., isolated from wet soil[J]. International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology, 2017, 67(12): 4943-4947. DOI:10.1099/ijsem.0.002333 |

| [24] |

Zheng BX, Bi QF, Hao XL, et al. Massilia phosphatilytica sp. nov., a phosphate solubilizing bacteria isolated from a long-term fertilized soil[J]. International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology, 2017, 67(8): 2514-2519. DOI:10.1099/ijsem.0.001916 |

| [25] |

Altankhuu K, Kim J. Massilia pinisoli sp. nov., isolated from forest soil[J]. International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology, 2016, 66(9): 3669-3674. DOI:10.1099/ijsem.0.001249 |

| [26] |

Altankhuu K, Kim J. Massilia solisilvae sp. nov., Massilia terrae sp. nov. and Massilia agilis sp. nov., isolated from forest soil in South Korea by using a newly developed culture method[J]. International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology, 2017, 67(8): 3026-3032. DOI:10.1099/ijsem.0.002076 |

| [27] |

Rodríguez-Díaz M, Cerrone F, Sánchez-Peinado M, et al. Massilia umbonata sp. nov., able to accumulate poly-β-hydroxybutyrate, isolated from a sewage sludge compost-soil microcosm[J]. International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology, 2014, 64(1): 131-137. |

| [28] |

Embarcadero-Jiménez S, Peix #193;, Igual JM, et al. Massilia violacea sp. nov., isolated from riverbank soil[J]. International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology, 2016, 66(2): 707-711. DOI:10.1099/ijsem.0.000776 |

| [29] |

Ren MN, Li XY, Zhang YQ, et al. Massilia armeniaca sp. nov., isolated from desert soil[J]. International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology, 2018, 68(7): 2319-2324. DOI:10.1099/ijsem.0.002836 |

| [30] |

Weon HY, Kim BY, Son JA, et al. Massilia aerilata sp. nov., isolated from an air sample[J]. International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology, 2008, 58(6): 1422-1425. DOI:10.1099/ijs.0.65419-0 |

| [31] |

Weon HY, Kim BY, Hong SB, et al. Massilia niabensis sp. nov. and Massilia niastensis sp. nov., isolated from air samples[J]. International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology, 2009, 59(7): 1656-1660. DOI:10.1099/ijs.0.006908-0 |

| [32] |

Gallego V, Sánchez-Porro C, García MT, et al. Massilia aurea sp. nov., isolated from drinking water[J]. International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology, 2006, 56(7): 2449-2453. |

| [33] |

Guo BX, Liu YQ, Gu ZQ, et al. Massilia psychrophila sp. nov., isolated from an ice core[J]. International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology, 2016, 66(10): 4088-4093. DOI:10.1099/ijsem.0.001315 |

| [34] |

Shen L, Liu YQ, Wang NL, et al. Massilia yuzhufengensis sp. nov., isolated from an ice core[J]. International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology, 2013, 63(4): 1285-1290. |

| [35] |

Wang HS, Zhang XX, Wang SY, et al. Massilia violaceinigra sp. nov., a novel purple-pigmented bacterium isolated from glacier permafrost[J]. International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology, 2018, 68(7): 2271-2278. DOI:10.1099/ijsem.0.002826 |

| [36] |

Kämpfer P, Lodders N, Martin K, et al. Massilia oculi sp. nov., isolated from a human clinical specimen[J]. International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology, 2012, 62(2): 364-369. DOI:10.1099/ijs.0.032441-0 |

| [37] |

Bassas-Galia M, Nogales B, Arias S, et al. Plant original Massilia isolates producing polyhydroxybutyrate, including one exhibiting high yields from glycerol[J]. Journal of Applied Microbiology, 2012, 112(3): 443-454. DOI:10.1111/jam.2012.112.issue-3 |

| [38] |

Anesio AM, Laybourn-Parry J. Glaciers and ice sheets as a biome[J]. Trends in Ecology & Evolution, 2012, 27(4): 219-225. |

| [39] |

Park MK, Shin HB. Massilia sp. isolated from otitis media[J]. International Journal of Pediatric Otorhinolaryngology, 2013, 77(2): 303-305. DOI:10.1016/j.ijporl.2012.11.011 |

| [40] |

Han XR, Satoh Y, Kuriki Y, et al. Polyhydroxyalkanoate production by a novel bacterium Massilia sp. UMI-21 isolated from seaweed, and molecular cloning of its polyhydroxyalkanoate synthase gene[J]. Journal of Bioscience and Bioengineering, 2014, 118(5): 514-519. DOI:10.1016/j.jbiosc.2014.04.022 |

| [41] |

Gutierrez T, Rhodes G, Mishamandani S, et al. Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon degradation of phytoplankton-associated Arenibacter spp. and description of Arenibacter algicola sp. nov., an aromatic hydrocarbon-degrading bacterium[J]. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 2014, 80(2): 618-628. DOI:10.1128/AEM.03104-13 |

| [42] |

Olivera NL, Commendatore MG, Delgado O, et al. Microbial characterization and hydrocarbon biodegradation potential of natural bilge waste microflora[J]. Journal of Industrial Microbiology and Biotechnology, 2003, 30(9): 542-548. DOI:10.1007/s10295-003-0078-5 |

| [43] |

Dutta K, Shityakov S, Das PP, et al. Enhanced biodegradation of mixed PAHs by mutated naphthalene 1, 2-dioxygenase encoded by Pseudomonas putida strain KD6 isolated from petroleum refinery waste[J]. 3 Biotech, 2017, 7(6): 365. DOI:10.1007/s13205-017-0940-1 |

| [44] |

Alegbeleye OO, Opeolu BO, Jackson V. Bioremediation of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon (PAH) compounds: (acenaphthene and fluorene) in water using indigenous bacterial species isolated from the Diep and Plankenburg rivers, Western cape, South africa[J]. Brazilian Journal of Microbiology, 2017, 48(2): 314-325. DOI:10.1016/j.bjm.2016.07.027 |

| [45] |

Kumari S, Regar RK, Manickam N. Improved polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon degradation in a crude oil by individual and a consortium of bacteria[J]. Bioresource Technology, 2018, 254: 174-179. DOI:10.1016/j.biortech.2018.01.075 |

| [46] |

Wang HZ, Lou J, Gu HP, et al. Efficient biodegradation of phenanthrene by a novel strain Massilia sp. WF1 isolated from a PAH-contaminated soil[J]. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 2016, 23(13): 13378-13388. DOI:10.1007/s11356-016-6515-6 |

| [47] |

Faramarzi MA, Fazeli M, Tabatabaei Yazdi M, et al. Optimization of cultural conditions for production of chitinase by a soil isolate of Massilia timonae [J]. Biotechnology, 2009, 8(1): 93-99. DOI:10.3923/biotech.2009.93.99 |

| [48] |

Han BQ, Yi JL, Cai WD, et al. Fermentation conditions of a chitinase-producing strain, isolation and purification and characterization of the chitinase[J]. Periodical of Ocean University of China, 2010, 40(10): 57-62, 74. (in Chinese) 韩宝芹, 伊金玲, 蔡文娣, 等. 产甲壳素酶菌株的发酵条件、酶的分离纯化及酶学性质研究[J]. 中国海洋大学学报, 2010, 40(10): 57-62, 74. |

| [49] |

Liu L, Wang SC, Peng WF, et al. Identification, genome sequence and production of polysaccharide hydrolases of Massilii eurypsychrophila 709[A]//Abstract Books of Eleventh China Symposium on Enzyme Engineering[C]. Wuhan: Enzyme Engineering Committee of China Society of Microbiology, Hubei University, Wuhan Xinhua Yang Biological Co., Ltd., Angel Yeast Co., Ltd., 2017: 1 (in Chinese) 刘璐, 汪声晨, 彭文舫, 等. Massili a eurypsychrophila 709的鉴定、基因组测序及几种多糖水解酶产生情况分析[A]//第十一届中国酶工程学术研讨会论文摘要集[C].武汉: 中国微生物学会酶工程专业委员会,, 2017: 1 |

| [50] |

Konzen M, De Marco D, Cordova CAS, et al. Antioxidant properties of violacein: Possible relation on its biological function[J]. Bioorganic and Medicinal Chemistry, 2006, 14(24): 8307-8313. DOI:10.1016/j.bmc.2006.09.013 |

| [51] |

Hashimi SM, Xu TF, Wei MQ. Violacein anticancer activity is enhanced under hypoxia[J]. Oncology Reports, 2015, 33(4): 1731-1736. DOI:10.3892/or.2015.3781 |

| [52] |

Sasidharan A, Sasidharan NK, Amma DB, et al. Antifungal activity of violacein purified from a novel strain of Chromobacterium sp. NⅡST (MTCC 5522)[J]. Journal of Microbiology, 2015, 53(10): 694-701. DOI:10.1007/s12275-015-5173-6 |

| [53] |

Suryawanshi RK, Patil CD, Borase HP, et al. Towards an understanding of bacterial metabolites prodigiosin and violacein and their potential for use in commercial sunscreens[J]. International Journal of Cosmetic Science, 2015, 37(1): 98-107. DOI:10.1111/ics.2015.37.issue-1 |

| [54] |

Agate L, Beam D, Bucci C, et al. The search for violacein-producing microbes to combat Batrachochytrium dendrobatidis : A collaborative research project between secondary school and college research students[J]. Journal of Microbiology and Biology Education, 2016, 17(1): 70-73. DOI:10.1128/jmbe.v17i1.1002 |

| [55] |

Dodou HV, de Morais Batista AH, Sales GWP, et al. Violacein antimicrobial activity on Staphylococcus epidermidis and synergistic effect on commercially available antibiotics[J]. Journal of Applied Microbiology, 2017, 123(4): 853-860. DOI:10.1111/jam.2017.123.issue-4 |

| [56] |

Agematu H, Suzuki K, Tsuya H. Massilia sp. BS-1, a novel violacein-producing bacterium isolated from soil[J]. Bioscience, Biotechnology, and Biochemistry, 2011, 75(10): 2008-2010. DOI:10.1271/bbb.100729 |

| [57] |

Yoon SH, Baek HJ, Kwon SW, et al. Production of violacein by a novel bacterium, Massilia sp. EP15224 strain[J]. Korean Journal of Microbiology and Biotechnology, 2014, 42(4): 317-323. DOI:10.4014/kjmb.1410.10006 |

| [58] |

Myeong NR, Seong HJ, Kim HJ, et al. Complete genome sequence of antibiotic and anticancer agent violacein producing Massilia sp. strain NR 4-1[J]. Journal of Biotechnology, 2016, 223: 36-37. DOI:10.1016/j.jbiotec.2016.02.027 |

| [59] |

Keskin G, Kızıl G, Bechelany M, et al. Potential of polyhydroxyalkanoate (PHA) polymers family as substitutes of petroleum based polymers for packaging applications and solutions brought by their composites to form barrier materials[J]. Pure and Applied Chemistry, 2017, 89(12): 1841-1848. DOI:10.1515/pac-2017-0401 |

| [60] |

Zhang DF, Ma QY, Yin TM, et al. The third generation sequencing technology and its application[J]. China Biotechnology, 2013, 33(5): 125-131. (in Chinese) 张得芳, 马秋月, 尹佟明, 等. 第三代测序技术及其应用[J]. 中国生物工程杂志, 2013, 33(5): 125-131. |

| [61] |

dos Santos FC, Barbosa-Tessmann IP. Recombinant expression, purification, and characterization of a cyclodextrinase from Massilia timonae [J]. Protein Expression and Purification, 2019, 154: 74-84. DOI:10.1016/j.pep.2018.08.013 |

| [62] |

Gudeta DD, Bortolaia V, Amos G, et al. The soil microbiota harbors a diversity of carbapenem-hydrolyzing β-lactamases of potential clinical relevance[J]. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy, 2016, 60(1): 151-160. DOI:10.1128/AAC.01424-15 |

| [63] |

Xu B, Dai LM, Li JJ, et al. Molecular and biochemical characterization of a novel xylanase from Massilia sp. RBM26 isolated from the feces of Rhinopithecus bieti [J]. Journal of Microbiology and Biotechnology, 2016, 26(1): 9-19. |

| [64] |

Xu XH, Liu XM, Zhang L, et al. Bioaugmentation of chlorothalonil-contaminated soil with hydrolytically or reductively dehalogenating strain and its effect on soil microbial community[J]. Journal of Hazardous Materials, 2018, 351: 240-249. DOI:10.1016/j.jhazmat.2018.03.002 |

| [65] |

Gu HP, Lou J, Wang HZ, et al. Biodegradation, biosorption of phenanthrene and its trans-membrane transport by Massilia sp. WF1 and Phanerochaete chrysosporium [J]. Frontiers in Microbiology, 2016, 7: 38. |

| [66] |

Lei LP, Xia ZY, Liu XZ, et al. Occurrence and variability of tobacco rhizosphere and phyllosphere bacterial communities associated with nicotine biodegradation[J]. Annals of Microbiology, 2015, 65(1): 163-173. DOI:10.1007/s13213-014-0847-6 |

2019, Vol. 46

2019, Vol. 46