扩展功能

文章信息

- 王颖, 余昀, 刘燕群, 陈晓莉

- WANG Ying, YU Yun, LIU Yan-Qun, CHEN Xiao-Li

- 孕晚期孕妇肠道菌群与孕期体重增长的相关性

- Association between maternal gestational weight gain and gut microbiota at late pregnancy

- 微生物学通报, 2019, 46(1): 151-161

- Microbiology China, 2019, 46(1): 151-161

- DOI: 10.13344/j.microbiol.china.180466

-

文章历史

- 收稿日期: 2018-06-09

- 接受日期: 2018-07-20

- 网络首发日期: 2018-08-17

随着生活水平日渐提高以及对妊娠期营养认识的不足,肥胖妇女妊娠和妊娠期体重增长过度的孕妇日益增多,而且这种趋势已经在全球范围内流行[1-2]。孕期体重增长过度对子代有着深远影响,短期能增加巨大儿发生率、胎粪吸入综合征和新生儿高胆红素血症风险[3-4],远期能引起儿童代谢综合征及儿童肥胖等[5]。目前大量研究表明,数量众多、种类丰富的人体肠道菌群与人体互利共生、相互影响[6-7],肠道菌群与糖尿病、肥胖、消化道疾病等慢性疾病的发生密切相关。母亲的肠道菌群稳态失衡,能够通过羊水、胎盘、脐带血等途径发生母婴传递[8-11],将这种不平衡状态传递给子代[12]。因此,研究孕期体重增长对孕晚期孕妇肠道菌群的影响尤为重要。本研究通过收集62位孕晚期孕妇的粪便,运用MiSeq高通量测序技术对样品中16S rRNA基因V3−V4区序列进行测序,分析其肠道菌群多样性和结构组成,结合相关问卷收集母亲孕前体力活动水平、孕前体质指数(Body mass index,BMI)、孕次、产次、受教育水平和年龄等数据,分析影响孕期体重增长(Geatational weight gain,GWG)的重要因素,明确体重增长过度对孕妇肠道菌群的影响,以期为妊娠期肥胖干预提供新的思路。

1 材料与方法 1.1 建立队列2016年8月至2017年2月,在武汉市某三甲医院门诊采用方便抽样的方法在前来孕期检查的孕妇中建立母婴出生队列。纳入标准为:居住地为武汉市,并计划在该医院进行分娩的孕晚期(孕28−40周)妇女;排除标准为:(1)孕期患有合并症和并发症;(2)孕期进行抗生素治疗;(3)双胎及以上;(4)有认知功能障碍。向孕妇发放知情同意书,征得其同意后采集其粪便样本。根据2009年美国国立医学会孕期增重指南[13],将最终纳入的62位孕妇分为3组:孕期体重增长过低(N=9),孕期体重增长正常(N=27),孕期体重增长过度(N=26)。

1.2 数据收集粪便样本的采集及保存过程为:经过孕妇及其家属同意后,采集其孕晚期(36.82±2.19孕周)粪便样本,每样3份,采集后放入保温盒中(4 ℃)约2 h,然后转入−80 ℃保存,直至测序。

一般人口社会学资料及相关问卷收集:在孕妇进入医院待产时,向孕妇发放自制问卷,主要获得孕妇的一般社会学资料,包括年龄、教育水平、孕前体重、孕期体重增长、孕次、产次和孕前体力活动水平等。

1.3 主要仪器和试剂DNA抽提试剂盒,Omega公司;PCR仪,Applied Biosystems公司;PCR产物回收试剂盒,Axygen公司;PCR产物检测定量系统,Promega公司;MiSeq文库构建试剂和测序仪器,Illumina公司。

1.4 肠道菌群基因组DNA抽提与测序使用试剂盒完成基因组DNA抽提后,利用1%琼脂糖凝胶电泳检测抽提的基因组DNA。根据文献[14]选择引物,扩增区域为V3−V4,引物序列为338FC5′-ACTCCTACGGGAGGCAGCAG-3′)和806R (5′-GGACTACHVGGGTWTCTAAT-3′。PCR反应体系(20 µL):5

孕妇一般社会学资料和孕期体重增长水平,采用卡方和维尔克森秩和检验(Wilcoxon rank sum test)检验两组数据是否有差异。在肠道菌群α多样性和物种组成的分析中,采用一般线性模型中的单变量分析(Univariate analysis of general liner model)控制混杂因素。因孕期体重增长过低一组样本量少,本研究重点阐释孕期体重增长正常和孕期体重增长过度孕妇孕晚期肠道菌群的差异。

孕妇肠道菌群α多样性在OTU水平上采用Shannon多样性指数和Simpson多样性指数,用来估算样本中微生物多样性。Shannon值越大说明群落多样性越高,Simpson值越大说明群落多样性越低。采用一般线性模型中的单变量分析将孕前体质指数和年龄作为协变量,同时也将其孕前体力活动、孕妇孕次、产次、受教育水平放入模型来控制混杂因素。

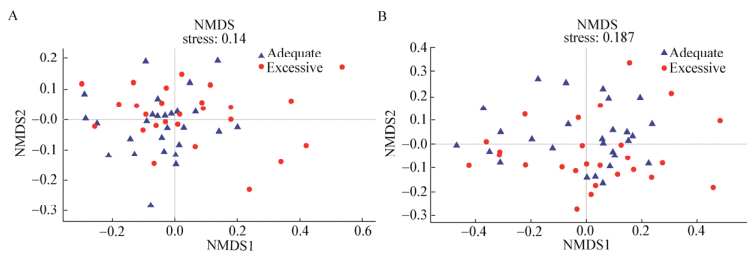

孕妇肠道菌群β多样性采用Bray-curtis和Binary-jaccard两种距离矩阵在OTU水平上进行非度量多维尺度分析(Non-metric multidimensional scaling analysis,NMDS),用样本点的距离表示样本之间的差异,Stress值用来表示此次检验与真实情况的拟合度,通常情况下Stress < 0.2即表示此图形有一定的解释意义。Adonis分析用来判断分组因素对样本差异的解释度。

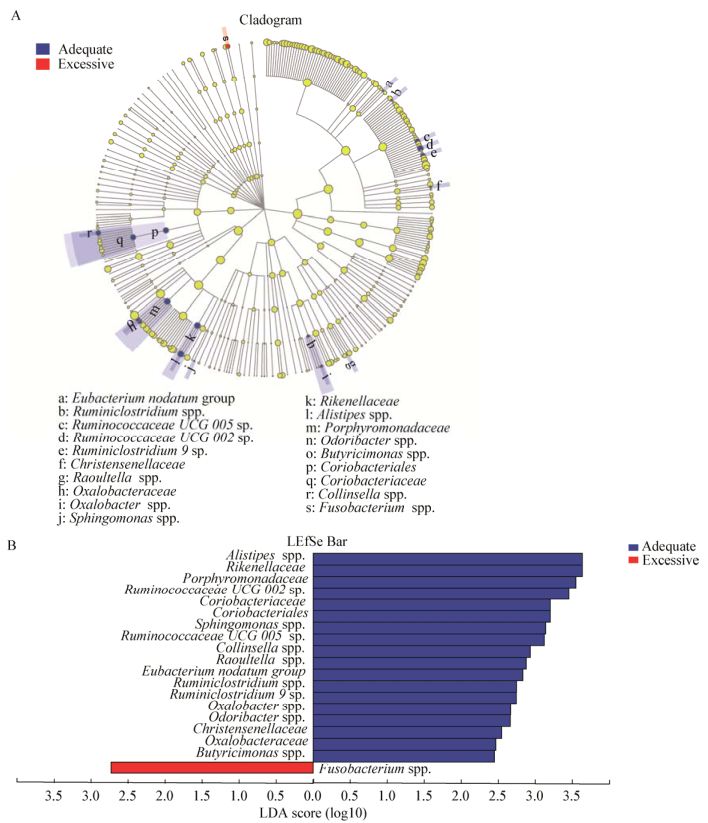

孕妇肠道菌群组成与差异分析采用LEfSe多级物种差异判别,从门到属水平上区别孕期体重增长正常和孕期体重增长过度两组孕妇孕晚期肠道菌群丰度的差异。该软件首先使用非参数因子克鲁斯卡尔–沃利斯秩和验检找到与丰度有显著性差异的类群。最后采用线性判别分析(Linear discriminant ainalysis,LDA)来估算每个组分(物种)丰度对差异效果影响的大小。此外,运用随机森林[15]的方法在属水平上判别对孕期体重增长影响最重要的物种,并计算出每个物种的影响值。对有显著差异且影响力大的物种采用一般线性模型中的单变量分析(Univariate analysis of general liner model)控制混杂因素。

采用SPSS 20.0和QIME V1.9.0进行数据分析,P值小于0.05表明有统计学差异。

2 结果与分析 2.1 测序序列测序共获得2 219 265序列,826个OTU,Good’s coverage为99.73%,表明测序深度足够,本次测序结果可以代表样本的真实情况。

2.2 α多样性孕期体重增长正常组孕妇孕晚期肠道菌群多样性显著高于孕期体重增长过度组(表 1)。在一般线性模型中,控制孕妇孕前体力活动水平、孕前BMI、孕次、产次、年龄和教育水平,孕期体重增长正常组Shannon指数仍然显著高于孕期体重增长过度组(表 2)。

| Items | Total (N=62) N (%)/Median (IQR) | Adequate (N=27) N (%)/Median (IQR) | Excessive (N=26) N (%)/Median (IQR) | P value |

| 年龄Maternal age | 30.13 (27.01−33.25) | 30.45 (26.56−34.34) | 29.31 (26.6−32.02) | 0.14 |

| 孕次Gestation | 0.86 | |||

| 1 | 40 (64.5%) | 17 (63%) | 17 (65.4%) | |

| 2 | 15 (24.2%) | 7 (25.9%) | 6 (23.1%) | |

| 3 | 6 (9.7%) | 2 (7.4%) | 3 (11.5%) | |

| 4 | 1 (1.6%) | 1 (3.7%) | 0 | |

| 产次Parity | 0.27 | |||

| 0 | 44 (71%) | 17 (63%) | 20 (76.9%) | |

| 1 Prior child | 18 (29%) | 10 (37%) | 6 (23.1%) | |

| 受教育水平Maternal education | 0.15 | |||

| < 12 a | 4 (6.5%) | 3 (11.1%) | 0 (0) | |

| 12 a | 42 (67.8%) | 12 (44.4%) | 22 (84.6%) | |

| > 12 a | 16 (25.8%) | 12 (44.4%) | 4 (15.4%) | |

| 孕前BMI水平 Pre-pregnancy BMI category |

0.14 | |||

| 过低Underweight | 11 (17.7%) | 8 (29.6%) | 2 (7.7%) | |

| 正常Normal | 47 (75.8%) | 19 (70.4%) | 21 (80.8%) | |

| 超重Overweight | 4 (6.5%) | 0 (0) | 3 (11.5%) | |

| 孕前体力活动水平 Pre-pregnancy physical activity status |

0.17 | |||

| 久坐Sedentary | 31 (50%) | 16 (59.3%) | 10 (38.5%) | |

| 规律运动Regularly | 31 (50%) | 11 (40.7%) | 16 (61.5%) | |

| 孕周Gestational week | 39.26 (37.8−40.72) | 39.51 (38.53−40.49) | 39.69 (38.78−40.6) | 0.50 |

| Alpha diversity | ||||

| Shannon index | 3.34 (3.84−2.84) | 3.44 (4.0−2.88) | 3.16 (3.59−2.73) | 0.02 |

| Simpson index | 0.09 (0.03−0.15) | 0.09 (0.17−0.01) | 0.11 (0.17−0.05) | 0.02 |

| Items | Shannon index (95%, CI) | P value | Simpson index (95% CI) | P value |

| 截距Intercept | 2.52 (0.48, 4.56) | 0.02 | 0.250 (−0.31, 0.53) | 0.08 |

| 孕期体重增长GWG | 0.30 (0.01, 0.589) | 0.04 | −0.280 (−0.07, 0.01) | 0.16 |

| 孕前BMI Pre-BMI | 0.03 (0.17, 0.01) | 0.27 | −0.003 (−0.01, 0.01) | 0.46 |

| 孕前体力活动水平Pre-PAa | 0.16 (0.17, 0.05) | 0.29 | 0.030 (−0.01, 0.07) | 0.19 |

| 孕次Gestation | 0.26 (−0.11, 0.63) | 0.16 | −0.040 (−0.09, 0.01) | 0.12 |

| 产次Parity | −0.29 (−0.76, 0.19) | 0.23 | 0.010 (−0.06, 0.07) | 0.83 |

| 年龄Maternal age | 0.01 (−0.57, 0.06) | 0.96 | −0.002 (−0.01, 0.01) | 0.59 |

| 注:a:孕期体力活动水平. Note:a: Pre-pregnancy physical activity. |

||||

为进一步了解孕期体重增长正常和孕期体重增长过度两组肠道菌群结构差异,采用Bray-curtis和Binary-jaccard两种距离矩阵NMDS分析方法,Bray-curtis只考虑物种丰度(Stress=0.14;Adonis:R2=0.03,P=0.13;图 1A),Binary-jaccard只考虑物种是否存在(Stress=0.187;Adonis:R2=0.03,P=0.02;图 1B)。当只考虑物种是否存在时,两组肠道菌群分布有轻微差异,差异具有统计学意义。

|

| 图 1 基于OTU水平的NMDS分析 Figure 1 NMDS based on the relative abundance of OTUs Note: A: Bray-curtis; B: Binary-jaccard. |

|

|

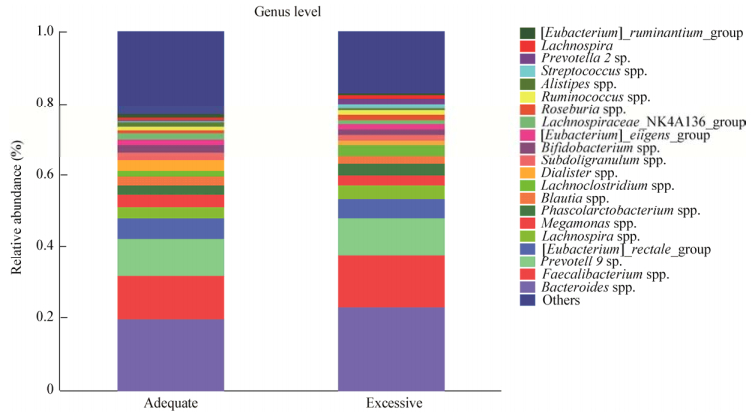

孕期体重增长正常和体重增长过度孕晚期妇女的肠道菌群组成见图 2,在属水平上按照相对丰度从高到低依次是Bacteroides spp. (19.82%;23.37%)、Faecalibacterium spp. (12%;14.46%)、Prevotella 9 sp. (10.53%;10.12%)。

|

| 图 2 孕期体重正常增长和增长过度两组群落组成(属水平) Figure 2 Community compositions on genus level |

|

|

通过LEfSe物种差异判别(图 3A),从门到属共有19种差异物种,采用线性判别分析(LDA),用LDA sore来估算每个组分(物种)丰度对差异效果影响的大小,分值越高,丰度越高,影响越大(图 3B)。通过随机森林,综合各种因素,找出两组肠道菌群组成差异有关的菌群,并按重要性排名。结合这两种分析方式,共筛选出5个属,分别为Alistipes spp.、Eubacterium-nodatum group spp.、Oxalobacter spp.、Raoultella spp.和Odoribacter spp.,这5个属为重要性排名前10的物种,且两组间差异显著,均在孕期体重增长过度组中丰度较高(表 3)。其中,Alistipes spp.不仅在所有有差异的物种中丰度最高,也是影响力最大的,通过一般线性模型中的单变量分析,将孕前BMI、孕前体力活动水平、孕次、产次、年龄和受教育水平纳入模型,仍然只有Alistipes spp.丰度差异具有统计学意义(F=6.71,P=0.01;β=157.2,95% CI35.02,279.39,P=0.01)。此外,LEfSe多级物种差异判别结果显示,仅Fusobacterium spp.在孕期体重增长过度组丰度显著高于孕期体重增长正常组。但通过随机森林分析发现,Fusobacterium spp.对两组差异的影响很小(Variable importance,VI=0.29)。

| 物种名称 Species name |

组别* Group* | LDA值 LDA value |

P值 P value |

重要性 VI |

相对丰度 Relative abundance (%) |

| Alistipes | Adequate | 3.63 | < 0.001 | 5.85 | 0.932 |

| Eubacterium_nodatum_group | Adequate | 2.83 | 0.010 | 2.77 | 0.002 |

| Oxalobacter | Adequate | 2.67 | 0.010 | 2.67 | 0.006 |

| Raoultella | Adequate | 2.88 | 0.040 | 2.11 | 0.001 |

| Odoribacter | Adequate | 2.66 | 0.010 | 2.07 | 0.115 |

| 注:*:在该组中丰度较高. Note:*:More abundant in the group. |

|||||

|

| 图 3 LEfSe多级物种差异判别结果 Figure 3 Results of LEfSe 注:A:不同颜色节点表示在对应组别中显著富集,且对组间差异存在显著影响的微生物类群;蓝色节点代表体重正常增长组,红色节点代表体重过度增长组,淡黄色节点表示在两组中均无显著差异,或对组间差异无显著影响的微生物类群.节点直径越大代表物种丰度越高,不同圆圈代表不同生物学水平,从内到外依次是门、纲、目、科、属. B:LDA判别柱形图统计两组中有显著作用的微生物类群,通过LDA分析(线性判别分析)获得的LDA分值,LDA分值越大,代表物种丰度对差异效果影响越大,在分析时LDA阈值设置为2. Note: A: Taxonomic representation of statistically and biologically consistent differences between adequate and excessive groups. Differences are represented by the color of the most abundant genus (red indicates excessive group; yellow, non-significant; and green, adequate group). The diameter of each circle is proportional to taxon abundance. From inside to outside circle indicate the phylum to genus level in turns. B: Histogram of the linear discriminant analysis (LDA) scores for differentially abundant genera. The threshold on the logarithmic LDA score for discriminative features was set to 2.0, the larger the LDA score, the greater influence of species abundance on the difference between two groups. |

|

|

肠道菌群是人体的第二个基因组,也是额外的内分泌器官,慢性病是如今世界上造成死亡的最主要原因,许多慢性病与肠道菌群失调相关。代谢系统疾病中,Ⅰ型糖尿病患者与正常的健康人群相比,其肠道菌群多样性和稳定性降低,菌群组成中拟杆菌门显著增加,丁酸盐产生菌缺乏[16]。Ⅱ型糖尿病患者中,肠杆菌[17]、气单胞菌属、脱硫弧菌属丰度显著升高,三种菌具有氧化酶活性,并可进行葡萄糖发酵,与糖尿病的发病密切相关[18]。此外肠道菌群在炎性肠病、多发性硬化症、类风湿性关节炎、哮喘与过敏性疾病等慢性炎症疾病中发挥重要作用,能够将人体不能消化的膳食纤维和碳水化合物转化为可利用的短链脂肪酸,并参与维生素的合成与释放[19]。

全球疾病负担(Global burden of disease,GBD)研究结果[20]提示,全球性肥胖流行逐渐恶化。在肥胖人体中,其肠道菌群与肠道局部组织相互作用,促进能量吸收,改变肠内分泌细胞释放的活性分子,削弱肠道屏障,重编结肠基因表达,诱发低度炎症,肠道菌群多样性降低,进而驱动肥胖的发展[21]。

在本研究中,与正常增长孕妇相比,孕期体重增长过度的孕妇肠道菌群多样性显著降低。Koren等[22]研究发现,在整个妊娠期间,随着孕周的增加孕妇的肠道菌群多样性会降低。这是因为胎儿的增长导致孕妇体内激素水平不断变化,母体各个器官和系统在生理上的改变引起体内微生物寄居环境的变化,如各种微量元素、温度、湿度和pH等,因此孕妇肠道菌群也在不断变化[23-24]。但是,这一正常变化也会受孕妇本身生理状况的影响。Stanislawski等分析了169名妇女产后4 d的肠道菌群,发现孕期体重增长与分娩后4 d的肠道菌群多样性无关,但是孕前肥胖或超重的孕妇分娩后4 d的肠道菌群多样性显著低于孕前体重正常的孕妇[12]。我们的研究则表明,孕晚期孕妇肠道菌群的多样性与孕妇孕前体质指数、年龄、孕次和产次等无关,而过度增长的孕期体重会降低其多样性。导致研究结果不一致的原因可能是分娩后孕妇体内激素水平迅速变化,生理应激状态下的肠道菌群也会随之发生改变。因此,分娩前平静状态下孕晚期孕妇肠道菌群的结构变化需要进一步的研究。但是,大量研究表明,肠道菌群多样性的降低与众多疾病相关,如高血脂症、自闭症、肠道炎性疾病、哮喘等过敏性疾病等[25-28]。此外,肥胖人群的肠道菌群多样性也会显著降低[29],而降低的菌群多样性是否会通过母婴传递,将这种影响传递给子代,则需要进一步研究。

孕期体重增长正常和增长过度的两组孕妇肠道菌群组成中,按照丰度从高到低来看,两组基本一致。当只关注孕妇肠道菌群是否存在时,两组孕妇肠道菌群分布有轻微差异。因此,在我们的研究中,两组孕妇有差异的肠道菌群在丰度上均不高,但却是导致两组差异至关重要的物种。其中,Alistipes spp.在两组孕妇孕晚期肠道菌的组成中作为有差异的物种之一,不仅是影响力最高也是丰度最高的物种,其丰度在孕期体重正常增长的孕妇中显著升高。关于孕期体重增长与肠道菌群的相关性研究结果不尽相同。Stanislawski等[12]的研究表明,孕期体重增长过度的孕妇肠道菌群中Blautia spp.丰度显著升高,而此菌也被证实与肥胖和Ⅱ型糖尿病有关[30-31]。Collado等[32]发现,B. fragilis sp.和Bacteroidetes在孕晚期孕妇肠道菌群中丰度显著升高,Bifidobacterium spp.则会降低。另外一项研究[33]表明,孕期体重过度增长会增加孕中期孕妇肠道菌群中E. coli spp.、C. leptum spp.和Staphylococcus aureus spp.的丰度,同时降低Akkermansia muciniphihi spp.、Bifidobacterium spp.和Bacteroides的丰度。肠道菌群受很多因素的影响,除了遗传因素,其中最重要的还包括饮食、生活行为方式和居住环境等。因此,关于孕期体重增长对肠道菌群的影响,各研究出现不同的结果也不足为奇。

在本研究中,孕期体重增长正常和孕期体重增长过度的两组孕妇肠道菌群组成有显著差异的Alistipes spp.能够产生抗代谢产物Sulfobacin B,Sulfobacin B通过抑制肿瘤坏死因子(Tumor necrosis factor,TNF)和NF-κB的产生,减轻移植物的免疫排斥反应[34-35]。高丰度的Alistipes spp.能够促进小鼠移植皮肤的存活,改善机体生理机能[34]。此外,还有研究发现,Alistipes spp. (ASV_5969)中一个物种Alistipes shahii sp.能够提高机体免疫机能,在小鼠中增强抗肿瘤免疫治疗疗效[36]。最近的一项研究[37]表明,随着年龄的增长,在人体免疫衰老的进程中,Oxalobacter spp.在人体肠道中的丰度会随之降低,Oxalobacter spp.与人体生理功能、免疫功能密切相关。在Oxalobacter spp.中,目前研究最广泛的是Oxalobacter formigenes sp.。Oxalobacter formigenes sp.作为肠道内以草酸为唯一碳源和能源的“专性草酸营养型”草酸降解菌,是预防肾结石形成的有益菌[38]。Oxalobacter spp.作为一种丁酸盐产生菌,其产生的丁酸盐具有抗炎和免疫功能,可以降低心脑血管疾病发生的风险。在孕妇的肠道菌群中,Oxalobacter spp.与妊娠期收缩压及Ⅰ型纤溶酶原激活物抑制因子水平呈负相关[39]。一项动物实验表明,高丰度的Oxalobacter spp.可以减缓肥胖的发生[40]。

此外,研究表明Eubacterium nodatum spp.是牙周炎患者的标志性致病菌[41],在各种类型的牙周炎性疾病中丰度显著升高[42],包括中度牙周炎、无显著特点的早发牙周炎、青少年牙周炎、早发性牙周炎和成人牙周炎。与正常体重牙周炎患者相比,肥胖的慢性牙周炎患者口腔中,Eubacterium nodatum spp.丰度显著增高,但在正常体重患者中,Eubacterium nodatum spp.与腰臀比(Waist-to-hip ratio,WHR)呈正相关[43]。腰臀比是腰围和臀围的比值,是判定中心性肥胖的重要指标,在进化心理学中同时也是预测女性生育力的有效线索。腰臀比小的女性发育较早,而腰臀比大的女性更难怀孕,同时腰臀比反映了女性体内长链多不和脂肪酸的含量,这种脂肪酸对胎儿神经发育至关重要,腰臀比低的女性后代智商相对较高[44]。在本研究中,Eubacterium nodatum spp.在孕期体重增长正常的孕妇肠道中丰度较高,而孕期体重增长正常的孕妇其腰臀比比孕期体重增长过度的孕妇要低,这与上述以往研究结果相反。可能的原因是妊娠时人体激素水平剧烈变化,而且肠道菌群与口腔菌群差别较大,Eubacterium nodatum spp.在妊娠期女性肠道中有可能是一种有益菌,但其具体机制及对后代肠道菌群的影响仍需要进一步研究。目前关于Raoultella spp.的相关研究较少。Raoultella spp.包括Raoultella ornithinolytica sp.、Raoultella planticola sp.和Raoultella terrigena sp.,代表菌种为Raoultella planticola sp.,但其一般存在于植物、土壤和水等环境中,在临床标本(痰液、尿液、伤口分泌物)中较少见[45],仅有的几项人群研究表明,其少量存在于腹泻[46]及易患乳糜泻的高危幼儿[47]的肠道菌群中。因此,Raoultella在孕期体重正常增长的孕晚期孕妇肠道中富集,其机制有待进一步研究。

尽管各研究结果不同,但不可否认的一点是,孕妇孕晚期肠道菌群的结构和组成确实受孕期体重增长的影响,并将这种影响传递给子代。Collado等[48]分析了16个超重和26个正常体重的孕妇及其婴儿1−6月的肠道菌群发现,孕期体重增长过度与6个月婴儿肠道菌群中显著降低的Bifidobacterium spp.和升高的S. aureus spp.有关。而在一项出生队列研究中发现[49],婴儿出生后6个月和12个月肠道中低丰度的Bifidobacterium spp.均与儿童期肥胖相关。而在孕期体重正常增长的孕妇中,丰度显著升高的Alistipes spp.、Eubacterium-nodatum group spp.、Oxalobacter spp.、Raoultella spp.和Odoribacter spp.在子代肠道菌群中是否发生改变,则需要进一步研究。

本研究通过分析62位孕晚期孕妇的肠道菌群,探讨孕期体重增长对肠道菌群多样性、结构和组成的影响。筛选出Alistipes spp.、Eubacterium-nodatum group spp.、Oxalobacter spp.、Raoultella spp.和Odoribacter spp.共5个与孕期体重增长相关性最强的菌群。同时,研究发现,孕期体重增长过度会使孕妇肠道菌群多样性显著降低。本研究只分析了孕晚期肠道菌群与孕期体重增长之间的关系,关于孕期体重增长对孕妇肠道菌群的改变对子代肠道菌群的影响则需要进一步研究。因此,孕期体重管理大样本的长时间母婴出生队列研究显得尤为重要,有助于临床工作者进一步了解孕期体重增长过度孕妇肠道菌群对婴幼儿肠道菌群的影响。通过对孕妇和婴幼儿进行营养干预和饮食指导,建立均衡的肠道菌群,为孕期体重管理和婴幼儿肥胖干预提供新思路。

| [1] |

Devlieger R, Benhalima K, Damm P, et al. Maternal obesity in Europe: where do we stand and how to move forward?: A scientific paper commissioned by the European Board and College of Obstetrics and Gynaecology (EBCOG)[J]. European Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology and Reproductive Biology, 2016, 201: 203-208. |

| [2] |

Nodine PM, Hastings-Tolsma M. Maternal obesity: improving pregnancy outcomes[J]. MCN, The American Journal of Maternal/Child Nursing, 2012, 37(2): 110-115. DOI:10.1097/NMC.0b013e3182430296 |

| [3] |

Schaap MWH, Uilenreef JJ, Mitsogiannis MD, et al. Optimizing the dosing interval of buprenorphine in a multimodal postoperative analgesic strategy in the rat: minimizing side-effects without affecting weight gain and food intake[J]. Laboratory Animals, 2012, 46(4): 287-292. DOI:10.1258/la.2012.012058 |

| [4] |

Stotland NE, Cheng YW, Hopkins LM, et al. Gestational weight gain and adverse neonatal outcome among term infants[J]. Obstetrics & Gynecology, 2006, 108(3 Pt 1): 635-643. |

| [5] |

Gohir W, Ratcliffe EM, Sloboda DM. Of the bugs that shape us: maternal obesity, the gut microbiome, and long-term disease risk[J]. Pediatric Research, 2015, 77(1/2): 196-204. |

| [6] |

Gill SR, Pop M, Deboy RT, et al. Metagenomic analysis of the human distal gut microbiome[J]. Science, 2006, 312(5778): 1355-1359. DOI:10.1126/science.1124234 |

| [7] |

Garcia-Mantrana I, Collado MC. Obesity and overweight: Impact on maternal and milk microbiome and their role for infant health and nutrition[J]. Molecular Nutrition & Food Research, 2016, 60(8): 1865-1875. |

| [8] |

Rautava S, Collado MC, Salminen S, et al. Probiotics modulate host-microbe interaction in the placenta and fetal gut: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial[J]. Neonatology, 2012, 102(3): 178-184. DOI:10.1159/000339182 |

| [9] |

Aagaard KM. Author response to comment on "the placenta harbors a unique microbiome"[J]. Science Translational Medicine, 2014, 6(254): 254lr3. DOI:10.1126/scitranslmed.3010007 |

| [10] |

Zheng J, Xiao XH, Zhang Q, et al. The placental microbiome varies in association with low birth weight in full-term neonates[J]. Nutrients, 2015, 7(8): 6924-6937. DOI:10.3390/nu7085315 |

| [11] |

Jiménez E, Fernández L, Marín ML, et al. Isolation of commensal bacteria from umbilical cord blood of healthy neonates born by cesarean section[J]. Current Microbiology, 2005, 51(4): 270-274. DOI:10.1007/s00284-005-0020-3 |

| [12] |

Stanislawski MA, Dabelea D, Wagner BD, et al. Pre-pregnancy weight, gestational weight gain, and the gut microbiota of mothers and their infants[J]. Microbiome, 2017, 5: 113. DOI:10.1186/s40168-017-0332-0 |

| [13] |

Institute of Medicine. Weight Gain During Pregnancy: Reexamining the Guidelines[M]. Washington, DC: National Academies Press, 2009.

|

| [14] |

Xu N, Tan GC, Wang HY, et al. Effect of biochar additions to soil on nitrogen leaching, microbial biomass and bacterial community structure[J]. European Journal of Soil Biology, 2016, 74: 1-8. DOI:10.1016/j.ejsobi.2016.02.004 |

| [15] |

Breiman L. Random forests[J]. Mach Learn, 2001, 45: 5-32. DOI:10.1023/A:1010933404324 |

| [16] |

Knip M, Siljander H. The role of the intestinal microbiota in type 1 diabetes mellitus[J]. Nature Reviews Endocrinology, 2016, 12(3): 154-167. DOI:10.1038/nrendo.2015.218 |

| [17] |

Wang Y, Luo X, Mao XM, et al. Gut microbiome analysis of type 2 diabetic patients from the Chinese minority ethnic groups the Uygurs and Kazaks[J]. PLoS One, 2017, 12(3): e0172774. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0172774 |

| [18] |

Tsai YH, Huang KC, Huang TJ, et al. Case reports: fatal necrotizing fasciitis caused by Aeromonas sobria in two diabetic patients[J]. Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research, 2009, 467(3): 846-849. DOI:10.1007/s11999-008-0504-0 |

| [19] |

Hand TW, Vujkovic-Cvijin I, Ridaura VK, et al. Linking the microbiota, chronic disease, and the immune system[J]. Trends in Endocrinology & Metabolism, 2016, 27(12): 831-843. |

| [20] |

Gregg EW, Shaw JE. Global health effects of overweight and obesity[J]. New England Journal of Medicine, 2017, 377(1): 80-81. DOI:10.1056/NEJMe1706095 |

| [21] |

Sun LJ, Ma LJ, Ma YB, et al. Insights into the role of gut microbiota in obesity: pathogenesis, mechanisms, and therapeutic perspectives[J]. Protein & Cell, 2018, 9(5): 397-403. |

| [22] |

Koren O, Goodrich JK, Cullender TC, et al. Host remodeling of the gut microbiome and metabolic changes during pregnancy[J]. Cell, 2012, 150(3): 470-480. DOI:10.1016/j.cell.2012.07.008 |

| [23] |

Ursell LK, Clemente JC, Rideout JR, et al. The interpersonal and intrapersonal diversity of human-associated microbiota in key body sites[J]. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology, 2012, 129(5): 1204-1208. DOI:10.1016/j.jaci.2012.03.010 |

| [24] |

Sarvestani SF, Rahmanifar F, Tamadon A. Histomorphometric changes of small intestine in pregnant rat[J]. Veterinary Research Forum, 2015, 6(1): 69-73. |

| [25] |

Walters WA, Xu ZC, Knight R. Meta-analyses of human gut microbes associated with obesity and IBD[J]. FEBS Letters, 2014, 588(22): 4223-4233. DOI:10.1016/j.febslet.2014.09.039 |

| [26] |

Kang DW, Park JG, Ilhan ZE, et al. Reduced incidence of Prevotella and other fermenters in intestinal microflora of autistic children[J]. PLoS One, 2013, 8(7): e68322. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0068322 |

| [27] |

Ege MJ, Mayer M, Normand AC, et al. Exposure to environmental microorganisms and childhood asthma[J]. The New England Journal of Medicine, 2011, 364(8): 701-709. DOI:10.1056/NEJMoa1007302 |

| [28] |

le Chatelier E, Nielsen T, Qin JJ, et al. Richness of human gut microbiome correlates with metabolic markers[J]. Nature, 2013, 500(7464): 541-546. DOI:10.1038/nature12506 |

| [29] |

Sze MA, Schloss PD. Looking for a signal in the noise: revisiting obesity and the microbiome[J]. mBio, 2016, 7(4): e01018-16. |

| [30] |

Egshatyan L, Kashtanova D, Popenko A, et al. Gut microbiota and diet in patients with different glucose tolerance[J]. Endocr Connect, 2016, 5(1): 1-9. |

| [31] |

Kasai C, Sugimoto K, Moritani I, et al. Comparison of the gut microbiota composition between obese and non-obese individuals in a Japanese population, as analyzed by terminal restriction fragment length polymorphism and next-generation sequencing[J]. BMC Gastroenterology, 2015, 15: 100. DOI:10.1186/s12876-015-0330-2 |

| [32] |

Collado MC, Isolauri E, Laitinen K, et al. Distinct composition of gut microbiota during pregnancy in overweight and normal-weight women[J]. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 2008, 88(4): 894-899. DOI:10.1093/ajcn/88.4.894 |

| [33] |

Santacruz A, Collado MC, Garcia-Valdés L, et al. Gut microbiota composition is associated with body weight, weight gain and biochemical parameters in pregnant women[J]. British Journal of Nutrition, 2010, 104(1): 83-92. DOI:10.1017/S0007114510000176 |

| [34] |

Mcintosh CM, Chen LQ, Shaiber A, et al. Gut microbes contribute to variation in solid organ transplant outcomes in mice[J]. Microbiome, 2018, 6: 96. DOI:10.1186/s40168-018-0474-8 |

| [35] |

Maeda J, Nishida M, Takikawa H, et al. Inhibitory effects of sulfobacin B on DNA polymerase and inflammation[J]. International Journal of Molecular Medicine, 2010, 26(5): 751-758. |

| [36] |

Iida N, Dzutsev A, Stewart CA, et al. Commensal bacteria control cancer response to therapy by modulating the tumor microenvironment[J]. Science, 2013, 342(6161): 967-970. DOI:10.1126/science.1240527 |

| [37] |

Shen X, Miao JJ, Wan Q, et al. Possible correlation between gut microbiota and immunity among healthy middle-aged and elderly people in southwest China[J]. Gut Pathogens, 2018, 10: 4. DOI:10.1186/s13099-018-0231-3 |

| [38] |

Tang RQ, Jiang YH, Tan AH, et al. 16S rRNA gene sequencing reveals altered composition of gut microbiota in individuals with kidney stones[J]. Urolithiasis, 2018, 1-12. |

| [39] |

Gomez-Arango LF, Barrett HL, McIntyre HD, et al. Increased systolic and diastolic blood pressure is associated with altered gut microbiota composition and butyrate production in early pregnancy[J]. Hypertension, 2016, 68(4): 974-981. DOI:10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.116.07910 |

| [40] |

Etxeberria U, Hijona E, Aguirre L, et al. Pterostilbene-induced changes in gut microbiota composition in relation to obesity[J]. Molecular Nutrition & Food Research, 2017, 61(1). DOI:10.1002/mnfr.201500906 |

| [41] |

Booth V, Downes J, van den Berg J, et al. Gram-positive anaerobic bacilli in human periodontal disease[J]. Journal of Periodontal Research, 2004, 39(4): 213-220. DOI:10.1111/j.1600-0765.2004.00726.x |

| [42] |

Haffajee AD, Teles RP, Socransky SS. Association of Eubacterium nodatum and Treponema denticola with human periodontitis lesions[J]. Oral Microbiology and Immunology, 2006, 21(5): 269-282. DOI:10.1111/omi.2006.21.issue-5 |

| [43] |

Maciel SS, Feres M, Gonçalves TED, et al. Does obesity influence the subgingival microbiota composition in periodontal health and disease?[J]. Journal of Clinical Periodontology, 2016, 43(12): 1003-1012. DOI:10.1111/jcpe.2016.43.issue-12 |

| [44] |

Lassek WD, Gaulin SJC. Waist-hip ratio and cognitive ability: is gluteofemoral fat a privileged store of neurodevelopmental resources?[J]. Evolution and Human Behavior, 2008, 29(1): 26-34. |

| [45] |

Zhu YJ, Shan XY, Ying HY, et al. Distribution and drug resistance of Raoultella planticola in nosocomial infections[J]. Chinese Journal of Critical Care Medicine (Electronic Edition, in Chinese), 2014, 7(4): 257-260. 朱以军, 单小云, 应华永, 等. 植生拉乌尔菌在院内感染中的分布特点与耐药性研究[J]. 中华危重症医学杂志(电子版), 2014, 7(4): 257-260. |

| [46] |

Amani J, Barjini KA, Moghaddam MM, et al. In vitro synergistic effect of the CM11 antimicrobial peptide in combination with common antibiotics against clinical isolates of six species of multidrug-resistant pathogenic bacteria[J]. Protein & Peptide Letters, 2015, 22(10): 940-951. |

| [47] |

Olivares M, Neef A, Castillejo G, et al. The HLA-DQ2 genotype selects for early intestinal microbiota composition in infants at high risk of developing coeliac disease[J]. Gut, 2015, 64(3): 406-417. DOI:10.1136/gutjnl-2014-306931 |

| [48] |

Collado MC, Isolauri E, Laitinen K, et al. Effect of mother's weight on infant's microbiota acquisition, composition, and activity during early infancy: a prospective follow-up study initiated in early pregnancy[J]. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 2010, 92(5): 1023-1030. DOI:10.3945/ajcn.2010.29877 |

| [49] |

Kalliomäki M, Collado MC, Salminen S, et al. Early differences in fecal microbiota composition in children may predict overweight[J]. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 2008, 87(3): 534-538. DOI:10.1093/ajcn/87.3.534 |

2019, Vol. 46

2019, Vol. 46