扩展功能

文章信息

- 杨美玲, 张霞, 王绍明, 刘鸯, 张丽霞, 赵祥

- YANG Mei-Ling, ZHANG Xia, WANG Shao-Ming, LIU Yang, ZHANG Li-Xia, ZHAO Xiang

- 基于高通量测序的裕民红花根际土壤细菌群落特征分析

- High throughput sequencing analysis of bacterial communities in Yumin safflower

- 微生物学通报, 2018, 45(11): 2429-2438

- Microbiology China, 2018, 45(11): 2429-2438

- DOI: 10.13344/j.microbiol.china.171038

-

文章历史

- 收稿日期: 2017-12-08

- 接受日期: 2018-03-21

菊科红花(Carthamus tinctorius L.)为中国传统道地药材,经多年临床发现,红花具有扩张血管、降血压、抗凝血、抗氧化、消炎镇痛和抗肿瘤等药理作用。红花在全球广泛种植,由于新疆裕民县得天独厚的地理环境和气候条件适合红花生长并且有利于红花良好品质的形成,促使该地区每年红花种植面积均在10 000 hm2以上,成为全国最大的红花种植基地,目前红花也已成为当地农民增收的支柱产业[1]。

近年来,研究者对道地药材的根际微生物展开了初步研究,在以土壤为宿主载体,植物根系与微生物互相作用而形成的微生态系统中,根际微生物通过物质循环、能量转换与宿主相互作用改变药用植物根际土壤酸碱度、氧化还原状况等特性,促进根际土壤有效养分的转换与储存,加快植物根系对养分的吸收,从而提高药材的品质,形成道地性药材[2]。土壤中的微生物在此过程中起非常重要的作用,因此,对红花道地性及其根际微生物的研究显得尤为重要。

随着现代科学技术的发展,具有高通量、高准确度和低成本优势的高通量测序技术已广泛应用于根际微生物的研究中,现已成为研究环境微生物多样性及群落结构差异的重要手段[3-4]。与前人研究红花根际微生物时使用的平板稀释涂布法、单链构象多态性(SSCP)和磷脂脂肪酸(PLFA)法相比,高通量测序技术能更真实全面地反映微生物的群落结构和多样性[5]。本研究采用高通量测序技术分析新疆裕民县山地红花不同生长发育期的根际土壤细菌群落结构,旨在系统了解其细菌多样性,探讨细菌群落与植物生长阶段、土壤环境因子的关系,从而为揭示道地药材“道地性”的本质与规律提供科学依据。

1 材料与方法 1.1 研究区概况本次研究对象为新疆裕民县山地的栽培红花,共选取3块样地(记为样地1、样地2、样地3),地理坐标与海拔高度分别为82°79′46′′E,46°11′19′′N,1 112 m;82°69′76′′E,46°06′42′′N,1 182 m;82°68′54′′E,46°02′93′′N,1 203 m,属大陆性干旱气候,年平均气温6.5 ℃,无霜期156 d左右,年降水量为279.5 mm,且在耕作与植物生长过程中未施用任何肥料。

1.2 样品采集2016年6月18日与2016年7月26日在这3块样地分别采集红花营养生长期根际(记为VR,所采样品分别记为V1R、V2R、V3R)、非根际(VB,所采样品分别记为V1B、V2B、V3B)土壤样品与生殖生长期根际(RR,所采样品分别记为R1R、R2R、R3R)、非根际(RB,所采样品分别记为R1B、R2B、R3B)土壤样品。根际土壤取样采用“抖根法”:先将植物根系从土壤中挖出,抖掉与根系结合松散的土壤,收集与根系紧密结合在0−4 mm范围的土壤作为根际土壤,在采集根际土旁选取没有植物生长的位置采集与根际土相同深度的土壤作为非根际土壤样品。采集红花根际与非根际土壤样品均按“S”形采样方法,随机选取5个点混合样品,取样过程中去除凋落物等有机质。取回鲜土后立即过20目筛并分为两份,一份保存于−80 ℃,用于DNA提取和高通量测序;另一份风干保存,用于测定土壤性质。

1.3 土壤性质的测定风干后的土壤样品进行以下性质分析:pH、电导率、含水率、有机质、全钾、全氮和全磷。土壤性质的测定参考鲍士旦《土壤农化分析》中的测定方法[6],pH和电导率使用奥豪斯测试笔测定,全氮采用半微量开氏法测定,全钾采用火焰光度法测定,全磷采用HClO4-H2SO4法测定,有机质使用外加热法测定。每个土壤指标设置3个重复,使用SPSS 19.0统计学分析软件对土壤性质进行单因素方差分析。

1.4 细菌16S rRNA基因测序 1.4.1 基因组DNA的提取和PCR扩增采用CTAB法对样品的基因组DNA进行提取,之后利用琼脂糖凝胶电泳检测DNA的纯度和浓度,取适量的样品于离心管中,使用无菌水稀释样品至1 ng/μL,每个样品做3个重复。以稀释后的基因组DNA为模板,使用带Barcode的特异引物515F (5′-GTGCCAGCMGCCGCGGTAA-3′)和806R (5′-GGACTACHVGGGTWTCTAAT-3′)对16S rRNA基因的V4高变区片段进行PCR扩增。PCR反应体系:2×Phusion Master Mix 15 µL,2 µmol/L Primer各3 µL,1 ng/µL基因组DNA 7 µL,ddH2O 2 µL。PCR反应条件:98 ℃ 1 min;98 ℃ 10 s,50 ℃ 30 s,72 ℃ 30 s,30个循环;72 ℃ 5 min。PCR产物使用2%浓度的琼脂糖凝胶进行电泳检测,对目的条带使用QIAGEN公司提供的胶回收试剂盒回收产物后进行纯化。使用TruSeq® DNA PCR-Free Sample Preparation建库试剂盒进行文库构建,构建好的文库经过Qubit和Q-PCR定量,文库合格后,使用Illumina HiSeq2500 PE250进行上机测序。

1.4.2 生物信息处理根据Barcode序列和PCR扩增引物序列从下机数据中拆分出各样品数据,截去Barcode和引物序列后使用FLASH (v1.2.7)对每个样品的Reads进行拼接、过滤、去除嵌合体序列,得到有效数据;使用UPARSE (v7.0.1001)将有效序列按照97%的一致性聚类成为OTU (Operational taxonomic unit),根据OTU聚类结果,一方面用Mouthor方法与SILVA的SSUrRNA数据库对每个OTU的代表序列做物种注释,获得分类学信息和各样本在各分类水平上的群落组成,用MUSCLE (v3.8.31)软件进行快速多序列比对后,对样品的数据进行均一化处理。同时,使用QIIME (v1.7.0)软件进行OTU丰度、Alpha多样性计算,以得到样品内物种丰富度和均匀度信息。使用R (v2.15.3)软件绘制PCoA图,然后进行多样性指数与环境因子的相关性分析,得到对群落变化影响较大的环境因子。测序与信息分析由北京诺禾致源科技股份有限公司完成。

1.4.3 主要试剂和仪器Phusion® High-Fidelity PCR Master Mix with GC Buffer,New England Biolabs公司;QIAquick Gel Extraction Kit,QIAGEN公司;GeneJET胶回收试剂盒,Thermo Scientific公司;TruSeq® DNA PCR-Free Sample Preparation、HiSeq2500 PE250仪器,Illumina公司。

2 结果与分析 2.1 土壤性质分析在SPSS统计学软件中使用Duncan分析法对红花各样地土壤样品的土壤性质进行单因素方差分析,结果如表 1所示。从表 1可以看出,土壤pH除在V1B与R2B、V3R、R2R、R1B中无显著差异(P > 0.05)外,在其他各组样品之间均存在显著差异(P < 0.05);含水率在V1B与V2B之间、R1R与R3R、R1B彼此间无显著差异(P > 0.05),此外在其他各样品组之间差异显著(P < 0.05);电导率在V1R、V2R、V3R、R3B样品组之间和V3B、R1R、R2R样品组之间无显著性差异(P > 0.05),而电导率在其他样品组之间皆存在显著性差异(P < 0.05);全钾含量除在R2R、R3R与V2R、V3R、V3B、R2B之间存在显著性差异外(P < 0.05),与其他各样品组间无显著差异(P > 0.05),且其他各样品组之间也无显著差异(P > 0.05);此外,其他土壤性质在各样品组之间的分布情况也不相同,具体情况见表 1。

| 样品分组 Group name |

pH | EC (μs/cm) |

SM (%) |

TN (g/kg) |

TK (g/kg) |

TP (g/kg) |

OM (g/kg) |

| V1R | 7.47±0.008 8i | 134.43±0.52e | 15.28±0.14e | 1.92±0.09ab | 62.22±0.66abc | 0.18±0.027 0de | 33.84±1.80ab |

| V2R | 7.77±0.006 7e | 139.07±0.69e | 18.53±0.09b | 1.79±0.21abc | 63.29±1.54ab | 0.18±0.013 4d | 31.54±0.65abc |

| V3R | 7.99±0.005 8c | 139.33±0.17e | 16.16±0.09d | 1.17±0.05de | 64.60±0.95ab | 0.23±0.027 5cd | 34.56±2.49a |

| V1B | 7.95±0.003 3d | 202.33±1.20b | 17.37±0.06c | 1.60±0.17bcd | 64.03±1.34ab | 0.10±0.004 0e | 28.17±1.28abc |

| V2B | 7.74±0.006 7f | 180.27±0.30c | 17.37±0.10c | 1.12±0.14e | 62.22±0.44abc | 0.22±0.062 6cd | 19.59±1.99de |

| V3B | 7.64±0.003 3g | 108.37±0.32f | 10.38±0.08f | 0.64±0.07f | 65.34±2.47a | 0.18±0.020 0d | 11.39±2.09f |

| R1R | 8.16±0.003 3a | 117.10±11.47f | 9.47±0.02g | 1.78±0.05abc | 62.44±0.92abc | 0.34±0.009 3ab | 26.71±2.57bc |

| R2R | 8.01±0.006 7c | 107.30±0.31f | 8.03±0.04i | 2.17±0.32a | 59.39±0.86c | 0.28±0.021 5bc | 25.02±3.41cd |

| R3R | 7.72±0.003 3h | 82.00±0.15g | 7.70±0.03g | 1.80±0.24abc | 59.51±0.23c | 0.37±0.008 7a | 28.83±1.04abc |

| R1B | 8.01±0.011 5c | 241.67±0.33a | 9.31±0.06g | 1.33±0.09cde | 62.17±1.39abc | 0.32±0.005 8ab | 25.30±1.83cd |

| R2B | 7.96±0.008 8d | 151.53±0.35d | 26.33±0.04a | 1.62±0.06bcd | 64.06±0.38ab | 0.28±0.030 3bc | 18.28±3.96de |

| R3B | 8.05±0.003 3b | 144.03±0.20de | 8.77±0.10h | 0.86±0.01ef | 61.25±0.25bc | 0.37±0.001 8a | 13.07±1.04ef |

| 注:EC:电导率;SM:含水率;TN:全氮;TK:全钾;TP:全磷;OM:有机质.同列不同小写字母表示不同样品分组之间差异显著(P < 0.05). Note: EC: Conductivity; SM: Moisture content; TN: Total nitrogen; TK: Total potassium; TP: Total phosphorus; OM: Organic matter. Different lowercase letters within the same column indicate significant differents between different sample groups (P < 0.05). |

|||||||

物种多样性是衡量群落生物组成的重要指标,用来反映群落内物种的多少,能够客观地比较各样品的相似性及差异性。36个土壤样品的高通量测序共获得2 694 274条高质量序列,平均长度为253.22 bp。以97%相似度划分,共得到10 303个OTU。表 2为红花土壤细菌丰度和多样性的单因素方差分析结果,从表 2中得知各样品文库的覆盖率(Coverage)均大于98.47%,说明各样地的微生物物种信息得到了充分的体现,本次测序结果能够代表裕民县山地红花土壤细菌群落的真实情况。从表 2中发现丰富度指数Chao1、多样性指数Shannon、样品覆盖率Coverage在各组样品之间不存在显著差异(P > 0.05),说明两个生长阶段及各样地之间的红花土壤微生物的丰富程度和多样性情况基本一致。

| 样品分组 Sample group |

丰富度指数 Chao1 |

多样性指数 Shannon |

覆盖率 Coverage (%) |

| V1R | 3 679.36±526.43a | 9.23±0.36a | 98.57±0.28a |

| V2R | 3 694.84±488.61a | 9.32±0.27a | 98.70±0.26a |

| V3R | 3 781.94±395.61a | 9.34±0.30a | 98.60±0.15a |

| V1B | 3 946.04±475.28a | 9.54±0.29a | 98.47±0.24a |

| V2B | 4 081.27±404.14a | 9.56±0.28a | 98.47±0.15a |

| V3B | 3 970.32±392.96a | 9.34±0.27a | 98.47±0.19a |

| R1R | 3 831.38±378.24a | 9.45±0.22a | 98.50±0.20a |

| R2R | 3 797.45±380.06a | 9.22±0.29a | 98.57±0.15a |

| R3R | 3 842.13±375.80a | 9.50±0.23a | 98.60±0.21a |

| R1B | 3 536.13±244.72a | 9.38±0.21a | 98.70±0.12a |

| R2B | 3 729.85±267.67a | 9.17±0.25a | 98.57±0.09a |

| R3B | 3 471.60±47.54a | 9.29±0.11a | 98.77±0.03a |

| 注:同列不同小写字母表示不同样品分组之间差异显著(P < 0.05). Note: Different lowercase letters within the same column indicate significant differents between different sample groups (P < 0.05). |

|||

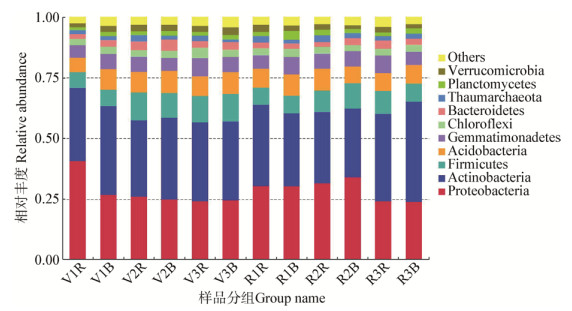

36个红花土壤样品的10 303个OTU分属于47门102纲201目381科738属405种。图 1为3个样地不同生长阶段根际与非根际土壤细菌门水平下的分类,各土壤样品间的细菌群落组成相似,除了未确定种属的其他菌类,相对丰度较高的前10个菌门分别为放线菌门(Actinobacteria,32.9%)、变形菌门(Proteobacteria,28.7%)、厚壁菌门(Firmicutes,9.0%)、酸杆菌门(Acidobacteria,8.0%)、芽单胞菌门(Gemmatimonadetes,6.2%)、绿弯菌门(Chloroflexi,3.0%)、拟杆菌门(Bacteroidetes,2.8%)、奇古菌门(Thaumarchaeota,2.0%)、疣微菌门(Verrucomicrobia,2.3%)、浮霉菌门(Planctomycetes,1.9%)。由图 1得知,变形菌门和放线菌门是裕民县山地红花土壤的优势菌群,且各样地土壤样品的相对丰度之间存在差异。

|

| 图 1 红花土壤细菌门水平分类 Figure 1 Bacterial classification of safflower soil in phyla lever |

|

|

图 2为红花不同生长阶段根际与非根际土壤细菌属水平上的物种聚类热图,图中展示的是相对丰度排名前35的菌属,红蓝色代表菌属的丰度,越偏向红色丰度越高,越偏向蓝色丰度越低。进一步从属水平研究发现,不同生长阶段乃至不同样地之间的细菌群落丰度差异明显,由图 2可知,V1R中丰度较大的属有鞘氨醇单胞菌属(Sphingomonas)、乳酸菌属(Lactobacillus)、布鲁氏菌属(Brucella)、叶杆菌属(Phyllobacterium)、根瘤菌属(Rhizobium)、Bosea、慢生根瘤菌属(Bradyrhizobium)、藤黄色杆菌属(Luteibacter)和气单胞菌属(Aeromonas),V2R中芽孢杆菌属(Bacillus)和Bryobacter丰度相对较高,V3R中芽单胞菌属(Gemmatimonas)丰度相对较高,V1B中丰度较大的是Candidatus_Entotheonella,V2B中丰度较高的有小杆菌属(Dialister)、Prevotella_1和链球菌属(Streptococcus),V3B中盐单胞菌属(Halomonas)丰度相对较高;在R1R中丰度相对较高的菌属有Candidatus_Nitrososphaera和Gaiella,在R2R中丰度较高的是Candidatus_Nitrososphaera和寡养单胞菌属(Stenotrophomonas),R3R中链霉菌属(Streptomyces)、芽单胞菌属(Gemmatimonas)、Haliangium丰度相对较高,R1B中丰度相对较高的是寡养单胞菌属(Stenotrophomonas),在R2B中丰度较高的有Microvirga、斯科曼氏球菌属(Skermanella)、Acidibacter,在R3B中节杆菌属(Arthrobacter)、Steroidobacter、假诺卡氏菌属(Pseudonocardia)丰度相对较高。参照右上角图例,发现极大部分菌属被聚类到变形菌门和放线菌门,个别菌属被聚类到酸杆菌门、厚壁菌门、芽单胞菌门、奇古菌门和疣微菌门。

|

| 图 2 红花土壤细菌群落基于属水平上的聚类分析 Figure 2 Soil bacterial community cluster analysis of safflower based on genus level |

|

|

通过对红花2个生长阶段的3块不同样地的土壤细菌群落进行主坐标分析(PCoA) (图 3),将多维的土壤微生物变量降维成2个变量,其中第一主坐标(PC1)的贡献率为27.68%,第二主坐标(PC2)的贡献率为20.82%,二者累积贡献率为48.50%。从图 3中可以看出,除了红花2个生长阶段的土壤样品距离较远外,相同生长阶段的3块样地的土壤样品之间也相距较远,说明红花各样地之间的微生物群落构成的差异较为明显,与图 2结果一致。

|

| 图 3 红花土壤细菌群落主坐标分析 Figure 3 Principal coordinates analysis of safflower soil bacterial |

|

|

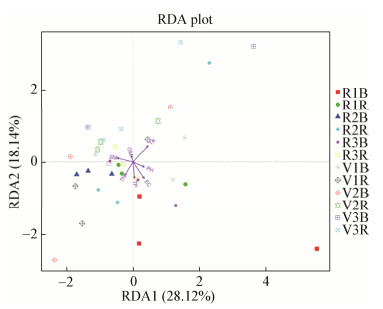

在进行土壤性质与细菌群落相关性分析前对细菌的信息进行DCA分析,根据最大梯度(0.58)采用基于线性模型的排序方法——冗余分析(RDA)。RDA显示主要的土壤性质与细菌群落之间的关系,第一、第二轴分别解释了数据中28.12%、18.14%的变量(图 4)。从图 4中可以看出土壤TK与细菌群落的相关性最大,土壤SM、EC、TN、TP与细菌群落的相关系次之,土壤PH、OM与细菌群落的相关性最小。其中,2个生长阶段根际土壤的细菌群落与土壤全氮、含水率之间呈正相关关系,与土壤全钾呈负相关关系;此外,营养生长期根际土壤细菌群落与土壤有机质呈正相关关系,与土壤全磷、pH和电导率呈负相关关系,而生殖生长期根际土壤细菌群落与土壤有机质呈负相关关系,与全磷、pH和电导率呈正相关关系。

|

| 图 4 土壤细菌群落与土壤性质的RDA分析 Figure 4 RDA analysis of soil bactreial community and soil properties 注:图中不同形状和颜色的符号表示不同样地和不同生长阶段各样本组的细菌群落;箭头表示环境因子,箭头连线的长度带表某个环境因子与群落分布间相关程度的大小,箭头越长,说明相关性越大,反之越小;细菌群落与环境因子之间的夹角代表细菌群落与环境因子之间正负相关关系,锐角表示正相关,钝角表示负相关,直角表示不相关. Note: The symbol of different shapes and colors in this diagram is indicating the bacterial communities of each sample groups in different plots and growth stages; Arrows represent environment factors, the length of the arrowhead line represent the degree of correlation between an environmental factor and community distribution, the longer the arrow shows the greater the correlation is, and vice versa; The angle between the bacterial community and the environmental factor represents the positive and negative correlation between it, acute angle is positive correlation, obtuse is negative correlation and right angles are not related. |

|

|

本研究使用高通量测序对裕民县道地药材红花的4组36个土壤样品进行细菌16S rRNA基因测序,以97%相似度划分,共得到10 303个OTU,表明道地药材红花根际微环境中存在着丰富的微生物,这些微生物不仅数量众多,而且种类也很丰富。本研究的4组土壤样品中的优势菌门是放线菌门(32.9%)和变形菌门(28.7%),相对丰度较高的菌门有厚壁菌门(9.0%)、酸杆菌门(8.0%)和芽单胞菌门(6.2%) (图 1)。放线菌是药用植物根际环境中一类重要的微生物,在促进植物生长方面发挥重要作用,而且可以调节植物与病原菌以及微环境的生物平衡,从而达到防治病害的作用[7-8]。张盼盼等的研究发现南方红豆杉的根际土壤放线菌中有30.9%的菌株具有抑制植物病原真菌活性,并且其中6株放线菌对多种植物病原真菌显示了强的抑菌活性[9]。此外,通过对近年来药用植物根际微生物类群的研究发现,变形菌门和厚壁菌门为主要类群,有助于药用植物产量及质量的提高[10-14],本研究中变形菌门和厚壁菌门的相对丰度分别为28.7%、9.0%,在红花根际细菌群落中占较大比重,与前人的研究结果基本一致。

巨大数量的土壤微生物类群还体现出了土壤微生物群落结构的复杂性,本研究中所检测到的属水平的优势菌属在两个生长阶段乃至不同样地之间差异较大(图 2),这可能与不同样地土壤性质存在差异有关(表 1)。3块红花样地营养生长期根际土壤的优势菌属分别如下,V1R优势菌属有鞘氨醇单胞菌属(Sphingomonas)、乳酸菌属(Lactobacillus)、布鲁氏菌属(Brucella)、叶杆菌属(Phyllobacterium)、根瘤菌属(Rhizobium)、Bosea、慢生根瘤菌属(Bradyrhizobium)、藤黄色杆菌属(Luteibacter)、气单胞菌属(Aeromonas),V2R优势菌属有芽孢杆菌属(Bacillus)、Bryobacter,V3R中芽单胞菌属(Gemmatimonas)是优势菌属;生殖生长期各样地根际土壤优势菌属分别如下,R1R优势菌属是Candidatus_Nitrososphaera、Gaiella,R2R优势菌属是Candidatus_Nitrososphaera、寡养单胞菌属(Stenotrophomonas),R3R中链霉菌属(Streptomyces)、芽单胞菌属(Gemmatimonas)和Haliangium是优势菌属。根际土壤中细菌优势菌属分布表现出如此大的差异,说明道地药材红花的根际细菌群落结构较为复杂,物种多样性较高。根际微生物可以直接作用于植物,促进或抑制其生长,导致药用植物产量和质量的变化,根际微生物的多样性在促进植物生长和健康方面发挥着关键作用[15]。有研究表明鞘氨醇单胞菌属对环境污染物具有较强的降解能力[16],能够促进植物吸收与生长[17];链霉菌属细菌在可以诱导寄主植物产生防御反应,使得局部或系统获得抗性[18];芽孢杆菌属细菌可以耐受各种不良的环境条件,部分细菌对病原菌有一定的拮抗作用[19-21],而这些细菌对道地药材红花的生长乃至红花的药材品质有怎样的影响有待进一步研究。

3.2 影响红花根际细菌群落的因素物种多样性代表着物种演化的空间范围和对特定环境的生态适应性,在本研究中,红花根际土壤的pH、电导率、含水率及全磷含量在两个生长时期之间差异显著(表 1),而红花土壤细菌的丰富度指数Chao1和多样性指数Shannon在两个生长阶段之间无显著性差异(表 2),根据Loreau等[22]的假设来分析,红花根际的细菌在两个生长阶段均表现出较高的多样性却无显著性差异存在,是由于红花根际微生态环境中有许多适应环境变化的细菌存在,如鞘氨醇单胞菌属[17]、芽孢杆菌属[20-22]等,使得红花根际微生态系统保持稳定,并由此推测这种适应能力强的细菌可能对红花道地性的形成有积极作用。

本研究中红花不同生长阶段的优势菌属的分布差异明显(图 2),有研究表明土壤微生物群落受生境内环境因素的影响,如pH[23-24]、土壤水分含量[25]、土壤养分含量及含盐量[26]等的影响,甚至有研究者指出细菌群落的分布和结构在很大程度上可以仅凭生境特性来解释[24]。本研究使用RDA分析探讨细菌群落与环境因子之间的关系,结果显示土壤性质对微生物群落的解释量仅占46.26% (图 4),表明红花土壤细菌群落的形成除了与土壤性质有关外,还受其他因素的影响。有研究指出,植物根际微生物群落与植物生长阶段和根系分泌物密切相关[27-29]。

同种药用植物在不同的生长阶段,其根际微生物也存在一定的差异。本研究中,红花不同生长阶段的优势菌属差异明显,原因可能是红花根际在营养生长期生理代谢旺盛,其代谢产物仅有利于某些特定菌群的生长而发展成为优势菌群,这些优势菌群对另外一些菌群具有竞争优势,结果造成少数优势菌群的大量繁殖,另外一些菌群在竞争中被抑制或消失,且有研究结果证实细菌丰度受植物生长阶段的显著影响[27]。

除此之外,根系分泌物是植物与其根际微生物相互作用的中间媒介,且植物根系活动的分泌物和脱落物是根际微生物主要的营养源和能源,因此根系分泌物与细菌类群密切相关[28-29]。本研究虽然没有测量道地药材红花的根系分泌物,但据前人的研究报道根系分泌物受作物生长阶段的强烈影响,这种关系反过来又影响细菌群落的演替[30-32]。道地药材红花营养生长期的植株生长代谢逐渐增强,根际分泌物也逐渐增多,从而有利于一些细菌的生长和繁殖;生殖生长期细菌数量呈下降趋势,所以这种变化可能与红花根际生长代谢下降导致根际分泌物减少紧密相关。

由此可见,土壤性质、植物生长阶段和根系分泌物是影响红花根际细菌群落的主要因素,这些因素可能通过影响根际细菌群落作用于红花道地性的形成。

4 结论经分析,红花根际土壤中存在大量适应环境变化的细菌,这些细菌的存在可能对红花道地性的形成有积极作用。此外,土壤性质、植物的生长阶段和根系分泌物可能通过影响红花根际细菌群落来致力于红花道地性的形成。

| [1] |

Liang HZ, Dong W, Yu YL, et al. Advances in studies on safflower (Carthamus tinctorius L.) at home and abroad[[J]. studies on safflower (Carthamus tinctorius L.) at home and abroad[J]., 2015, 43(16): 71-74. (in Chinese) 梁慧珍, 董薇, 余永亮, 等. 国内外红花种质资源研究进展[J]. 安徽农业科学, 2015, 43(16): 71-74. |

| [2] |

Jiang S, Duan JA, Qian DW, et al. Effects of microbes in plant rhizosphere on geoherbalism[J]. Soil, 2009, 41(3): 344-349. (in Chinese) 江曙, 段金廒, 钱大玮, 等. 根际微生物对药材道地性的影响[J]. 土壤, 2009, 41(3): 344-349. DOI:10.3321/j.issn:0253-9829.2009.03.003 |

| [3] |

Wu LY, Wen CQ, Qin YJ, et al. Phasing amplicon sequencing on Illumina MiSeq for robust environmental microbial community analysis[J]. BMC Microbiology, 2015, 15: 125. DOI:10.1186/s12866-015-0450-4 |

| [4] |

You J, Wu G, Ren FP, et al. Microbial community dynamics in Baolige oilfield during MEOR treatment, revealed by Illumina MiSeq sequencing[J]. Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology, 2016, 100(3): 1469-1478. DOI:10.1007/s00253-015-7073-4 |

| [5] |

Lin XG. Principles and Methods of Soil Microbial Research[M]. Beijing: Higher Education Press, 2010. (in Chinese) 林先贵. 土壤微生物研究原理与方法[M]. 北京: 高等教育出版社, 2010. |

| [6] |

Bao SD. Soil Agricultural Chemistry Analysis[M]. Beijing: China Agriculture Press, 2000: 1-114. (in Chinese) 鲍士旦. 土壤农化分析[M]. 北京: 中国农业出版社, 2000: 1-114. |

| [7] |

Doumbou CL, Salove MKH, Crawford DL, et al. Actinomycetes, promising tools to control plant diseases and to promote plant growth[J]. Phytoprotection, 2001, 82(3): 85-144. DOI:10.7202/706219ar |

| [8] |

Tokala RK, Strap JL, Jung CM, et al. Novel plant-microbe rhizosphere interaction involving Streptomyces lydicus WYEC108 and the pea plant (Pisum sativum)[J]. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 2002, 68(5): 2161-2171. DOI:10.1128/AEM.68.5.2161-2171.2002 |

| [9] |

Zhang PP, Qin S, Yuan B, et al. Diversity and bioactivity of actinomycetes isolated from medicinal plant Taxus chinensis and rhizospheric soil[J]. Acta Microbiologica Sinica, 2016, 56(2): 241-254. (in Chinese) 张盼盼, 秦盛, 袁博, 等. 南方红豆杉内生及根际放线菌多样性及其生物活性[J]. 微生物学报, 2016, 56(2): 241-254. |

| [10] |

Ying YX, Ding WL, Li Y. Characterization of soil bacterial communities in rhizospheric and nonrhizospheric soil of Panax ginseng[J]. Biochemical Genetics, 2012, 50(11/12): 848-859. |

| [11] |

Kumar G, Kanaujia N, Bafana A. Functional and phylogenetic diversity of root-associated bacteria of Ajuga bracteosa in Kangra valley[J]. Microbiological Research, 2012, 167(4): 220-225. DOI:10.1016/j.micres.2011.09.001 |

| [12] |

Bafana A. Diversity and metabolic potential of culturable root-associated bacteria from Origanum vulgare in sub-Himalayan region[J]. World Journal of Microbiology and Biotechnology, 2013, 29(1): 63-74. DOI:10.1007/s11274-012-1158-3 |

| [13] |

Shang QH, Yang G, Wang Y, et al. Illumina-based analysis of the rhizosphere microbial communities associated with healthy and wilted Lanzhou lily (Lilium davidii var. unicolor) plants grown in the field[J]. World Journal of Microbiology and Biotechnology, 2016, 32(6): 95. DOI:10.1007/s11274-016-2051-2 |

| [14] |

Jin H, Yang XY, Yan ZQ, et al. Characterization of rhizosphere and endophytic bacterial communities from leaves, stems and roots of medicinal Stellera chamaejasme L[J]. Systematic and Applied Microbiology, 2014, 37(5): 376-385. DOI:10.1016/j.syapm.2014.05.001 |

| [15] |

Mendes R, Kruijt M, de Bruijn I, et al. Deciphering the rhizosphere microbiome for disease-suppressive bacteria[J]. Science, 2011, 332(6033): 1097-1100. DOI:10.1126/science.1203980 |

| [16] |

Bending GD, Lincoln SD, Srensen SR, et al. In-field spatial variability in the degradation of the phenyl-urea herbicide isoproturon is the result of interactions between degradative Sphingomonas spp. and soil pH[J]. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 2003, 69(2): 827-834. DOI:10.1128/AEM.69.2.827-834.2003 |

| [17] |

Takeuchi M, Sakane T, Yanagi M, et al. Taxonomic study of bacteria isolated from plants: proposal of Sphingomonas rosa sp. nov., Sphingomonas pruni sp. nov., Sphingomonas asaccharolytica sp. nov., and Sphingomonas mali sp. nov[J]. International Journal of Systematic Bacteriology, 1995, 45(2): 334-341. DOI:10.1099/00207713-45-2-334 |

| [18] |

Yi L, Zhang Y, Liao XL, et al. Advances in the study of plant diseases by Streptomyces[J]. Jiangsu Agricultural Sciences, 2014, 42(3): 91-95. (in Chinese) 易龙, 张亚, 廖晓兰, 等. 链霉菌防治植物病害的研究进展[J]. 江苏农业科学, 2014, 42(3): 91-95. |

| [19] |

Xing JS, Li R, Zhao L, et al. Studies on identification of one high protease producing bacteria for biocontrol and the antaganism against plant pathogens[J]. Acta Agriculturae Boreali-Occidentalis Sinica, 2008, 17(1): 106-109. (in Chinese) 邢介帅, 李然, 赵蕾, 等. 产蛋白酶生防细菌的筛选及其对病原真菌的拮抗作用[J]. 西北农业学报, 2008, 17(1): 106-109. DOI:10.3969/j.issn.1004-1389.2008.01.025 |

| [20] |

Yao LJ, Wang Q, Fu XC, et al. Isolation and Identification of endophytic bacteria antagonistic to wheat sharp eyespot disease[J]. Chinese Journal of Biological Control, 2008, 24(1): 53-57. (in Chinese) 姚丽瑾, 王琦, 付学池, 等. 小麦纹枯病生防芽孢杆菌的筛选及鉴定[J]. 中国生物防治, 2008, 24(1): 53-57. DOI:10.3321/j.issn:1005-9261.2008.01.010 |

| [21] |

Chen D, Yin XM, Zhang RY. Preliminary study on the inhibition of Bacillus subtilis B215 on banana anthracnose[J]. Guangxi Tropical Agriculture, 2008(1): 1-3. (in Chinese) 陈弟, 殷晓敏, 张荣意. 内生枯草芽孢杆菌B215对香蕉炭疽菌抑制作用初探[J]. 广西热带农业, 2008(1): 1-3. DOI:10.3969/j.issn.2095-0764.2008.01.001 |

| [22] |

Loreau M, Downing AL, Emmerson MC, et al. A new look at the relationship between diversity and stability[A]//Loreau M, Naeem S, Inchausti P. Biodiversity and Ecosystem Functioning[M]. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2002: 79-91

|

| [23] |

Fierer N, Jackson RB. The diversity and biogeography of soil bacterial communities[J]. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 2006, 103(3): 626-631. DOI:10.1073/pnas.0507535103 |

| [24] |

Lauber CL, Hamady M, Knight R, et al. Pyrosequencing-based assessment of soil pH as a predictor of soil bacterial community structure at the continental scale[J]. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 2009, 75(15): 5111-5120. DOI:10.1128/AEM.00335-09 |

| [25] |

Bachar A, Soares MIM, Gillor O. The effect of resource islands on abundance and diversity of bacteria in arid soils[J]. Microbial Ecology, 2012, 63(3): 694-700. DOI:10.1007/s00248-011-9957-x |

| [26] |

Leaungvutiviroj C, Piriyaprin S, Limtong P, et al. Relationships between soil microorganisms and nutrient contents of Vetiveria zizanioides (L.) Nash and Vetiveria nemoralis (A.) Camus in some problem soils from Thailand[J]. Applied Soil Ecology, 2010, 46(1): 95-102. DOI:10.1016/j.apsoil.2010.06.007 |

| [27] |

Wang JC, Xue C, Song Y, et al. Wheat and rice growth stages and fertilization regimes alter soil bacterial community structure, but not diversity[J]. Frontiers in Microbiology, 2016, 7: 1207. |

| [28] |

Dunfield KE, Germida JJ. Diversity of bacterial communities in the rhizosphere and root interior of field-grown genetically modified Brassica napus[J]. FEMS Microbiology Ecology, 2001, 38(1): 1-9. |

| [29] |

Nardi S, Concheri G, Pizzeghello D, et al. Soil organic matter mobilization by root exudates[J]. Chemosphere, 2000, 41(5): 653-658. DOI:10.1016/S0045-6535(99)00488-9 |

| [30] |

Yang CH, Crowley DE. Rhizosphere microbial community structure in relation to root location and plant iron nutritional status[J]. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 2000, 66(1): 345-351. DOI:10.1128/AEM.66.1.345-351.2000 |

| [31] |

Duineveld BM, Kowalchuk GA, Keijzer A, et al. Analysis of bacterial communities in the rhizosphere of chrysanthemum via denaturing gradient gel electrophoresis of PCR-amplified 16S rRNA as well as DNA fragments coding for 16S rRNA[J]. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 2001, 67(1): 172-178. DOI:10.1128/AEM.67.1.172-178.2001 |

| [32] |

Xu YX, Wang GH, Jin J, et al. Bacterial communities in soybean rhizosphere in response to soil type, soybean genotype, and their growth stage[J]. Soil Biology and Biochemistry, 2009, 41(5): 919-925. DOI:10.1016/j.soilbio.2008.10.027 |

2018, Vol. 45

2018, Vol. 45