扩展功能

文章信息

- 苏志国, 张衍, 代天娇, 陈嘉瑜, 张永明, 温东辉

- SU Zhi-Guo, ZHANG Yan, DAI Tian-Jiao, CHEN Jia-Yu, ZHANG Yong-Ming ZHANG Yong-Ming, WEN Dong-Hui WEN Dong-Hui

- 环境中抗生素抗性基因与Ⅰ型整合子的研究进展

- Antibiotic resistance genes and class 1 integron in the environment: research progress

- 微生物学通报, 2018, 45(10): 2217-2233

- Microbiology China, 2018, 45(10): 2217-2233

- DOI: 10.13344/j.microbiol.china.180042

-

文章历史

- 收稿日期: 2018-01-12

- 接受日期: 2018-03-26

- 网络首发日期(www.cnki.net): 2018-05-29

2. 江南大学环境与土木工程学院 江苏 无锡 214122;

3. 上海师范大学生命与环境科学学院 上海 200234

2. School of Environment and Civil Engineering, Jiangnan University, Wuxi, Jiangsu 214122, China;

3. College of Life and Environmental Sciences, Shanghai Normal University, Shanghai 200234, China

抗生素(Antibiotics)在医药、畜牧和水产养殖业的大量使用造成了环境中抗性耐药菌(Antibiotic resistant bacteria,ARB)和抗性基因(Antibiotic resistance genes,ARGs)日益增加,ARGs作为一种新型环境污染物引起人们的广泛关注[1]。在外界环境的选择压力下,细菌除了通过自身突变获得耐药性之外,基因的水平转移(Horizontal gene transfer,HGT)作为微生物间主要的遗传物质交换方式[2-3],是细菌获得ARGs的主要途径。同时,这也造成了ARGs在环境中的持久性残留,以及在不同环境介质中的传播、扩散,对生态环境和人体健康产生了极大的潜在风险[4]。近年来研究发现了一种携带有多种ARGs的新型重组表达系统——整合子(Integron)[5],它能促进ARGs更广泛的传播,并且结构复杂的Ⅰ型整合子(全文简写为Int I)与ARGs关系更为密切,能够通过位点特异性重组将不同ARGs进行重排,进而通过接合型质粒传播,对ARGs在环境中的传播扩散起到了至关重要的作用。目前Ⅰ型整合子日益成为研究的热点[6-7]。

本文介绍环境中ARGs和Int I的来源与分布,阐述Int I特殊的结构和功能,以及Int I在ARGs传播、扩散过程中的作用。同时,梳理目前该领域的一些研究方法,以期为阐释ARGs传播的机理和管控ARGs传播的环境风险提供科学参考。

1 抗生素抗性基因的研究现状 1.1 环境中抗生素及其抗性基因的来源与传播抗生素作为20世纪最重要的医学发现之一,至今已拯救了无数生命,为人类感染性疾病的防治做出了重要贡献[8]。自1943年青霉素应用于临床以来,被发现的抗生素种类总数已超过9 000种[9],临床上常用的也有几百种[10]。按照抗生素的化学结构主要可分为β-内酰胺类、磺胺类、喹诺酮类、大环内酯类、四环素类、氨基糖苷类和多肽类等[11]。目前抗生素在全球范围内大量应用于人类疾病治疗和集约化畜禽养殖业,由于兽用抗生素具有防治动物疫病和促进生长的双重功效,使用和消耗量远远高于医用抗生素[12]。据统计,美国2011年和2012年的抗生素使用量大约是每年1.79万t,用于动物的比例高达81.6%;而我国更是抗生素的生产和使用大国,2013年抗生素的使用总量达到16.2万t,其中52%用于养殖业,最后释放到河流和水渠中的抗生素就有5.38万t[13]。这表明抗生素的使用情况已经非常广泛,尤其是在畜牧养殖行业滥用问题更为严重。

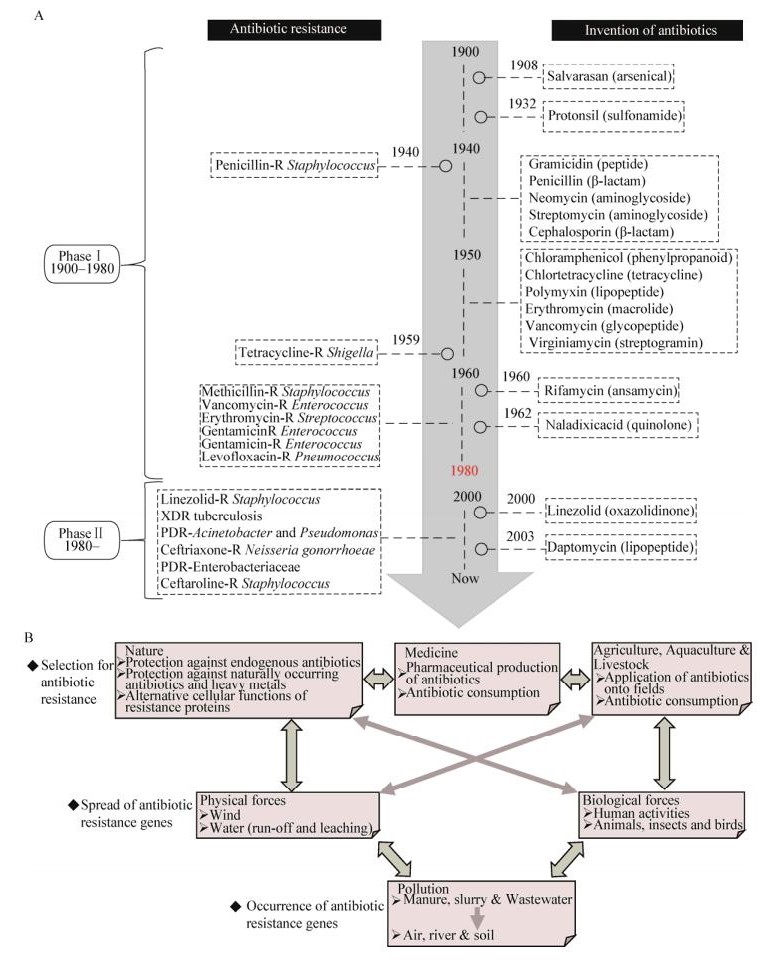

自然界微生物会通过使抗生素失活、细胞外排泵、药物靶位点修饰等机制对抗生素产生固有的耐药性[14],这是存在于环境微生物基因组上的抗性基因所表现出的内在抗性(Intrinsic resistance)[15]。这种抗性的产生实际上是微生物的一种自然进化过程,目的是帮助微生物更好地适应环境,这已经通过某些抗性基因的进化分析被证实[16-17]。但是,抗生素的长期大规模滥用加速了这个过程,极大地增加了耐药性的发生频率[4, 18],抗性微生物在数量、多样性以及抗性强度上都表现出了显著增大的发展趋势(图 1A)。根据美国疾病控制与预防中心(Centers for disease control and prevention,CDC)关于美国1900-1996年间感染死亡率的统计数据[19],可以将抗生素及其抗性发展分为两个阶段。前期由于抗生素的发现和使用,而产生抗性的菌株又比较少,使得因感染死亡的人数急剧下降,在此期间有研究对分离的433株肠杆菌进行抗性检测,只有不到3%的菌株对抗生素具有抗性[20];而后期自20世纪80年代以来,越来越多的菌株对主要临床用抗生素产生耐药性,并且由单一耐药性发展到多重耐药性,导致感染死亡率有一个明显的升高趋势[21]。

|

| 图 1 环境中抗生素及其抗性基因的来源、分布与传播 Figure 1 The sources, distribution and dissemination of antibiotics and antibiotic resistance genes (ARGs) in the environment 注:A:抗生素及其抗性基因的发展历程(数据来自https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/);B:环境中抗生素抗性基因的来源与传播途径[39]. Note: A: The development course of antibiotics and ARGs (data from https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/); B: The sources and dissemination route of ARGs in the environment[39]. |

|

|

环境中抗生素及其抗性基因来源与分布广泛,可以通过多种直接或间接的传播途径扩散并最终进入各类环境中(图 1B)。当然,自然环境介质中微生物会产生抗生素和内在抗性,但这种浓度在环境中非常低,而目前环境抗生素及抗性基因残留主要是外源输入[22]。主要的污染源包括抗生素生产企业废水、医院废水、畜牧业、水产养殖、人畜粪便和城市污水处理厂污水[23]。同时,ARGs主要是以水、土壤、空气等介质作为储库和传播扩散的媒介,并且会通过食物链直接进入人体[24],对人类健康造成潜在的危害。因此,Pruden等[25]在2006年便提出将ARGs视为一种新型的环境污染物,对其来源、分布和传播的研究也越来越受到人们的重视。

ARGs对水环境的污染更严重,比如养殖场化粪池系统内的ARB及ARGs可以通过渗透、泄漏等方式进入地表水和地下水[26],进而对水质产生影响。水产养殖则是ARGs进入水环境最直接的途径,这与抗生素大量投入水体和含有ARGs饲料的直接投喂有关[27]。由于现有的水处理技术对许多抗生素类物质没有明显的去除效果,尤其是对污水处理厂中高浓度的四环素抗性基因,生物处理和紫外消毒都无法有效去除[28],因此污水处理系统是ARGs的重要储存库[29]。Su等[30]对中国17个主要城市32个污水处理厂的进水进行了ARGs的研究,通过高通量测序和宏基因组分析,揭示了污水处理厂中ARGs丰度的季节性变化和地理分布差异,证明了人类肠道微生物对ARGs扩散的潜在贡献。张衍等[31-32]则跟踪了ARGs在污水处理工艺流程中的变化,结果发现不同的处理工艺对细胞态和游离态ARGs有不同的去除率,污水处理厂出水中游离态ARGs的比例更高,将生物处理出水和消毒处理出水静置一定时间,其中游离态ARGs丰度都有不同程度的提高,这表明污水处理厂排放的游离态ARGs在受纳环境中的传播扩散会产生更大的生态风险。同时,Su等[30]根据人均每天ARGs承载量(9.47×1013 copies/d)计算了中国省级行政区域内城市ARGs承载量,结果显示中国各省ARGs承载量以“胡焕庸线”为分界,表现出与人口密度较为一致的分布,莫兰指数的计算结果也表明了显著的空间自相关性,这暗示着人口的不断增长和经济的快速发展加剧了ARGs的排放与分布,已经使中国面临着巨大压力。

而对于ARGs的最大受纳者——自然水环境来说,大量研究都证实人类活动对ARGs在水环境中的丰度和传播起到了主导作用,尤其是对河流[33]、海湾[34]、湖泊[35]等水体或沉积物影响严重。比如Zhu等[34]对中国沿海环境的研究表明,ARGs在河口沉积物中的丰度和多样性很高,一共检测到了超过200种不同的ARGs,细菌群落、抗生素残留和社会经济因素都会影响ARGs的分布。当然,ARGs在土壤、空气等环境介质中的传播扩散也不容忽视,其中粪便施肥是土壤ARGs散播的主要途径[36],而大气环境ARGs的相关研究则主要集中在对养殖场、医院病房[37-38]等空气环境中ARB及ARGs的分析,目前有关ARGs在土壤和大气环境中迁移转化规律的研究还不系统。

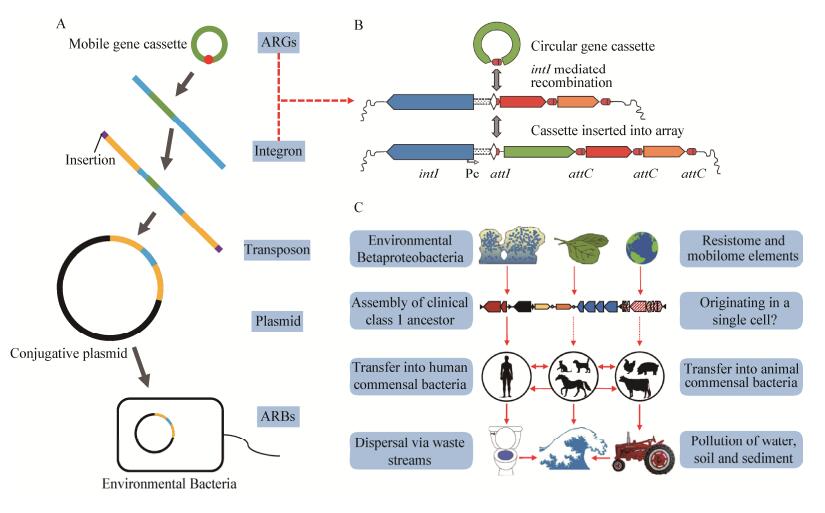

1.2 抗生素抗性基因的水平转移与潜在风险环境中残留的抗生素会刺激环境微生物,从而引起其体内ARGs的产生和选择,这是微生物自然的适应过程[39],这一过程ARGs的产生较为缓慢,但携带ARGs具有抗性的微生物会获得竞争优势,并不断将其ARGs传播给其他微生物。众多的研究证实ARGs具有较高的移动性,主要是通过HGT机制大大增加了ARGs在不同微生物间传播扩散的频率[4, 40]。ARGs发生水平转移的分子机制主要有接合(Conjugation)、转化(Transformation)和转导(Transduction) 3种。接合转移的载体主要是可自主转移的质粒(Self-transmissible plasmid)和接合性转座子(Conjugative transposon);转化过程是胞外游离ARGs被处于感受态的受体菌摄入体内,并在受体菌内整合表达,使其获得抗性的过程;转导则是借助于噬菌体将ARGs由供体菌转移给受体菌的过程[41]。整合子作为基因捕获系统,可以携带重组的基因盒插入到转座子或质粒中,在不同的细菌中运动,对环境中ARGs水平转移过程发挥重要作用(图 2A)。在开放的自然环境中进行的ARGs水平转移过程会受到更为复杂的因素影响,比如环境残留的抗生素浓度与ARGs的广泛传播有直接关系[8],环境温度、pH及Ca2+或Mg2+浓度是否适宜也是ARGs能够发生水平转移的必要条件[41]。另外,很多研究者发现环境中重金属、消毒剂、洗涤剂等外源污染物对ARGs的筛选和水平转移都有不同程度的促进作用[42]。近年来,在各类生态系统中检测到胞外DNA分子和能主动摄取外源DNA的感受态细胞[43],甚至还检测到胞外游离的ARGs[31-32],使人们对环境中发生的水平基因转移有了新的认识。

|

| 图 2 环境中Ⅰ型整合子的结构、功能、来源和传播 Figure 2 The structure, function, sources and dissemination of class 1 integron in the environment 注:A:抗生素抗性基因基于可移动遗传元件的传播机制;B:Ⅰ型整合子的结构和功能[67];C:Ⅰ型整合子的来源和传播途径[71]. Note: A: The dissemination mechanism of ARGs based on mobile elements; B: Class 1 integron structure and function[67]; C: The sources and dissemination route of class 1 integron[71]. |

|

|

环境中拥有基因水平转移等内在机制的微生物组成了一个巨大的ARGs储存库[16],并可能将抗生素耐药性转移到人类共生微生物和病原体中[44-45],对生态环境和人类健康造成了较大的潜在风险。研究表明,目前许多肉类和蔬菜食品中都检测到了不同抗生素的耐药菌株[46],在饮用水中也检测到了ARGs的广泛存在[47]。ARGs随粪便农业肥料进入土壤生态系统,从而会转移到农作物中,通过植物性食物链给人类健康带来危害;而由于水生生态系统十分普遍的ARGs污染情况,水生生物体内也相继检测出抗性基因,人类会食用鱼类等高营养级生物,ARGs就通过动物性食物链进行传递[43, 48-49]。当然最直接的危害是环境致病菌耐药性的增加和扩散,近年来耐甲氧西林金黄色葡萄球菌(Methicillin- resistant Staphylococcus aureus,MRSA)、泛耐药鲍氏不动杆菌(Pandrug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii,PRAB)、碳青霉烯类耐药铜绿假单胞菌(Carbapenem-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa,CRPA)、碳青霉烯类耐药肠杆菌(Carbapenem- resistant Enterobacteriaceae, CRE)等典型多重耐药性细菌的出现[41, 50],对人类疾病的医治带来极大的困难。世界卫生组织调查表明[43],在全球因呼吸道疾病、感染性腹泻、麻疹、艾滋病、结核病感染造成的死亡病例中,引起这些疾病的致病菌对常用药物的耐药性几乎是100%。同时,目前发现的新型耐药性基因NDM-1和MCR-1等会通过水平基因转移在多种菌株间快速传播,携带有该类基因的细菌几乎能够抵抗所有抗生素,更使公共卫生安全面临巨大挑战[51-52]。

1.3 抗生素抗性基因的去除方法与技术对于自然环境中残留的ARGs来说,光照、温度、氧含量以及微生物群落组成都可能影响其降解过程[53]。比如光照和厌氧环境都会加速ARGs降解,温度则是影响磺胺类和大环内酯类抗性基因变化的重要因素,细菌类型和多样性的变化也会促使ARGs含量发生变化。上述因素均显著影响人工处理系统中不同处理工艺对ARGs的去除效果。目前ARGs的去除方法主要有物理法、化学法和生物法。

物理法的去除机理主要有吸附和光降解等作用,包括沉淀、过滤和紫外消毒技术等。比如城市污水处理厂初沉池可明显去除污水中tetA和tetB四环素类抗性基因[54],Guo等[55]利用UV辐射对城市污水进行消毒处理,结果发现,在5 mJ/cm的UV剂量时,红霉素类抗性基因和四环素类抗性基因分别降低了3.0±0.1 log和1.9±0.1 log,而UV剂量增加到10 mJ/cm时,红霉素类抗性基因浓度更是下降到仪器检出限外。

化学法主要包括加氯消毒技术和Fenton氧化、臭氧氧化、光催化氧化等高级氧化技术。许多研究表明加氯消毒对ARGs的去除效果不佳,更重要的是其可能会增加ARGs在废水中转移传播的风险[56],相比之下高剂量(> 10 mJ/cm)的UV消毒能直

接损坏携带有ARGs的质粒,从而极大程度地抑制HGT[57]。高级氧化技术是依赖反应生成的具有强氧化能力的羟基自由基(·OH)将ARGs进行氧化处理,其中Zhang等[58]比较了Fe2+/H2O2和UV/H2O2对废水中ARGs (sul1、tetX、tetG)的去除效果,发现Fe2+/H2O2处理效果略优于UV/H2O2,同时综合考虑初始反应物质摩尔比、H2O2浓度、pH、反应时间等影响因素,Fe2+/H2O2处理效率最佳时能使ARGs浓度减少2.58-3.79 log。Guo等[59]研究了TiO2薄膜光催化技术对水中ARB和ARGs (mecA、ampC)的去除作用,结果表明TiO2薄膜在UV254辐射下能非常有效地去除ARB,同时可以分别去除5.8 log的mecA和4.7 log的ampC。Moreira等[60]将臭氧氧化技术与光催化结合,研究其对城市污水、地表水中ARGs的去除作用,结果发现光催化臭氧氧化能有效去除ARGs,基本上ARGs浓度减少到仪器检出限附近(10 copies/mL),还有研究表明臭氧氧化和光催化氧化之间的协同效应会促进对ARGs的去除[61]。

生物法包括传统的生物处理工艺和人工湿地技术等,胞内ARGs随细胞而被截留、沉降,从而降低了出水ARGs含量。例如对于磺胺类和四环素类抗性基因来说,MBR工艺的去除效果好于活性污泥法,ARGs浓度可以减少2.57-7.06 log[53]。Chen等[62]研究了曝气生物滤池、人工湿地、UV消毒等3种工艺对ARGs (tetM、tetO、tetQ、tetW、sul1、sul2、intI1)的去除效果,结果显示人工湿地技术最为有效,能将ARGs浓度减少1-3 log。又有研究[63]考察了人工湿地3种模式(地表径流、水平潜流、垂直潜流)和2种植物(水竹芋、鸢尾)的设计对去除生活污水中ARGs的影响,发现对ARGs的去除率均在63.9%-84.0%,垂直潜流式并种植水竹芋的人工湿地对ARGs的去除效果最好。利用垂直潜流式人工湿地对养殖废水中磺胺类[64]和四环素类抗性基因[65]的去除率也分别在80%和90%以上。目前随着纳米技术应用于水处理领域,一些研究发现纳米颗粒可能会促进多重耐药基因的水平转移,但具体对ARGs去除或传播有何影响及其机制还有待探索[56]。

上述方法均有各自的适用条件和优缺点,探索高效去除ARGs的方法及优化已有处理工艺依然是今后继续研究的方向,这对有效遏制ARGs在环境中的传播扩散具有重要意义。另一方面,要从源头加强环境管理,相关行业出台有关抗生素的排放标准,以减少抗生素向外环境的排放,对环境中大量残留的抗生素也要应用多种技术进行降解处理,进而消除其对ARGs的诱导筛选及传播的促进作用,达到双管齐下的目的[41]。与此同时,减少ARGs污染的另一个思路是深入研究ARGs的水平转移机制,并有针对性地进行过程控制,这也对将来的精准调控提出了新挑战。

2 Ⅰ型整合子的研究现状 2.1 Ⅰ型整合子的结构与功能整合子(Integron)的概念在1989年由Stokes等首次提出[5],它是一种可移动的DNA分子,具有特殊结构,可捕获和整合外源性基因,特别是抗生素抗性基因、重金属抗性基因等,使之转变为功能性基因的表达单位,之后可通过转座子和质粒在细菌中水平传播(图 2 A)。

根据intI基因编码的不同整合酶可以对整合子进行分类,现已发现至少5种类型的整合子(Ⅰ、Ⅱ、Ⅲ、Ⅳ、Ⅴ型整合子)能够使ARGs实现水平转移[66],目前对整合子-基因盒耐药机制的研究主要以Ⅰ型整合子为主。Ⅰ型整合子(Int I)主要有3个核心结构:编码整合酶的基因intI、整合子重组位点attI和整合子可变区启动子Pc[67]。这些特征可以捕捉和表达外源基因作为基因盒的一部分,利用intI编码的整合酶活性将基因盒整合到attI重组位点[68],随后从Pc开始表达外源基因[69](图 2B)。这里的基因盒也是一种可移动性元件,由结构基因和一个整合位点attC组成,虽然其能以环状形式独立存在,但是绝大多数基因盒都不含有启动子,所以只有在整合子中才能被转录表达[70]。正是因为有这样的结构,Int I可以水平转移到广泛的共生和致病性细菌中,一旦人们试图使用抗生素控制这些细菌,就会造成多种ARGs的累积,目前发现Int I携带的ARGs基因盒有130多种[71]。对于临床Int I的起源来说,最好的解释是来自环境中变形菌的染色体Int I被Tn402家族的转座子捕获,该整合子携带了一个编码消毒剂抗性的基因盒(qacE),随后捕获了一个磺胺类抗性基因(sul1),删除了qacE基因盒的末端[72-73]。而整合子中基因盒的来源则比较广泛,推测其由mRNA通过逆转录而来或者来自超级整合子,环境微生物是基因盒庞大的储备库[74]。

Ⅰ型整合子的作用机制主要体现在其介导的ARGs水平传播和转移[75],一方面是整合子对环境中游离的环状基因盒进行捕获和剪切,主要是通过整合酶的催化在attC和attI之间发生特异性整合,一个整合子可以捕获一个或多个基因盒;另一方面是整合子携带着重组的基因盒插入到转座子或接合质粒中,在质粒、转座子、染色体间移动,实现基因的水平传播和转移。在过去几十年的研究中,发现自然环境中整合子不仅是耐药细菌特有的结构,而且在细菌基因组进化[73],特别是对人类活动造成的环境压力适应性方面[6]具有重要作用。

2.2 Ⅰ型整合子在环境中的来源与分布整合子作为多样、古老的遗传元件,在非常广泛的环境中被发现。在超过15%的环境微生物基因组序列中都发现了多种整合子的整合酶基因[72],这其中Int I在临床耐药性研究中发挥了重要作用。大量研究表明Int I在多种临床耐药菌中广泛存在,并且这些携带整合子的耐药菌主要是革兰氏阴性菌[75],如临床研究较多的大肠埃希菌[76]、铜绿假单胞菌[77-78]、嗜水气单胞菌[79]、阴沟肠杆菌、鲍曼不动杆菌、克雷伯菌属、埃希菌属、沙雷菌属、肠杆菌属、假单胞菌属、变形菌等。因此Int I的来源与ARGs一致,主要是来自医疗废水、畜禽养殖废物及工农业生产废水等污染源,通过食物和水在人或动物的共生细菌之间进行传递,随后扩散到水、土壤、沉积物等环境介质中,对自然环境造成了潜在的危害[71](图 2C)。

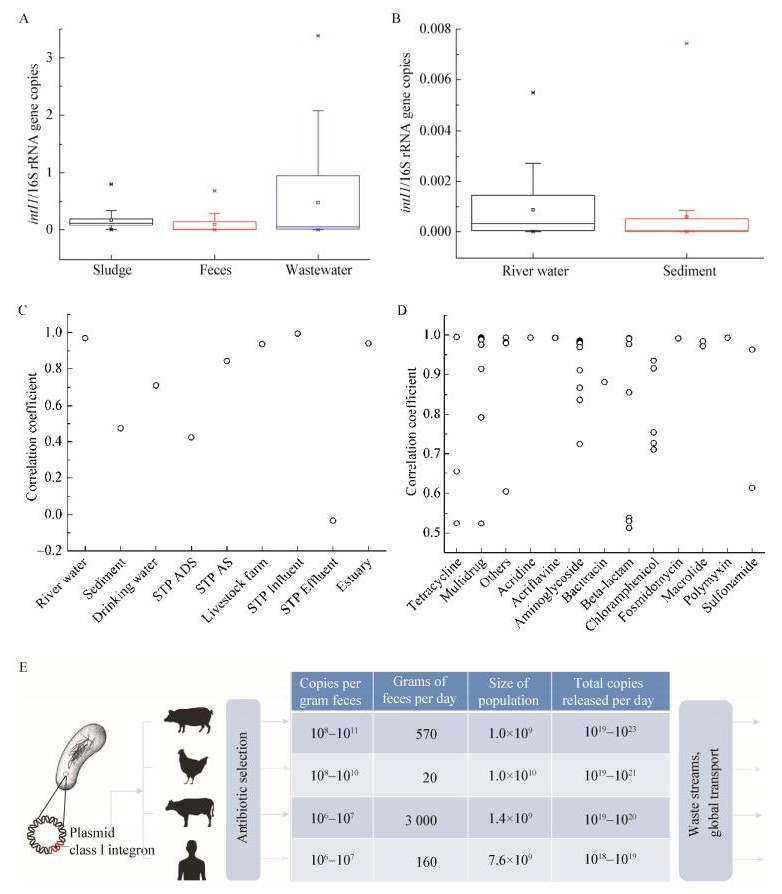

由于人及驯养陆地动物的生物量估计是野生陆生哺乳动物的35倍[80],且在使用大量抗生素的促进下,人和畜禽微生物组所携带的Int I具有很高的丰度[81]。这相当于每天都会有含量巨大的整合子通过粪便排出,每克粪便都存在数百万到数十亿拷贝数的intI1[82]。当然对于人和不同的畜禽来说,全球每天释放的intI1总拷贝数是有差别的,最高达到1023拷贝数,将会对全球ARGs的分布格局产生重要作用,并且这一作用会随着人口增长和畜禽养殖业发展而显著增强(图 3E)。高Int I丰度的人畜排泄物会以污水和肥料的形式扩散到更为复杂的自然环境中[82]。大量研究证明,Int I在环境中的分布与污染物排放、人类活动强度有密切关系。例如,Int I在污水处理中难以去除[83],通常在污水处理厂排水、污泥及下游的排水受纳区域丰度很高[84];在受人类活动影响的河流[85]、近海[86]环境中,intI1的丰度往往与重金属[87]、杀虫剂[88]、抗生素[89]及其他有机物污染水平呈正相关关系,也与ARGs[49]、重金属抗性基因[90]有强烈的共存关系。

|

| 图 3 Ⅰ型整合子的分布现状及其与抗性基因的关系 Figure 3 The distribution of class 1 integron and its relationship with ARGs 注:A:Ⅰ型整合子在不同污染排放系统中的相对丰度现状;B:Ⅰ型整合子在不同自然环境介质中的相对丰度现状;C:Ⅰ型整合子与不同环境中抗生素抗性基因的相关系数;D:Ⅰ型整合子与不同类别抗生素抗性基因的相关系数;E:全球人类活动导致Ⅰ型整合子排放的现状[82]. Note: A: The relative abundance of class 1 integron in different pollution discharge systems; B: The relative abundance of class 1 integron in different natural environment; C: The correlation of class 1 integron and ARGs in different environment; D: The correlation of class 1 integron and different classes ARGs; E: The status of class 1 integron emissions due to global human activities[82]. |

|

|

本文总结文献数据描述了intI1在粪便(包括人、猪、牛、鸡、鱼的粪便)、污泥(包括活性污泥和厌氧污泥)、废水、河水及沉积物等介质中的分布情况[82, 91-94](图 3A、B)。结果显示粪便、污泥、废水等介质中intI1的相对丰度(intI1/16S rRNA gene copies)要显著高于河水和沉积物等自然环境介质,两类介质相差几个数量级,这表明粪便、污泥、废水等是Int I的主要污染源。在粪便、污泥、废水三者中,intI1相对丰度也有所差异,污泥和废水中的intI1相对丰度高于粪便,原因是城市污水处理系统只能够有效降低大部分人畜排泄物中细菌丰度,但不会显著降低intI1的绝对丰度,因此处理过程会提高intI1的相对丰度[71, 93]。而在自然环境介质中,发现河水中intI1相对丰度要高于沉积物,表明水环境的Int I污染水平相对更为严重。

2.3 Ⅰ型整合子作为标记物在抗生素抗性基因研究中的应用近年来有研究者提出将Int I作为人类活动造成环境污染的一种标记物[67],原因如下:(1)从基因结构上,intI1与ARGs、重金属抗性基因、消毒剂抗性基因普遍存在联系;(2) Int I存在于多种动物和人体致病菌、寄生菌细胞内;(3) Int I多存在于可移动遗传元件或世代周期短的细菌,其传播速度快,丰度对环境变化响应敏感;(4)目前环境中普遍存在的intI1属于异型基因(Xenogene),即在近期人类活动形成的环境选择压力下进化组装而来。基于此,Int I在某种程度上可以反映人类活动对ARGs污染水平和分布格局的影响,同时表征不同ARGs在环境中的传播扩散规律,从而评估ARGs的潜在生态风险。

越来越多的研究关注Int I与ARGs的相关关系。在临床方面,主要是研究Int I与细菌多重耐药性的关系[95-96],发现携带有Int I的菌株要比不携带Int I的菌株更容易产生多重耐药性。Krauland等[97]对全球范围内整合子介导的沙门菌耐药性进行研究,结果表明整合子对沙门菌耐药基因在全球范围内克隆表达和水平转移发挥着重要作用;还有研究发现多重耐药鲍曼不动杆菌[98]的高度耐药性是因为Int I基因盒携带有9种不同的ARGs,有研究者甚至建议把Int I的存在作为鲍曼不动杆菌是否耐药的标志[99]。上述研究均表明细菌耐药性与Int I密切相关。

在自然或人工环境方面,研究专注于Int I在不同环境介质中介导ARGs传播扩散的作用,Ma等[91]应用高通量测序技术和宏基因组学分析,基于构建的intI1序列数据库和ARGs数据库,对Int I所携带基因盒上的ARGs进行了识别,针对8种生态系统的64个环境样本的研究结果显示:不同生态系统中的intI1与ARGs丰度之间都表现了较高的相关性(Pearson’s r=0.852),但不同生态系统之间也有较大差异,其中在污水处理厂出水中相关系数较低,而在污水处理厂进水、河水、畜禽养殖场等相关系数较高;其他研究结果表明河口环境[34]intI1与ARGs丰度之间也表现了很高的相关性(Pearson’s r=0.941)(图 3C)。挑选与intI1丰度相关系数 > 0.5的ARGs进行比较,一共49种亚型分属13类ARGs,结果发现Multidrug、Aminoglycoside、Beta-lactam等类别有较多ARGs丰度与intI1丰度相关系数高(图 3D)。

Nardelli等[100]研究了环境中intI1和ARGs的基因频率在不同城市化程度影响下的差异,结果表明Int I广泛分布在自然群落中且出现频率较高,但是与城市化程度没有显著相关关系,所研究的ARGs大部分都嵌入在Int I,其中sul1基因频率和城市化程度有关,qacE1/qacEΔ1基因在不同生境中扮演适应性角色。Borruso等[101]分析了受人类活动影响强烈区域intI1的分布,结果是携带有不同基因盒的Int I在农业区域表现出了较高的多样性,在国家公园区域没有检测到intI1及基因盒的存在。通过以上研究表明,intI1与ARGs丰度之间普遍存在着较高的相关性,可以表征不同ARGs在环境中传播的潜在风险,同时一定程度上反映了人类活动对自然环境微生物群落的干扰强度。

3 抗生素抗性基因与Ⅰ型整合子的研究方法 3.1 基于PCR的分子生物学分析方法一般来说,对于抗生素抗性的传统研究方法是基于微生物培养的药敏试验,通过抗性表型来评价其抗性[102]。但由于大量微生物难以进行培养,这会低估复杂微生物群落中抗性微生物的多样性,同时对整合子介导ARGs的传播过程无法跟踪检测。当前,分子生物学技术的发展和不断完善,在方法学上为ARGs和Int I的研究提供了极大可能。聚合酶链式反应(Polymerase chain reaction,PCR)技术可以对环境样本中的ARGs和Int I进行定性检测,该方法快速、灵敏、准确,在ARGs和Int I研究中应用非常广泛[24]。为了对基因丰度进行准确定量,目前广泛使用的是实时荧光定量PCR (qPCR)技术,利用荧光染料对PCR产物进行标记,从而通过检测被激发的荧光强度实现对ARGs和Int I的精确定量[103]。Zhang等[104]利用PCR和qPCR技术检测了垃圾渗滤液处理厂及其纳污土壤和地表水中的ARGs分布,结果发现经过对垃圾渗滤液的处理,ARGs丰度减少了2-4个数量级,纳污土壤主要的ARGs是tetB、sul2、tetA和tetX,纳污地表水中主要的ARGs是sul2和sul1。Hardwick等[103]利用qPCR技术定量研究了Int I在环境样本中的丰度,结果表明环境沉积物中intI1基因丰度与生态因素显著相关,暗示Int I提供了与环境压力相关的选择性优势,而不是抗生素的使用。Luo等[94]也利用PCR和qPCR技术检测了ARGs在天津海河的分布,结果没有检测到四环素类抗性基因,而sul2和sul1在所有样本中的浓度很高,且其在沉积物的浓度是水中的120-2 000倍。同时,作为PCR技术的补充,PCR-变性梯度凝胶电泳(PCR-DGGE)、DNA杂交技术[105]和DNA芯片技术[106]等被用于对环境样品中ARGs检测的部分研究。

此外,环介导等温扩增方法(Loop-mediated isothermal amplification,LAMP)[7]和高通量实时荧光定量PCR技术[107](High-throughput real-time PCR,HT-qPCR)在近年内有所应用,并呈现快速发展的趋势。其中,LAMP是利用4个特殊设计的引物和具有链置换活性的DNA聚合酶在恒温条件下特异、高效、快速扩增DNA的新技术,该方法适用于更小提取量DNA的扩增[108]。比如在Int I丰度较低的自然环境中,相对于qPCR,LAMP方法得到的intI1基因相对丰度与ARGs丰度的相关系数更高[7]。而HT-qPCR是在荧光定量PCR基础上,同时检测更多样品或者基因的表达分析技术,拥有自动化程度高、低污染、高通量等特点,WaferGen Biosystems公司开发的SmartChip高通量实时荧光定量PCR系统可同时完成多达5 184个独立的扩增反应。对ARGs分析来说,可同时对上百种ARGs或多个样品进行定量分析,比如将HT-qPCR应用于河口环境样品的研究中,可以检测并定量285种ARGs,这些ARGs涵盖了目前已知的主要ARGs类型[34]。

3.2 基于高通量测序的组学分析方法随着测序技术的不断发展和成熟,研究者可以采用直接测序的方法对环境DNA进行测序,并通过序列比对来鉴定ARGs和Int I。高通量测序技术为探索不同环境中ARGs和Int I的分布及多样性提供了有力支持,也推动ARGs和Int I研究进入了组学时代,相继有学者提出了抗生素抗性组(Antibiotic resistome)[109-111]和可移动抗生素抗性组(Antibiotic resistance mobilome)[112]的概念。抗生素抗性组是指环境微生物基因组中所有ARGs的集合,而可移动抗生素抗性组则是指环境微生物基因组中所有可移动遗传元件的集合。通过构建肠道[113]、土壤[114]等微生物宏基因组文库进行抗生素的功能筛选,并对筛选得到的抗性克隆子进行测序,所发现的大部分ARGs与已知数据库中的ARGs不同,这就暗示着环境中ARGs种类和丰度远远超出人们的预料。同时还发现许多非致病菌ARGs与致病菌可移动遗传元件区的核酸序列高度相似,有力地证实了环境细菌和致病菌之间存在着ARGs的交换和转移[45]。

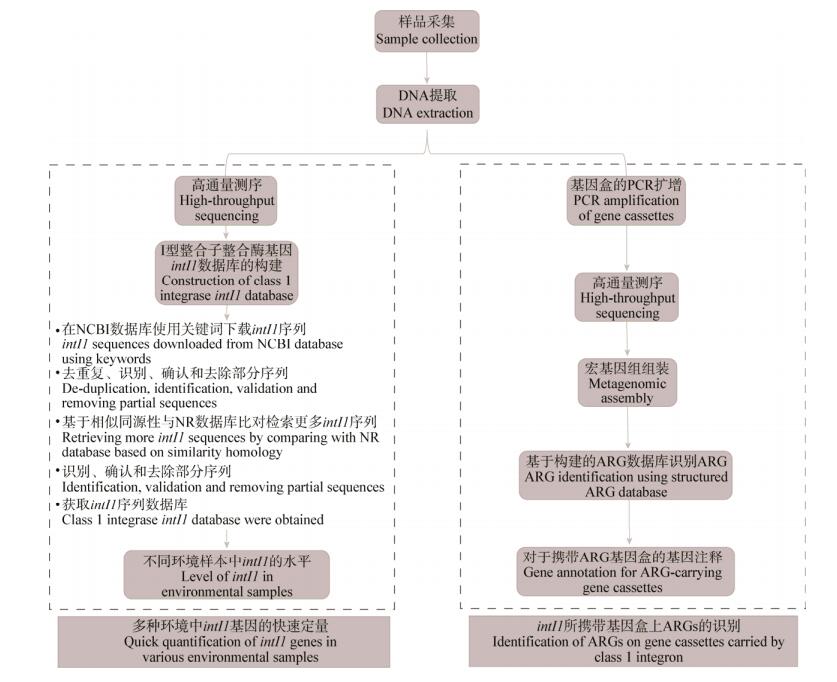

目前对于ARGs和可移动遗传元件的组学研究,已经有许多数据库和分析平台可以使用[115](表 1),也有研究对不同数据及分析工具的优劣进行了比较[116-117]。现在应用较为广泛的是ARDB[118]和CARD等ARGs数据库,还有INTEGRALL和IntegronFinder等整合子分析工具。比如,Yang等[119]利用宏基因组学方法对ARGs在污水处理厂各个过程的迁移转化进行了调查,结果总计检测到271类ARGs,其中有78种ARGs在生物处理之后依然残留,且污泥处理中ARGs的去除效率不如废水处理;Tian等[89]利用宏基因组学方法研究了从中温到高温厌氧消化污泥中抗生素抗性组和可移动抗生素抗性组的变化,结果发现在高温条件下ARGs水平转移的潜在风险更低。但对于环境中Int I的鉴别来说,INTEGRALL[120]和Integron Finder[121]只能针对细菌的全基因组、基因组草图和长片段拼接序列来分析,而对宏基因组测序中的短片段序列(100-150 bp)则无法准确注释。因此,又有研究者针对ARGs和Int I的宏基因组学研究提出了一套切实可行的方法[91](图 4),主要就是重新构建了intI1基因数据库,同时结合已有的ARGs数据库,对不同环境样本中intI1及其携带的ARGs种类和丰度进行了鉴别和定量。还有研究则基于环境抗生素抗性组数据建立数学模型,设置模型中关键的生物、空间和化学变量,旨在评估和预测ARGs传播和扩散的风险水平[122]。

| 分类Classification | 资源Resource | 网站Website |

| 抗生素抗性 Antibiotic resistance |

抗生素抗性基因数据库ARDB (Antibiotic resistance gene database) | http://ardb.cbcb.umd.edu/ |

| 综合抗生素抗性数据库 CARD (Comprehensive antibiotic resistance database) |

https://card.mcmaster.ca/ | |

| 抗生素抗性基因盒的资源库 RAC (Repository of antibiotic resistance cassettes) |

http://rac.aihi.mq.edu.au/rac/ | |

| 抗性基因检测 ResFinder (Resistance gene finder) |

https://cge.cbs.dtu.dk/services/ResFinder/ | |

| 抗生素抗性功能 ResFams (Antibiotic resistance function) |

http://www.dantaslab.org/resfams/ | |

| 抗生素抗性基因注释 ARG-ANNOT (Antibiotic resistance gene annotation) |

http://en.mediterranee-infection.com/article.php?laref=283%26titre=arg-annot | |

| 其他抗性和毒性因素 Other resistance and virulence determinants |

毒性因子和毒素 MvirDB (Virulence factors and toxins) |

http://mvirdb.llnl.gov/ |

| 寄生致病系统资源整合中心 PATRIC (Pathosystems resource integration center) |

https://www.patricbrc.org/portal/portal/patric/Home# | |

| 生物杀菌剂和金属抗性基因 BacMet (Biocide and metal resistance genes) |

http://bacmet.biomedicine.gu.se/ | |

| 外排泵-综述 Efflux pumps (Review) |

http://cmr.asm.org/content/28/2/337.short | |

| 载体和可移动遗传元件 Vectors and mobile elements |

整合子数据库 INTEGRALL (The integron database) |

http://integrall.bio.ua.pt/ |

| 整合子检测 Integron Finder |

https://github.com/gem-pasteur/Integron_Finder | |

| 噬菌体,质粒和转座子 ACLAME (Phages, plasmids, and transposons) |

http://aclame.ulb.ac.be/ | |

| 插入元件检测 IS Finder (Insertion element finder) |

https://www-is.biotoul.fr/ | |

| 综合共轭元件分析 ICEBerg (Integrative conjugative element analysis) |

http://db-mml.sjtu.edu.cn/ICEberg/ | |

| 基因组岛预测 IslandViewer (Genomic island prediction) |

http://www.pathogenomics.sfu.ca/islandviewer/ | |

| 毒力岛数据库 PAIDB (Pathogenicity island database) |

http://www.paidb.re.kr/about_paidb.php | |

| 质粒生物信息检测 PlasmidFinder (In silico plasmid detection) |

https://cge.cbs.dtu.dk/services/PlasmidFinder/ |

总之,基于高通量测序的组学分析方法虽然高度依赖现有数据库的完善程度,但也在很大程度上避免了传统分子生物学方法在克隆偏好和异源表达方面的缺陷,并可对不同环境中的ARGs及其相关可移动遗传元件的丰度和多样性进行比较,极大地拓展了ARGs水平转移传播机制的研究,是未来一段时间内的发展方向。

4 结论与展望目前医用和兽用抗生素长时间的滥用问题已经非常严重,造成了ARGs在人体和环境中的种类、分布情况被人为改变,其潜在的环境和健康风险需要引起科学家、政府和公众的广泛重视。现在可以认识到Int I对ARGs在环境中的传播和扩散发挥了重要作用,是环境微生物产生耐药性的重要途径,其携带的多种ARGs可能会被整合到一些致病菌的基因组,从而对人体健康造成危害。但是,现在对抗生素及其抗性基因的环境行为和风险评估的研究尚不完善,Int I和ARGs的迁移转化规律和内在机制的研究尚不系统,因此未来研究应加强以下三方面工作:

(1) 采用HT-qPCR等多种分子生物学技术,并结合基于高通量测序的组学分析方法,对不同环境介质中的Int I和ARGs丰度进行监测,获得更加系统的Int I和ARGs环境分布数据,并利用数学模型模拟等多种手段进行溯源,从而制定相应策略开展源头管控;

(2) 进一步研究ARGs在环境中的传播和扩散规律,尤其明确Int I在这一过程中的作用,可以在分子、个体、群落等不同水平开展机理研究,同时分析抗生素、温度、pH等环境因子对Int I和ARGs传播扩散的影响及其机制,最终评估Int I和ARGs传播扩散对环境微生物群落进化和多样性的影响水平;

(3) 开展Int I和ARGs的去除研究,目标是利用多种处理技术进行源头排放的控制,降低Int I和ARGs在环境中的残留丰度,同时针对基因组学技术发现的大量新型ARGs,深入探讨其内在的抗性机制,促进新型抗生素的研发工作或者其他基因靶向治疗的研究,这对保障人类健康具有重要意义。

| [1] |

Luo Y, Zhou QX. Antibiotic resistance genes (ARGs) as emerging pollutants[J]. Acta Scientiae Circumstantiae, 2008, 28(8): 1499-1505. (in Chinese) 罗义, 周启星. 抗生素抗性基因(ARGs)——一种新型环境污染物[J]. 环境科学学报, 2008, 28(8): 1499-1505. DOI:10.3321/j.issn:0253-2468.2008.08.002 |

| [2] |

Ochman H, Lawrence JG, Groisman EA. Lateral gene transfer and the nature of bacterial innovation[J]. Nature, 2000, 405(6784): 299-304. |

| [3] |

Brown JR. Ancient horizontal gene transfer[J]. Nature Reviews Genetics, 2003, 4(2): 121-132. DOI:10.1038/nrg1000 |

| [4] |

Palumbi SR. The Evolution Explosion[M]. Beijing: China Environmental Science Press, 2008. 帕卢比. 进化爆炸[M]. 北京: 中国环境科学出版社, 2008. |

| [5] |

Stokes HW, Hall RM. A novel family of potentially mobile DNA elements encoding site-specific gene-integration functions: integrons[J]. Molecular Microbiology, 1989, 3(12): 1669-1683. |

| [6] |

Gaze WH, Zhang LH, Abdouslam NA, et al. Impacts of anthropogenic activity on the ecology of class 1 integrons and integron-associated genes in the environment[J]. The ISME Journal, 2011, 5(8): 1253-1261. DOI:10.1038/ismej.2011.15 |

| [7] |

Stedtfeld RD, Stedtfeld TM, Waseem H, et al. Isothermal assay targeting class 1 integrase gene for environmental surveillance of antibiotic resistance markers[J]. Journal of Environmental Management, 2017, 198: 213-220. DOI:10.1016/j.jenvman.2017.04.079 |

| [8] |

Aminov RI. The role of antibiotics and antibiotic resistance in nature[J]. Environmental Microbiology, 2009, 11(12): 2970-2988. DOI:10.1111/emi.2009.11.issue-12 |

| [9] |

Zhou ZH, Wu QZ, Wang XJ, et al. A review on present situation and detection technology of antibiotics pollution in environment[J]. Analytical Instrumentation, 2016(6): 1-8. (in Chinese) 周志洪, 吴清柱, 王秀娟, 等. 环境中抗生素污染现状及检测技术[J]. 分析仪器, 2016(6): 1-8. |

| [10] |

Davies J. Microbes have the last word: A drastic re-evaluation of antimicrobial treatment is needed to overcome the threat of antibiotic-resistant bacteria[J]. EMBO Reports, 2007, 8(7): 616-621. DOI:10.1038/sj.embor.7401022 |

| [11] |

Gao LH, Shi YL, Li WH, et al. Environmental behavior and impacts of antibiotics[J]. Environmental Chemistry, 2013, 32(9): 1619-1633. (in Chinese) 高立红, 史亚利, 厉文辉, 等. 抗生素环境行为及其环境效应研究进展[J]. 环境化学, 2013, 32(9): 1619-1633. |

| [12] |

Zhou QX, Luo Y, Wang ME. Environmental residues and ecotoxicity of antibiotics and their resistance gene pollution: a review[J]. Asian Journal of Ecotoxicology, 2007, 2(3): 243-251. (in Chinese) 周启星, 罗义, 王美娥. 抗生素的环境残留、生态毒性及抗性基因污染[J]. 生态毒理学报, 2007, 2(3): 243-251. |

| [13] |

Zhang QQ, Ying GG, Pan CG, et al. Comprehensive evaluation of antibiotics emission and fate in the River Basins of China: Source analysis, multimedia modeling, and linkage to bacterial resistance[J]. Environmental Science & Technology, 2015, 49(11): 6772-6782. |

| [14] |

Alekshun MN, Levy SB. Molecular mechanisms of antibacterial multidrug resistance[J]. Cell, 2007, 128(6): 1037-1050. DOI:10.1016/j.cell.2007.03.004 |

| [15] |

Davies J, Davies D. Origins and evolution of antibiotic resistance[J]. Microbiology and Molecular Biology Reviews, 2010, 74(3): 417-433. DOI:10.1128/MMBR.00016-10 |

| [16] |

Martínez JL. Antibiotics and antibiotic resistance genes in natural environments[J]. Science, 2008, 321(5887): 365-367. DOI:10.1126/science.1159483 |

| [17] |

D'-Costa VM, King CE, Kalan L, et al. Antibiotic resistance is ancient[J]. Nature, 2011, 477(7365): 457-461. |

| [18] |

Knapp CW, Dolfing J, Ehlert PAI, et al. Evidence of increasing antibiotic resistance gene abundances in archived soils since 1940[J]. Environmental Science & Technology, 2010, 44(2): 580-587. |

| [19] |

Armstrong GL, Pinner RW. Outpatient visits for infectious diseases in the United States, 1980 through 1996[J]. Archives of Internal Medicine, 1999, 159(21): 2531-2536. |

| [20] |

Tian BY, Ma RQ. Antibiotic resistances in environmental microbiota and antibiotic resistome[J]. China Biotechnology, 2015, 35(10): 108-114. (in Chinese) 田宝玉, 马荣琴. 环境微生物的抗生素抗性和抗性组[J]. 中国生物工程杂志, 2015, 35(10): 108-114. |

| [21] |

Mahy BW. The global threat of emerging infectious diseases[J]. Israel Medical Association Journal, 2000, 2(Suppl.): 23-26. |

| [22] |

Su JQ, Huang FY, Zhu YG. Antibiotic resistance genes in the environment[J]. Biodiversity Science, 2013, 21(4): 481-487. (in Chinese) 苏建强, 黄福义, 朱永官. 环境抗生素抗性基因研究进展[J]. 生物多样性, 2013, 21(4): 481-487. |

| [23] |

Shi MW, Zhu XL, Tang WZ. Progress in research of the environmental effects of antibiotic resistance genes[J]. Environmental Protection Science, 2015, 41(6): 123-128. (in Chinese) 史密伟, 朱晓磊, 唐文忠. 抗生素抗性基因环境效应的研究进展[J]. 环境保护科学, 2015, 41(6): 123-128. DOI:10.3969/j.issn.1004-6216.2015.06.026 |

| [24] |

Wang LM, Luo Y, Mao DQ, et al. Transport of antibiotic resistance genes in environment and detection methods of antibiotic resistance[J]. Chinese Journal of Applied Ecology, 2010, 21(4): 1063-1069. (in Chinese) 王丽梅, 罗义, 毛大庆, 等. 抗生素抗性基因在环境中的传播扩散及抗性研究方法[J]. 应用生态学报, 2010, 21(4): 1063-1069. |

| [25] |

Pruden A, Pei RT, Storteboom H, et al. Antibiotic resistance genes as emerging contaminants: studies in northern Colorado[J]. Environmental Science & Technology, 2006, 40(23): 7445-7450. |

| [26] |

Chee-Sanford JC, Aminov RI, Krapac IJ, et al. Occurrence and diversity of tetracycline resistance genes in lagoons and groundwater underlying two swine production facilities[J]. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 2001, 67(4): 1494-1502. |

| [27] |

Watts JEM, Schreier HJ, Lanska L, et al. The rising tide of antimicrobial resistance in aquaculture: Sources, sinks and solutions[J]. Marine Drugs, 2017, 15(6): 158. DOI:10.3390/md15060158 |

| [28] |

Auerbach EA, Seyfried EE, McMahon KD. Tetracycline resistance genes in activated sludge wastewater treatment plants[J]. Water Research, 2007, 41(5): 1143-1151. DOI:10.1016/j.watres.2006.11.045 |

| [29] |

Karkman A, Do TT, Walsh F, et al. Antibiotic-resistance genes in waste water[J]. Trends in Microbiology, 2018, 26(3): 220-228. DOI:10.1016/j.tim.2017.09.005 |

| [30] |

Su JQ, An XL, Li B, et al. Metagenomics of urban sewage identifies an extensively shared antibiotic resistome in China[J]. Microbiome, 2017, 5(1): 84. |

| [31] |

Zhang Y, Li AL, Dai TJ, et al. Cell-free DNA: a neglected source for antibiotic resistance genes spreading from WWTPs[J]. Environmental Science & Technology, 2018, 52(1): 248-257. |

| [32] |

Zhang Y, Chen LJ, Xie H, et al. Abundance of cell-associated and cell-free antibiotic resistance genes in two wastewater treatment systems[J]. Environmental Science, 2017, 38(9): 3823-3830. (in Chinese) 张衍, 陈吕军, 谢辉, 等. 两座污水处理系统中细胞态和游离态抗生素抗性基因的丰度特征[J]. 环境科学, 2017, 38(9): 3823-3830. |

| [33] |

Ouyang WY, Huang FY, Zhao Y, et al. Increased levels of antibiotic resistance in urban stream of Jiulongjiang River, China[J]. Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology, 2015, 99(13): 5697-5707. DOI:10.1007/s00253-015-6416-5 |

| [34] |

Zhu YG, Zhao Y, Li B, et al. Continental-scale pollution of estuaries with antibiotic resistance genes[J]. Nature Microbiology, 2017, 2: 16270. DOI:10.1038/nmicrobiol.2016.270 |

| [35] |

Czekalski N, Díez EG, Bürgmann H. Wastewater as a point source of antibiotic-resistance genes in the sediment of a freshwater lake[J]. The ISME Journal, 2014, 8(7): 1381-1390. DOI:10.1038/ismej.2014.8 |

| [36] |

Gou M, Hu HW, Zhang YJ, et al. Aerobic composting reduces antibiotic resistance genes in cattle manure and the resistome dissemination in agricultural soils[J]. Science of the Total Environment, 2018, 612: 1300-1310. DOI:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2017.09.028 |

| [37] |

Jin ML, Meng QL, Zhao YX, et al. Characterization of sulfa antibiotics resistance of E. coli from the air of poultry farms[J]. Environmental Chemistry, 2017, 36(3): 472-479. (in Chinese) 金明兰, 孟庆玲, 赵玉鑫, 等. 养殖场空气中E. coli磺胺类抗生素的抗性[J]. 环境化学, 2017, 36(3): 472-479. |

| [38] |

He XM, Cao G, Shao MF, et al. Research method and progress on antibiotics resistance genes (ARGs) in air[J]. Environmental Chemistry, 2014, 33(5): 739-747. (in Chinese) 贺小萌, 曹罡, 邵明非, 等. 空气中抗性基因(ARGs)的研究方法及研究进展[J]. 环境化学, 2014, 33(5): 739-747. |

| [39] |

Allen HK, Donato J, Wang HH, et al. Call of the wild: antibiotic resistance genes in natural environments[J]. Nature Reviews Microbiology, 2010, 8(4): 251-259. |

| [40] |

Zhu YG, Ouyang WY, Wu N, et al. Antibiotic resistance: sources and mitigation[J]. Bulletin of Chinese Academy of Sciences, 2015, 30(4): 509-516. (in Chinese) 朱永官, 欧阳纬莹, 吴楠, 等. 抗生素耐药性的来源与控制对策[J]. 中国科学院院刊, 2015, 30(4): 509-516. |

| [41] |

Yang FX, Mao DQ, Luo Y, et al. Horizontal transfer of antibiotic resistance genes in the environment[J]. Chinese Journal of Applied Ecology, 2013, 24(10): 2993-3002. (in Chinese) 杨凤霞, 毛大庆, 罗义, 等. 环境中抗生素抗性基因的水平传播扩散[J]. 应用生态学报, 2013, 24(10): 2993-3002. |

| [42] |

Wright GD. Antibiotic resistance in the environment: a link to the clinic?[J]. Current Opinion in Microbiology, 2010, 13(5): 589-594. DOI:10.1016/j.mib.2010.08.005 |

| [43] |

Xu BJ, Luo Y, Zhou QX, et al. Sources, dissemination, and ecological risks of antibiotic resistances genes (ARGs) in the environment[J]. Environmental Chemistry, 2010, 29(2): 169-178. (in Chinese) 徐冰洁, 罗义, 周启星, 等. 抗生素抗性基因在环境中的来源、传播扩散及生态风险[J]. 环境化学, 2010, 29(2): 169-178. |

| [44] |

Smillie CS, Smith MB, Friedman J, et al. Ecology drives a global network of gene exchange connecting the human microbiome[J]. Nature, 2011, 480(7376): 241-244. |

| [45] |

Forsberg KJ, Reyes A, Wang B, et al. The shared antibiotic resistome of soil bacteria and human pathogens[J]. Science, 2012, 337(6098): 1107-1111. DOI:10.1126/science.1220761 |

| [46] |

Mcgowan LL, Jackson CR, Barrett JB, et al. Prevalence and antimicrobial resistance of enterococci isolated from retail fruits, vegetables, and meats[J]. Journal of Food Protection, 2006, 69(12): 2976-2982. |

| [47] |

Wang SL, Wang L, Zhou H, et al. An overview on antibiotic resistance genes in drinking water systems[J]. Environmental Chemistry, 2017, 36(2): 229-240. (in Chinese) 王双玲, 王礼, 周贺, 等. 饮用水系统中抗生素抗性基因的研究进展[J]. 环境化学, 2017, 36(2): 229-240. |

| [48] |

Esiobu N, Armenta L, Ike J. Antibiotic resistance in soil and water environments[J]. International Journal of Environmental Health Research, 2002, 12(2): 133-144. DOI:10.1080/09603120220129292 |

| [49] |

Zhu YG, Johnson TA, Su JQ, et al. Diverse and abundant antibiotic resistance genes in Chinese swine farms[J]. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 2013, 110(9): 3435-3440. DOI:10.1073/pnas.1222743110 |

| [50] |

Gupta N, Limbago BM, Patel JB, et al. Carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae: epidemiology and prevention[J]. Clinical Infectious Diseases, 2011, 53(1): 60-67. DOI:10.1093/cid/cir202 |

| [51] |

Liu YY, Wang Y, Walsh TR, et al. Emergence of plasmid-mediated colistin resistance mechanism MCR-1 in animals and human beings in China: a microbiological and molecular biological study[J]. The Lancet Infectious Diseases, 2016, 16(2): 161-168. DOI:10.1016/S1473-3099(15)00424-7 |

| [52] |

Wang Y, Zhang R, Li J, et al. Comprehensive resistome analysis reveals the prevalence of NDM and mcr-1 in Chinese poultry production[J]. Nature Microbiology, 2017, 2(4): 16260. DOI:10.1038/nmicrobiol.2016.260 |

| [53] |

Shen YW, Huang ZT, Xie B. Advances in research of pollution, degradation and removal of antibiotics and antibiotic resistance genes in the environment[J]. Chinese Journal of Applied & Environmental Biology, 2015, 21(2): 181-187. 沈怡雯, 黄智婷, 谢冰. 抗生素及其抗性基因在环境中的污染、降解和去除研究进展[J]. 应用与环境生物学报, 2015, 21(2): 181-187. |

| [54] |

Börjesson S, Mattsson A, Lindgren PE. Genes encoding tetracycline resistance in a full-scale municipal wastewater treatment plant investigated during one year[J]. Journal of Water and Health, 2010, 8(2): 247-256. |

| [55] |

Guo MT, Yuan QB, Yang J. Ultraviolet reduction of erythromycin and tetracycline resistant heterotrophic bacteria and their resistance genes in municipal wastewater[J]. Chemosphere, 2013, 93(11): 2864-2868. DOI:10.1016/j.chemosphere.2013.08.068 |

| [56] |

Sharma VK, Johnson N, Cizmas L, et al. A review of the influence of treatment strategies on antibiotic resistant bacteria and antibiotic resistance genes[J]. Chemosphere, 2016, 150: 702-714. |

| [57] |

Guo MT, Yuan QB, Yang J. Distinguishing effects of ultraviolet exposure and chlorination on the horizontal transfer of antibiotic resistance genes in municipal wastewater[J]. Environmental Science & Technology, 2015, 49(9): 5771-5778. |

| [58] |

Zhang YY, Zhuang Y, Geng JJ, et al. Reduction of antibiotic resistance genes in municipal wastewater effluent by advanced oxidation processes[J]. Science of the Total Environment, 2016, 550: 184-191. DOI:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2016.01.078 |

| [59] |

Guo CS, Wang K, Hou S, et al. H2O2 and/or TiO2 photocatalysis under UV irradiation for the removal of antibiotic resistant bacteria and their antibiotic resistance genes[J]. Journal of Hazardous Materials, 2017, 323: 710-718. DOI:10.1016/j.jhazmat.2016.10.041 |

| [60] |

Moreira NFF, Sousa JM, Macedo G, et al. Photocatalytic ozonation of urban wastewater and surface water using immobilized TiO2 with LEDs: Micropollutants, antibiotic resistance genes and estrogenic activity[J]. Water Research, 2016, 94: 10-22. DOI:10.1016/j.watres.2016.02.003 |

| [61] |

Mehrjouei M, Mueller S, Moeller D. A review on photocatalytic ozonation used for the treatment of water and wastewater[J]. Chemical Engineering Journal, 2015, 263: 209-219. DOI:10.1016/j.cej.2014.10.112 |

| [62] |

Chen H, Zhang MM. Effects of advanced treatment systems on the removal of antibiotic resistance genes in wastewater treatment plants from Hangzhou, China[J]. Environmental Science & Technology, 2013, 47(15): 8157-8163. |

| [63] |

Chen J, Ying GG, Wei XD, et al. Removal of antibiotics and antibiotic resistance genes from domestic sewage by constructed wetlands: Effect of flow configuration and plant species[J]. Science of the Total Environment, 2016, 571: 974-982. DOI:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2016.07.085 |

| [64] |

Zhang ZY, Liu SW, Zhang L. Removal of sulfonamide resistance genes in livestock farms with constructed wetland[J]. Environmental Science and Management, 2016, 41(5): 89-92. (in Chinese) 张子扬, 刘舒巍, 张璐. 人工湿地去除畜禽养殖废水中磺胺类抗生素抗性基因研究[J]. 环境科学与管理, 2016, 41(5): 89-92. DOI:10.3969/j.issn.1673-1212.2016.05.022 |

| [65] |

Zheng JY, Liu L, Gao DW, et al. Removal and accumulation of the tetracycline resistance gene in vertical flow constructed wetland[J]. Environmental Science, 2013, 34(8): 3102-3107. (in Chinese) 郑加玉, 刘琳, 高大文, 等. 四环素抗性基因在人工湿地中的去除及累积[J]. 环境科学, 2013, 34(8): 3102-3107. |

| [66] |

Qin CX, Tong J, Shen PH, et al. Integron-containing antibiotic resistant bacteria wastewater treatment processes: an overview[J]. Environmental Science & Technology, 2015, 38(11): 1-7. (in Chinese) 覃彩霞, 佟娟, 申佩弘, 等. 污水处理过程中细菌整合子的研究进展[J]. 环境科学与技术, 2015, 38(11): 1-7. |

| [67] |

Gillings MR, Gaze WH, Pruden A, et al. Using the class 1 integron-integrase gene as a proxy for anthropogenic pollution[J]. The ISME Journal, 2015, 9(6): 1269-1279. |

| [68] |

Boucher Y, Labbate M, Koenig JE, et al. Integrons: mobilizable platforms that promote genetic diversity in bacteria[J]. Trends in Microbiology, 2007, 15(7): 301-309. |

| [69] |

Collis CM, Hall RM. Expression of antibiotic resistance genes in the integrated cassettes of integrons[J]. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy, 1995, 39(1): 155-162. DOI:10.1128/AAC.39.1.155 |

| [70] |

Partridge SR, Tsafnat G, Coiera E, et al. Gene cassettes and cassette arrays in mobile resistance integrons[J]. FEMS Microbiology Reviews, 2009, 33(4): 757-784. |

| [71] |

Gillings MR. Class 1 integrons as invasive species[J]. Current Opinion in Microbiology, 2017, 38: 10-15. |

| [72] |

Gillings MR. Integrons: past, present, and future[J]. Microbiology and Molecular Biology Reviews, 2014, 78(2): 257-277. |

| [73] |

Gillings M, Boucher Y, Labbate M, et al. The evolution of class 1 integrons and the rise of antibiotic resistance[J]. Journal of Bacteriology, 2008, 190(14): 5095-5100. |

| [74] |

Wei QH, Jiang XF, Lv Y. Advances in integrons of bacteria[J]. Chinese Journal of Antibiotics, 2008, 33(1): 1-5, 40. (in Chinese) 魏取好, 蒋晓飞, 吕元. 细菌整合子研究进展[J]. 中国抗生素杂志, 2008, 33(1): 1-5, 40. |

| [75] |

Li YM, Zhao XH, Xu ZZ, et al. Novel antibiotic resistance mechanism-integron system[J]. Chinese Journal of Antibiotics, 2012, 37(1): 1-7. (in Chinese) 李彦媚, 赵喜红, 徐泽智, 等. 新型细菌耐药元件——整合子系统[J]. 中国抗生素杂志, 2012, 37(1): 1-7. DOI:10.3969/j.issn.1001-8689.2012.01.001 |

| [76] |

Huang XR, Liu PC, Cai RZ, et al. Antimicrobial resistance analysis on clinically isolated Escherichia coli and detection of class I integrons[J]. Chinese Journal of Infection Control, 2014, 13(9): 524-529. (in Chinese) 黄小荣, 刘配辰, 蔡瑞昭, 等. 临床分离大肠埃希菌耐药性分析及Ⅰ型整合子研究[J]. 中国感染控制杂志, 2014, 13(9): 524-529. DOI:10.3969/j.issn.1671-9638.2014.09.003 |

| [77] |

Huang J, Wang X, Wu ZY, et al. Detection and analysis of class Ⅰ integron-gene cassettes in multi-drug resistant pseudomonas aeruginosa[J]. Progress in Microbiology and Immunology, 2017, 45(5): 21-24. (in Chinese) 黄娟, 王欣, 吴志毅, 等. 多重耐药铜绿假单胞菌Ⅰ类整合子-基因盒的检测与分析[J]. 微生物学免疫学进展, 2017, 45(5): 21-24. |

| [78] |

Sun GM. Study on the acquired resistance mechanisms of Pseudomonas aeruginosa mediated by integrons[D]. Zhenjiang: Doctoral Dissertation of Jiangsu University, 2013 (in Chinese) 孙光明.整合子介导铜绿假单胞菌获得性耐药机制的研究[D].镇江: 江苏大学博士学位论文, 2013 |

| [79] |

Deng YT, Wu YL, Jiang L, et al. Multi-drug resistance mediated by class 1 integrons in Aeromonas isolated from farmed freshwater animals[J]. Frontiers in Microbiology, 2016, 7: 935. |

| [80] |

Smil V. Harvesting the biosphere: The human impact[J]. Population and Development Review, 2011, 37(4): 613-636. DOI:10.1111/padr.2011.37.issue-4 |

| [81] |

Sandberg KD, LaPara TM. The fate of antibiotic resistance genes and class 1 integrons following the application of swine and dairy manure to soils[J]. FEMS Microbiology Ecology, 2016, 92(2): fiw001. DOI:10.1093/femsec/fiw001 |

| [82] |

Zhu YG, Gillings M, Simonet P, et al. Microbial mass movements[J]. Science, 2017, 357(6356): 1099-1100. DOI:10.1126/science.aao3007 |

| [83] |

Du J, Ren HQ, Geng JJ, et al. Occurrence and abundance of tetracycline, sulfonamide resistance genes, and class 1 integron in five wastewater treatment plants[J]. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 2014, 21(12): 7276-7284. |

| [84] |

Stalder T, Barraud O, Jové T, et al. Quantitative and qualitative impact of hospital effluent on dissemination of the integron pool[J]. The ISME Journal, 2014, 8(4): 768-777. DOI:10.1038/ismej.2013.189 |

| [85] |

Khan GA, Berglund B, Khan KM, et al. Occurrence and abundance of antibiotics and resistance genes in rivers, canal and near drug formulation facilities — a study in Pakistan[J]. PLoS One, 2013, 8(6): e62712. |

| [86] |

Muziasari WI, Pärnänen K, Johnson TA, et al. Aquaculture changes the profile of antibiotic resistance and mobile genetic element associated genes in Baltic Sea sediments[J]. FEMS Microbiology Ecology, 2016, 92(4): fiw052. DOI:10.1093/femsec/fiw052 |

| [87] |

Knapp CW, McCluskey SM, Singh BK, et al. Antibiotic resistance gene abundances correlate with metal and geochemical conditions in archived Scottish soils[J]. PLoS One, 2011, 6(11): e27300. |

| [88] |

Dealtry S, Ding GC, Weichelt V, et al. Cultivation-independent screening revealed hot spots of IncP-1, IncP-7 and IncP-9 plasmid occurrence in different environmental habitats[J]. PLoS One, 2014, 9(2): e89922. |

| [89] |

Tian Z, Zhang Y, Yu B, et al. Changes of resistome, mobilome and potential hosts of antibiotic resistance genes during the transformation of anaerobic digestion from mesophilic to thermophilic[J]. Water Research, 2016, 98: 261-269. DOI:10.1016/j.watres.2016.04.031 |

| [90] |

Seiler C, Berendonk TU. Heavy metal driven co-selection of antibiotic resistance in soil and water bodies impacted by agriculture and aquaculture[J]. Frontiers in Microbiology, 2012, 3: 399. |

| [91] |

Ma LP, Li AD, Yin XL, et al. The prevalence of integrons as the carrier of antibiotic resistance genes in natural and man-made environments[J]. Environmental Science & Technology, 2017, 51(10): 5721-5728. |

| [92] |

Liu MM, Ding R, Zhang Y, et al. Abundance and distribution of Macrolide-Lincosamide-Streptogramin resistance genes in an anaerobic-aerobic system treating spiramycin production wastewater[J]. Water Research, 2014, 63: 33-41. DOI:10.1016/j.watres.2014.05.045 |

| [93] |

Makowska N, Koczura R, Mokracka J. Class 1 integrase, sulfonamide and tetracycline resistance genes in wastewater treatment plant and surface water[J]. Chemosphere, 2016, 144: 1665-1673. DOI:10.1016/j.chemosphere.2015.10.044 |

| [94] |

Luo Y, Mao DQ, Rysz M, et al. Trends in antibiotic resistance genes occurrence in the Haihe River, China[J]. Environmental Science & Technology, 2010, 44(19): 7220-7225. |

| [95] |

Li LM, Yuan XY, Wang MY, et al. The integron-gene cassette system and the mechanism of bacterial drug resistance: research progress[J]. Chinese Journal of Microecology, 2014, 26(2): 246-248. (in Chinese) 李鲁明, 袁晓燕, 王明义, 等. 整合子-基因盒系统与细菌耐药机制的研究进展[J]. 中国微生态学杂志, 2014, 26(2): 246-248. |

| [96] |

Hu XH, Li GM. Advances in the relationship between integrons and drug resistance of bacteria[J]. World Notes on Antibiotics, 2009, 30(6): 255-259. (in Chinese) 胡小行, 李国明. 整合子与细菌耐药性关系的研究进展[J]. 国外医药(抗生素分册), 2009, 30(6): 255-259. |

| [97] |

Leverstein-Van Hall MA, Blok HEM, Donders ART, et al. Multidrug resistance among enterobacteriaceae is strongly associated with the presence of integrons and is independent of species or isolate origin[J]. The Journal of Infectious Diseases, 2003, 187(2): 251-259. DOI:10.1086/jid.2003.187.issue-2 |

| [98] |

Xia WY, Xu T, Qin TT, et al. Characterization of integrons and novel cassette arrays in bacteria from clinical isloates in China, 2000-2014[J]. Journal of Biomedical Research, 2016, 30(4): 292-303. |

| [99] |

Turton JF, Kaufmann ME, Glover J, et al. Detection and typing of integrons in epidemic strains of Acinetobacter baumannii found in the United Kingdom[J]. Journal of Clinical Microbiology, 2005, 43(7): 3074-3082. |

| [100] |

Nardelli M, Marina Scalzo P, Soledad Ramirez M, et al. Class 1 integrons in environments with different degrees of urbanization[J]. PLoS One, 2012, 7(6): e392236. |

| [101] |

Borruso L, Harms K, Johnsen PJ, et al. Distribution of class 1 integrons in a highly impacted catchment[J]. Science of the Total Environment, 2016, 566-567: 1588-1594. DOI:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2016.06.054 |

| [102] |

Iversen A, Kühn I, Rahman M, et al. Evidence for transmission between humans and the environment of a nosocomial strain of Enterococcus faecium[J]. Environmental Microbiology, 2004, 6(1): 55-59. |

| [103] |

Hardwick SA, Stokes HW, Findlay S, et al. Quantification of class 1 integron abundance in natural environments using real-time quantitative PCR[J]. FEMS Microbiology Letters, 2008, 278(2): 207-212. |

| [104] |

Zhang XH, Xu YB, He XL, et al. Occurrence of antibiotic resistance genes in landfill leachate treatment plant and its effluent-receiving soil and surface water[J]. Environmental Pollution, 2016, 218: 1255-1261. |

| [105] |

Zhang XX, Zhang T, Fang HHP. Antibiotic resistance genes in water environment[J]. Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology, 2009, 82(3): 397-414. |

| [106] |

Patterson AJ, Colangeli R, Spigaglia P, et al. Distribution of specific tetracycline and erythromycin resistance genes in environmental samples assessed by macroarray detection[J]. Environmental Microbiology, 2007, 9(3): 703-715. |

| [107] |

Schmittgen TD, Lee EJ, Jiang JM. High-throughput real-time PCR[J]. Humana Press, 2008, 89-98. |

| [108] |

Williams MR, Stedtfeld RD, Waseem H, et al. Implications of direct amplification for measuring antimicrobial resistance using point-of-care devices[J]. Analytical Methods, 2017, 9(8): 1229-1241. |

| [109] |

Wright GD. The antibiotic resistome: the nexus of chemical and genetic diversity[J]. Nature Reviews Microbiology, 2007, 5(3): 175-186. DOI:10.1038/nrmicro1614 |

| [110] |

Surette MD, Wright GD. Lessons from the environmental antibiotic resistome[M]. Annual Review of Microbiology, 2017: 309-329.

|

| [111] |

Gibson MK, Forsberg KJ, Dantas G. Improved annotation of antibiotic resistance determinants reveals microbial resistomes cluster by ecology[J]. The ISME Journal, 2015, 9(1): 207-216. DOI:10.1038/ismej.2014.106 |

| [112] |

Martinez JL, Coque TM, Lanza VF, et al. Genomic and metagenomic technologies to explore the antibiotic resistance mobilome[J]. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 2017, 1388(1): 26-41. DOI:10.1111/nyas.2017.1388.issue-1 |

| [113] |

Sommer MOA, Dantas G, Church GM. Functional characterization of the antibiotic resistance reservoir in the human microflora[J]. Science, 2009, 325(5944): 1128-1131. DOI:10.1126/science.1176950 |

| [114] |

Riesenfeld CS, Goodman RM, Handelsman J. Uncultured soil bacteria are a reservoir of new antibiotic resistance genes[J]. Environmental Microbiology, 2004, 6(9): 981-989. |

| [115] |

Gillings MR, Paulsen IT, Tetu SG. Genomics and the evolution of antibiotic resistance[J]. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 2017, 1388(1): 92-107. DOI:10.1111/nyas.2017.1388.issue-1 |

| [116] |

Bakour S, Sankar SA, Rathored J, et al. Identification of virulence factors and antibiotic resistance markers using bacterial genomics[J]. Future Microbiology, 2016, 11(3): 455-466. DOI:10.2217/fmb.15.149 |

| [117] |

Xavier BB, Das AJ, Cochrane G, et al. Consolidating and exploring antibiotic resistance gene data resources[J]. Journal of Clinical Microbiology, 2016, 54(4): 851-859. |

| [118] |

Liu B, Pop M. ARDB-antibiotic resistance genes database[J]. Nucleic Acids Research, 2009, 37: D443-D447. DOI:10.1093/nar/gkn656 |

| [119] |

Yang Y, Li B, Zou SC, et al. Fate of antibiotic resistance genes in sewage treatment plant revealed by metagenomic approach[J]. Water Research, 2014, 62: 97-106. |

| [120] |

Moura A, Soares M, Pereira C, et al. INTEGRALL: a database and search engine for integrons, integrases and gene cassettes[J]. Bioinformatics, 2009, 25(8): 1096-1098. |

| [121] |

Cury J, Jové T, Touchon M, et al. Identification and analysis of integrons and cassette arrays in bacterial genomes[J]. Nucleic Acids Research, 2016, 44(10): 4539-4550. |

| [122] |

Amos GCA, Gozzard E, Carter CE, et al. Validated predictive modelling of the environmental resistome[J]. The ISME Journal, 2015, 9(6): 1467-1476. DOI:10.1038/ismej.2014.237 |

2018, Vol. 45

2018, Vol. 45