扩展功能

文章信息

- 谷涛, 李永丰, 张迹, 闫新, 蒋建东, 李顺鹏

- GU Tao, LI Yong-Feng, ZHANG Ji, YAN Xin, JIANG Jian-Dong, LI Shun-Peng

- 取代脲类除草剂的微生物降解

- Advances in microbial degradation of phenylurea herbicides

- 微生物学通报, 2017, 44(8): 1967-1979

- Microbiology China, 2017, 44(8): 1967-1979

- DOI: 10.13344/j.microbiol.china.160804

-

文章历史

- 收稿日期: 2016-11-06

- 接受日期: 2017-02-27

- 优先数字出版日期(www.cnki.net): 2017-03-23

2. 南京农业大学 农业部农业环境微生物工程重点开放实验室 江苏 南京 210095;

3. 淮阴师范学院 江苏省环洪泽湖生态农业生物技术重点实验室 江苏 淮安 223300

2. Key Laboratory of Microbiological Engineering Agricultural Environment, Ministry of Agriculture, College of Life Science, Nanjing Agricultural University, Nanjing, Jiangsu 210095, China;

3. Jiangsu Key Laboratory for Eco-Agricultural Biotechnology around Hongze Lake, School of Life Science, Huaiyin Normal University, Huai'an, Jiangsu 223300, China

取代脲类除草剂,核心结构由脲分子和苯环构成,是根据脲分子中氨基上取代基和苯环上取代基的不同而合成一系列除草剂(图 1),包括异丙隆、敌草隆、利谷隆、绿麦隆等多个品种。依据氨基上取代基(图 1B,d基团)的不同可将其分为两类:一类是N, N-二甲基取代脲类除草剂(图 1A),另一类是N-甲氧基-N-甲基取代脲类除草剂(图 1C)。同一类除草剂中,依据苯环上取代基的不同(图 1B,a和b基团)又可细分为不同的种类。此类除草剂主要作苗前土壤处理剂,防除一年生禾本科杂草和阔叶杂草,应用的作物有棉花、果树和谷物等。除草剂喷施后,药剂通过根部或者是叶部进入靶标植物中,阻断光系统Ⅱ中的电子传递,从而杀死杂草[1]。目前,取代脲类除草剂已成为全世界广泛使用的重要除草剂之一。

|

| 图 1 常用取代脲类除草剂分子结构式及取代脲类除草剂的核心结构 Figure 1 Chemical and core structures of some widely used phenylurea herbicides |

|

|

取代脲类除草剂具有较高的水溶性和较低的土壤吸附性,易被雨水或灌溉水从土壤中淋溶流失。因此,其在环境中的残留对水生生态系统有很大的风险。近年来,取代脲类除草剂的残留在全世界各个地区的地表水和地下水中不断被检测到,甚至在停用几年的国家和地区,残留仍然存在[2-3]。现有研究表明,取代脲类除草剂及其在环境中的代谢产物不仅对动植物和微生物有显著影响,而且对人类健康也造成了严重的威胁[4]。其在环境中残留的降解一直是研究的热点。

取代脲类除草剂化学性质稳定,非生物降解速度缓慢,但仍可以通过光解、水解、羟基化和氧化的作用进行微弱的降解[5]。环境中的取代脲类除草剂主要是通过生物作用被降解的,包括动物、植物和微生物的作用,其中微生物在整个过程中起着至关重要的作用,它们是降解作用的主力。到目前为止,已筛选得到大量的取代脲类除草剂降解菌株,阐明了此类除草剂的微生物代谢途径,克隆到了若干个降解基因,取得了一定的进展。

1 降解取代脲类除草剂的微生物通过微生物对取代脲类除草剂污染环境进行生物修复一直是世界各国环境工作者关注的重点。目前已经报道的降解取代脲类除草剂的微生物主要包括细菌和真菌。在这些降解微生物中,既有混合菌的培养液,也有单一的菌株。

1.1 混合培养液混合培养液中包含若干个菌株,它们联合起来行使降解功能,其中有的尚不清楚里面包含哪些菌株[6-8],有的组分明确[9-15]。在组分明确的混合培养液中,有些需所有菌株联合起来才能够矿化某种底物[11, 13],有些虽独自也可以降解,但是联合作用降解速度更快[9, 12, 15](表 1)。

| 年份 Year |

包含菌株 Strains |

降解底物 Substrates |

参考文献 References |

| 1993 | 一些革兰氏阳性菌和阴性菌 | 利谷隆、绿谷隆、绿溴隆、DCMU、DCU、3, 4-DCA | [6] |

| 2000 | 一些未知细菌 | 利谷隆、溴谷隆、3, 4-DCA、对溴苯胺 | [7] |

| 2001 | 一些未知细菌 | 异丙隆(IPU)、MDIPU、4IA | [8] |

| 2002 | 细菌SRS1和Sphingomonas sp. SRS2 | 异丙隆(增加降解速度) | [9] |

| 2003 | Variovorax sp. strain WDL1、Delftia acidovorans WDL34、Pseudomonas sp. strain WDL5、Hyphomicrobium sulfonivorans WDL6、Comamonas testosteroni WDL7 | 利谷隆、3, 4-DCA、N, O-DMHA | [10] |

| 2007 | Arthrobacter sp. N4和Delftia acidovorans sp. WDL34 | 敌草隆、3, 4-DCA | [11] |

| 2007 | Pseudomonas sp. IB78和Stenotrophomonas sp. IB93 | 敌草隆(增加降解速度) | [12] |

| 2008 | Variovorax sp. SRS16和Arthrobacter globiformis D47 | 敌草隆 | [13] |

| 2009 | Ancylobacter、Pseudomonas、Stenotrophomonas、Methylobacterium、Variovorax和Agrobacterium | 异丙隆、MDIPU、DDIPU、4IA | [14] |

| 2014 | Mortierella sp. LEJ702 (真菌)、Variovorax sp. SRS16 (细菌)、Arthrobacter globiformis D47 (细菌) | 敌草隆(增加降解速度) | [15] |

| 注:DCMU:1-(3, 4-二氯苯基)-3-甲基脲;DCU:N-(3, 4-二氯苯基)脲;3, 4-DCA:3, 4-二氯苯胺;N, O-DMHA:N, O-二甲基羟胺;IPU:异丙隆;MDIPU:1-(4-异丙基苯基)-3-甲基脲;DDIPU:1-对异丙基苯基脲;4IA:4-异丙基苯胺. Note: DCMU: N-(3, 4-dichlorophenyl)-N'-methylurea; DCU: N-(3, 4-dichlorophenyl)urea; 3, 4-DCA: 3, 4-dichloroaniline; N, O-DMHA: N, O-dimethylhydroxylamine; IPU: isoproturon; MDIPU: N-(4-isopropylphenyl)-N-methylurea; DDIPU: 1-(4-isopropylphenyl)urea; 4IA: 4-Isopropylaniline. | |||

在研究取代脲类除草剂降解之初,涉及的降解微生物大多是混合培养液,具有独立降解能力的菌株屈指可数。随着取代脲类除草剂残留问题的日益严重以及环境科学领域工作者的密切关注,取代脲类除草剂高效降解菌的报道日益增多。2001年,Sørensen等从连续使用取代脲类除草剂多年的农田土壤中分离得到一株降解菌Sphingomonas sp. SRS2,SRS2能完全矿化异丙隆,是第一株报道的能够独立矿化异丙隆的细菌,研究发现该菌还能够降解敌草隆和绿麦隆[16]。本实验室筛选分离得到的Sphingobium sp. YBL1、Sphingobium sp. YBL2、Sphingobium sp. YBL3和Sphingomonas sp. Y57都能够降解N, N-二甲基取代脲类除草剂异丙隆,其中Sphingobium sp. YBL1还能缓慢地降解利谷隆[17-18]。迄今为止,从世界各地分离获得了大量的取代脲类除草剂降解细菌(表 2)。从分离地区来看,主要集中在欧洲;从分类学来看,这些菌株主要分布在鞘氨醇杆菌属(Sphingobium)[17]、鞘氨醇单胞菌属(Sphingomonas)[16, 18-20]、贪噬菌属(Variovorax)[10, 13, 21-22]、节杆菌属(Arthrobacter)[23-25]、

| 分类(属) Genus |

降解菌株 Strains |

降解底物 Substrates |

地区 Region |

| 鞘氨醇杆菌属Sphingobium | Sphingobium sp. YBL1[17] | 异丙隆、利谷隆 | 中国 |

| Sphingobium sp. YBL2[17] | 异丙隆、敌草隆、绿麦隆、伏草隆 | 中国 | |

| Sphingobium sp. YBL3[17] | 异丙隆 | 中国 | |

| 鞘氨醇单胞菌属Sphingomonas | Sphingomonas sp. SRS2[16] | 异丙隆、敌草隆、绿麦隆 | 丹麦 |

| Sphingomonas sp. F35[19] | 异丙隆 | 英国 | |

| Sphingomonas sp. Y57[18] | 异丙隆、敌草隆、绿麦隆 | 中国 | |

| Sphingomonas sp. SH[20] | 异丙隆 | 法国 | |

| 贪噬菌属Variovorax | Variovorax sp. WDL1[10] | 利谷隆、溴谷隆 | 比利时 |

| Variovorax sp. PBL-H6[21] | 利谷隆 | 比利时 | |

| Variovorax sp. PBS-H4[21] | 利谷隆 | 比利时 | |

| Variovorax sp. SRS16[13] | 利谷隆、敌草隆(添加外源物质) | 丹麦 | |

| Variovorax sp. RA8[22] | 利谷隆、绿谷隆、溴谷隆、氯溴隆 | 日本 | |

| Variovorax sp. WDL1[10] | 利谷隆、溴谷隆 | 比利时 | |

| 节杆菌属Arthrobacter | Arthrobacter globiformis D47[23-24] | 敌草隆、利谷隆、绿谷隆、甲氧隆、异丙隆、绿麦隆、灭草隆 | 英国 |

| Arthrobacter sp. N2[25] | 敌草隆、绿麦隆、异丙隆 | 法国 | |

| 假单胞菌属Pseudomonas | Pseudomonas sp. Bk8[26] | 敌草隆 | 埃及 |

| Pseudomonas sp. IB78[12] | 敌草隆 | 法国 | |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa JS-11[27] | 异丙隆 | 沙特阿拉伯 | |

| 芽孢杆菌属Bacillis | Bacillis sphaericus ATCC 12123[28] | 利谷隆、绿谷隆、溴谷隆 | 德国 |

| Bacillus cereus ISL2[29] | 敌草隆 | 肯尼亚 | |

| Bacillus sp. ISL6[29] | 敌草隆 | 肯尼亚 | |

| 漫游球菌属Vogococcus | Vogococcus fluvialis ISL3[29] | 敌草隆 | 肯尼亚 |

| 伯克霍尔德菌属Burkholderia | Burkholderia ambifaria ISL4[29] | 敌草隆 | 肯尼亚 |

| 盐单胞菌属Stenotrophomona | Stenotrophomonas sp. IB93[12] | 敌草隆 | 法国 |

| 嗜甲基菌Methylopila | Methylopila sp. TES[30] | 异丙隆 | 法国 |

| 分支杆菌属Mycobacterium | Mycobacterium brisbanense JK1[31] | 敌草隆、异丙隆 | 澳大利亚 |

| 微球菌属Micrococcus | Micrococcus sp. PS-1[32] | 敌草隆、绿麦隆、灭草隆、非草隆、利谷隆、绿谷隆 | 印度 |

| 链霉菌属Streptomyces | Streptomyces sp. PS1/5[33] | 敌草隆、利谷隆 | 美国 |

假单胞菌属(Pseudomonas)[12, 26-27]和芽孢杆菌属(Bacillis)[28-29]。其中鞘氨醇杆菌属(Sphingobium)和鞘氨醇单胞菌属(Sphingomonas)的降解菌多与N, N-二甲基取代脲类除草剂(如异丙隆)的降解有关[16-20],而贪噬菌属的降解菌(Variovorax)则多与N-甲氧基-N-甲基取代脲类除草剂(如利谷隆)的降解有关[10, 13, 21-22]。近些年来筛选到的取代脲类除草剂的代表性降解菌株及其降解底物见表 2。

1.3 真菌真菌作为微生物的一个庞大类群,功能多样,其中大量菌株具有降解除草剂的能力。如早在1996年,Vroumsia等就测试了90株真菌对3种除草剂异丙隆、绿麦隆和敌草隆的降解性能,发现11%的测试菌株能够降解异丙隆,4%的供试菌株能够降解绿麦隆,7%的菌株能够降解敌草隆。在这些菌株中,Rhizoctonia solani的降解能力最强,能够同时降解这3种除草剂,5 d内对投加的异丙隆、敌草隆、绿麦隆的降解率达到了83%、97%和73%[34]。担子菌纲的一些菌种如Bjerkandera adusta在利用葡萄糖作为碳源时,两周能降解88%的异丙隆[35]。2005年,Rønhede等从农田土壤中分离约160多株真菌,并对10株属于Basidiomycetes、Ascomycetes和Zygomycetes的真菌做了进一步的研究,发现大多数菌株能够将异丙隆转化成其对应的脱甲基或羟基化产物[36]。其中,真菌Mortierella sp. Gr4能够降解多种取代脲类除草剂,包括异丙隆、敌草隆、利谷隆和绿麦隆[37]。

2 细菌降解取代脲类除草剂的主要途径在分离大量取代脲类除草剂降解菌株的同时,研究者对这类除草剂的降解途径也进行了深入的研究。由于取代脲类除草剂化学结构的相似性,导致这类除草剂的降解途径相似。研究发现,细菌降解取代脲类除草剂的主要途径有以下两种:(1) N, N-二甲基取代脲类除草剂经过连续的两步脱甲基后断裂脲桥,最后苯环开环。(2) N-甲氧基-N-甲基取代脲类除草剂直接断脲桥生成苯胺的衍生物,苯胺衍生物进一步被降解。

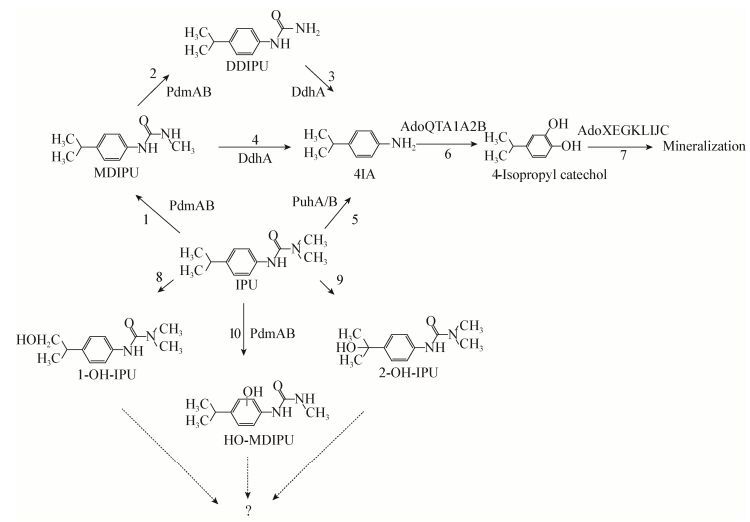

2.1 N, N-二甲基取代脲类除草剂的细菌降解途径N, N-二甲基取代脲类除草剂,核心结构氨基侧链上的取代基(图 1B,d基团)为-CH3,主要包括异丙隆、敌草隆、绿麦隆、灭草隆等多种除草剂。目前,对异丙隆和敌草隆的降解途径研究比较透彻,其它N, N-二甲基取代脲类除草剂因结构与这两种除草剂类似,代谢途径大同小异。研究表明,细菌降解异丙隆,首先是从N-上脱甲基生成MDIPU (图 2步骤1),该过程是降解的限速步骤[8, 17, 38]。本课题组在Sphingobium sp. YBL2降解异丙隆的过程中连续取样,代谢产物经高效液相色谱仪和质谱仪检测,并将其图谱与标准品的图谱对比,证实了降解过程中有DDIPU和4IA的生成,推测MDIPU能够进一步脱甲基生成了DDIPU,DDIPU的脲桥断裂后生成4IA (图 2步骤2-3)[38]。除了连续脱甲基以外,菌株Arthrobacter globiformis D47和菌株Arthrobacter globiformis N2能够直接将异丙隆的脲桥断裂生成4IA (图 2步骤5)[24-25],代谢产物MDIPU也能够直接断脲桥生成4IA (图 2步骤4)[8, 39],从YBL2菌株中克隆得到的基因ddhA,其表达产物能够将MDIPU催化成4IA,进一步验证了这一结果[39]。除了上述常见代谢产物外,Lehr等分离获得的细菌培养液在降解异丙隆时,会有异丙隆的羟基化产物1-OH-IPU和2-OH-IPU的生成(图 2步骤8-9)[40],但单菌能够将异丙隆降解成1-OH-IPU和2-OH-IPU未见报道。Sphingobium sp. YBL2降解异丙隆的过程中,通过高效液相色谱法和质谱法分析,发现代谢物中有MDIPU的羟基化产物(HO-MDIPU)的生成,且其羟基化位点不在异丙基侧链上,推测位于苯环上。因此,尝试利用制备液相色谱仪收集羟基化产物,但是由于羟基化产物与MDIPU分离困难、产物纯度达不到核磁共振的要求而告以失败。该羟基化位点具体位于苯环上的什么位置,仍需进一步的研究(图 2步骤10)[39]。1-OH-IPU、2-OH-IPU和HO-MDIPU能否进一步被细菌降解尚需研究。迄今为止,研究者已经对异丙隆的上游降解有了较清晰的认识,但对4IA和4IA下游产物的降解认识较少。4IA是苯胺衍生物,因此可在苯胺双加氧酶的作用下生成4-异丙基邻苯二酚(图 2步骤6),4-异丙基邻苯二酚通过邻苯二酚双加氧酶的作用进一步开环降解[17, 38-39](图 2步骤7)。

|

| 图 2 细菌降解N, N-二甲基取代脲类除草剂异丙隆的途径 Figure 2 Proposed metabolic pathways of isoproturon by bacterial strains 注:IPU:异丙隆[3-(4-异丙基苯基)-1, 1-二甲基脲];MDIPU:1-(4-异丙基苯基)-3-甲基脲;DDIPU:1-对异丙基苯基脲;4IA:4-异丙基苯胺;1-OH-IPU:3-(4-(2-羟基异丙基)苯)-1, 1-二甲基脲;2-OH-IPU:3-(4-(1-羟基异丙基)苯)-1, 1-二甲基脲. Note: IPU: Isoproturon(3-(4-isopropylphenyl)-1, 1-dimethylurea); MDIPU: N-(4-isopropylphenyl)-N-methylurea; DDIPU: 1-(4-isopropylphenyl) urea; 4IA: 4-Isopropylaniline; 1-OH-IPU: N-(4-(2-hydroxy-1-methylethyl)phenyl)-N', N'-dimethylurea; 2-OH-IPU: N-(4-(1-hydroxy-1-methylethyl)phenyl)-N', N'-dimethylurea. |

|

|

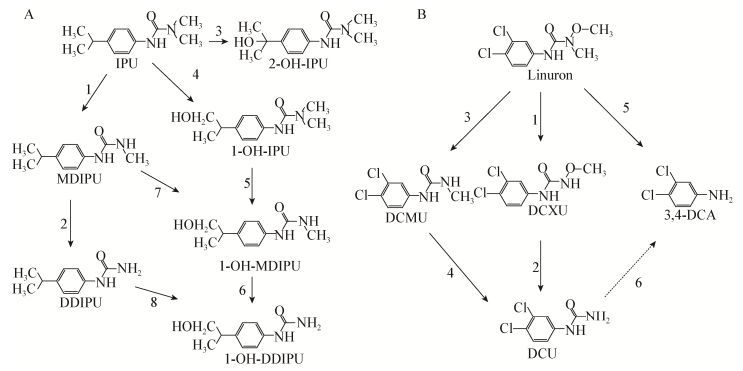

敌草隆与异丙隆的代谢途径初始步骤相同,两步脱甲基后脲桥断裂生成3, 4-DCA。如细菌Sphingomonas sp. SRS2能够将敌草隆脱甲基生成DCMU,DCMU可以进一步脱甲基生成DCU,DCU断脲桥生成3, 4-DCA (图 3,步骤1-3)[41]。Micrococcus sp. PS降解敌草隆的过程中,敌草隆先脱一个甲基生成DCMU,DCMU不需要经过再一次的脱甲基,被直接降解成3, 4-DCA[32](图 3步骤4)。与异丙隆相同,敌草隆也可以直接断脲桥生成3, 4-DCA (图 3步骤5)。如菌株Arthrobacter globiformis D47、Arthrobacter sp. N2、Mycobacteriumbrisbanense JK1和Pseudomonas sp. Bk8均能直接断脲桥降解敌草隆[24-26, 31]。细菌降解3, 4-DCA主要通过脱卤作用、羟基化作用和氧化脱氨基作用等。Sharma等在研究Micrococcus sp. PS-1降解敌草隆时,发现产物中有DCB、4, 5-DBD和3-COHDA生成,表明3, 4-DCA首先脱氨基生成DCB (图 3步骤6),DCB进一步被氧化成4, 5-DBD (图 3步骤10),4, 5-DBD可能转化为3, 4-DCHD,而后被进一步降解为3-COHDA (图 3步骤11-12),最后完全矿化[32]。菌株Acinetobacter baylyi GFJ2能将3, 4-DCA脱氯生成4-氯苯胺(图 3步骤7)。4-氯苯胺存在两条降解途径,一条是氧化脱氨基生成4-氯邻苯二酚(图 3步骤14),另一条途径是再次脱氯生成苯胺(图 3步骤13),苯胺在苯胺加氧酶的催化下变成邻苯二酚(图 3步骤16)。4-氯邻苯二酚和邻苯二酚最终开环降解(图 3步骤15和17)[42]。另外,Pseudomonas fluorescens 26-K在降解3, 4-DCA时,除了发现有3-氯-4-羟基苯胺生成以外,还发现有微量的N-(3, 4-二氯苯基)乙酰胺和双(3, 4-二氯苯基)二氮烯-1-氧化物生成,说明细菌可以通过酰基化或者耦合作用转化3, 4-DCA (图 3步骤8-9)[43]。

|

| 图 3 细菌降解敌草隆和利谷隆的途径 Figure 3 Proposed degradation pathways of diuron and linuron by bacterial strains 注:DCMU:1-(3, 4-二氯苯基)-3-甲基脲;DCU:N-(3, 4-二氯苯基)脲;3, 4-DCA:3, 4-二氯苯胺;1, 2-DCB:1, 2-二氯苯;4, 5-DCC:4, 5-二氯邻苯二酚;3, 4-DCHD:1, 6-二羟基-3, 4-二氯-3-己烯;3-COHDA:3-氯-4-酮己二酸. Note: DCMU: N-(3, 4-dichlorophenyl)-N'-methylurea; DCU: N-(3, 4-dichlorophenyl)urea; 3, 4-DCA: 3, 4-dichloroaniline; 1, 2-DCB: 1, 2-dichlorobenzene; 4, 5-DCC: 4, 5-dichlorocatechol; 3, 4-DCHD: 3, 4-dichlorohex-3-ene-1, 6-diol; 3-COHDA: 3-chloro-4-oxohexane dioic acid. |

|

|

利谷隆、绿谷隆、溴谷隆和氯溴隆等属于N-甲氧基-N-甲基取代脲类除草剂。利谷隆是此类除草剂的代表,研究报道较多。利谷隆在降解的时候,主要是脲桥首先受到攻击,断裂生成3, 4-二氯苯胺(3, 4-DCA)和N, O-二甲基羟胺(图 3)。Dejonghe等在用Variovorax sp. WDL1降解利谷隆时发现有3, 4-DCA的积累,说明利谷隆是直接断脲桥生成3, 4-DCA[10]。Variovorax sp. SRS16也是一株高效利谷隆降解菌,该菌降解利谷隆途径与Variovorax sp. WDL1相同,利谷隆被直接降解成3, 4-DCA,中间代谢产物3, 4-DCA被进一步转化成4, 5-二氯邻苯二酚,并最终进入TCA循环。N, O-二甲基羟胺被降解成CO2和H2O[44](图 3)。到目前为止,通过脱甲基或者脱甲氧基来降解利谷隆的细菌还未见报道。

3 真菌降解取代脲类除草剂的途径真菌能够降解取代脲类除草剂,且代谢途径较细菌复杂。在真菌的作用下,异丙隆(IPU)被羟基化生成1-OH-IPU和2-OH-IPU[36](图 4A步骤3和4),羟基化后的产物在土壤中的降解速度比异丙隆和MDIPU快,说明异丙隆的羟基化是环境中异丙隆矿化的关键途径[45]。如真菌Mortierella sp. Gr4、Phomacf eupyrena Gr61和Alternaria sp. Gr174都能将异丙隆羟基化,其羟基化的位点为异丙基侧链的第一位,生成了1-OH-IPU (图 4A步骤4),而菌株Mucor sp. strain Gr22能够在异丙基侧链的第二位上羟基化,生成2-OH-IPU (图 4A步骤3)。一个担子菌纲(Basidiomycete)的真菌Gr177降解异丙隆时,除了有上述两种羟基化产物的生成以外,还有脱甲基产物的产生。Clonostachys sp. Gr141和Tetracladium sp. Gr57能将IPU脱甲基成MDIPU,但不能羟基化IPU[36](图 4A步骤1)。Badawi等进一步研究发现Mortierella sp. Gr能够同时将IPU脱甲基和羟基化,生成的产物中既有脱甲基的产物MDIPU和DDIPU,又有羟基化产物1-OH-IPU、1-OH-MDIPU和1-OH-DDIPU,因此推测生成的1-OH-IPU可以连续脱甲基生成1-OH-MDIPU和1-OH-DDIPU,脱甲基产物MDIPU和DDIPU也可以被羟基化成对应羟基化产物,形成一个网络状的降解途径[37](图 4A步骤1-2和4-8)。

|

| 图 4 真菌降解异丙隆和利谷隆的途径 Figure 4 Fungal degradation pathways of isoproturon and linuron 注:IPU:异丙隆(3-(4-异丙基苯基)-1, 1-二甲基脲);MDIPU:1-(4-异丙基苯基)-3-甲基脲;DDIPU:1-对异丙基苯基脲;1-OH-IPU:3-(4-(2-羟基异丙基)苯)-1, 1-二甲基脲;2-OH-IPU:3-(4-(1-羟基异丙基)苯)-1, 1-二甲基脲;1-OH-MDIPU:3-(4-(2-羟基异丙基)苯)-1-甲基脲;1-OH-DDIPU:3-(4-(2-羟基异丙基)苯基脲;DCMU:1-(3, 4-二氯苯基)-3-甲基脲;DCXU:1-(3, 4-二氯苯基)-3-甲氧基脲;DCU:N-(3, 4-二氯苯基)脲;3, 4-DCA:3, 4-二氯苯胺. Note: IPU: isoproturon(3-(4-isopropylphenyl)-1, 1-dimethylurea); MDIPU: N-(4-isopropylphenyl)-N-methylurea; DDIPU: 1-(4-isopropylphenyl) urea; 1-OH-IPU: N-(4-(2-hydroxy-1-methylethyl)phenyl)-N', N'-dimethylurea; 2-OH-IPU: N-(4-(1-hydroxy-1-methylethyl)phenyl)-N', N'-dimethylurea; 1-OH-MDIPU: N-(4-(2-hydroxy-1-methylethyl)phenyl)-N'-dimethylurea; 1-OH-DDIPU: N-(4-(2-hydroxy-1-methylethyl)phenyl) urea; DCMU: N-(3, 4-dichlorophenyl)-N'-methylurea; DCXU: N-(3, 4-dichlorophenyl)-N'-methoxyurea; DCU: N-(3, 4-dichlorophenyl)urea; 3, 4-DCA: 3, 4-dichloroaniline. |

|

|

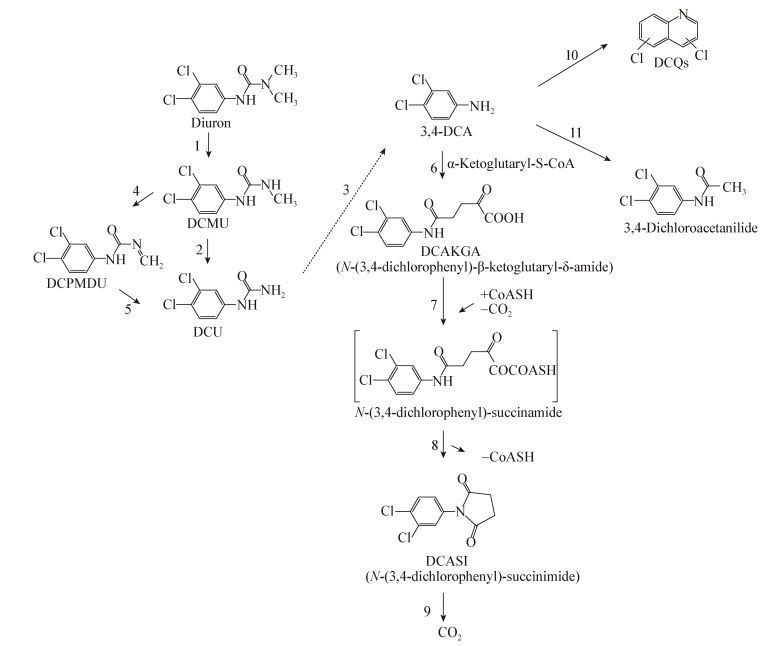

Mortierella sp. Gr4降解底物谱较广,除了异丙隆,它还能降解绿麦隆、敌草隆和利谷隆。Gr4降解利谷隆是先脱甲基生成DCXU,然后DCXU再脱甲氧基生成DCU (图 4B步骤1-2),也可以先脱甲氧基生成DCMU,DCMU再脱甲基成DCU (图 4B步骤3-4)。另外,在降解利谷隆的过程中,出现的第一个产物是3, 4-DCA,因此推测利谷隆可以直接被水解为3, 4-DCA[37](图 4B步骤5)。真菌能否将DCU水解为3, 4-DCA有待进一步的研究(图 4B步骤6)。

真菌降解敌草隆的途径与细菌有相似之处,也有区别。相同之处是都有脱甲基产物生成(图 5,步骤1-2)。如Mortierella sp. Gr4降解敌草隆过程中有DCMU和DCU的生成[37]。主要区别是真菌降解过程中出现了一个新代谢产物DCPMDU,推测DCMU是经过DCPMDU被催化成DCU[46](图 5步骤4-5)。另外,真菌降解3, 4-DCA的途径与细菌也有差异。如Sandermann等研究发现真菌Phanerochaete chrysosporium ATCC34541在某种条件下能够将3, 4-DCA转化成DCAKGA,而后进一步转化成DCASI后被矿化(图 5步骤6-9)[47]。3, 4-DCA在真菌的作用下,还可以被转化成3, 4-二氯乙酰苯胺和二氯喹啉(DCQs)等产物(图 5步骤10-11)[48-49]。环境中的取代脲类除草剂在真菌和细菌的联合作用下代谢降解。

|

| 图 5 真菌降解敌草隆和3, 4-DCA的途径 Figure 5 Fungal degradation pathways of diuron and 3, 4-DCA 注:DCMU:1-(3, 4-二氯苯基)-3-甲基脲;DCU:N-(3, 4-二氯苯基)脲;DCAKGA:N-(3, 4-二氯苯基)-α-酮戊二酸-δ-酰胺;DCASI:N-(3, 4-二氯苯基)-琥珀酰亚胺. Note: DCMU: N-(3, 4-dichlorophenyl)-N'-methylurea; DCU: N-(3, 4-dichlorophenyl)urea; DCAKGA: N-(3, 4-dichlorophenyl)-α-ketoglutaryl-δ-amide; DCASI: N-(3, 4-dichlorophenyl)-succinimide. |

|

|

在取代脲类除草剂降解有关的基因和酶方面的研究也取得了较大进展(表 3)。Engelhardt等从菌株Bacillus sphaericus ATCC 12123中纯化出一个75 kD的芳基酰胺酶,该酶能切断利谷隆等N-甲氧基-N-甲基苯基脲类除草剂的脲桥,但是不能作用于异丙隆、敌草隆等N, N-二甲类苯基脲除草剂的脲桥,也没克隆到相关的基因[50];克隆自Arthrobacter globiformis D47和Mycobacterium brisbanense JK1中的水解酶基因puhA和puhB具有较高的相似性,它们编码的酶可以切断大多数苯基脲类除草剂的脲桥,但它们对N, N-二甲基取代脲类除草剂的催化活性较低[31, 51](图 2、3)。Breugelmans等研究WDL1降解利谷隆和3, 4-DCA时,发现3, 4-DCA的降解与苯胺双加氧酶密切相关[52]。Bers等从菌株SRS16中分离纯化了利谷隆水解酶LibA,其研究表明LibA是一个大小约为55 kD的单体蛋白,能够直接断开利谷隆结构中的脲桥生成3, 4-二氯苯胺,不能作用于其他的取代脲类除草剂。同时他们还通过基因组测序的方法获得了该酶基因libA,以及与开环降解有关的基因簇dcaQTA1A2BR和ccdRCFDE,其中dca为二氯苯胺多组分双加氧酶基因簇,负责3, 4-二氯苯胺加氧脱氨,而ccd则是邻苯二酚邻位开环途径基因簇,负责进一步开环降解苯环结构,使除草剂彻底被矿化[53](图 3)。2013年,Bers等又从利谷隆的降解菌株Variovorax sp. WDL1中克隆到一个水解酶基因hylA,HylA能够将利谷隆催化为3, 4-DCA,该酶与已报道的LibA不同,属于不同家族的蛋白[44]。同年,作者利用转座子随机插入突变的方法,从降解菌株YBL2中克隆到一个脱甲基酶基因pdmAB,该基因编码蛋白能够使异丙隆脱一个甲基生成MDIPU,同时它还能催化敌草隆、绿麦隆、甲氧隆等N, N-二甲基取代脲类除草剂的脱甲基,进一步研究发现PdmAB还能从MDIPU上脱甲基生成DDIPU,但速度较慢[39, 54](图 3)。最近,本实验室又从YBL2中克隆到了负责切断DDIPU脲桥的基因ddhA、苯胺双加氧酶基因簇adoQTA1A2B以及邻苯二酚开环基因簇adoXEGKLIJC,这也是目前取代脲类除草剂降解基因相关研究的最新进展(图 2)[39]。

| 酶或基因(簇)名称 Name |

大小 Size (bp/kD) |

来源 Organism |

功能(底物) Function (substrates) |

| 芳基酰胺酶[50] Aryl acylamidase | 75 kD | Bacillus sphaericus ATCC 12123 | 断脲桥(N-甲氧基-N-甲基-) |

| puhA[51] | 1 368 bp | Arthrobacter globiformis D47 | 断脲桥(大多数取代脲类除草剂) |

| puhB[31] | 1 386 bp | Mycobacterium brisbanense JK1 | 断脲桥(大多数取代脲类除草剂) |

| LibA/libA[53] | 55 kD/1 428 bp | Variovorax sp. strain SRS16 | 断脲桥(利谷隆) |

| dcaQTA1A2BR[53] | - | Variovorax sp. strain SRS16 | 二氯苯胺加氧脱氨(3, 4-DCA) |

| ccdRCFDE[53] | - | Variovorax sp. strain SRS16 | 苯环开环降解(邻苯二酚) |

| hylA[44] | 1 755 bp | Variovorax sp. WDL1 | 断脲桥(利谷隆) |

| pdmAB[54] | 1 907 bp | Sphingobium sp. YBL2 | 脱甲基(N, N-二甲基-) |

| ddhA[39] | 2 139 bp | Sphingobium sp. YBL2 | 断脲桥(MDIPU和DDIPU) |

| adoQTA1A2B[39] | - | Sphingobium sp. YBL2 | 二氯苯胺加氧脱氨(3, 4-DCA) |

| adoXEGKLIJC[39] | - | Sphingobium sp. YBL2 | 苯环开环降解(邻苯二酚) |

从取代脲类除草剂开始使用到现在,此类除草剂及其代谢产物在环境中的残留、降解就备受关注。微生物中的细菌和真菌数量庞大、种类繁多,在除草剂的降解过程中起着重要的作用,而通过微生物对污染环境进行生物修复是一种高效、安全、成本低、无二次污染的技术,具有广阔的发展前景[55]。迄今为止,已报道的取代脲类除草剂的降解菌(细菌)有数十株(表 2),但大多数菌株并不理想,要么是降解速度缓慢,要么是底物谱较窄。因此,筛选高效、广谱、适应能力强的菌株资源是一项必要且需长期坚持的工作。真菌降解菌株在降解速度和底物谱方面不比细菌弱[37],在今后的工作中要加大真菌降解菌株的筛选工作。真菌的降解途径与细菌差异明显,存在互补现象,将两种微生物联合利用或许可以获得更好的降解效果。除了筛选降解菌株以外,研究者对细菌和真菌降解取代脲类除草剂的途径也进行了研究,结果表明细菌降解取代脲类除草剂主要包含两条途径:N, N-二甲基取代脲类除草剂主要通过连续两步脱甲基作用后断脲桥降解,而N-甲氧基-N-甲基苯基脲类除草剂通过直接断脲桥降解。真菌降解取代脲类除草剂的途径更加丰富多样,但尚未完全阐明,此方面研究亟待加强。

经过几十年的不懈努力,研究人员已经从细菌中克隆到了若干个负责取代脲类除草剂降解的基因,其中较有代表性的关键基因有puhA、puhB、libA、hylA、pdmAB和ddhA。本课题组从菌株Sphingobium sp. YBL2中克隆到了两个关键酶基因pdmAB和ddhA,这一成果填补了N, N-二甲基取代脲类除草剂降解途径中无基因克隆的空白,解析了异丙隆等N, N-二甲基取代脲类除草剂降解的分子机理。同时,笔者发现基因pdmAB和ddhA在异丙隆降解菌株Sphingobiumssp. YBL1、YBL2、YBL3和Sphingomonas ssp. SRS2、Y57中高度保守,预示这两个基因可通过水平转移的方式转移[54]。除草剂降解基因的克隆有助于了解微生物降解有毒、有害化合物的过程,从而推动其污染环境的生物修复工作。另外,在市场化的抗除草剂转基因作物中,许多抗性基因来源于微生物[56],因此在转基因作物方面,除草剂降解基因也有很大的应用空间。目前,杂草的抗药性日趋严重,推荐剂量下的除草剂已很难控制抗性杂草,施用高剂量的除草剂虽能有效防控杂草,但对作物产生了一定的药害,间接影响了作物的产量,抗除草剂转基因作物的出现,一定意义上解决了这一问题。研究表明异丙隆脱甲基产物的植物毒性显著降低且更易降解[57],因此pdmAB被转化到模式植物拟南芥中,结果显示转基因拟南芥对异丙隆的抗药性显著提高,pdmAB有望在转基因作物领域大显身手。尽管在取代脲类微生物降解方面已经取得了一定的研究进展,但将相关菌株应用于污染环境生物修复,还有很长的路要走。此外,真菌中是哪些基因负责降解?降解酶的催化机理如何?相信这些问题将随着研究的逐步深入和新技术的应用,通过比较基因组学、转录组学、蛋白组学和蛋白晶体解析等手段得以进一步的解决。

| [1] |

Pascal-Lorber S, Alsayeda H, Jouanin I, et al. [1] Pascal-Lorber S, Alsayeda H, Jouanin I, et al. Metabolic fate of [14C] diuron and [14C] linuron in wheat (Triticum aestivum) and radish (Raphanus sativus)[J]. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry, 2010, 58(20): 10935-10944[J]. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry, 2010, 58(20): 10935-10944. DOI:10.1021/jf101937x |

| [2] |

Abbot J, Marohasy J. Has the herbicide diuron caused mangrove dieback? A re-examination of the evidence[J]. Human and Ecological Risk Assessment: An International Journal, 2011, 17(5): 1077-1094. DOI:10.1080/10807039.2011.605672 |

| [3] |

Johnson AC, Besien TJ, Bhardwaj CL, et al. Penetration of herbicides to groundwater in an unconfined chalk aquifer following normal soil applications[J]. Journal of Contaminant Hydrology, 2001, 53(1/2): 101-117. |

| [4] |

Da Rocha MS, Arnold LL, Dodmane PR, et al. Diuron metabolites and urothelial cytotoxicity: in vivo, in vitro and molecular approaches[J]. Toxicology, 2013, 314(2/3): 238-246. |

| [5] |

Hussain S, Arshad M, Springael D, et al. Abiotic and biotic processes governing the fate of phenylurea herbicides in soils: a review[J]. Critical Reviews in Environmental Science and Technology, 2015, 45(18): 1947-1998. DOI:10.1080/10643389.2014.1001141 |

| [6] |

Roberts SJ, Walker A, Parekh NR, et al. Studies on a mixed bacterial culture from soil which degrades the herbicide Linuron[J]. Pest Management Science, 1993, 39(1): 71-78. DOI:10.1002/ps.v39:1 |

| [7] |

El-Fantroussi S. Enrichment and molecular characterization of a bacterial culture that degrades methoxy-methyl urea herbicides and their aniline derivatives[J]. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 2000, 66(12): 5110-5115. DOI:10.1128/AEM.66.12.5110-5115.2000 |

| [8] |

Sørensen SR, Aamand J. Biodegradation of the phenylurea herbicide isoproturon and its metabolites in agricultural soils[J]. Biodegradation, 2001, 12(1): 69-77. DOI:10.1023/A:1011902012131 |

| [9] |

Sørensen SR, Ronen Z, Aamand J. Growth in coculture stimulates metabolism of the phenylurea herbicide isoproturon by Sphingomonas sp. strain SRS2[J]. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 2002, 68(7): 3478-3485. DOI:10.1128/AEM.68.7.3478-3485.2002 |

| [10] |

Dejonghe W, Berteloot E, Goris J, et al. Synergistic degradation of linuron by a bacterial consortium and isolation of a single linuron-degrading Variovorax strain[J]. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 2003, 69(3): 1532-1541. DOI:10.1128/AEM.69.3.1532-1541.2003 |

| [11] |

Bazot S, Bois P, Joyeux C, et al. Mineralization of diuron [3-(3, 4-dichlorophenyl)-1, 1-dimethylurea] by co-immobilized Arthrobacter sp. and Delftia acidovorans[J]. Biotechnology Letters, 2007, 29(5): 749-754. DOI:10.1007/s10529-007-9316-7 |

| [12] |

Batisson I, Pesce S, Besse-Hoggan P, et al. Isolation and characterization of diuron-degrading bacteria from lotic surface water[J]. Microbial Ecology, 2007, 54(4): 761-770. DOI:10.1007/s00248-007-9241-2 |

| [13] |

Sørensen SR, Albers CN, Aamand J. Aamand J. Rapid mineralization of the phenylurea herbicide diuron by Variovorax sp. strain SRS16 in pure culture and within a two-member consortium[J]. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 2008, 74(8): 2332-2340. DOI:10.1128/AEM.02687-07 |

| [14] |

Hussain S, Sørensen SR, Devers-Lamrani M, et al. Characterization of an isoproturon mineralizing bacterial culture enriched from a French agricultural soil[J]. Chemosphere, 2009, 77(8): 1052-1059. DOI:10.1016/j.chemosphere.2009.09.020 |

| [15] |

Ellegaard-Jensen L, Knudsen BE, Johansen A, et al. Fungal-bacterial consortia increase diuron degradation in water-unsaturated systems[J]. Science of the Total Environment, 2014, 466-467: 699-705. DOI:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2013.07.095 |

| [16] |

Sørensen SR, Ronen Z, Aamand J. Isolation from agricultural soil and characterization of a Sphingomonas sp. able to mineralize the phenylurea herbicide isoproturon[J]. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 2001, 67(12): 5403-5409. DOI:10.1128/AEM.67.12.5403-5409.2001 |

| [17] |

Sun JQ, Huang X, Chen QL, et al. Isolation and characterization of three Sphingobium sp. strains capable of degrading isoproturon and cloning of the catechol 1, 2-dioxygenase gene from these strains[J]. World Journal of Microbiology and Biotechnology, 2009, 25(2): 259-268. DOI:10.1007/s11274-008-9888-y |

| [18] |

Sun JQ, Huang X, He J, et al. Isolation identification of isoproturon degradation bacterium Y57 and its degradation characteristic[J]. China Environmental Science, 2006, 26(3): 315-319. (in Chinese) 孙纪全, 黄星, 何健, 等. 异丙隆降解菌Y57的分离鉴定及其降解特性[J]. 中国环境科学, 2006, 26(3): 315-319. |

| [19] |

Bending GD, Lincoln SD, Sørensen SR, et al. In-field spatial variability in the degradation of the phenyl-urea herbicide isoproturon is the result of interactions between degradative Sphingomonas spp. and soil pH[J]. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 2003, 69(2): 827-834. DOI:10.1128/AEM.69.2.827-834.2003 |

| [20] |

Hussain S, Devers-Lamrani M, El AN, et al. Isolation and characterization of an isoproturon mineralizing Sphingomonas sp. strain SH from a French agricultural soil[J]. Biodegradation, 2011, 22(3): 637-650. DOI:10.1007/s10532-010-9437-x |

| [21] |

Breugelmans P, D'Huys PJ, de Mot R, et al. Characterization of novel linuron-mineralizing bacterial consortia enriched from long-term linuron-treated agricultural soils[J]. FEMS Microbiology Ecology, 2008, 62(3): 374-385. |

| [22] |

Satsuma K. Mineralisation of the herbicide linuron by Variovorax sp. strain RA8 isolated from Japanese river sediment using an ecosystem model (microcosm)[J]. Pest Management Science, 2010, 66(8): 847-852. |

| [23] |

Cullington JE, Walker A. Rapid biodegradation of diuron and other phenylurea herbicides by a soil bacterium[J]. Soil Biology and Biochemistry, 1999, 31(5): 677-686. DOI:10.1016/S0038-0717(98)00156-4 |

| [24] |

Turnbull G, Cullington J, Walker A, et al. Identification and characterisation of a diuron-degrading bacterium[J]. Biology and Fertility of Soils, 2001, 33(6): 472-476. DOI:10.1007/s003740100353 |

| [25] |

Tixier C, Sancelme M, A t-A ssa S, et al. Biotransformation of phenylurea herbicides by a soil bacterial strain, Arthrobacter sp. N2: structure, ecotoxicity and fate of diuron metabolite with soil fungi[J]. Chemosphere, 2002, 46(4): 519-526. DOI:10.1016/S0045-6535(01)00193-X |

| [26] |

El-Deeb BA, Soltan SM, Ali AM, et al. Detoxication of the herbicide diuron by Pseudomonas sp.[J]. Folia Microbiologica, 2000, 45(3): 211-216. DOI:10.1007/BF02908946 |

| [27] |

Dwivedi S, Singh BR, Al-Khedhairy AA, et al. Biodegradation of isoproturon using a novel Pseudomonas aeruginosa, strain JS-11 as a multi-functional bioinoculant of environmental significance[J]. Journal of Hazardous Materials, 2011, 185(2/3): 938-944. |

| [28] |

Walln fer P. The decomposition of urea herbicides by Bacillus sphaericus, isolated from soil[J]. Weed Research, 1969, 9(4): 333-339. DOI:10.1111/wre.1969.9.issue-4 |

| [29] |

Ngigi A, Getenga Z, Ndalut HBP. Biodegradation of phenylurea herbicide diuron by microorganisms from long-term-treated sugarcane-cultivated soils in Kenya[J]. Toxicological & Environmental Chemistry, 2011, 93(8): 1623-1635. |

| [30] |

Sebai TE, Lagacherie B, Soulas G, et al. Isolation and characterisation of an isoproturon-mineralising Methylopila sp. TES from French agricultural soil[J]. FEMS Microbiology Letters, 2004, 239(1): 103-110. DOI:10.1016/j.femsle.2004.08.017 |

| [31] |

Khurana JL, Jackson CJ, Scott C, et al. Characterization of the phenylurea hydrolases A and B: founding members of a novel amidohydrolase subgroup[J]. Biochemical Journal, 2009, 418(2): 431-441. DOI:10.1042/BJ20081488 |

| [32] |

Sharma P, Chopra A, Cameotra SS, et al. Efficient biotransformation of herbicide diuron by bacterial strain Micrococcus sp. PS-1[J]. Biodegradation, 2010, 21(6): 979-987. DOI:10.1007/s10532-010-9357-9 |

| [33] |

Shelton DR, Khader S, Karns JS, et al. Metabolism of twelve herbicides by Streptomyces[J]. Biodegradation, 1996, 7(2): 129-136. DOI:10.1007/BF00114625 |

| [34] |

Vroumsia T, Steiman R, Seigle-Murandi F, et al. Biodegradation of three substituted phenylurea herbicides (chlortoluron, diuron, and isoproturon) by soil fungi. A comparative study[J]. Chemosphere, 1996, 33(10): 2045-2056. DOI:10.1016/0045-6535(96)00318-9 |

| [35] |

Khadrani A, Seigle-Murandi F, Steiman R, et al. Degradation of three phenylurea herbicides (chlortoluron, isoproturon and diuron) by micromycetes isolated from soil[J]. Chemosphere, 1999, 38(13): 3041-3050. DOI:10.1016/S0045-6535(98)00510-4 |

| [36] |

Rønhede S, Jensen B, Rosendahl S, et al. Hydroxylation of the herbicide isoproturon by fungi isolated from agricultural soil[J]. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 2005, 71(12): 7927-7932. DOI:10.1128/AEM.71.12.7927-7932.2005 |

| [37] |

Badawi N, Rønhede S, Olsson S, et al. Metabolites of the phenylurea herbicides chlorotoluron, diuron, isoproturon and linuron produced by the soil fungus Mortierella sp.[J]. Environmental Pollution, 2009, 157(10): 2806-2812. DOI:10.1016/j.envpol.2009.04.019 |

| [38] |

Zhang J, Hong Q, Li QF, et al. Characterization of isoproturon biodegradation pathway in Sphingobium sp. YBL2[J]. International Biodeterioration & Biodegradation, 2012, 70: 8-13. |

| [39] |

Yan X, Gu T, Yi ZQ, et al. Comparative genomic analysis of isoproturon-mineralizing sphingomonads reveals the isoproturon catabolic mechanism[J]. Environmental Microbiology, 2016, 18: 4888-4906. DOI:10.1111/1462-2920.13413 |

| [40] |

Lehr S, Gl gen WE, Sandermann, et al. Metabolism of isoproturon in soils originating from different agricultural management systems and in cultures of isolated soil bacteria[J]. International Journal of Environmental Analytical Chemistry, 1996, 65(1/4): 231-243. |

| [41] |

Sørensen SR, Juhler RK, Aamand J. Degradation and mineralisation of diuron by Sphingomonas sp. SRS2 and its potential for remediating at a realistic μg L(-1) diuron concentration[J]. Pest Management Science, 2013, 69(11): 1239-1244. |

| [42] |

Hongsawat P, Vangnai AS. Biodegradation pathways of chloroanilines by Acinetobacter baylyi strain GFJ2[J]. Journal of Hazardous Materials, 2011, 186(2/3): 1300-1307. |

| [43] |

Travkin VVM, Solyanikova IIP, Rietjens IIMCM, et al. Degradation of 3, 4-dichloro-and 3, 4-difluoroaniline by Pseudomonas fluorescens 26-K[J]. Journal of Environmental Science & Health, Part B: Pesticides, Food Contaminants, and Agricultural Wastes, 2003, 38(2): 121-132. |

| [44] |

Bers K, Batisson I, Proost P, et al. HylA, an alternative hydrolase for initiation of catabolism of the phenylurea herbicide linuron in Variovorax sp. strains[J]. HylA, an alternative hydrolase for initiation of catabolism of the phenylurea herbicide linuron in Variovorax sp. strains, 2013, 79(17): 5258-5263. |

| [45] |

Rønhede S, Sørensen SR, Jensen B, et al. Mineralization of hydroxylated isoproturon metabolites produced by fungi[J]. Soil Biology and Biochemistry, 2007, 39(7): 1751-1758. DOI:10.1016/j.soilbio.2007.01.037 |

| [46] |

Ellegaard-Jensen L, Aamand J, Kragelund BB, et al. Strains of the soil fungus Mortierella show different degradation potentials for the phenylurea herbicide diuron[J]. Biodegradation, 2013, 24(6): 765-774. DOI:10.1007/s10532-013-9624-7 |

| [47] |

Sandermann H Jr, Heller W, Hertkorn N, et al. A new intermediate in the mineralization of 3, 4-dichloroaniline by the white rot fungus Phanerochaete chrysosporium[J]. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 1998, 64(9): 3305-3312. |

| [48] |

Giacomazzi S, Cochet N. Environmental impact of diuron transformation: a review[J]. Chemosphere, 2004, 56(11): 1021-1032. DOI:10.1016/j.chemosphere.2004.04.061 |

| [49] |

Castillo JM, Nogales R, Romero E. Biodegradation of 3, 4 dichloroaniline by fungal isolated from the preconditioning phase of winery wastes subjected to vermicomposting[J]. Journal of Hazardous Materials, 2014, 267: 119-127. DOI:10.1016/j.jhazmat.2013.12.052 |

| [50] |

Engelhardt G, Walln fer PR, Plapp R. Purification and properties of an aryl acylamidase of Bacillus sphaericus, catalyzing the hydrolysis of various phenylamide herbicides and fungicides[J]. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 1973, 26(5): 709-718. |

| [51] |

Turnbull GA, Ousley M, Walker A, et al. Degradation of substituted phenylurea herbicides by Arthrobacter globiformis strain D47 and characterization of a plasmid-associated hydrolase gene, puhA[J]. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 2001, 67(5): 2270-2275. DOI:10.1128/AEM.67.5.2270-2275.2001 |

| [52] |

Breugelmans P, Leroy B, Bers K, et al. Proteomic study of linuron and 3, 4-dichloroaniline degradation by Variovorax sp. WDL1: evidence for the involvement of an aniline dioxygenase-related multicomponent protein[J]. Research in Microbiology, 2010, 161(3): 208-218. DOI:10.1016/j.resmic.2010.01.010 |

| [53] |

Bers K, Leroy B, Breugelmans P, et al. A novel hydrolase identified by genomic-proteomic analysis of phenylurea herbicide mineralization by Variovorax sp. strain SRS16[J]. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 2011, 77(24): 8754-8764. DOI:10.1128/AEM.06162-11 |

| [54] |

Gu T, Zhou C, Sørensen SR, et al. The novel bacterial N-demethylase PdmAB is responsible for the initial step of N, N-dimethyl-substituted phenylurea herbicide degradation[J]. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 2013, 79(24): 7846-7856. DOI:10.1128/AEM.02478-13 |

| [55] |

Megharaj M, Ramakrishnan B, Venkateswarlu K, et al. Bioremediation approaches for organic pollutants: a critical perspective[J]. Environment International, 2011, 37(8): 1362-1375. DOI:10.1016/j.envint.2011.06.003 |

| [56] |

Cao MX, Sato SJ, Behrens M, et al. Genetic engineering of maize (Zea mays) for high-level tolerance to treatment with the herbicide dicamba[J]. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry, 2011, 59(11): 5830-5834. DOI:10.1021/jf104233h |

| [57] |

H fer R, Boachon B, Renault H, et al. Dual function of the cytochrome P450 CYP76 family from Arabidopsis thaliana in the metabolism of monoterpenols and phenylurea herbicides[J]. Plant Physiology, 2014, 166(3): 1149-1161. DOI:10.1104/pp.114.244814 |

2017, Vol. 44

2017, Vol. 44