扩展功能

文章信息

- 刘开力, 赫英舸, 于乐祥, 陈瑶, 赫荣乔

- Liu Kai-li, He Ying-ge, Yu Le-xiang, CHEN Yao, He Rong-qiao

- APP/PS1转基因老年性痴呆模型小鼠肠道甲醛浓度异常升高

- Markedly elevated formaldehyde in the cecum of APP/PS1 transgenic mouse model of Alzheimer's disease

- 微生物学通报, 2017, 44(8): 1761-1766

- Microbiology China, 2017, 44(8): 1761-1766

- DOI: 10.13344/j.microbiol.china.176008

-

文章历史

- 收稿日期: 2017-05-01

- 接受日期: 2017-06-08

- 优先数字出版日期(www.cnki.net): 2017-06-12

2. 西南医科大学 四川 泸州 646000

2. Southwest Medical University, Luzhou, Sichuan 646000, China

肠道菌群约占人类共生微生物的95%,构成了影响人类健康的重要内在环境因素[1]。在消化、营养及免疫等方面,其发挥对机体健康的保护作用[2]。越来越多的证据表明,肠道微生物与中枢神经系统的功能之间具有密切的联系,并影响脑的功能和行为。肠道微生物被认为是通过“微生物-肠道-脑轴(microbiota-Gut-Brain axis)”对中枢神经系统产生影响[3]。随着对肠道共生微生物的深入研究,一些中枢神经系统的疾病被证实与肠道共生菌群的失调相关,如自闭症[4]、抑郁症[5]、帕金森病[6]等。最近,阿尔茨海默病(Alzheimer’s disease,AD,俗称“老年性痴呆”)的发生发展也被证明与肠道菌群相关,并认为AD的发病可能始于肠道[7]。

我国人口老龄化日趋严重,老年人口约占我国总人口的10%以上。到2050年,我国将有800-1200万AD患者,严重危害老年人的身心健康和生活质量,给患者造成痛苦,给家庭和社会带来沉重的经济和精神负担。AD是一种常见的中枢神经系统退行性疾病,约占所有老年痴呆的60%-80%[8],主要表现为渐进性记忆和认知损害,包括人格改变及语言障碍等[9]。因此,研究老年性痴呆的发生发展机制,不但具有理论意义,同时具有潜在的重要应用价值。

甲醛具有强烈的毒性,小鼠处于气态甲醛环境中,可出现明显认知能力下降,产生抑郁、焦虑等行为[10]。Kilburn等发现,在解剖或病理实验室工作的技术人员,由于长期接触福尔马林(37%甲醛),在退休后发生痴呆的概率显著高于同龄对照[11]。王佳琬等观察到,老年人( > 65岁)经历大型或长时间手术,发生手术后认知损害(post operative cognitive dysfunction,POCD)的概率会显著增加,而发生POCD患者尿甲醛浓度,显著高于未发生POCD的患者[12]。杨美凤等采用低浓度甲醇喂食年轻猕猴(3-5岁),检测到猴脑脊液甲醛浓度显著升高,学习记忆能力下降,脑内出现老年斑(Aβ淀粉样沉积),神经Tau蛋白异常磷酸化等老年性痴呆的典型病理征兆[13-14]。临床实验表明,阿尔兹海默病病人内源甲醛的浓度与其认知损害程度呈正相关[15]。

APP/PS1转基因老年性痴呆小鼠是目前国内外最常用于AD研究的动物模型鼠[16],被广泛用于AD的发病因素、病理机制、药效学等研究。本文选用APP/PS1转基因小鼠作为对象,以野生型C57BL/6J小鼠为对照,分析和比较肠道内甲醛的含量,以探索AD模型鼠肠道菌群甲醛代谢的状况。

1 材料与方法 1.1 材料7月龄APP/PS1转基因小鼠(n=8) 和相同月龄C57BL/6J野生型小鼠(n=9) 来自北京华阜康生物科技股份有限公司。APP/PS1实验小鼠和C57BL/6J对照小鼠均在相同条件下饲养。

1.2 主要试剂和仪器2, 4-二硝基苯肼(2, 4-dinitrophenylhydrazine,DNPH)、三氯乙酸、乙腈及甲醛,德国Sigma公司。LC-20A高效液相色谱仪UV-HPLC、SPD-M20A二极管阵列检测器,日本岛津公司;色谱柱:LiChrospher 100 RP-18 (250 mmx4.6 mmx5 mm),德国Merck公司。

1.3 肠道消化物的收集实验开始前,称小鼠体重和血糖。处死后,立刻取肠段。从胃到肛门的方向,依次分取小鼠肠段,即十二指肠、小肠、盲肠、结肠;肠道截取后,在冰浴中迅速将小肠、盲肠和结肠内的消化物分别取出,称量湿重,迅速进行甲醛测定。由于十二指肠内消化物非常少,无法测定其消化物内的甲醛浓度。

1.4 肠段的截取与收集消化物收集后,立刻采用10倍于肠道组织体积的预冷(4℃)生理盐水灌洗肠道3次,包括十二指肠、小肠、盲肠、结肠肠段,洗净后,迅速进行甲醛的测定。

1.5 肠道消化物甲醛的测定样品制备:取不同肠段内的消化物各1.0 g,加入10%三氯乙酸溶液(10 ml),混匀后4 ℃、13 000 r/min离心30 min。

取0.4 ml上清、0.1 ml 2, 4-二硝基苯肼(1.0 g/L)和0.5 ml乙腈混匀后,60 ℃保温30 min,4 ℃、13 000 r/min离心10 min,取上清用于HPLC分析甲醛。甲醛测定的具体方法参考本实验室的2, 4-二硝基苯肼HPLC方法[17]。

1.6 肠壁组织甲醛的测定样品制备:取不同肠段各1.0 g,加入10%三氯乙酸溶液(10 ml),加入0.5 mL repa组织裂解液匀浆1 min,4 ℃、13 000 r/min离心30 min,取0.4 ml上清测定甲醛的含量。

1.7 数据统计采用Graphpad软件对获得的数据进行one-Way ANOVA统计分析并作图,数值使用平均值±标准误差(S.E.M)表示,P < 0.05时被认为有显著性差异。

2 结果与讨论 2.1 小鼠体重和血糖的比较对实验小鼠和对照小鼠的基本生理状况进行了比较,分别称量APP/PS1转基因小鼠和C57BL/6J小鼠的体重,如图 1a所示,两组小鼠的体重无显著差异(P > 0.05)。同时对两组小鼠的血糖进行了分析,APP/PS1转基因小鼠的血糖有轻微升高(图 1b),但尚未达到显著差异(P=0.09)。

|

| 图 1 APP/PS1转基因小鼠与C57BL/6J野生型小鼠的体重和血糖的比较 Figure 1 Comparison of body weight and blood sugar between APP/PS1 transgenic mice (n=8) and C57BL/6J mice (n=9) before they participated the experiments |

|

|

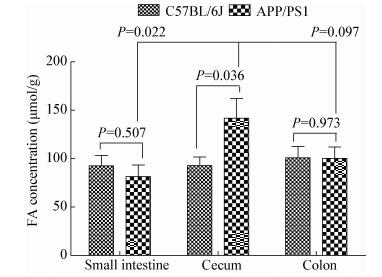

为了比较APP/PS1转基因小鼠与C57BL/6J野生型小鼠肠道内甲醛含量,采用HPLC偶联DNPH显色法[17],对不同肠段的消化物进行甲醛含量分析。结果显示(表 1),APP/PS1老年性痴呆转基因小鼠盲肠内消化物的甲醛含量最高,并且显著(P=0.036) 高于C57BL/6J小鼠(图 2)。两组鼠的小肠和结肠消化物中的甲醛含量无显著差异(P > 0.05)。

| Samples | Formaldehyde concentrations in digestion contents (μmol/g) | Formaldehyde concentrations in intestinal walls (μmol/g) | |||

| APP/PS1 | C57BL/6J | APP/PS1 | C57BL/6J | ||

| Duodenum | - | - | 57.75±5.95 | 55.94±4.53 | |

| Small intestine | 81.57±11.98 | 92.51±10.83 | 84.34±8.30 | 60.35±7.78 | |

| Cecum | 141.87±20.22 | 92.84±8.96 | 114.95±10.06 | 126.44±12.02 | |

| Colon | 100.27±11.74 | 100.85±11.94 | 100.23±14.83 | 80.90±10.15 | |

| Note: -: No data were shown because the amount of digestion contents were too few to perform the analysis. | |||||

|

| 图 2 APP/PS1转基因小鼠与C57BL/6J野生型小鼠肠道消化物的甲醛含量 Figure 2 Comparison of concentrations of formaldehyde in the intestinal digestion contents between APP/PS1 transgenic mice and C57BL/6J wildtype mice Note: Concentrations of formaldehyde in small intestine, cecum and colon of APP/PS1 and C57BL/6J mice were determined with HPLC-coupled with DNPH absorption measurements. The levels of the cecum formaldehyde of APP/PS1 mice (n=8) were significantly (P < 0.05) higher than C57BL/6J wildtype mice (n=9) used as control. However, levels of formaldehyde in small intestine and colon between both APP/PS1 and C57BL/6J mice were not markedly different (P > 0.05). |

|

|

APP/PS1转基因小鼠盲肠消化物甲醛浓度显著高于其自身的小肠(P=0.022) 和略高于大肠消化物(P=0.097)。这些结果提示,老年性痴呆模型小鼠盲肠内甲醛蓄积,而且浓度高于其他肠道的消化物。

2.3 APP/PS1转基因小鼠肠壁组织的甲醛含量甲醛能够进入细胞[18],从而被肠道吸收。为了进一步了解甲醛在肠道内的分布,测定了十二指肠、小肠、盲肠以及结肠壁内甲醛的含量(表 1)。虽然APP/PS1转基因小鼠盲肠壁内的甲醛浓度与对照鼠的浓度相比无显著差异。但可以观察到,盲肠壁的甲醛含量最高,其次是结肠和小肠壁组织(图 3)。APP/PS1转基因小鼠小肠壁内的甲醛含量较对照组有升高,但无统计学上的显著差异(P < 0.052)。然而,比较各肠段壁内的甲醛含量显示,无论实验组还是对照组,其盲肠壁的甲醛含量为最高。

|

| 图 3 APP/PS1转基因小鼠肠壁组织中的甲醛含量 Figure 3 Concentrations of formaldehyde in the intestinal wall of APP/PS1 transgenic mice 注:与C57BL/6J小鼠比较,APP/PS1转基因小鼠小肠壁的甲醛含量升高,接近显著差异(P < 0.052);但其他肠壁中甲醛的含量,两组相比,未见显著升高(P > 0.05). Note: Conditions were as for Materials and Methods, except that concentrations of formaldehyde in the intestinal wall were determined. Levels of formaldehyde in small intestinal walls of APP/PS1 and C57BL/6J mice were observably different (P < 0.052). However, levels of formaldehyde in the duodenum, cecum, and colon walls were not significantly different (P > 0.05). |

|

|

APP/PS1模型组盲肠消化物的甲醛浓度平均值为141.87 μmol/kg,而对照组为92.84 μmol/kg,AD鼠增加了52.8%。从肠道壁来看,尽管AD模型鼠和野生型鼠的盲肠壁不存在显著差异(P > 0.05),但盲肠壁内的甲醛含量均高于十二指肠、小肠、结肠壁组织。说明甲醛的蓄积主要发生在盲肠。

通过比较APP/PS1与C57BL/6J小鼠肠道内甲醛含量,作者认为,肠道菌群是人体内产生甲醛的主要来源之一,其理由是:(1) 在哺乳动物细胞培育过程中,细胞自身可以产生少量甲醛,如小鼠神经母细胞瘤N2a细胞中约为5 μmol/L[19],血管上皮bEnd.3细胞中约为4 μmol/L,远低于肠道内甲醛的水平,提示肠道壁细胞对肠道甲醛的贡献很小[20];(2) C57BL/6J野生型小鼠脑内甲醛含量仅为14.2±2.1 μmol/L[21],远低于其盲肠消化物的浓度92.84±8.96 μmol/L;(3) C57BL/6J野生型小鼠盲肠壁内甲醛浓度为126.44±12.02 μmol/L,说明甲醛能够进入肠壁组织;(4) APP/PS1转基因小鼠盲肠消化物甲醛浓度高达141.87±20.22 μmol/L,肠壁为114.95±10.06 μmol/L,接近野生型小鼠脑甲醛浓度的10倍;(5) 已有研究报道,甲醛可以迅速通过细胞,从而被肠道吸收[18, 22]。以上结果显示,甲醛可以由肠道菌群产生,从而被肠道吸收。

2.5 老年性痴呆病人肠道内微生物菌群的变化在肠道菌群中,有益生菌和致病菌,它们均能够产生和代谢甲醛。肠道内的益生菌,如Lactobacillus fermentum strain NS9、Lactobacillus helveticus及Bifidobacteria longum三种益生菌对人类的认知甚至学习记忆有益(表 2)。它们分别含有ADH、ALDH及ADH甲醛代谢酶,具有降解甲醛的作用。Lactobacillus fermentum strain NS9[24, 34]和Lactobacillus helveticus[25]具有改善大鼠心理认知状态、增强小鼠学习记忆能力的作用[26]。

| Gut microbiota | Classification | Relation with AD | References |

| Lactobacillus fermentum strain NS9 | probiotic | Ameliorate cognitive impairment | Park, et al., 2012[23]; Wang, et al., 2015[24] |

| Lactobacillus helveticus | probiotic | Ameliorate cognitive impairment | Luo, et al., 2014[25]; Ohsawa, et al., 2015[26] |

| Bifidobacteria longum | probiotic | Ameliorate cognitive impairment | Del Re, et al., 2000[27]; Savignac, et al., 2015[28] |

| Chlamydia pneumoniae | pathogen | Associated with AD | Little, et al., 2004[29]; Gérard, et al., 2006[30] |

| Helicobacter pylori | pathogen | Associated with AD | Roubaud-Baudron, et al., 2012[31]; Kountouras, et al., 2012[32] |

| Toxoplasma gondii | pathogen | Associated with AD | Prandota, 2014[33] |

另一方面,在老年性痴呆发生发展过程中,肠道内也寄生有一些致病菌,如Chlamydia pneumoniae[29-30]、Helicobacter pylori[31-32]及Toxoplasma gondii[33],它们分别与老年性痴呆相关,在AD发生发展的过程中发挥不良作用。这些研究工作证实,在老年性痴呆的进程中,患者体内的肠道菌群发生改变,导致肠道菌群的代谢失调,从而影响脑的认知功能。

3 结论肠道微生物菌群是体内甲醛的主要来源,对于盲肠来说,无论是消化物还是肠壁组织,其甲醛含量均比其他肠段要明显高得多。相比之下,老年性痴呆模型小鼠的小肠壁甲醛也有较高的含量。这些结果提示,必须重视肠道菌群的甲醛产生与代谢问题,特别是老年性痴呆病人肠道菌群的甲醛代谢失调。

老年性痴呆住院患者和正常人的内源甲醛分别为13.70±5.17 mmol/L及9.61±2.90 mmol/L[21]。内源甲醛作为临床检验的生物标志物,可以用于老年认知损害的指标,但该临床指标不能用来区分阿尔茨海默病与血管性痴呆(VD)。然而,AD和VD可以通过病史进行鉴别诊断。“微生物-肠道-脑轴”不但与衰老相关,也与认知损害相关[35]。对于65岁以上的老人,进行尿和粪便甲醛的测定,对出现内源甲醛升高的老人,可以作为生物学标志物在流行病学和临床上药物干预方面加以应用,以利于早期发现、早期诊断,以肠道甲醛代谢为药物作用靶点进行早期预防,从而减少甲醛对中枢神经系统和认识的损害。

| [1] |

Xu YH, Zhou H, Zhu Q. The impact of microbiota-gut-brain axis on diabetic cognition impairment[J]. Frontiers in Aging Neuroscience, 2017, 9: 106. DOI:10.3389/fnagi.2017.00106 |

| [2] |

Hooper LV, Gordon JI. Commensal host-bacterial relationships in the gut[J]. Science, 2001, 292(5519): 1115-1118. DOI:10.1126/science.1058709 |

| [3] |

Cryan JF, Dinan TG. Mind-altering microorganisms: the impact of the gut microbiota on brain and behaviour[J]. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 2012, 13(10): 701-712. DOI:10.1038/nrn3346 |

| [4] |

Finegold SM, Dowd SE, Gontcharova V, et al. Pyrosequencing study of fecal microflora of autistic and control children[J]. Anaerobe, 2010, 16(4): 444-453. DOI:10.1016/j.anaerobe.2010.06.008 |

| [5] |

Naseribafrouei A, Hestad K, Avershina E, et al. Correlation between the human fecal microbiota and depression[J]. Neurogastroenterology and Motility, 2014, 26(8): 1155-1162. DOI:10.1111/nmo.2014.26.issue-8 |

| [6] |

Scheperjans F, Aho V, Pereira PAB, et al. Gut microbiota are related to Parkinson's disease and clinical phenotype[J]. Movement Disorders, 2015, 30(3): 350-358. DOI:10.1002/mds.26069 |

| [7] |

Hu X, Wang T, Jin F. Alzheimer's disease and gut microbiota[J]. Science China-Life Sciences, 2016, 59(10): 1006-1023. DOI:10.1007/s11427-016-5083-9 |

| [8] |

Alzheimer's Association. 2015 Alzheimer's disease facts and figures[J]. Alzheimers & Dementia, 2015, 11(3): 332-384. |

| [9] |

Reitz C, Brayne C, Mayeux R. Epidemiology of Alzheimer disease[J]. Nature Reviews Neurology, 2011, 7(3): 137-152. DOI:10.1038/nrneurol.2011.2 |

| [10] |

Li T, Su T, He YG, et al. Brain formaldehyde is related to water intake behavior[J]. Aging and Disease, 2016, 7(5): 561-584. DOI:10.14336/AD.2016.0323 |

| [11] |

Kilburn KH, Warshaw R, Thornton JC. Formaldehyde impairs memory, equilibrium, and dexterity in histology technicians: effects which persist for days after exposure[J]. Archives of Environmental Health, 1987, 42(2): 117-120. DOI:10.1080/00039896.1987.9935806 |

| [12] |

Wang JW, Su T, Liu Y, et al. Postoperative cognitive dysfunction is correlated with urine formaldehyde in elderly noncardiac surgical patients[J]. Neurochemical Research, 2012, 37(10): 2125-2134. DOI:10.1007/s11064-012-0834-x |

| [13] |

Yang MF, Lu J, Miao JY, et al. Alzheimer's disease and Methanol Toxicity (Part 1): chronic methanol feeding led to memory impairments and tau hyperphosphorylation in mice[J]. Journal of Alzheimer's Disease, 2014, 41(4): 1117-1129. |

| [14] |

Yang MF, Miao J, Rizak J, et al. Alzheimer's disease and Methanol Toxicity (Part 2): lessons from four rhesus macaques (Macaca mulatta) chronically fed methanol[J]. Journal of Alzheimer's Disease, 2014, 41(4): 1131-1147. |

| [15] |

Tong ZQ, Zhang JL, Luo WH, et al. Urine formaldehyde level is inversely correlated to mini mental state examination scores in senile dementia[J]. Neurobiology of Aging, 2011, 32(1): 31-41. DOI:10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2009.07.013 |

| [16] |

Webster SJ, Bachstetter AD, Nelson PT, et al. Using mice to model Alzheimer's dementia: an overview of the clinical disease and the preclinical behavioral changes in 10 mouse models[J]. Frontiers in Genetics, 2014, 5: 88. |

| [17] |

Su T, Wei Y, He RQ. Assay of brain endogenous formaldehyde with 2, 4-dinitrophenylhydrazine through UV-HPLC[J]. Progress in Biochemistry and Biophysics, 2011, 38(12): 1171-1177. (in Chinese) 苏涛, 魏艳, 赫荣乔. 改良2, 4-二硝基苯肼法测定脑内源甲醛[J]. 生物化学与生物物理进展, 2011, 38(12): 1171-1177. |

| [18] |

Shcherbakova LN, Tel'pukhov VI, Trenin SO, et al. Permeability of the blood-brain barrier to intra-arterial formaldehyde[J]. Bulletin of Experimental Biology and Medicine, 1986, 102(11): 573-575. |

| [19] |

Wang J, Zhou J, Mo WC, et al. Accumulation of simulated pathological level of formaldehyde decreases cell viability and adhesive morphology in neuronal cells[J]. Progress in Biochemistry and Biophysics, 2017. (in Chinese) 王腈, 周均, 莫炜川, 等. 病理浓度甲醛的累积导致小鼠神经母瘤细胞活力及粘附能力下降[J]. 生物化学与生物物理进展, 2017. DOI:10.16476/j.pibb.2017.0062 |

| [20] |

Chen XX, Su T, He YG, et al. Spatial cognition decline caused by excess formaldehyde in the lysosome[J]. Progress in Biochemistry and Biophysics, 2017, 44(6): 486-494. (in Chinese) 陈茜茜, 苏涛, 赫英舸, 等. 氧化应激对溶酶体储存与转运甲醛的影响[J]. 生物化学与生物物理进展, 2017, 44(6): 486-494. |

| [21] |

Li Y, Song ZY, Ding YJ, et al. Effects of formaldehyde exposure on anxiety-like and depression-like behavior, cognition, central levels of glucocorticoid receptor and tyrosine hydroxylase in mice[J]. Chemosphere, 2016, 144: 2004-2012. DOI:10.1016/j.chemosphere.2015.10.102 |

| [22] |

Lu J, Miao JY, Su T, et al. Formaldehyde induces hyperphosphorylation and polymerization of Tau protein both in vitro and in vivo[J]. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA)-General Subjects, 2013, 1830(8): 4102-4116. DOI:10.1016/j.bbagen.2013.04.028 |

| [23] |

Park JH, Kim Y, Kim SH. Green tea extract (Camellia sinensis) fermented by Lactobacillus fermentum attenuates alcohol-induced liver damage[J]. Bioscience, Biotechnology, and Biochemistry, 2012, 76(12): 2294-2300. DOI:10.1271/bbb.120598 |

| [24] |

Wang T, Hu X, Liang S, et al. Lactobacillus fermentum NS9 restores the antibiotic induced physiological and psychological abnormalities in rats[J]. Beneficial Microbes, 2015, 6(5): 707-717. DOI:10.3920/BM2014.0177 |

| [25] |

Luo J, Wang T, Liang S, et al. Ingestion of Lactobacillus strain reduces anxiety and improves cognitive function in the hyperammonemia rat[J]. Science China-life Sciences, 2014, 57(3): 327-335. DOI:10.1007/s11427-014-4615-4 |

| [26] |

Ohsawa K, Uchida N, Ohki K, et al. Lactobacillus helveticus-fermented milk improves learning and memory in mice[J]. Nutritional Neuroscience, 2015, 18(5): 232-240. DOI:10.1179/1476830514Y.0000000122 |

| [27] |

Del Re B, Sgorbati B, Miglioli M, et al. Adhesion, autoaggregation and hydrophobicity of 13 strains of Bifidobacterium longum[J]. Letters in Applied Microbiology, 2000, 31(6): 438-442. DOI:10.1046/j.1365-2672.2000.00845.x |

| [28] |

Savignac HM, Tramullas M, Kiely B, et al. Bifidobacteria modulate cognitive processes in an anxious mouse strain[J]. Behavioural Brain Research, 2015, 287: 59-72. DOI:10.1016/j.bbr.2015.02.044 |

| [29] |

Little CS, Hammond CJ, MacIntyre A, et al. Chlamydia pneumoniae induces Alzheimer-like amyloid plaques in brains of BALB/c mice[J]. Neurobiology of Aging, 2004, 25(4): 419-429. DOI:10.1016/S0197-4580(03)00127-1 |

| [30] |

Gérard HC, Dreses-Werringloer U, Wildt KS, et al. Chlamydophila(Chlamydia) pneumoniae in the Alzheimer's brain[J]. Fems Immunology and Medical Microbiology, 2006, 48(3): 355-366. DOI:10.1111/fim.2006.48.issue-3 |

| [31] |

Roubaud-Baudron C, Krolak-Salmon P, Quadrio I, et al. Impact of chronic Helicobacter pylori infection on Alzheimer's disease: preliminary results[J]. Neurobiology of Aging, 2012, 33(5): 1009.e11-1009.e19. DOI:10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2011.10.021 |

| [32] |

Kountouras J, Boziki M, Zavos C, et al. A potential impact of chronic Helicobacter pylori infection on Alzheimer's disease pathobiology and course[J]. Neurobiology of Aging, 2012, 33(7): e3-e4. DOI:10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2012.01.003 |

| [33] |

Prandota J. Possible link between Toxoplasma gondii and the anosmia associated with neurodegenerative diseases[J]. American Journal of Alzheimers Disease and Other Dementias, 2014, 29(3): 205-214. DOI:10.1177/1533317513517049 |

| [34] |

Yüksekdağ ZN, Beyath Y, Aslim B. Metabolic activities of Lactobacillus spp. strains isolated from kefir[J]. Nahrung-Food, 2004, 48(3): 218-220. DOI:10.1002/(ISSN)1521-3803 |

| [35] |

Scott KA, Ida M, Peterson VL, et al. Revisiting Metchnikoff: Age-related alterations in microbiota-gut-brain axis in the mouse[J]. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity, 2017. DOI:10.1016/j.bbi.2017.02.004 |

2017, Vol. 44

2017, Vol. 44