扩展功能

文章信息

- 陈玉连, 潘杰, 周之超, 王风平, 李猛

- CHEN Yu-Lian, PAN Jie, ZHOU Zhi-Chao, WANG Feng-Ping, LI Meng

- 滨海深古菌的研究进展

- Progress in studies on Bathyarchaeota in coastal ecosystems

- 微生物学通报, 2017, 44(7): 1690-1698

- Microbiology China, 2017, 44(7): 1690-1698

- DOI: 10.13344/j.microbiol.china.170173

-

文章历史

- 收稿日期: 2017-03-01

- 接受日期: 2017-05-11

- 优先数字出版日期(www.cnki.net): 2017-06-06

2. 深圳大学生命与海洋科学学院 广东 深圳 518060;

3. 香港大学生物科学学院 香港;

4. 上海交通大学生命科学技术学院微生物代谢国家重点实验室 上海 200240;

5. 上海交通大学海洋工程国家重点实验室 上海 200240

2. College of Life Sciences and Oceanography, Shenzhen University, Shenzhen, Guangdong 518060, China;

3. School of Biological Sciences, The University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong, China;

4. School of Life Sciences and Biotechnology, Shanghai Jiao Tong University, Shanghai 200240, China;

5. 5State Key Laboratory of Ocean Engineering, Shanghai Jiao Tong University, Shanghai 200240, China

1990年,Woese等[1]通过对核糖体小亚基(16S rRNA)基因序列的同源性进行系统发育比较,将生物划分为三大域(Domain),包括真核生物域(Eucarya)、细菌生物域(Bacteria)和古菌生物域(Archaea),并将古菌生物域分为广古菌门(Euryarchaeota)和泉古菌门(Crenarchaeota)。至此,古菌作为一个新的生物大类,逐渐受到广泛关注和深入研究。古菌作为微生物重要组成部分之一,广泛分布于不同生境,驱动着全球生物地球化学循环。但大部分古菌难培养,研究者们对古菌分类和功能的了解有限。

随着高通量测序技术的快速发展,研究者们对古菌的认识有了突破性的进展。古菌由最初的两个门类增加到目前的28个门类,包括纳古菌门(Nanoarchaeota)[2]、奇古菌门(Thaumarchaeota)[3]、初生古菌门(Korarchaeota)[4]、曙古菌门(Aigarchaeota)[5]、微古菌门(Parvarchaeota)[6]、深古菌门(Bathyarchaeota)[7]、洛基古菌门(Lokiarchaeota)[8]、索尔古菌门(Thorarchaeota)[9]、佩斯古菌门(Pacearchaeota)[10]、乌斯古菌门(Woesearchaeota)[10]、韦斯特古菌门(Verstraetearchaeota)[11]、奥丁古菌门(Odinarchaeota)和海姆达尔古菌门(Heimdallarchaeaota)[12]等。新发现的古菌门类广泛分布于海洋环境,且它们的16S rRNA基因的系统发育分析显示它们与已知的广古菌门和泉古菌门亲缘关系较远[10],暗示着它们的生态功能可能存在显著差异。

深古菌,原名为MCG古菌(Miscellaneous Crenarchaeotal Group),包含一类多样性极高的古菌类群,其分布广泛、生物量极高,据推测是地球上含量最为丰富的微生物之一。此外,深古菌还具有多样的生理生化代谢特征,可能在全球物质和能量循环过程中发挥着重要作用。然而,至今尚未有对其成功培养的案例。研究者们对于深古菌的科学探索还处于初步阶段,仍有很多问题尚待解答。随着各类生境中深古菌基因组信息的不断发现和纯培养工作的不断探索,深古菌门成员的生态分布、代谢和功能特征逐渐清晰,这类古菌的研究成果将对整个微生物研究有着重大的影响。

1 深古菌门的确立最初MCG古菌被命名为陆地型MCG古菌(Terrestrial miscellaneous crenarchaeotal group)[13],被认为主要分布于陆地生境中,是泉古菌门的一个分支类群。2003年,Inagaki等[14]在对鄂霍次克海沉积物微生物调查中发现这类古菌,它是火山灰沉积层古菌的主要组成类群,因此将其改名为MCG古菌。2012年,Li等[15]在对南海沉积物的质粒文库中含MCG古菌16S rRNA基因长片段进行测序分析,发现MCG古菌的进化距离与已知其他古菌门类相距较远,认为其是古菌域的一个新的类群。同年,Kubo等[16]通过汇总和分析SILVA数据库中(SSU Ref NR106和SSU Parc106) 4 720个深古菌核糖体小亚基基因序列,建立了第一个全球范围内综合性的深古菌系统发育树,使研究者们对深古菌的系统发育地位和结构有了全面的了解,为研究其在全球生态环境的分布和功能奠定了基础。2013年,Lloyd等[17]对MCG古菌进行了第一次单细胞基因组测序,并对MCG古菌的部分单拷贝基因进行了系统发育分析,推测MCG古菌的分类地位处于奇古菌门和曙古菌门之间,是一个新的古菌门类。2014年,上海交通大学王风平课题组通过对MCG古菌的23S rRNA-16S rRNA串联基因进行系统发育分析,发现MCG古菌在系统发育树上显著区别于其他古菌门类,属于一类较老的古菌门类。鉴于该古菌广泛和丰富地分布在全球深海沉积物中,MCG古菌被重新命名为深古菌门(Bathyarchaeota)[7]。至此,深古菌门被确立为一个新的古菌门类,由于其具有多样性、分布和生理生化途径的特殊性,对它的深入研究将有助于研究者们理解原核生物在全球物质和能量循环中的重要作用。

2 深古菌的生理生化特征由于深古菌的广泛分布和较高的生物量,以及深古菌的生理生化功能对于全球生态系统和环境变化影响巨大,因此对于深古菌生理生化功能的探索成为了古菌研究的热点。

此前,通过海洋和河口等沉积物的宏基因组研究发现,深古菌具有潜在的降解蛋白质[17]、利用有机碳[18]和分解芳香族化合物[7]等异养代谢途径。Webster等[19]和Seyler等[20]利用DNA同位素标记方法分别对河口和盐沼泽地沉积物的宏基因组进行研究后推测,深古菌可能是一类利用低分子有机酸或高分子生物聚合物等有机物作为碳源的异养型微生物。但是另一些研究发现,深古菌具备利用二氧化碳和氢气作为物质来源的自养代谢途径[21-23],同时发现深古菌基因组中有mcrA基因,暗示深古菌具有产甲烷的潜力[21]。此外,通过河口沉积物中古菌定量分析推测,深古菌可能是一类自养型或利用含有衰竭态13C有机物的异养型微生物[24]。

此外,在众多生境的宏基因组研究中还发现,部分深古菌基因组中含有异化还原亚硝酸盐[23]和硫酸盐的关键功能基因[25],表明深古菌也可能参与氮硫化合物的代谢,对氮硫元素的生物地球化学循环有着重要的意义。

从上述研究中可知,深古菌的生理生化功能具有较高的多样性。然而,由于没有成功培养案例,目前对深古菌的代谢研究还停留在基因组水平上的预测,对于深古菌的生理生化功能的了解仍有限。

3 深古菌的地理分布和多样性 3.1 深古菌的分布最初深古菌被发现分布于陆地环境中,如南非金矿深层地下水、湖泊和热泉环境[13]。随后在深海沉积物中发现了大量深古菌,其丰度占据了古菌大部分。例如,在深海钻探站点Peru Margin Site 1229和Peru Margin Site 1227中,深古菌丰度分别占据了古菌总丰度的92%和48%;在鄂霍次克海中的火山灰层中,深古菌占71%;在Nankai Trough的弧前盆地沉积物中占47.5%;在Nankai Trough ODP 1173层积岩中占20.6%,在地中海更新世腐殖质的所有层中的占比平均高达83.3%[14, 26-31]。此外,Fry等[32]对海面下水层的16S rRNA基因的47个克隆文库进行了分析,发现深古菌占据古菌的33%,并预测在海洋深部生物圈中,深古菌占据了古菌总量的10%-100% (平均约为30%-60%)。这些研究表明深古菌的分布不仅仅局限于陆地环境。

最近,随着宏基因组学的不断发展,在河口沉积层[33]、盐沼泽地[20]、地下水层[21]等生境中也发现大量深古菌分布,证明了深古菌的广泛分布特性。据推测,深古菌是迄今为止发现最为广泛的未培养古菌门类,并且深古菌的细胞数量庞大,在自然界中达到(2.0-3.9)×1028个细胞,是地球上含量最为丰富的微生物之一[16]。

3.2 深古菌的多样性对深古菌的认知过程与分子生物学发展息息相关,深古菌的多样性研究和亚群(subgroup)建立也是一个不断发展的过程。

2006年,Sørensen和Teske[34]分析了环境16S rRNA基因序列,将数百个MCG古菌16S rRNA基因序列分为4个亚群(MCG 1-4)。之后更多序列被不断发现。Jiang等[35]对MCG古菌16S rRNA基因进行了综合的系统发育分析,将MCG古菌分为7个亚群(MCG A-G)。2012年,Kubo等[16]对SILVA数据库中的核糖体小亚基基因序列进行了更为完整的系统发育分析,将MCG古菌分为了17个亚群(Subgroup 1-17)。其中,Subgroup 1-12是之前研究中已经确立的亚群,或者用邻接法(Neighbor-Joining)和最大似然法(Maximum-Likelihood)构建的进化树之间相互吻合的单分支,而Subgroup 13-17为不同进化模型和系统发育方法下不稳定的分支。2015年,Fillol等[36]对数据库中新增的深古菌16S rRNA基因序列进行分析,增添了Subgroup 18和19两个置信度较高的亚群,并将Subgroup 5细分为Subgroup 5a、5b和5bb。最近,He等在对深古菌基因组分析研究中提出了两个不同于其它亚群的新类群[22]。至此,基于系统发育分析,深古菌门共有23个较为明确的亚群,不同的深古菌亚群之间16S rRNA基因序列的相似度在75%-94%之间,表明深古菌具有较高的类群多样性。

针对深古菌多样性和丰度的调查研究中,为快速精准地测定各类生境中深古菌的分布特征,一系列特异性引物和探针被提议用于古菌或深古菌的快速鉴定(表 1)。最初,研究者们广泛采用针对总古菌的引物958F和1048R进行环境宏基因组的PCR和测序,对得到的序列进行分析,获取深古菌的多样性和丰度信息。2012年,Kubo等[16]对深古菌的16S rRNA基因序列进行引物设计,得到了MCG410/MCG493和MCG528/MCG732两对引物,利用计算机模拟评估,其结果显示MCG410、MCG493、MCG528和MCG732对于Subgroup 1-12的平均覆盖率分别可达44%、79%、87%和27%,由于MCG528/MCG732引物对于深古菌的覆盖率和特异性较高,因此被推荐用于深古菌的检测和量化。但是此引物对Subgroup 13-17的覆盖率较差,且不适用于定量淡水和沉积物中的深古菌[36]。Fillol等[38]针对淡水起源的深古菌序列设计了新的引物MCG242dF和MCG678R,对于淡水起源的深古菌具有良好的覆盖度。然而,引物MCG242dF/ MCG678R和MCG528/MCG732在对淡水和海洋沉积物中深古菌的覆盖率和特异性分析时发现,它们在淡水沉积物cDNA库中普遍存在Subgroup 15的检测表现不佳的状况,表明针对深古菌16S rRNA基因的特异性引物还需要持续改进。

| 引物 Primer |

检测目标 Target |

序列 Sequence (5′→3′) |

参考文献 Reference |

| 958F | 总古菌 | AATTGGANTCAACGCCGC | [37] |

| 1048R major | 总古菌 | CGRCGGCCATGCACCWC | [37] |

| 1048R major | 总古菌 | CGRCRGCCATGYACCWC | [37] |

| MCG410F | 深古菌 | TCCGCTGAGGATGGCTTTT | [16] |

| MCG528F | 深古菌 | CGGTAATACCAGCTCTCCGAG | [16] |

| MCG528R | 深古菌 | CTCGGAGAGCTGGTATTACCG | [16] |

| MCG732R | 深古菌 | CGCGTTCTAGCCGACAGC | [16] |

| MCG242dF | 深古菌 | TDACCGGTDCGGGCCGTG | [36] |

| MCG678R | 深古菌 | CACCGTCGGGCGCGTTCT | [36] |

| MCG493 | 深古菌 | CTTGCCCTCTCCTTATTCC | [16] |

| MCG528 | 深古菌 | CGGAGAGCTGGTATTACC | [16] |

此外,基于宏基因组数据,一些研究已经开始对深古菌不同亚群的生理生化功能和分布环境进行了比较研究。Fillol等[38]对公共数据库中的深古菌16S rRNA基因序列以及其来源进行了分析,发现深古菌的各个亚群在不同盐度环境中的分布具有一定的规律,其中的8个亚群对于不同盐度环境具有选择性。Xiang等[39]对陆源深古菌进行了调查,发现其各个亚群之间以及与其它古菌门类之间有潜在相关性。另一方面,He等[22]对来自不同生境、归属于不同亚群深古菌基因组的功能性基因进行了分析,其中只在部分基因组中发现了Wood-Ljungdahl途径(乙酰辅酶A途径)和产乙酸途径。这些研究为深古菌的研究开启了新的思路,是未来深古菌研究的一个重要方向。

4 滨海深古菌的研究现状滨海生态系统指海岸线周围100 km之内的潮间带、潮下带以及水深200 m以下的大陆架区域[40],包括河口、滩涂、盐沼、近海、海湾、海峡、红树林与珊瑚礁等地理类型,是介于陆地和海洋之间的特殊生态系统,拥有多种多样的生态种类。由于其地理位置的特殊性,在长期的海陆交互作用及人类活动的影响下,其微生物的类型和分布具有较高的多样性,是研究微生物分布规律和生理生化功能的理想对象。

目前已经有部分研究者针对滨海生态系统的深古菌进行了研究,并取得了一定的研究成果,揭示了深古菌的一些分布规律和生理生化特征。

2012年,Kubo等[16]对11个近海和海湾的深古菌多样性进行研究发现,深古菌的相对丰度和群落结构不随沉积物中的硫酸盐还原和甲烷氧化层的深度改变而发生变化,表明深古菌可能不参与硫酸盐还原和甲烷氧化过程。在针对White Oak River河口的沉积物研究中[33],研究者发现深古菌的丰度随着沉积物的氧化还原环境的减弱而降低。深入分析发现,深古菌Subgroup 6能在低氧、硫化物含量较少的浅层沉积物中持续存在,而Subgroup 1和Subgroup 5/8则被发现存在于更深和硫化物含量更多的地下层中。所以,沉积物深度是影响深古菌亚群分布的首要变量,其次是硫化物浓度(反映氧化还原强弱)。另外,作者对深古菌基因组进行拼接分析,发现了深古菌利用H2的生理生化潜力,揭示了其自养代谢的潜力[23]。在针对珠江口流域沉积物的另一项研究中发现,深古菌占古菌比例随沉积物深度的增加而增加,而Subgroup 15的这种趋势尤为明显[41],揭示了深古菌Subgroup 15的分布特征。此外,深古菌降解芳香族化合物[7]和利用有机物[24]等独特的生理生化特征也都来源于针对滨海生态系统中深古菌类群的研究。

这些研究结果不仅揭示了深古菌不同亚群凭借多样的生理生化特征和适应环境改变的进化机制,对滨海生态系统这一复杂环境的强大适应能力,同时也从侧面证明了滨海生态系统是研究深古菌的生态分布和生理生化特征的理想对象。然而,目前对滨海深古菌的研究还主要以近岸浅海和河口附近沉积物作为主要研究对象,以其他生境作为研究区域的报道仍十分缺乏。因此,对于深古菌在其他具有特色的滨海生态系统中的研究还有待进一步深入开展。

红树林是位于热带与亚热带海洋潮间带独特的高产滨海湿地生态系统,与其他滨海生态系统相比,红树林湿地生态系统拥有较高的微生物多样性和丰度。但是目前对于红树林湿地的深古菌门相关研究几乎处于空白状态,只有少数研究报道检测到深古菌16S rRNA基因[42-43],尚无对红树林生态系统中深古菌的系统深入的研究。

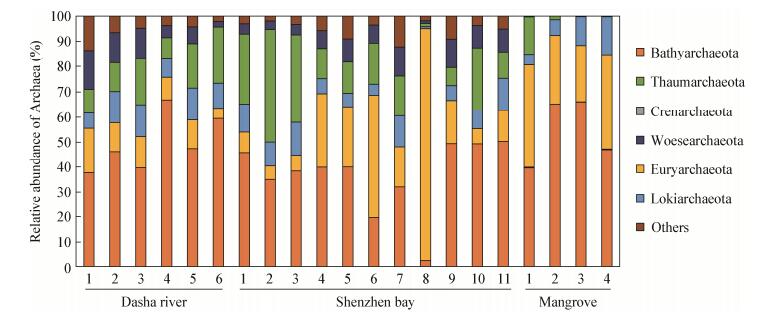

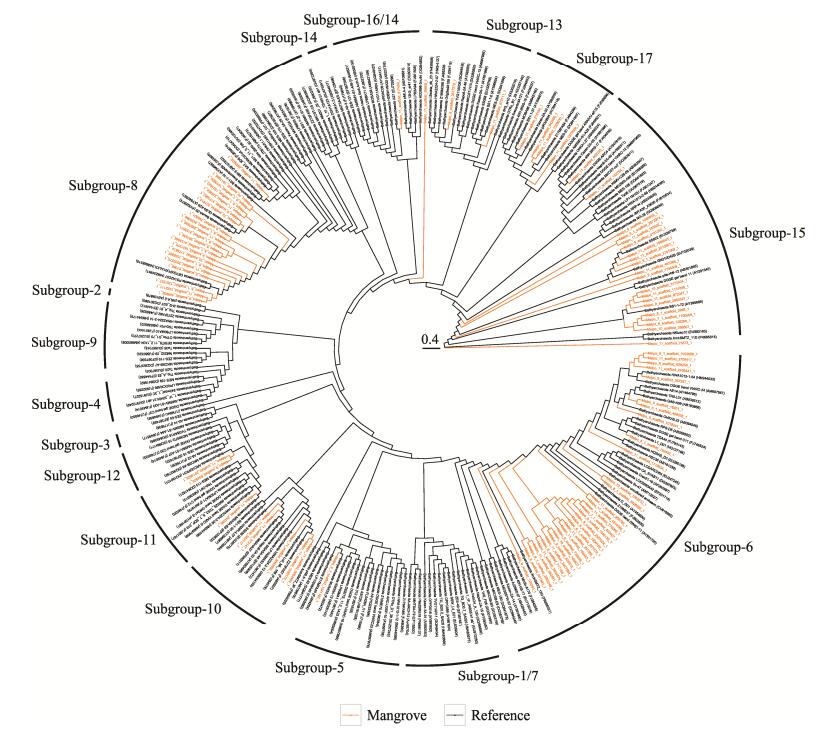

此前,本课题组已经对深圳市滨海环境的几个区域(大沙河、深圳湾、红树林)进行了一系列研究工作,针对这几个生境中深古菌的种类组成、多样性和丰度的时空变化规律等问题进行了部分前期工作。在对3个生境的古菌种群调查当中发现都含有大量的深古菌,除个别样品外,深古菌的丰度占据古菌丰度的30%-67% (图 1)。此外,大沙河和深圳湾的古菌多样性与红树林湿地有一定差别,大沙河和深圳湾的古菌门类明显高于红树林湿地,暗示红树林湿地生境在高含量的有机质影响下,深古菌可能具有较为独特的生理生化特征。特别观察到,深圳湾6、7和8号样品中深古菌含量很低,这可能是由于这3个样品的取样地点处于生蚝养殖区,底层有机质被大量消耗的缘故。此外,对不同样品的深古菌亚群进行进一步分析发现(图 2),大沙河和深圳湾的深古菌具有较高的多样性,其最高可检测到存在16种亚群;而红树林湿地的深古菌多样性稍低。在所有的样品中,Subgroup 6和8是主要的深古菌亚群,其丰度最高分别可达到60%和58%。另外,在淡咸水交界的河口附近,Subgroup 6的丰度明显降低,Subgoup 12和17的丰度明显升高,且深古菌各个亚群的多样性也有明显升高,暗示深古菌的不同亚群在淡水和咸水交界的生境中较为活跃,共同对滨海生态系统的稳定产生重要的影响。目前本课题组还对深圳红树林湿地进行了宏基因组测序和微生物基因组的构建,从中得到了较多的深古菌16S rRNA基因序列。对大于300 bp的序列进行系统发育树的构建,得到了19个深古菌Subgroup,如图 3所示。结果表明了红树林湿地深古菌的多样性丰富,其中Subgroup 6和Subgroup 8的丰度较高,与16S rRNA基因的高通量测序结果相一致。

|

| 图 1 深圳湾、大沙河和红树林湿地沉积物中的古菌组成 Figure 1 Composition of Archaea in Shenzhen Bay, Dasha River and mangrove wetland sediments |

|

|

|

| 图 2 深圳湾、大沙河和红树林湿地沉积物中的深古菌组成 Figure 2 Composition of Bathyarchaeota in Shenzhen Bay, Dasha River and mangrove wetland sediments |

|

|

|

| 图 3 最大似然法构建深圳红树林深古菌16S rRNA基因的系统发育无根树 Figure 3 Phylogenetic unrooted tree of Bathyarchaeota in Shenzhen mangrove wetland based on 16S rRNA gene sequences 注:参考序列的名称为序列来源的克隆名称;名称之后的括号为序列的GenBank登录号;外圈的标注为序列所属的亚群分类;标尺代表序列间的分歧度为40%. Note: names of reference sequences represent the names of clones or isolates; the brackets followed represent sequences' accession number in GenBank; words of outer ring represent the subgroups sequences belong; Scale bar 0.4 represents sequence divergence are 40%. |

|

|

(1) 滨海生态系统拥有多种不同的生态类型,是微生物研究的良好对象。目前已有针对滨海深古菌的分布及生理生化功能的研究,并取得了一定的成果,但是还有很多研究空白需要填补,包括深古菌的完整代谢途径、各个亚群的分布规律、深古菌在整个生态系统中的作用以及它们对于近海物质循环和能量流通的影响等。这些问题还需要研究者们深入探索。

(2) 目前对于滨海深古菌的研究还只局限在河口和近岸海底这两个生境,对于其它类型生境,包括红树林湿地等生态系统尚未涉足。但红树林湿地等其他生态系统有着与河口、海水所不具有的特征,为发现深古菌独特生活方式或代谢途径提供了一个新可能。

(3) 由于缺少对深古菌成功培养的案例,限制了研究者们对深古菌生理生化机制、遗传特性和生态功能等的研究,对其培养方法的探索也将是深古菌门研究的一个重要方向。

| [1] | Woese CR, Kandler O, Wheelis ML. Towards a natural system of organisms: proposal for the domains Archaea, Bacteria, and Eucarya[J]. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 1990, 87(12) : 4576–4579. DOI:10.1073/pnas.87.12.4576 |

| [2] | Huber H, Hohn MJ, Rachel R, et al. A new phylum of Archaea represented by a nanosized hyperthermophilic symbiont[J]. Nature, 2002, 417(6884) : 63–67. DOI:10.1038/417063a |

| [3] | Brochier-Armanet C, Boussau B, Gribaldo S, et al. Mesophilic Crenarchaeota: proposal for a third archaeal phylum, the Thaumarchaeota[J]. Nature Reviews Microbiology, 2008, 6(3) : 245–252. DOI:10.1038/nrmicro1852 |

| [4] | Barns SM, Delwiche CF, Palmer JD, et al. Perspectives on archaeal diversity, thermophily and monophyly from environmental rRNA sequences[J]. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 1996, 93(17) : 9188–9193. DOI:10.1073/pnas.93.17.9188 |

| [5] | Nunoura T, Takaki Y, Kakuta J, et al. Insights into the evolution of Archaea and eukaryotic protein modifier systems revealed by the genome of a novel archaeal group[J]. Nucleic Acids Research, 2011, 39(8) : 3204–3223. DOI:10.1093/nar/gkq1228 |

| [6] | Baker BJ, Comolli LR, Dick GJ, et al. Enigmatic, ultrasmall, uncultivated Archaea[J]. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 2010, 107(19) : 8806–8811. DOI:10.1073/pnas.0914470107 |

| [7] | Meng J, Xu J, Qin D, et al. Genetic and functional properties of uncultivated MCG archaea assessed by metagenome and gene expression analyses[J]. The ISME Journal, 2014, 8(3) : 650–659. DOI:10.1038/ismej.2013.174 |

| [8] | Spang A, Saw JH, Jørgensen SL, et al. Complex archaea that bridge the gap between prokaryotes and eukaryotes[J]. Nature, 2015, 521(7551) : 173–179. DOI:10.1038/nature14447 |

| [9] | Seitz KW, Lazar CS, Hinrichs KU, et al. Genomic reconstruction of a novel, deeply branched sediment archaeal phylum with pathways for acetogenesis and sulfur reduction[J]. The ISME Journal, 2016, 10(7) : 1696–1705. DOI:10.1038/ismej.2015.233 |

| [10] | Castelle CJ, Wrighton KC, Thomas BC, et al. Genomic expansion of domain archaea highlights roles for organisms from new phyla in anaerobic carbon cycling[J]. Current Biology, 2015, 25(6) : 690–701. DOI:10.1016/j.cub.2015.01.014 |

| [11] | Vanwonterghem I, Evans PN, Parks DH, et al. Methylotrophic methanogenesis discovered in the archaeal phylum Verstraetearchaeota[J]. Nature Microbiology, 2016, 1 : 16170. DOI:10.1038/nmicrobiol.2016.170 |

| [12] | Zaremba-Niedzwiedzka K, Caceres EF, Saw JH, et al. Asgard archaea illuminate the origin of eukaryotic cellular complexity[J]. Nature, 2017, 541(7637) : 353–358. DOI:10.1038/nature21031 |

| [13] | Takai S, Henton MM, Picard JA, et al. Prevalence of virulent Rhodococcus equi in isolates from soil collected from two horse farms in South Africa and restriction fragment length polymorphisms of virulence plasmids in the isolates from infected foals, a dog and a monkey[J]. Onderstepoort Journal of Veterinary Research, 2001, 68(2) : 105–110. |

| [14] | Inagaki F, Suzuki M, Takai K, et al. Microbial communities associated with geological horizons in coastal subseafloor sediments from the sea of Okhotsk[J]. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 2003, 69(12) : 7224–7235. DOI:10.1128/AEM.69.12.7224-7235.2003 |

| [15] | Li PY, Xie BB, Zhang XY, et al. Genetic structure of three fosmid-fragments encoding 16S rRNA genes of the Miscellaneous Crenarchaeotic Group (MCG): implications for physiology and evolution of marine sedimentary archaea[J]. Environmental Microbiology, 2012, 14(2) : 467–479. DOI:10.1111/j.1462-2920.2011.02637.x |

| [16] | Kubo K, Lloyd KG, Biddle JF, et al. Archaea of the Miscellaneous Crenarchaeotal Group are abundant, diverse and widespread in marine sediments[J]. The ISME Journal, 2012, 6(10) : 1949–1965. DOI:10.1038/ismej.2012.37 |

| [17] | Lloyd KG, Schreiber L, Petersen DG, et al. Predominant archaea in marine sediments degrade detrital proteins[J]. Nature, 2013, 496(7444) : 215–218. DOI:10.1038/nature12033 |

| [18] | Biddle JF, Lipp JS, Lever MA, et al. Heterotrophic Archaea dominate sedimentary subsurface ecosystems off Peru[J]. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 2006, 103(10) : 3846–3851. DOI:10.1073/pnas.0600035103 |

| [19] | Webster G, Rinna J, Roussel EG, et al. Prokaryotic functional diversity in different biogeochemical depth zones in tidal sediments of the Severn Estuary, UK, revealed by stable-isotope probing[J]. FEMS Microbiology Ecology, 2010, 72(2) : 179–197. DOI:10.1111/fem.2010.72.issue-2 |

| [20] | Seyler LM, McGuinness LM, Kerkhof LJ. Crenarchaeal heterotrophy in salt marsh sediments[J]. The ISME Journal, 2014, 8(7) : 1534–1543. DOI:10.1038/ismej.2014.15 |

| [21] | Evans PN, Parks DH, Chadwick GL, et al. Methane metabolism in the archaeal phylum Bathyarchaeota revealed by genome-centric metagenomics[J]. Science, 2015, 350(6259) : 434–438. DOI:10.1126/science.aac7745 |

| [22] | He Y, Li M, Perumal V, et al. Genomic and enzymatic evidence for acetogenesis among multiple lineages of the archaeal phylum Bathyarchaeota widespread in marine sediments[J]. Nature Microbiology, 2016, 1(6) : 16035. DOI:10.1038/nmicrobiol.2016.35 |

| [23] | Lazar CS, Baker BJ, Seitz K, et al. Genomic evidence for distinct carbon substrate preferences and ecological niches of Bathyarchaeota in estuarine sediments[J]. Environmental Microbiology, 2016, 18(4) : 1200–1211. DOI:10.1111/emi.2016.18.issue-4 |

| [24] | Meador TB, Bowles MW, Lazar CS, et al. The archaeal lipidome in estuarine sediment dominated by members of the Miscellaneous Crenarchaeotal Group[J]. Environmental Microbiology, 2015, 17(7) : 2441–2458. DOI:10.1111/1462-2920.12716 |

| [25] | Zhang WP, Ding W, Yang B, et al. Genomic and transcriptomic evidence for carbohydrate consumption among microorganisms in a cold seep brine pool[J]. Frontiers in Microbiology, 2016, 7 : 1825. |

| [26] | Coolen MJL, Cypionka H, Sass AM, et al. Ongoing modification of Mediterranean Pleistocene sapropels mediated by prokaryotes[J]. Science, 2002, 296(5577) : 2407–2410. DOI:10.1126/science.1071893 |

| [27] | Inagaki F, Nunoura T, Nakagawa S, et al. Biogeographical distribution and diversity of microbes in methane hydrate-bearing deep marine sediments on the Pacific Ocean Margin[J]. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 2006, 103(8) : 2815–2820. DOI:10.1073/pnas.0511033103 |

| [28] | Newberry CJ, Webster G, Cragg BA, et al. Diversity of prokaryotes and methanogenesis in deep subsurface sediments from the Nankai Trough, Ocean Drilling Program Leg 190[J]. Environmental Microbiology, 2004, 6(3) : 274–287. DOI:10.1111/emi.2004.6.issue-3 |

| [29] | Parkes RJ, Webster G, Cragg BA, et al. Deep sub-seafloor prokaryotes stimulated at interfaces over geological time[J]. Nature, 2005, 436(7049) : 390–394. DOI:10.1038/nature03796 |

| [30] | Reed DW, Fujita Y, Delwiche ME, et al. Microbial communities from methane hydrate-bearing deep marine sediments in a forearc basin[J]. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 2002, 68(8) : 3759–3770. DOI:10.1128/AEM.68.8.3759-3770.2002 |

| [31] | Teske AP. Microbial communities of deep marine subsurface sediments: molecular and cultivation surveys[J]. Geomicrobiology Journal, 2006, 23(6) : 357–368. DOI:10.1080/01490450600875613 |

| [32] | Fry JC, Parkes RJ, Cragg BA, et al. Prokaryotic biodiversity and activity in the deep subseafloor biosphere[J]. FEMS Microbiology Ecology, 2008, 66(2) : 181–196. DOI:10.1111/fem.2008.66.issue-2 |

| [33] | Lazar CS, Biddle JF, Meador TB, et al. Environmental controls on intragroup diversity of the uncultured benthic archaea of the miscellaneous Crenarchaeotal group lineage naturally enriched in anoxic sediments of the White Oak River estuary (North Carolina, USA)[J]. Environmental Microbiology, 2015, 17(7) : 2228–2238. DOI:10.1111/1462-2920.12659 |

| [34] | Sørensen KB, Teske A. Stratified communities of active archaea in deep marine subsurface sediments[J]. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 2006, 72(7) : 4596–4603. DOI:10.1128/AEM.00562-06 |

| [35] | Jiang LJ, Zheng YP, Chen JQ, et al. Stratification of Archaeal communities in shallow sediments of the Pearl River Estuary, Southern China[J]. Antonie van Leeuwenhoek, 2011, 99(4) : 739–751. DOI:10.1007/s10482-011-9548-3 |

| [36] | Fillol M, Sànchez-Melsió A, Gich F, et al. Diversity of Miscellaneous Crenarchaeotic Group archaea in freshwater karstic lakes and their segregation between planktonic and sediment habitats[J]. FEMS Microbiology Ecology, 2015, 91(4) : fiv020. |

| [37] | Sogin ML, Morrison HG, Huber JA, et al. Microbial diversity in the deep sea and the underexplored "rare biosphere"[J]. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 2006, 103(32) : 12115–12120. DOI:10.1073/pnas.0605127103 |

| [38] | Fillol M, Auguet JC, Casamayor EO, et al. Insights in the ecology and evolutionary history of the Miscellaneous Crenarchaeotic Group lineage[J]. The ISME Journal, 2016, 10(3) : 665–677. DOI:10.1038/ismej.2015.143 |

| [39] | Xiang X, Wang RC, Wang HM, et al. Distribution of bathyarchaeota communities across different terrestrial settings and their potential ecological functions[J]. Scientific Reports, 2017, 7 : 45028. DOI:10.1038/srep45028 |

| [40] | Martínez ML, Intralawan A, Vázquez G, et al. The coasts of our world: ecological, economic and social importance[J]. Ecological Economics, 2007, 63(2/3) : 254–272. |

| [41] | Liu JW, Yang HM, Zhao MX, et al. Spatial distribution patterns of benthic microbial communities along the Pearl Estuary, China[J]. Systematic and Applied Microbiology, 2014, 37(8) : 578–589. DOI:10.1016/j.syapm.2014.10.005 |

| [42] | Yan B, Hong K, Yu ZN. Archaeal communities in mangrove soil characterized by 16S rRNA gene clones[J]. Journal of Microbiology, 2006, 44(5) : 566–571. |

| [43] | Zhang XY, Xu J, Xiao J, et al. Archaeal lineages detected in mangrove sediment in the Zhangjiang estuary of Fujian province[J]. Journal of Shandong University (Natural Science), 2009, 44(3) : 1–6, 10. (in Chinese) 张熙颖, 许静, 肖静, 等. 福建漳江口红树林沉积物中的古菌类群[J]. 山东大学学报:理学版, 2009, 44(3) : 1–6, 10. |

2017, Vol. 44

2017, Vol. 44