扩展功能

文章信息

- 周昌娈, 谭磊, 丁铲

- ZHOU Chang-Luan, TAN Lei, DING Chan

- RNA病毒利用外泌体促进病毒感染的研究进展

- Advances of RNA virus increasing viral infection through the exosomes

- 微生物学通报, 2017, 44(12): 2988-2996

- Microbiology China, 2017, 44(12): 2988-2996

- DOI: 10.13344/j.microbiol.china.170390

-

文章历史

- 收稿日期: 2017-06-02

- 接受日期: 2017-10-30

- 优先数字出版日期(www.cnki.net): 2017-10-30

Harding等于1983年首次在绵羊网织红细胞培养上清中发现了一些囊泡[1]。1986年,Johnstone等认为这些囊泡似乎正进行着“反内吞”作用而将其命名为“Exosome”,中文名译为“外泌体”[2]。不同于细胞常见的胞吐作用,细胞分泌的外泌体是一种具有典型的脂质双分子层结构、直径约为30-100 nm的囊泡,浮密度约1.13-1.19 g/mL。几乎所有类型的细胞都可以分泌外泌体,所有体液中都存在外泌体。在外泌体被发现的最初几年,人们一直认为其可能是作为细胞排除废物的“垃圾包”而被细胞主动分泌到胞外。近年来,随着发现外泌体可以作为旁分泌、自分泌、内分泌、细胞与细胞直接接触之外的另一种特别而重要的细胞间通讯方式,而受到重视。因其能转运活性蛋白、脂质和RNA,在病毒感染中发挥着不可或缺的作用。不同类型细胞分泌的外泌体以及处于不同生理状态的细胞分泌的外泌体、外泌体中的各种成分等,对于病毒复制及其致病机制的影响也不尽相同。若干病毒已根据外泌体的生物学特性及功能进化出一些利用策略,来逃避宿主的免疫系统[3-4],促进自身感染。目前,外泌体的相关研究受到重视,但仍有许多空白有待填补,如外泌体在不同病毒感染中发挥何样作用,是如何发挥作用等。较之DNA病毒,有囊膜RNA病毒与外泌体有相似之处,并能劫持外泌体助其扩散感染,使得两者之间的关系更富挑战性。因此,本文着眼于RNA病毒,首先简要介绍外泌体的组成与生成,并选取几个研究较清楚的RNA病毒,重点阐述了外泌体如何促进这些RNA病毒感染,归纳了迄今已发现的外泌体在病毒感染中的可能作用机制,为大家进一步了解外泌体与病毒感染之间的关系提供帮助。

1 外泌体的组成与生成 1.1 外泌体的组成成分外泌体的组成极其丰富,目前主要分为三大类:蛋白质、mRNA和microRNA。多个数据库可以为外泌体研究提供丰富的数据资源,如EVPedia[5],Vesiclepedia[6]和ExoCarta[7]等。至今,根据ExoCarta统计,已发现外泌体中含有9 769种蛋白质、3 408种mRNA和2 838种microRNA。除此之外,ExoCarta还显示现已发现1 116种脂类也能进入外泌体。

不同细胞分泌的外泌体表面具有一些共同的标记蛋白,如热休克蛋白70 (70 kilodalton heat shock proteins,HSP70)和热休克蛋白90 (90 kilodalton heat shock proteins,HSP90),四跨膜蛋白CD9、CD63、CD81和CD82等。其它参与囊膜形成而被外泌体捕获的宿主蛋白,如凋亡相关基因(Apoptosis linked gene,ALG)和肿瘤易感基因101 (Tumor susceptibility gene 101,TSG101) [8]等也被纳入外泌体中。这些蛋白也可以作为标志物鉴别外泌体。值得注意的是,病毒感染细胞后这些蛋白的含量可能会发生变化,如TSG101、CD63。外泌体内容物的差别主要取决于细胞类型及细胞所处的生理及病理状态,往往细胞的状态与外泌体功能相关,这表明招募核酸和蛋白进入外泌体是一个可调控的过程,而恰恰正是这一点存在着重要的生物学意义!

1.2 外泌体的生成过程目前外泌体的生成与内容物分拣机制仍未得到很好的解释。一般认为细胞经内吞作用形成早期核内体,待其中的管腔内泡(Intraluminal vesicles,ILVs)生成后,早期核内体成熟为晚期核内体,即多胞体(Multivesicular bodies,MVBs)。部分未被溶酶体降解的MVBs与细胞质膜融合,生成外泌体[4]。此过程需要内体分选转运复合物(Endosomal sorting complex required for transport,ESCRT),因为核内体需要ESCRT-0将分拣的复合物传递MVBs[9],同时将ESCRT-I募集至核内体膜上[10],而ESCRT-I反过来募集ESCRT-Ⅱ和ESCRT-Ⅲ[11]。ESCRT-Ⅲ能介导高分子纤维的生成,致使膜内陷,最终生成ILVs。但也有一些研究表明,外泌体生成与释放可以不依赖于ESCRT,如脂质神经酰胺可调节少突神经胶质细胞外泌体的生成等[12]。最近报道的CD63跨膜蛋白可以介导外泌体内容物分拣和ILVs的形成,而不依赖于ESCRT和脂质神经酰胺[13]。因此,现在很多研究认为外泌体的生成机制是多样的,而且具有细胞的特异性。

2 RNA病毒与外泌体的相似性及差异性越来越多的报道发现,外泌体在多个方面与RNA病毒具有相似特性,尤其是逆转录病毒:首先,一般外泌体直径约在100 nm,很多RNA病毒也处于此范围内;与囊膜病毒类似,外泌体也具有包含膜蛋白的双层脂质膜;目前大部分发现的外泌体像许多病毒一样,形成于核内体系统,如依赖于ESCRT机制,且出芽位置与病毒相同;外泌体像病毒一样,能结合周边邻近或全身各种细胞的细胞膜,以融合或内吞方式进入并引发这些细胞的特异反应。最后,外泌体也能携带遗传物质,甚至包含整个病毒颗粒,改变受体细胞的功能。

然而,20世纪病毒学家将病毒定义为一种只能存活于活细胞内并具有感染性的微生物。外泌体不属于此范畴,因其不具备复制能力。但随着当代病毒学对“非感染性病毒”和“缺陷病毒”定义的广泛认知,病毒感染细胞释放出的外泌体因其有时携带有病毒核酸或病毒蛋白,与失去复制能力的非感染性缺陷病毒极其相似,无论从形态学还是生物学功能上很难将两者完全区分开,甚至有人提出外泌体应属于非感染性病毒范畴[14]。

3 外泌体促进RNA病毒感染宿主细胞分泌的外泌体主要通过两种机制促进RNA病毒感染:一是病毒组分包装、整合入外泌体以实现细胞间传播;二是病毒劫持外泌体,实现免疫逃避。

3.1 外泌体携带RNA病毒组分促进病毒感染目前对部分RNA病毒研究发现,RNA病毒感染细胞释放出的外泌体中包含病毒核酸、病毒蛋白和脂质等。

3.1.1 HIV: HIV-1是首个被用于外泌体研究的RNA病毒,也是目前研究最多最深入的病毒之一。目前已发现存在于外泌体中的HIV病毒组分有:负调控因子(Negative regulatory factor,Nef) mRNA[15]和反式激活反应元件(Transactivation response element,TAR) RNA[16];病毒microRNA vmiR88、vmi99和vmiR-TAR[17],C-C趋化因子受体5 (C-C chemokine receptor type 5,CCR5) [18]和C-X-C趋化因子受体4 (C-X-C chemokine receptor type 4,CXCR4) [19];Nef蛋白[15]和群特异性抗原(Group-specific antigen,Gag)蛋白[20];未剪切的HIV-1 mRNA[20]等(表 1)。| 科 Classfication | 病毒 Virus | 活性成分 Active components | 促进病毒复制机制 Mechanism of promoting virus replication | 参考文献 References |

| Retroviridae | HIV | Nef mRNA | Inducing the expression of A beta | [15] |

| Nef protein | Inducing apoptosis in T cells and inhibiting RNA interference | [15] | ||

| TAR RNA | Recruiting elongation factor and inhibiting apoptosis | [16] | ||

| VmiR-88 | Stimulating TNF alpha release | [17] | ||

| VmiR-99 | [17] | |||

| VmiR-TAR | Silencing Bcl-2 interacting protein mRNA and inhibiting apoptosis | [17] | ||

| CCR5 | Increasing the types of susceptible cells | [18] | ||

| CXCR4 | [19] | |||

| Gag protein | Promoting viral budding | [20] | ||

| Genome RNA | Helping virus particles unable assembled in cells | [20] | ||

| HTLV-1 | Tax protein | Inhibiting apoptosis of recipient cells and improving survival rate of the cells | [21] | |

| Tax mRNA | [21] | |||

| HBZ mRNA | Promoting the proliferation of recipient cells | [21] | ||

| Env mRNA | Promoting the fusion with target cells | [21] | ||

| Flaviviridae | HCV | Genome RNA | Promoting the transmission of viruses in hepatocytes | [22] |

| Antisense RNA | Related to RNA interference silencing | [23] | ||

| Core protein | Promoting viral release and assembly | [24] | ||

| NS5A | [25] | |||

| HGV | HGV RNA | Achieving persistent infection | [26] | |

| Filoviridae | Ebola | VP40 | Promoting cell apoptosis | [27] |

| Picornaviridae | EV71 | EV71 RNA | Spreading between different kinds of cells | [28] |

| VP1 | Achieving persistent infection | [28] | ||

| Bunyaviridae | RVFV | Genome RNA | Transferring directly to recipient cells | [29] |

Nef,即HIV辅助蛋白阴性因子,是HIV-1重要的毒力因子,HIV-I感染细胞培养上清外泌体及HIV病人血浆外泌体中都能检测到Nef蛋白。Nef分泌调节区与Hsp70家族成员线粒体热休克蛋白70 (Mitochondrial 70 kD heat shock protein,mtHsp70)相互作用,将Nef选择性地整合入外泌体中。Nef蛋白可以通过外泌体激活静息CD4+ T细胞,增加对HIV的易感性,扩大HIV传播,促进HIV复制,这也在一定程度上解释了HIV感染早期T细胞大量死亡的原因,可能也是感染初期病毒在器官内大量传播的机制之一[30]。再者,Nef能与Ago-2 (Argonaute-2)结合,抑制影响病毒复制的RNA干扰作用[31],调节外泌体中microRNA的组成。这进一步暗示了外泌体在HIV致病及复制中的作用。除了Nef蛋白,Nef mRNA也被整合进入外泌体内。但也有报道认为,外泌体可能不参与转运Nef,Nef具有膜靶向功能,其转运可能依赖于细胞间的直接接触[32]。用HIV感染Jurkat细胞或表达Nef的Jurkat和293T细胞分泌的外泌体孵育靶细胞Jurkat检测不到Nef,且细胞内外Nef电镜形态差异不显著。

TAR RNA位于HIV mRNA 5′端,是由52个碱基组成的RNA茎环结构。在外泌体中已发现了TAR RNA及由其加工而成的病毒microRNA、vmiR-TAR,前者与Tat结合,有利于募集延伸因子,提高病毒RNA的产量,同时降低受体细胞中B细胞淋巴瘤/白血病-2蛋白(B-cell lymphoma-2,Bcl-2)促凋亡蛋白(Bcl-2 interacting mediator of cell death,Bim)和周期蛋白依赖性激酶9 (Cyclin-dependent kinase 9,Cdk9)蛋白水平,下调凋亡;后者作为HIV-1含量最丰富的病毒microRNA,沉默Bcl-2互作蛋白mRNA,阻止感染细胞凋亡,增加易感细胞数量,延长病毒潜伏期,以产生更多的病毒,从而利于病毒感染。

目前在外泌体中只发现了未剪切的HIV-1全长RNA。较受体细胞,外泌体容载能力小,缺乏逆转录的必备成分,因此基因组RNA进入外泌体不是通过感染,而是经由包装整合。当细胞不能进行病毒基因组包装时,HIV-1基因组RNA整合进入外泌体的数量就会明显增加,这也从侧面反应了包装进入外泌体可以作为病毒解决宿主细胞内组装问题的方式之一。

HIV编码的vmiR88和vmiR99能刺激巨噬细胞的信号通路,促进前炎症细胞因子如TNF-α等从巨噬细胞大量释放,有利于获得性免疫缺乏综合征(Acquired immunodeficiency syndrome,AIDs)致病性的产生。体外实验中,外泌体将HIV辅助受体CCR5和CXCR4传递给无辅助受体的细胞,允许HIV-1进入细胞,增强细胞对病毒的亲和力,扩宽病毒感染细胞的种类,使病毒在非感染细胞中也易于扩散。但该现象是否也发生在体内,目前还不得而知。

外泌体吸收病毒颗粒,是一种不依赖于病毒受体,也不依赖于囊膜的病毒感染模式。未成熟的树突状细胞(Dendritic cells,DCs)细胞能捕捉HIV-1颗粒,并将其递呈给T细胞,实现HIV转移感染。包装进入外泌体的病毒颗粒占外排病毒颗粒的主体,这说明外泌体能促成病毒在不同类型细胞间传递。然而,对于外泌体传递HIV-1颗粒,如今仍有争议,因为病毒出芽位置与外泌体生成位置相同。

3.1.2 HTLV: 2014年Jaworski等发现,人类T淋巴细胞白血病1型病毒(Human T-lymphotropic virus type 1,HTLV-1)感染细胞分泌的外泌体里包含有HTLV Tax蛋白和HTLV Tax mRNA、HBZ mRNA、Env mRNA[21] (表 1)。HTLV-1转录激活蛋白Tax能调节多个重要的胞内通路,如宿主细胞DNA损伤反应机制,细胞周期和凋亡。游离的Tax蛋白能诱导DC细胞分泌白介素10 (Interleukin 10,IL-10)、白介素12 (Interleukin 12,IL-12)、白介素17A (Interleukin 17A,IL-17A)、γ干扰素(Interferon,IFN-γ)和粒细胞集落刺激因子(Granulocyte-colony stimulating factor,G-CSF)等细胞因子。而C81细胞释放载有Tax蛋白的外泌体,与DC细胞共孵育后,DC中的白介素2 (Interleukin 2,IL-2)、白介素5 (Interleukin 5,IL-5)、白介素6 (Interleukin 6,IL-6)水平显著上调[33]。外泌体捕捉HTLV-1病毒蛋白的机制还未能得到很好的解释。总之,这些发现说明外泌体在HTLV-1蛋白和mRNA胞外传递给受体细胞的过程中起重要作用。与HIV-1不同,HTLV-1感染细胞释放的外泌体鲜有病毒microRNA,但与宿主microRNA结合的Ago水平上升,可能是由于HTLV-1感染分泌的外泌体能快速调节受体细胞中的mRNA,并抑制其表达。

3.1.3 HCV: 已在外泌体中发现了完整的丙型肝炎病毒(Hepatitis C virus,HCV)基因组[22],具有复制能力的反义RNA[23]、HCV核蛋白[24]、非结构蛋白5A (Non-structural protein 5A,NS5A)[25] (表 1)。利用HCV亚基因复制子细胞分泌的外泌体能不依赖于病毒受体,不需要病毒组装,而将具有复制能力的HCV RNA运至易感细胞,实现持续性感染[34]。目前外泌体吸收HCV全长RNA的机制仍未知,这似乎是一个主动的过程,因为HCV RNA较甘油醛-3-磷酸脱氢酶(Glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase,GAPDH) mRNA丰度超1 000倍左右。而外泌体中的HCV反义RNA,与Ago2、Hsp90和miR-122相关联[35]。近期证明,miR-122和Ago2通过与HCV双链RNA 5′非翻译区(Untranslated Region,UTR)结合,的确能增强HCV复制[36]。对于是否所有的病毒感染的外泌体都含有Ago2、Hsp90和miR-122等这些有利于病毒复制的共因子,仍有待研究。HCV NS5A在病毒RNA复制与病毒组装中起双重作用。HCV NS5A与外泌体途径相关,有利于HCV自然感染[25]。四跨膜蛋白CD81,不仅是外泌体的标记蛋白之一,也是HCV进入细胞的病毒受体。它能与E2结合,有利于外泌体在胞内胞间捕捉E2。HCV基因组和CD81-E2复合物出细胞进入外泌体,利用外泌体的膜融合功能感染细胞。但事实上,外泌体传递HCV病毒颗粒是不依赖于经典的E1/E2病毒糖蛋白受体途径进入细胞的。

3.1.4 其他RNA病毒: 携带庚型肝炎病毒(Hepatitis G virus,HGV) RNA的外泌体在感染血清中被分离到,并在体外被转运至外周血液单核细胞中,造成持续性感染[26]。埃博拉病毒(Ebola virus,EBOV)结构蛋白VP40也被发现包装进入外泌体,这可能是T细胞失常和淋巴细胞凋亡的原因之一,促使EBOV在免疫功能受损伤的宿主体内大量复制[27]。肠道病毒71型(Human enterovirus 71,EV71) RNA与核衣壳蛋白VP1在EV71感染横纹肌肉瘤细胞分泌的外泌体中被检测到[28]。这些包含病毒成分的外泌体可实现EV71在人神经母细胞瘤SK-NLSH细胞株的持续性感染,并能抵抗中和抗体,说明外泌体在EV71传播中起重要作用。裂谷热病毒(Rift Valley fever virus,RVFV)感染Vero细胞分泌的外泌体也发现包含病毒基因组RNA,并传递给受体细胞[29]。 3.2 外泌体帮助病毒逃逸宿主免疫的可能机制目前,RNA病毒利用外泌体逃逸宿主免疫系统的具体机制仍未完全破解,现发现有几种可能机制。

首先,RNA病毒经外泌体传递病毒蛋白,实现免疫逃逸,如出现于外泌体中的HIV Nef蛋白,它能与CD4受体和MHC-Ⅰ分子胞浆尾区结合,通过细胞内吞作用转运至溶酶体,降解CD4和MHC-Ⅰ分子[31],逃逸宿主免疫。同时巨噬细胞中的Nef蛋白也可经外泌体传递,抑制B细胞内IgG2和IgA的产生[37]。

有些无囊膜RNA病毒依赖于生成外泌体的ESCRT通路,将外泌体的双层膜作为后天获得的囊膜抵御宿主抗体中和,同时也作为病毒潜伏的藏毒库逃逸宿主免疫识别,甲型肝炎病毒(Hepatitis A virus,HAV)就是一典型案例。在核内体中发现的HAV核衣壳VP2与ESCRT-Ⅲ两种组分Alix、VPS4B相互作用,生成有囊膜的HAV病毒颗粒[38]。含HAV病毒颗粒的外泌体,又称囊膜甲型肝炎病毒(Enveloped Hepatitis A virus,eHAV),不同于HAV和eHAV这种隐形病毒不仅完全具有感染性,而且能完全抵抗中和抗体,这也在一定程度上解释了HAV患者体内为何在感染3-4周后才出现病毒特异性抗体。HAV囊膜化的发现,也对根据有无囊膜分类病毒的原则提出了挑战[39]。同时Liu等利用电镜观察发现,外泌体将HCV传递给未感染细胞,也能在某种程度上抑制HCV中和抗体[40]。

巧妙地利用外泌体转运microRNA,也是病毒逃逸免疫的策略之一。当病毒进入潜伏期后,有人认为由于免疫系统无法识别microRNA,病毒便趁机利用外泌体向周围释放microRNA,使邻近细胞更易感,待有信号触发病毒复制后,加速病毒感染[41]。除了RNA病毒本身组分及相关产物,还发现一些分子能抑制免疫反应,Esser等在HIV-I感染细胞所释放的外泌体中发现了一系列蛋白,如CD86、CD45和MHC Ⅱ类分子,通过抑制免疫反应帮助病毒复制[42]。

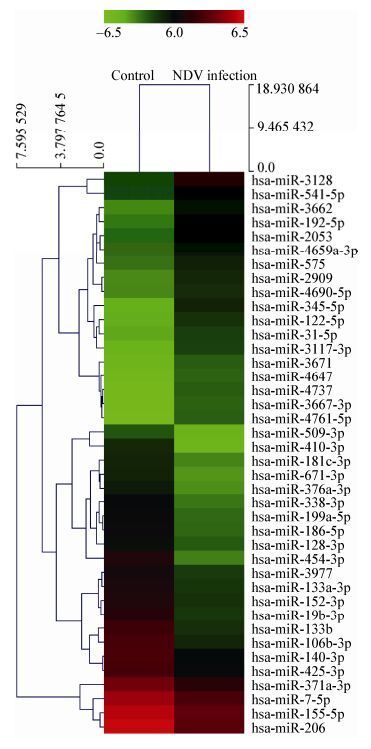

目前在家禽病毒方面外泌体研究较少,新城疫病毒(Newcastle disease virus,NDV)与外泌体也未有报道,我们实验室从事新城疫病毒研究数十年[43-45],利用microRNA芯片分析发现,NDV感染细胞分泌的外泌体中,260种microRNA发生两倍以上的表达变化,其中154个表达上调(图 1,表 2)。

|

| 图 1 外泌体microRNA表达变化的热力聚类图 Figure 1 Two-way hierarchical cluster heat map of exosomal microRNAs profile 注:该图仅展示NDV感染HeLa细胞分泌的外泌体中表达水平发生5倍以上变化的microRNA. Note: This figure merely showed exosomal microRNAs from HeLa cell infected by NDV with more than 5 times expression level. |

|

|

| 名称 Name | 调节 Regulation | 倍数 Fold change | 名称 Name | 趋势 Differential expression | 倍数 Fold change |

| hsa-miR-3128 | Up | 12.926 | hsa-miR-133a-3p | Down | 0.187 |

| hsa-miR-3662 | Up | 11.250 | hsa-miR-425-3p | Down | 0.186 |

| hsa-miR-4761-5p | Up | 9.323 | hsa-miR-155-5p | Down | 0.182 |

| hsa-miR-192-5p | Up | 9.081 | hsa-miR-152-3p | Down | 0.181 |

| hsa-miR-122-5p | Up | 9.064 | hsa-miR-371a-3p | Down | 0.178 |

| hsa-miR-4737 | Up | 8.668 | hsa-miR-509-3p | Down | 0.170 |

| hsa-miR-3117-3p | Up | 8.550 | hsa-miR-140-3p | Down | 0.167 |

| hsa-miR-3667-3p | Up | 7.776 | hsa-miR-181c-3p | Down | 0.157 |

| hsa-miR-2053 | Up | 7.484 | hsa-miR-19b-3p | Down | 0.132 |

| hsa-miR-4647 | Up | 6.798 | hsa-miR-206 | Down | 0.128 |

| hsa-miR-3671 | Up | 6.304 | hsa-miR-671-3p | Down | 0.114 |

| hsa-miR-2909 | Up | 6.242 | hsa-miR-199a-5p | Down | 0.112 |

| hsa-miR-4659a-3p | Up | 6.174 | hsa-miR-338-3p | Down | 0.106 |

| hsa-miR-31-5p | Up | 5.966 | hsa-miR-186-5p | Down | 0.103 |

| hsa-miR-4690-5p | Up | 5.249 | hsa-miR-376a-3p | Down | 0.100 |

| hsa-miR-575 | Up | 5.161 | hsa-miR-106b-3p | Down | 0.085 |

| hsa-miR-541-5p | Up | 5.099 | hsa-miR-133b | Down | 0.084 |

| hsa-miR-7-5p | Down | 0.195 | hsa-miR-410-3p | Down | 0.058 |

| hsa-miR-3977 | Down | 0.195 | hsa-miR-454-3p | Down | 0.043 |

| hsa-miR-128-3p | Down | 0.193 | |||

| 注:该图仅展示NDV感染HeLa细胞分泌的外泌体中表达水平发生5倍以上变化的microRNA. Note: This figure merely shows exosomal microRNA from HeLa cell infected by NDV with more than 5 times expression level. | |||||

我们的初步研究发现,这些上调的microRNA中有一些是特异性抑制先天性免疫分子I型干扰素mRNA的表达,有利于病毒的复制和感染的扩散。

4 小结外泌体宛如一位使者,在不同细胞中往来,交换生物信息。不同细胞来源的外泌体携带的信息也不尽相同,它们像远行的移民,似乎总残存着家乡的印记,或多或少地影响着受体细胞。病毒的入侵往往又改变了外泌体的内容,犹如一种夹带了危险品的邮包被送到胞外,再由其制造危险,这是一次黑化,为宿主细胞服务的外泌体再经历病毒感染后,携带有病毒组分或受病毒调节后的细胞组分,助其逃逸宿主免疫,促进病毒感染复制。当然,也有外泌体仍然是正义的使者,它们能坚持激活宿主免疫反应,帮助宿主抵御外来入侵者病毒的感染,即使随着病毒感染进程的发展,它们的数量会越来越少。

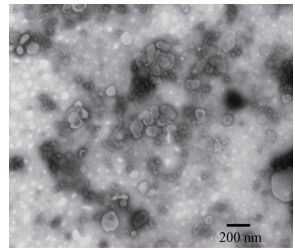

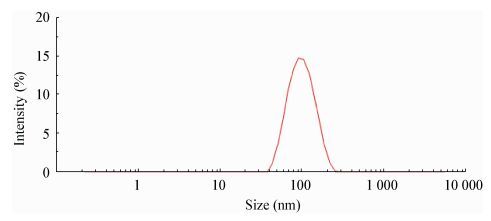

然而,这其中仍有大量黑匣子区域未曾知晓,外泌体领域的大片空白等待研究者去填补。得到高纯度的外泌体是开展外泌体研究的重要前提,考虑到新城疫病毒的血凝性,我们用新鲜鸡红细胞吸附细胞上清样品,去除了与外泌体颗粒大小差异不大的病毒粒子,纯化了外泌体,经电镜(图 2)及Nanosight (图 3)测试获得大小约为93.81±33.81 nm的外泌体。

|

| 图 2 NDV感染后HeLa细胞分泌的外泌体电镜图 Figure 2 Electron micrograph of exosomes secreted by HeLa cell after NDV infection 注:外泌体来源于NDV感染的HeLa细胞. Notes: These exosomes were from HeLa cell infected by NDV. |

|

|

|

| 图 3 外泌体纳米颗粒捕捉技术分析 Figure 3 Nanoparticles tracking analysis for exosomes secreted by HeLa cell after NDV infection 注:外泌体来源于NDV感染的HeLa细胞. Notes: These exosomes were from HeLa cell infected by NDV. |

|

|

同时在新城疫病毒与外泌体实验中,我们发现比较相同体积的新城疫病毒感染及鸡马克立病毒感染细胞的上清中,新城疫强毒株Herts/33感染细胞分泌的外泌体较少,这也提出了一系列问题:为什么慢性感染产生的外泌体较多?是否烈性感染产生的外泌体少?是否与宿主细胞应激状态相关?而经病毒刺激产生的大量外泌体是宿主的朋友还是病毒的帮凶?在新城疫病毒感染细胞分泌的外泌体中是否也具有病毒RNA和蛋白,抑或整个病毒颗粒?众所周知,新城疫病毒具有很强的靶向溶瘤性,由其感染细胞产生的外泌体是否促进溶瘤作用?这一系列问题仍有待我们去研究、去寻求答案。

| [1] |

Harding C, Heuser J, Stahl P. Receptor-mediated endocytosis of transferrin and recycling of the transferrin receptor in rat reticulocytes[J]. Journal of Cell Biology, 1983, 97(2): 329-339. DOI:10.1083/jcb.97.2.329 |

| [2] |

Johnstone RM, Adam M, Hammond JR, et al. Vesicle formation during reticulocyte maturation. Association of plasma membrane activities with released vesicles (exosomes)[J]. Journal of Biological Chemistry, 1987, 262(19): 9412-9420. |

| [3] |

Schwab A, Meyering SS, Lepene B, et al. Extracellular vesicles from infected cells: potential for direct pathogenesis[J]. Frontiers in microbiology, 2015, 6: 1132. |

| [4] |

Alenquer M, Amorim MJ. Exosome biogenesis, regulation, and function in viral infection[J]. Viruses, 2015, 7(9): 5066-5083. DOI:10.3390/v7092862 |

| [5] |

Kim DK, Kang B, Kim OY, et al. EVpedia: an integrated database of high-throughput data for systemic analyses of extracellular vesicles[J]. Journal of extracellular Vesicles, 2013, 2(1): 20384. DOI:10.3402/jev.v2i0.20384 |

| [6] |

Kalra H, Simpson RJ, Ji H, et al. Vesiclepedia: a compendium for extracellular vesicles with continuous community annotation[J]. PLoS biology, 2012, 10(12): e1001450. DOI:10.1371/journal.pbio.1001450 |

| [7] |

Keerthikumar S, Chisanga D, Ariyaratne D, et al. ExoCarta: a web-based compendium of exosomal cargo[J]. Journal of Molecular Biology, 2016, 428(4): 688-692. DOI:10.1016/j.jmb.2015.09.019 |

| [8] |

Akers JC, Gonda D, Kim R, et al. Biogenesis of extracellular vesicles (EV): exosomes, microvesicles, retrovirus-like vesicles, and apoptotic bodies[J]. Journal of neuro-oncology, 2013, 113(1): 1-11. DOI:10.1007/s11060-013-1084-8 |

| [9] |

Raiborg C, Stenmark H. Hrs and endocytic sorting of ubiquitinated membrane proteins[J]. Cell Structure & Function, 2002, 27(6): 403-408. |

| [10] |

Katzmann DJ, Babst M, Emr SD. Ubiquitin-dependent sorting into the multivesicular body pathway requires the function of a conserved endosomal protein sorting complex, ESCRT-I[J]. Cell, 2001, 106(2): 145-155. DOI:10.1016/S0092-8674(01)00434-2 |

| [11] |

Babst M, Katzmann DJ, Snyder WB, et al. Endosome-associated complex, ESCRT-Ⅱ, recruits transport machinery for protein sorting at the multivesicular body[J]. Developmental Cell, 2002, 3(2): 283-289. DOI:10.1016/S1534-5807(02)00219-8 |

| [12] |

Trajkovic K, Hsu C, Chiantia S, et al. Ceramide triggers budding of exosome vesicles into multivesicular endosomes[J]. Science, 2008, 319(5867): 1244-1247. DOI:10.1126/science.1153124 |

| [13] |

van Niel G, Charrin S, Simoes S, et al. The tetraspanin CD63 regulates ESCRT-independent and -dependent endosomal sorting during melanogenesis[J]. Developmental Cell, 2011, 21(4): 708-721. DOI:10.1016/j.devcel.2011.08.019 |

| [14] |

Nolte-'t Hoen E, Cremer T, Gallo RC, et al. Extracellular vesicles and viruses: are they close relatives?[J]. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 2016, 113(33): 9155-9161. DOI:10.1073/pnas.1605146113 |

| [15] |

Khan MB, Lang ML, Huang MB, et al. Nef exosomes isolated from the plasma of individuals with HIV-associated dementia (HAD) can induce Aβ1-42 secretion in SH-SY5Y neural cells[J]. Journal of neuro virology, 2016, 22(2): 179-190. |

| [16] |

Narayanan A, Iordanskiy S, Das R, et al. Exosomes derived from HIV-1-infected cells contain trans-activation response element RNA[J]. Journal of biology chemistry, 2013, 288(27): 20014-20033. DOI:10.1074/jbc.M112.438895 |

| [17] |

Bernard MA, Zhao H, Yue SC, et al. Novel HIV-1 miRNAs stimulate TNFα release in human macrophages via TLR8 signaling pathway[J]. PLoS One, 2014, 9(9): e106006. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0106006 |

| [18] |

Mack M, Kleinschmidt A, Brühl H, et al. Transfer of the chemokine receptor CCR5 between cells by membrane-derived microparticles: A mechanism for cellular human immunodeficiency virus 1 infection[J]. Nature Medicine, 2000, 6(7): 769-775. DOI:10.1038/77498 |

| [19] |

Rozmyslowicz T, Majka M, Kijowski J, et al. Platelet-and megakaryocyte-derived microparticles transfer CXCR4 receptor to CXCR4-null cells and make them susceptible to infection by X4-HIV[J]. AIDS (London, England), 2003, 17(1): 33-42. DOI:10.1097/00002030-200301030-00006 |

| [20] |

Columba Cabezas S, Federico M. Sequences within RNA coding for HIV-1 Gag p17 are efficiently targeted to exosomes[J]. Cellular Microbiology, 2013, 15(3): 412-429. DOI:10.1111/cmi.2013.15.issue-3 |

| [21] |

Jaworski E, Narayanan A, van Duyne R, et al. Human T-lymphotropic virus type 1-infected cells secrete exosomes that contain Tax protein[J]. Journal of biology chemistry, 2014, 289(32): 22284-22305. DOI:10.1074/jbc.M114.549659 |

| [22] |

Cosset FL, Dreux M. HCV transmission by hepatic exosomes establishes a productive infection[J]. Journal of Hepatology, 2014, 60(3): 674-675. DOI:10.1016/j.jhep.2013.10.015 |

| [23] |

Longatti A, Boyd B, Chisari FV. Virion-independent transfer of replication-competent hepatitis C virus RNA between permissive cells[J]. Journal of Virology, 2015, 89(5): 2956-2961. DOI:10.1128/JVI.02721-14 |

| [24] |

Ramakrishnaiah V, Thumann C, Fofana I, et al. Exosome-mediated transmission of hepatitis C virus between human hepatoma Huh7.5 cells[J]. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 2013, 110(32): 13109-13113. DOI:10.1073/pnas.1221899110 |

| [25] |

Lai CK, Saxena V, Tseng CH, et al. Nonstructural protein 5A is incorporated into hepatitis C virus low-density particle through interaction with core protein and microtubules during intracellular transport[J]. PLoS One, 2014, 6: e99022. |

| [26] |

Chivero ET, Stapleton JT. Tropism of human pegivirus (formerly known as GB virus C/hepatitis G virus) and host immunomodulation: insights into a highly successful viral infection[J]. The Journal of General Virology, 2015, 96(7): 1521-1532. DOI:10.1099/vir.0.000086 |

| [27] |

Pleet ML, Mathiesen A, DeMarino C, et al. Ebola VP40 in exosomes can cause immune cell dysfunction[J]. Frontiers in microbiology, 2016, 7(139): 1765-1772. |

| [28] |

Mao LX, Wu J, Shen L, et al. Enterovirus 71 transmission by exosomes establishes a productive infection in human neuroblastoma cells[J]. Virus Genes, 2016, 52(2): 189-194. DOI:10.1007/s11262-016-1292-3 |

| [29] |

Ahsan NA, Sampey GC, Lepene B, et al. Presence of viral RNA and proteins in exosomes from cellular clones resistant to RIFT valley fever virus infection[J]. Frontiers in Microbiology, 2016, 7: 139-155. |

| [30] |

de Carvalho JV, de Castro RO, da Silva EZ, et al. Nef neutralizes the ability of exosomes from CD4+ T cells to act as decoys during HIV-1 infection[J]. PLoS One, 2014, 9(11): e113691. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0113691 |

| [31] |

Aqil M, Naqvi AR, Bano AS, et al. The HIV-1 Nef protein binds argonaute-2 and functions as a viral suppressor of RNA interference[J]. PLoS one, 2013, 8(9): e74472. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0074472 |

| [32] |

Luo XY, Fan Y, Park IW, et al. Exosomes are unlikely involved in intercellular Nef transfer[J]. PLoS One, 2015, 10(4): e0124436. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0124436 |

| [33] |

El-Saghir J, Nassar F, Tawil N, et al. ATL-derived exosomes modulate mesenchymal stem cells: potential role in leukemia progression[J]. Retrovirology, 2016, 13(1): 73-85. DOI:10.1186/s12977-016-0307-4 |

| [34] |

Dreux M, Garaigorta U, Boyd B, et al. Short-range exosomal transfer of viral RNA from infected cells to plasmacytoid dendritic cells triggers innate immunity[J]. Cell Host & Microbe, 2012, 12(4): 558-570. |

| [35] |

Bukong TN, Momen-Heravi F, Kodys K, et al. Exosomes from hepatitis C infected patients transmit HCV infection and contain replication competent viral RNA in complex with Ago2-miR122-HSP90[J]. PLoS Pathogens, 2014, 10(10): e1004424. DOI:10.1371/journal.ppat.1004424 |

| [36] |

Wilson JA, Zhang C, Huys A, et al. Human Ago2 is required for efficient microRNA 122 regulation of hepatitis C virus RNA accumulation and translation[J]. Journal of Virology, 2011, 85(5): 2342-2350. DOI:10.1128/JVI.02046-10 |

| [37] |

Gray LR, Gabuzda D, Cowley D, et al. CD4 and MHC class 1 down-modulation activities of nef alleles from brain and lymphoid tissue-derived primary HIV-1 isolates[J]. Journal of Neuro Virology, 2011, 17(1): 82-91. |

| [38] |

Feng Z, Hensley L, Mcknight KL, et al. A pathogenic picornavirus acquires an envelope by hijacking cellular membranes[J]. Nature, 2013, 496(7445): 367-371. DOI:10.1038/nature12029 |

| [39] |

Longatti A. The dual role of exosomes in hepatitis A and C virus transmission and viral immune activation[J]. Viruses, 2015, 7(12): 6707-6715. DOI:10.3390/v7122967 |

| [40] |

Liu Z, Zhang X, Yu Q, et al. Exosome-associated hepatitis C virus in cell cultures and patient plasma[J]. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications, 2014, 455(3/4): 218-222. |

| [41] |

Laganà A, Russo F, Venezino D, et al. Extracellular circulating viral microRNAs: current knowledge and perspectives[J]. Frontiers of Genetics, 2013, 4: 120-127. |

| [42] |

Esser MT, Graham DR, Coren LV, et al. Differential incorporation of CD45, CD80(B7-1), CD86(B7-2), and major histocompatibility complex class Ⅰ and Ⅱ molecules into human immunodeficiency virus type 1 virions and microvesicles: Implications for viral pathogenesis and immune regulation[J]. Journal of Virology, 2001, 75(13): 6173-6182. DOI:10.1128/JVI.75.13.6173-6182.2001 |

| [43] |

Sun YJ, Yu SQ, Ding N, et al. Autophagy benefits the replication of Newcastle disease virus in chicken cells and tissues[J]. Journal of Virology, 2014, 88(1): 525-537. DOI:10.1128/JVI.01849-13 |

| [44] |

Meng SS, Xu JD, Wu YT, et al. Targeting autophagy to enhance oncolytic virus-based cancer therapy[J]. Expert Opinion on Biological Therapy, 2013, 13(6): 863-873. DOI:10.1517/14712598.2013.774365 |

| [45] |

Meng CC, Zhou ZZ, Jiang K, et al. Newcastle disease virus triggers autophagy in U251 glioma cells to enhance virus replication[J]. Archives of Virology, 2012, 157(6): 1011-1018. DOI:10.1007/s00705-012-1270-6 |

2017, Vol. 44

2017, Vol. 44