扩展功能

文章信息

- 祝丽彬, 汪涯, 颜日明, 张志斌, 朱笃

- ZHU Li-Bin, WANG Ya, YAN Ri-Ming, ZHANG Zhi-Bin, ZHU Du

- 二型态真菌形态调控研究现状与展望

- Advances in dimorphism transition in fungi

- 微生物学通报, 2017, 44(11): 2722-2733

- Microbiology China, 2017, 44(11): 2722-2733

- DOI: 10.13344/j.microbiol.china.170130

-

文章历史

- 收稿日期: 2017-02-20

- 接受日期: 2017-05-15

- 优先数字出版日期(www.cnki.net): 2017-08-31

2. 上海交通大学生命科学技术学院 上海 200240;

3. 江西科技师范大学生命科学学院 江西省生物加工过程重点实验室 江西 南昌 330013

2. School of Life Sciences and Biotechnology, Shanghai Jiao Tong University, Shanghai 200240, China;

3. Key Laboratory of Bioprocess Engineering of Jiangxi Province, College of Life Sciences, Jiangxi Science and Technology Normal University, Nanchang, Jiangxi 330013, China

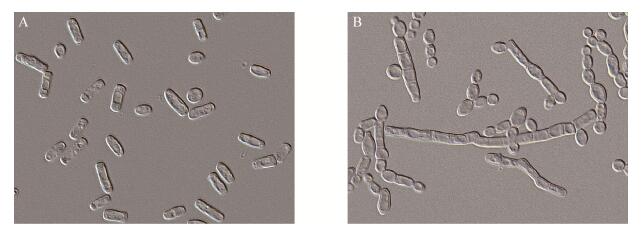

真菌二型态(Dimorphism)又称二型性、二相性或二型现象,是指一些真菌在某些环境因子的影响下,使菌体形态在酵母型与菌丝型两种形态之间发生相互转变的能力[1-2](图 1)。具有二型态能力的真菌很多,在子囊菌、担子菌和接合菌中均存在,其中尤以子囊菌居多。目前研究报道较多的典型二型态真菌主要有:玉米黑粉菌(Ustilago maydis)、白假丝酵母(Candida albicans)、酿酒酵母(Saccharomyces cerevisiae)、解脂酵母(Yarrowia lipolytica)和银耳(Tremella fuciformis)等(表 1)。研究表明,大多数二型态真菌的形态转换与其营养摄取和致病性密切相关[3]。例如酿酒酵母在碳源缺乏的固态琼脂培养基上以侵入性强的酵母型出现,并能在半固体培养基上形成生物膜;而在氮饥饿时,则能转换为假菌丝型[13]。刘娟等[23]发现在不同碳氮比条件下二型态银耳节孢子会在酵母型细胞和菌丝型之间进行转换。相对非致病真菌而言,二型态致病真菌的形态转换与入侵及粘附细胞、分泌胞外蛋白酶等致病过程有关。例如白假丝酵母菌的菌丝型细胞对入侵寄主是必需的,不能形成菌丝的突变体,其致病能力降低或消失[25];申克氏孢子丝菌(Sporothrix schenckii)的酵母型能引起皮肤、皮下组织、勃膜和局部淋巴系统甚至全身多系统的损害,而菌丝型则无致病性[10]。因此,研究致病二型态真菌的生理特性和诱发致病的环境因素,将有助于控制致病二型态真菌的形态,最终控制其致病性。

|

| 图 1 二型态真菌皮状丝孢酵母的两种形态(1 000×) Figure 1 Two morphologies of dimorphic fungi Trichosporon cutaneum (1 000×) 注:A:酵母型;B:菌丝型. Note: A: Yeast form; B: Mycelium form. |

|

|

| 真菌门 Eumycota |

种名 Species |

致病形态 Pathogenic form |

参考文献 References |

| 子囊菌门 Ascomycota |

白假丝酵母 Candida albicans | 菌丝型 Filament | [3] |

| 杜氏假丝酵母 Candida dubliniensis | 菌丝型 Filament | [4] | |

| 热带假丝酵母 Candida tropicalis | 菌丝型 Filament | [5] | |

| 近平滑假丝酵母 Candida parapsilosis | 菌丝型 Filament | [6] | |

| 葡萄牙假丝酵母 Candida lusitaniae | 菌丝型 Filament | [7] | |

| 巴西副球孢子菌 Paracoccidioides brasiliensis | 酵母型 Yeast | [8] | |

| 荚膜组织胞浆菌 Histoplasma capsulatum | 酵母型 Yeast | [9] | |

| 粗球孢子菌 Coccidioides immitis | 酵母型 Yeast | [9] | |

| 申克孢子丝菌 Sporothrix schenckii | 酵母型 Yeast | [10] | |

| 皮炎芽生菌 Blastomyces dermatitidis | 酵母型 Yeast | [9] | |

| 发酵毕赤酵母 Pichia fermentans | - | [1] | |

| 日本裂殖酵母 Schizosaccharomyces japonicus | - | [11] | |

| 酿酒酵母 Saccharomyces cerevisiae | - | [12] | |

| 非洲栗酒酵母 Saccharomyces pombe | - | [13] | |

| 解脂假丝酵母 Yarrowia lipolitica | - | [14] | |

| 马內菲青霉菌 Penicillum marneffei | 酵母型 Yeast | [9] | |

| 榆树枯萎病菌 Ceratocystis ulmi, Ophiostoma novo-ulmi, Ophiostoma ulmi, Ophiostoma himal-ulmi | 菌丝型 Filament | [15] | |

| 长喙壳状表皮藓菌 Ophiostoma floccosum | 菌丝型 Filament | [16] | |

| 玫烟色拟青霉菌 Isaria fumosorosea | 菌丝型 Filament | [17] | |

| 烟曲霉 Aspergillus fumigatus | 菌丝型 Filament | [18] | |

| 出芽短梗霉菌 Aureobasidium pullulans | - | [19] | |

| 串珠镰刀菌 Fusarium moniliforme | 菌丝型 Filament | [20] | |

| 稻瘟病菌 Magnaporthe grisea | 菌丝型 Filament | [18] | |

| 担子菌门 Basidiomycota |

新型隐球菌 Cryptococcus neoformans | 酵母型 Yeast | [9] |

| 格特隐球菌 Cryptococcus gattii | 酵母型 Yeast | [9] | |

| 玉米黑粉菌 Ustilago maydis | 菌丝型 Filament | [21] | |

| 茭白黑粉菌 Ustilago esculenta | 菌丝型 Filament | [22] | |

| 银耳 Tremella fusiformis | - | [23] | |

| 糖秕马拉色菌 Malasesiza furfur | 酵母型 Yeast | [24] | |

| 接合菌门 Zygomycota |

卷枝毛霉 Mucor circinelloides | 菌丝型 Filament | [9] |

| 注:-:未提及. Note: -: Non-described. |

|||

此外,菌体形态调控作为微生物发酵调控的重要内容,对于提高真菌在工业发酵中的生产水平具有重要作用,受到高度重视。以菌丝型生长的真菌会形成分散菌丝体(Dispersed mycelium)、球状菌丝体(Pellet)和团簇状菌丝体(Clump or Flock)等3种集结形态,不论哪种形态,都会对发酵液的流体学性质、营养物质摄取和氧气传递带来影响[26-28]。随着细胞菌丝的增多,真菌细胞间更容易发生结团现象,从而使发酵液的粘度不断增加,进一步阻碍细胞对营养物质的摄取和氧气的传递,最终影响菌体的生长和产物的生成[29]。为此,研究人员根据真菌生长的特性,通过优化培养基的成分及组成来控制丝状真菌形态。如Christiansen等[30]研究了不同葡萄糖浓度下黑曲霉(Aspergillus niger)菌丝体的生长情况,发现在不同糖浓度下,菌丝体的分枝情况会有所区别。桑美纳等[31]采用硫铵-豆油偶联型流加策略,使顶头孢霉(Cephalosporins acremonium)细胞在发酵中期正常分化为高度膨胀菌丝体,减少菌丝结球率,实现了头孢菌素C的高产。Liu等[32]全面考察了接种孢子、葡萄糖、尿素、磷酸盐、金属离子的浓度和发酵体系pH及添加微粒子对米根霉(Rhizopus oryzae)生长形态的影响及其变化规律。

就二型态真菌而言,虽然人们对其形态转换已有较多研究,但大都集中在探索致病真菌的感染机理方面,而探讨如何将二型态真菌的形态调控应用于工业化发酵生产上的研究相当缺乏。因此探索二型态真菌细胞形态调控的环境因子,实现其在发酵过程中形态的有利转换,不但可以促进菌体的生长和产物的合成,实现发酵后期产物的高效分离,而且对于提高其发酵效率和生产水平都具有重要意义。本文就近年来影响真菌二型态的外界环境因子、转化机制和真菌发酵形态控制等方面的研究进展进行综述,以期为阐明二型态真菌的转化机理,丰富和提升真菌形态调控的内容和认识水平提供参考。

1 调控二型态真菌形态转换的环境因子环境因子是二型态真菌形态转换过程中的最初启动因子。对于不同的二型态真菌,影响其形态转换的环境因子也不尽相同,因此探索环境触发因子是研究二型态真菌形态转换的首要任务。目前,关于触发二型态真菌形态转换的环境因子主要有以下几类。

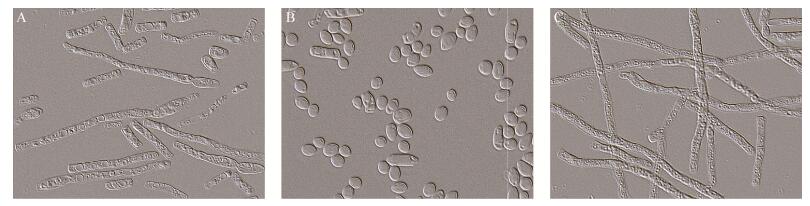

1.1 营养因子营养因子主要是指菌体生长过程中所必需的一些营养成分,如氮源、氨基酸、碳源等,其中氮源是最重要的因子之一。白假丝酵母菌在氮限制情况下,铵离子透性酶Mep2能诱导其细胞由酵母型向菌丝型转变[33]。Lee等发现新型隐球菌在正常培养条件下细胞呈酵母型,而当氮源限制时则以假丝状生长[34]。此外,酿酒酵母菌在氮饥饿时细胞也能够从酵母型转变为假菌丝型[35];而解脂假丝酵母菌在氮源限制条件下,其细胞呈酵母状生长,菌丝型受抑制[16]。发酵毕赤酵母(Pichia fermentans)的细胞形态对氮源浓度高度依赖,在培养基中尿素和磷酸氢二铵的浓度为毫摩尔级时主要以酵母型生长为主,而在微摩尔级则呈假丝状[1]。本课题组也发现,氮源浓度对于皮状丝孢酵母(Trichosporon cutaneum)的形态转换至关重要,正常情况下,皮状丝孢酵母在发酵过程中是以丝状生长为主(图 2A),而在氮源限制的情况下,其形态能发生变化,由菌丝型为主变为酵母型为主(图 2B),增加氮源的供应,细胞又会转为菌丝型生长为主(图 2C)[36]。

|

| 图 2 发酵过程中皮状丝孢酵母的两种形态(1 000×) Figure 2 Two morphologies of Trichosporon cutaneum B3 (1 000×) 注:A:正常发酵条件;B:氮源限制;C:氮源充足. Note: A: Normol condition; B: Nitrogen limitation; C: Nitrogen abundance. |

|

|

此外,研究人员还发现氮源种类,尤其是氨基酸对二型态真菌的菌丝形态变化也有重要影响。如发酵毕赤酵母在含可同化氮源(如酵母提取物、蛋白胨、尿素、磷酸氢二铵等)的培养基中主要呈酵母型;而在含硫酸铵、甲硫氨酸、缬氨酸和苯丙氨酸等作为氮源的培养基中则转化形成假丝[1]。Nickerson最早发现白假丝酵母菌在淀粉培养基上可以产生菌丝和厚膜孢子[37],在添加了半胱氨酸后就只产生酵母细胞,而在含有8种氨基酸(丙氨酸、亮氨酸、赖氨酸、甲硫氨酸、脯氨酸、苯丙氨酸、鸟氨酸、苏氨酸)的Lee培养基中可以形成菌丝[38]。de Lima等也研究发现氨基酸可使近平滑假丝酵母(Candida parapsilosis)的菌落形态和菌丝形态都发生明显变化,特别是瓜氨酸能促使其细胞形成假丝状[10]。

碳源种类也会影响真菌二型态的转换,如乳糖、麦芽糖、半乳糖和N-乙酰葡萄糖胺等能促进白假丝酵母菌的菌丝型发育,但乙醇、甘油和α-脱氧葡萄糖等会抑制其菌丝型的发育[39-40]。此外,研究者也发现在卷枝毛霉(Mucor circinelloides)的形态发育中,酵母型的形成需要己糖存在[41]。解脂假丝酵母菌在含蓖麻油或橄榄油等疏水性碳源的培养基中,菌体呈单细胞酵母型生长,而在以葡萄糖或N-乙酰葡萄糖胺等作为亲水性碳源进行培养时,菌体则转换为菌丝型[42]。葡萄糖浓度同样对真菌形态转换有显著影响,如酿酒酵母在葡萄糖限制条件下呈菌丝型生长[43-44];Buu等研究发现,低葡萄糖浓度(约0.1%)能刺激白假丝酵母菌菌丝体的形成[45]。

1.2 化学因子有些二型态真菌在其形态转换时需添加一些化学物质进行诱导。如脂类物质能促进玉米黑粉菌菌丝型生长,而高级饱和脂肪酸、高级不饱和脂肪酸、厚朴酚以及肉桂醛等对白假丝酵母菌菌丝型的发育有抑制作用[46-48],氧化脂类、水杨酸等会诱导荷兰榆树病原真菌(Ophiostoma ulmi)呈菌丝型生长[49]。尽管荚膜组织胞浆菌(Histoplasmac apsulatum)的二型态受温度控制,但控制其酵母型生长的基因仅能在高温且同时存在巯基的培养条件下才能表达[50]。血清能很好地诱导解脂酵母、日本裂殖酵母(Schizosaccharomyces japonicus)等菌丝的形成[51]。

1.3 物理因子物理因子主要包括温度、pH以及气体环境等。迄今为止,已经发现很多二型态真菌的形态转换与温度密切相关。例如巴西副球孢子菌(Paracoccidioides brasiliensis)是一种典型的依赖于温度的二型态真菌,在20 ℃时呈菌丝型,37 ℃时呈酵母型[12],马尔尼菲青霉菌(Penicillium marneffei)也是一个对温度高度依赖的二型态真菌[52]。Schwartz等[13]曾报道粗球孢子菌(Coccidioides immitis)、荚膜组织胞浆菌(Histoplasma capsulatum)、申克孢子丝菌和皮炎芽生菌(Blastomyces dermatitidis)均在20-25 ℃时呈菌丝型,而当温度升高至37℃时则转化为具有致病性的酵母型;但白假丝酵母则相反,其在25 ℃为酵母型,在37 ℃为菌丝型。在正常条件下(pH 7.0),玉米黑粉菌以酵母型存在,而在酸性条件下(pH 3.0)则以菌丝型生长[19]。在低溶氧条件下(DO < 3%),玫烟色拟青霉菌(Isaria fumosorosea)以菌丝型生长为主,而高溶氧条件下(DO > 20%)则有利于酵母型细胞积累[22];而卷枝毛霉(Mucor circinelloides)则相反,其在有氧条件下呈菌丝型生长,在厌氧条件或高CO2浓度则转化为酵母型生长[53]。对于解脂假丝酵母,半厌氧状态更有利于其呈菌丝型生长[54]。高CO2浓度能有效促进格特隐球菌(Cryptococcus gattii)形成大量单核菌丝体及孢子[55]。在低于37℃情况下,高CO2浓度也可以促进白假丝酵母菌形成菌丝型生长[56]。

1.4 其他环境因子除了上述三类环境因子外,还存在一些其他环境因子也可诱导真菌二型态。榆枯萎病菌(Ceratocystis ulmi)在葡萄糖-脯氨酸-盐的培养基中,当接种量大于106 CFU/mL时,其细胞发育成酵母型;相反,当接种量小于106 CFU/mL时,细胞则成菌丝型,而其他环境因子对其没有影响[17]。长喙壳状表皮藓菌(Ophiostoma floccosum)也存在相同的现象,在以L-脯氨酸作为氮源的培养基中,当接种量为107 CFU/mL时能极大地促进其呈酵母型生长,而当接种量为5×105 CFU/mL时则促使其菌丝型生长[18]。接种量对真菌形态的这种影响可通过群体效应(Quorum sensing)进行解释,即在某些特定条件下,菌体自身会分泌一些群体感应分子,这些群体感应分子的浓度会随着菌体密度的增加而升高,当超过一定的阈值后就会调节菌体的一些生理生化特性发生相应的改变[57]。通常,一些高级醇可作为群体感应分子来调节二型态真菌的形态转换,如法尼醇能抑制白色念珠菌的出芽及生物膜的形成[58],而甲硫醇、正丁醇、异丁醇和异丙醇能诱导发酵毕赤酵母呈假菌丝型生长[1],在酿酒酵母中,异戊基乙醇能通过由Swe1p蛋白激活的Cdc28磷酸化作用而诱导菌丝的形成[59]。2-甲基-1-丁醇、4-羟基苯乙酸和3-甲基戊酸作为荷兰榆树病菌的群体感应分子,能抑制其至少50%的菌体形成芽管[60]。

2 二型态真菌形态转换的机制 2.1 信号转导途径真菌二型态转换的机制是目前研究的热点,迄今已有大量报道,研究内容主要集中在真菌二型态的信号转导途径和基因水平调控等方面[3, 16]。关于二型态真菌的信号转导途径,研究人员已经发现了真菌在形态转换过程中涉及到内部多条信号转导途径,主要包括MAPK途径(Mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway)、cAMP-PKA途径(cAMP-protein kinase A pathway)、TOR (Target of repamycin pathway)途径、Rim101途径和Ca2+/Calcineurin途径等[8, 61-64]。

MAPK途径是调控二型态真菌形态转换过程的重要途径之一(图 3),在酿酒酵母中,Ste11、Ste7和Kss1依次作为MAPKKK (Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase Kinase Kinase)、MAPKK (Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase Kinase)和MAPK (Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase)将接收到的外界信号逐级放大[65]。在葡萄糖限制条件下,AMPK (Adenosine 5′-monophosphate (AMP)-activated protein kinase)途径中的Snf1蛋白激酶可作用于Mig1和Mig2转录抑制因子,然后由Mig1/2联合MAPK途径共同调节其菌丝体形成,同时AMPK途径中的Snf1也可通过Snf1-Nrg途径诱导Flo11基因的表达,促进菌丝形成;而酿酒酵母在氮饥饿等营养条件的刺激下,膜受体蛋白Gpr1和Mep2将信号传递至小G蛋白Ras2和Gpa2,从而激活腺苷酸环化酶生成cAMP,cAMP能激活PKA,从而促进菌丝型的生长[66-68](图 3)。氮饥饿还可诱发酿酒酵母启动TOR途径调节其菌体形态转换,TOR激酶是酿酒酵母感知外界营养条件的一个重要激酶,在氮源缺乏或雷帕霉素处理后,TOR蛋白会从细胞核转向细胞质,然后作用于其下游元件Tap42和Sit4,进而促发氮源阻遏效应引起菌体形态改变,或由磷酸化的Tap42-Sit42复合体促进相关基因的转录与表达,从而使菌体呈菌丝型生长[69](图 3)。

|

| 图 3 酿酒酵母菌丝形成的主要信号通路 Figure 3 Multiple signaling pathways that control filamentous growth in S. cerevisiae 注:Snf1蛋白激酶对于响应葡萄糖限制的许多细胞反应都十分重要. AMPK途径中的Snf1与Nrg1和Nrg2以及Mig1和Mig2都是促进菌丝生长所必需的.小G蛋白Ras2是MAPK通路与cAMP通路中共同的上游蛋白,能够调节菌丝发育. Ras2p或Gpa2p可活化腺苷酸环化酶(Cyr1p),生成的cAMP进而诱导特定基因的表达促使菌丝形成. Tor蛋白激酶在营养传感信号转导通路中发挥作用,当其与雷帕霉素结合后活性受到抑制. TOR信号级联反应途径主要通过氮阻遏(NCR)和Tap42-Sit4磷酸酶复合物调控菌丝的生长. Note: The Snf1, protein kinase that is important for many cellular responses to glucose limitation. The AMPK Snf1, Nrg1, Nrg2, Mig1 and Mig2, were required for filamentous growth in response to glucose limitation. The small G protein Ras2, an important regulator of hyphal development and likely functions upstream of both MAPK pathway and cAMP pathway. Adenylate cyclase (Cyr1p) can be activated by Ras2p or Gpa2p, inducing the expression of specific genes to bring about filamentous growth. Rapamycin binds and inhibits the Tor protein kinases, which function in a nutrient-sensing signal transduction pathway. TOR signaling cascade controls filamentous growth via nitrogen catabolite repression (NCR) and the Tap42-Sit4 phosphatase complex. |

|

|

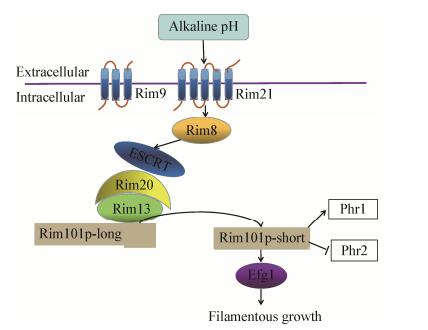

Rim101途径对于白假丝酵母、酿酒酵母、新型隐球菌等二型态真菌响应环境pH而引起的形态分化具有重要作用[70-72]。在碱性条件下,白假丝酵母中受pH调节的phr1基因高效表达,编码形成膜上糖苷酶,膜受体蛋白Rim9及Rim21接收信号并将其传至Rim8与Rim20蛋白,Rim20与Rim101的C端结合,在Rim13的酶切作用下,全长的Rim101水解形成较短的Rim101而具有活性,进而诱导基因efg1表达形成菌丝(图 4)[73]。phr2为细胞膜上糖苷酶的另一个编码基因,其只有在酸性条件下表达,phr2基因缺陷型突变菌株在pH低于5.5时呈菌丝型生长,说明phr2基因能抑制菌丝体形成[74-75]。

|

| 图 4 碱性pH条件下,Rim101途径参与白假丝酵母菌丝形成 Figure 4 Rim101 signaling pathway that controls filamentous growth in C. albicans 注:Rim9和Rim21都是膜受体蛋白.全长Rim101可以被Rim13蛋白酶水解.水解后的短链Rim101p具有活性,对于应答碱性环境的各种反应至关重要,包括碱性诱导基因的活化、碱性抑制基因的抑制以及菌丝的形成. Note: Rim9 and Rim21, plasma membrane receptor proteins. Full-length Rim101 can be processed by Rim13, a calpain-like protease. Processed Rim101p-short is required for the alkaline response, which includes activation of alkaline-induced genes, repression of alkaline-repressed genes, and filamentation. |

|

|

Ca2+/Calcineurin途径则主要参与卷枝毛霉、烟曲霉、稻瘟病菌(Magnaporthe grisea)和念珠菌属中一些二型态真菌的形态转换[8-9]。如热带假丝酵母(Candida tropicalis)在血清等外界环境的作用下,细胞外的Ca2+进入细胞内并与钙调蛋白结合形成Ca2+/CaM复合体。无活性的钙调磷酸酶与Ca2+/CaM复合体结合而具有活性,活化的钙调磷酸酶进一步作用于Crz1转录因子,使其去磷酸化,去磷酸化的Crz1进入细胞核调节相关菌丝形成基因的表达(图 5)[76]。钙调磷酸酶在卷枝毛霉的二型态转换过程中也起至关重要的作用,它能诱导卷枝毛霉由酵母型向菌丝型转变并抑制其细胞内PKA激酶的活性。卷枝毛霉中的钙调磷酸酶含3个催化亚基A (CnaA、CnaB、CnaC)以及1个调节亚基B (CnbR),CnbR对维持钙调磷酸酶的活性十分重要。敲除编码CnbR基因的突变株或用钙调磷酸酶抑制剂FKBP12-FK506或CypA-CsA处理后的菌株,PKA的活性明显升高,菌体呈酵母型生长[77-78]。

|

| 图 5 Ca2+/Calcineurin途径参与的热带假丝酵母菌丝形成 Figure 5 Ca2+/Calcineurin signaling pathway that controls filamentous growth in Candida tropicalis 注:钙调神经磷酸酶(CN)由催化亚基A (Cna)和调节亚基B (Cnb)组成,能被Ca2+/钙调蛋白复合物激活.活化的钙调神经磷酸酶(CN)会促使转录因子CRZ1去磷酸化,进而调节菌丝生长. Note: Calcineurin (CN), consisting of the catalytic A (Cna) and regulatory B (Cnb) subunits, is activated by Ca2+/Calcineurin complex. The transcription factor Crz1, dephosphorylated by activated CN then to regulate filamentous growth. |

|

|

由于二型态真菌的信号转导途径中蛋白酶起到关键的作用,信号分子和调节蛋白从本质上都是受到基因表达的调控,因此研究人员更乐于在基因水平上对触发和调控二型态真菌发生形态转换的分子机制进行研究,并希望寻找到与二型态转化有关的基因。利用基因表达差异分析方法,可以了解二型态真菌细胞在不同生理条件下或在不同生长发育阶段的基因表达差异,从而为阐明二型态真菌的形态转换分子机制提供重要信息。目前研究基因差异表达的主要技术有mRNA差异显示(mRNA differential display,DD)[79]、转录组测序技术(RNA sequencing,RNAseq)[80]、基因表达系列分析(serial analysis of gene expression,SAGE)[81]、代表性差异分析(representational difference analysis,RDA)[82]、抑制消减杂交法(suppression subtractive hybridization,SSH)[83]、交互扣除RNA差别显示技术(reciprocal subtraction differential RNA display,RSDD)[84]和DNA微列阵分析(DNA microarray analysis)[16]等。如Nigg等利用RNAseq技术分别对酵母型和菌丝型的荷兰榆树病菌进行测序,发现两种形态下的菌体有将近12%的基因表达存在差异[85];Marques等[86]利用SSH技术发现ags1和tsa1基因在巴西副球孢子菌的酵母型中有很高的表达;在玉米黑粉菌的cAMP信号转导途径中,利用SSH技术发现编码醛酮还原酶的uor1基因起到重要作用[87],而包含3个RNA识别元件和甘氨酸富集区的蛋白编码基因UmRrm75决定了其菌丝发育[88];Liu等[89]利用SSH技术也发现6个可能与马尔尼菲青霉菌的形态转换有关的基因;Chacko等[90]利用正向遗传筛选法(forward genetic screen)发现RZE1对隐球酵母的形态转换十分重要,RZE1为长链非编码RNA,它能调节znf2的转录与输出,而znf2是控制其形态变化的关键。

3 应用与展望现有研究结果表明,影响真菌二型态转换的环境因素各式各样,不同的环境因子对同一二型态真菌形态转换的作用存在差异,而且相同的环境因子对不同真菌的作用效果也不尽相同,甚至截然相反。各二型态真菌对外界环境刺激的应答的实质是细胞内各种酶、信号分子以及基因相互作用的结果。迄今为止,在影响真菌二型态转化的环境因子和分子机制等方面已开展了一些卓有成效的工作,为其今后在生产、生活中的应用奠定基础。

3.1 抗真菌药物研发二型态真菌的形态与其致病性密切相关,因此研究者希望通过控制真菌形态来改变其毒性。Guirao-Abad等[91]研究发现抗真菌药物两性霉素B能通过抑制白假丝酵母芽管生长而发挥其抗真菌作用,抗真菌药物可能作用于真菌形态转换途径中的某些酶或者基因。这为今后研究提供了新的思路,例如:怎样根据二型态真菌的形态转换与其致病性的关系来开发新的抗真菌药物,二型态真菌形态转换信号途径中的信号受体能否作为药物作用的靶位点从而达到抗真菌的目的,不同细胞形态基因表达的差异是否同致病性有关等。

3.2 真菌发酵形态控制除了研究菌体形态与致病性的联系外,探究菌体发酵形态与其代谢产物之间的关系也备受关注。Braga等运用定量图像分析技术实时监测解脂假丝酵母菌在不同培养条件下的菌体形态以及不同形态菌体代谢产物如γ-癸内酯、胞内脂质等之间的差异[42]。Driouch等[92]与Wucherpfennig等[93]还分别于2010和2011年提出了形态代谢工程学(Metabolic engineering of morphology)的概念,即利用分子生物学原理与图像分析技术分析形态与物质、能量代谢之间的关系,通过分子生物学技术合理改造菌体形态,进而完成对形态与物质、能量代谢最优调控的应用性技术[92-94]。迄今为止,在青霉、曲霉等发酵过程中,将形态学结构信息与宏观生物量、底物消耗、产物合成速率相关联的形态结构动力学已是一种重要研究手段[26-31]。因此,开展二型态真菌发酵形态调控,实现其在发酵过程中形态的有利转换,不但可以提高发酵产量,实现发酵后期产物的高效分离,还可丰富和提升真菌形态调控的内容和认识水平,这都将为现代发酵工业提供参考。

| [1] |

Sanna ML, Zara S, Zara G, et al. Pichia fermentans dimorphic changes depend on the nitrogen source[J]. Fungal Biology, 2012, 116(7): 769-777. DOI:10.1016/j.funbio.2012.04.008 |

| [2] |

Yarrow D. Methods for the isolation, maintenance and identification of yeasts[A]//Kurtzman CP, Fell JW. The Yeasts, A Taxonomic Study[M]. 4th Edition. Amsterdam: Elsevier, 1998: 77-100

|

| [3] |

Boyce KJ, Andrianopoulos A. Fungal dimorphism: the switch from hyphae to yeast is a specialized morphogenetic adaptation allowing colonization of a host[J]. FEMS Microbiology Reviews, 2015, 39(6): 797-811. DOI:10.1093/femsre/fuv035 |

| [4] |

Chen YL, Brand A, Morrison EL, et al. Calcineurin controls drug tolerance, hyphal growth, and virulence in Candida dubliniensis[J]. Eukaryotic Cell, 2011, 10(6): 803-819. DOI:10.1128/EC.00310-10 |

| [5] |

Chen YL, Yu SJ, Huang HY, et al. Calcineurin controls hyphal growth, virulence, and drug tolerance of Candida tropicalis[J]. Eukaryotic Cell, 2014, 13(7): 844-854. DOI:10.1128/EC.00302-13 |

| [6] |

Kim SK, El Bissati KE, Mamoun CB. Amino acids mediate colony and cell differentiation in the fungal pathogen Candida parapsilosis[J]. Microbiology, 2006, 152(10): 2885-2894. DOI:10.1099/mic.0.29180-0 |

| [7] |

Young LY, Lorenz MC, Heitman J. A STE12 homolog is required for mating but dispensable for filamentation in Candida lusitaniae[J]. Genetics, 2000, 155(1): 17-29. |

| [8] |

Chaves AF, Navarro MV, Castilho DG, et al. A conserved dimorphism-regulating histidine kinase controls the dimorphic switching in Paracoccidioides brasiliensis[J]. FEMS Yeast Research, 2016, 16(5): fow047. DOI:10.1093/femsyr/fow047 |

| [9] |

Wang LQ, Lin XR. Morphogenesis in fungal pathogenicity: Shape, Size, and Surface[J]. PLoS Pathogens, 2012, 8(12): e1003027. DOI:10.1371/journal.ppat.1003027 |

| [10] |

de Lima Barros MB, de Almeida Paes R, Schubach AO. Sporothrix schenckii and Sporotrichosis[J]. Clinical Microbiology Reviews, 2011, 24(4): 633-654. DOI:10.1128/CMR.00007-11 |

| [11] |

Papp L, Sipiczki M, Holb IJ, et al. Optimal conditions for mycelial growth of Schizosaccharomyces japonicus cells in liquid medium: it enables the molecular investigation of dimorphism[J]. Yeast, 2014, 31(12): 475-482. |

| [12] |

Bastidas RJ, Heitman J. Trimorphic stepping stones pave the way to fungal virulence[J]. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 2009, 106(2): 351-352. DOI:10.1073/pnas.0811994106 |

| [13] |

Schwartz MA, Madhani HD. Principles of MAP kinase signaling specificity in Saccharomyces cerevisiae[J]. Annual Review of Genetics, 2004, 38(1): 725-748. DOI:10.1146/annurev.genet.39.073003.112634 |

| [14] |

Morales-Vargas AT, Domínguez A, Ruiz-Herrera J. Identification of dimorphism-involved genes of Yarrowia lipolytica by means of microarray analysis[J]. Research in Microbiology, 2012, 163(5): 378-387. DOI:10.1016/j.resmic.2012.03.002 |

| [15] |

Wedge M, Naruzawa ES, Nigg M, et al. Diversity in yeast-mycelium dimorphism response of the Dutch elm disease pathogens: the inoculum size effect[J]. Canadian Journal of Microbiology, 2016, 62(6): 525-529. DOI:10.1139/cjm-2015-0795 |

| [16] |

Berrocal A, Oviedo C, Nickerson KW, et al. Quorum sensing activity and control of yeast-mycelium dimorphism in Ophiostoma floccosum[J]. Biotechnology Letters, 2014, 36(7): 1503-1513. DOI:10.1007/s10529-014-1514-5 |

| [17] |

Jackson MA. Dissolved oxygen levels affect dimorphic growth by the entomopathogenic fungus Isaria fumosorosea[J]. Biocontrol Science and Technology, 2012, 22(1): 67-79. DOI:10.1080/09583157.2011.642339 |

| [18] |

Chen YL, Kozubowski L, Cardenas ME, et al. On the roles of calcineurin in fungal growth and pathogenesis[J]. Current Fungal Infection Reports, 2010, 4(4): 244-255. DOI:10.1007/s12281-010-0027-5 |

| [19] |

Jürgensen CW, Jacobsen NR, Emri T, et al. Glutathione metabolism and dimorphism in Aureobasidium pullulans[J]. Journal of Basic Microbiology, 2001, 41(2): 131-137. DOI:10.1002/(ISSN)1521-4028 |

| [20] |

Wang ZG, Liu XM, Cong LM, et al. Characteristics of producing-fumonisin and dimorphic fungus of Fusarium moniliforme[J]. Chinese Journal of Preventive Medicine, 2000, 34(1): 44-46. 王志刚, 刘秀梅, 丛黎明, 等. 串珠镰刀菌产伏马菌素和二相性真菌特性[J]. 中华预防医学杂志, 2000, 34(1): 44-46. |

| [21] |

Cervantes-Montelongo JA, Aréchiga-Carvajal ET, Ruiz-Herrera J. Adaptation of Ustilago maydis to extreme pH values: a transcriptomic analysis[J]. Journal of Basic Microbiology, 2016, 56(11): 1222-1233. DOI:10.1002/jobm.v56.11 |

| [22] |

You WY, Liu Q, Zou KQ, et al. Morphological and molecular differences in two strains of Ustilago esculenta[J]. Current Microbiology, 2011, 62(1): 44-54. DOI:10.1007/s00284-010-9673-7 |

| [23] |

Liu J, Hou LH, Yang SX, et al. Effects of environmental factors on phase transition of arthrospores in Dimorphic Tremella fuciformis[J]. Journal of Wuhan University (Natural Science Edition), 2007, 53(6): 737-740. 刘娟, 侯丽华, 杨双熙, 等. 环境因子对二型态银耳节孢子形态转换的影响[J]. 武汉大学学报:理学版, 2007, 53(6): 737-740. |

| [24] |

Juntachai W, Kajiwara S. Differential expression of extracellular lipase and protease activities of mycelial and yeast forms in Malassezia furfur[J]. Mycopathologia, 2015, 180(3/4): 143-151. |

| [25] |

Xie CF, Sun LM, Meng LH, et al. Sesquiterpenes from Carpesium macrocephalum inhibit Candida albicans biofilm formation and dimorphism[J]. Bioorganic & Medicinal Chemistry Letters, 2015, 25(22): 5409-5411. |

| [26] |

Xiong Q, Xu Q, Gu S, et al. Controlling the morphology of filamentous fungi for optimization of fermentation process[J]. Chinese Journal of Biotechnology, 2012, 28(2): 178-190. 熊强, 徐晴, 顾帅, 等. 丝状真菌形态控制及其在发酵过程优化中的应用[J]. 生物工程学报, 2012, 28(2): 178-190. |

| [27] |

Zheng ZM, Zhao GH, Wang P, et al. Metabolic engineering of Penicillium chrysogenum morphology[J]. Chinese Science Bulletin, 2014, 59(21): 2017-2032. 郑之明, 赵根海, 王鹏, 等. 产黄青霉形态代谢工程研究进展[J]. 科学通报, 2014, 59(21): 2017-2032. |

| [28] |

Wucherpfennig T, Kiep KA, Driouch H, et al. Morphology and rheology in filamentous cultivations[J]. Advances in Applied Microbiology, 2010, 72: 89-136. DOI:10.1016/S0065-2164(10)72004-9 |

| [29] |

Papagianni M. Fungal morphology and metabolite production in submerged mycelial processes[J]. Biotechnology Advances, 2004, 22(3): 189-259. DOI:10.1016/j.biotechadv.2003.09.005 |

| [30] |

Christiansen T, Spohr AB, Nielsen J. On-line study of growth kinetics of single hyphae of Aspergillus oryzae in a flow-through cell[J]. Biotechnology and Bioengineering, 2000, 63(2): 147-153. |

| [31] |

Sang MN, Yuan GQ, Li HF, et al. Cephalosporin C fermentation performance under different ammonium sulfate and soybean oil feeding strategies[J]. Microbiology China, 2011, 38(9): 1321-1330. 桑美纳, 袁国强, 李红飞, 等. 不同补料控制方式发酵生产头孢菌素C的性能比较[J]. 微生物学通报, 2011, 38(9): 1321-1330. |

| [32] |

Liu Y, Liao W, Chen SL. Study of pellet formation of filamentous fungi Rhizopus oryzae using a multiple logistic regression model[J]. Biotechnology and Bioengineering, 2008, 99(1): 117-128. DOI:10.1002/(ISSN)1097-0290 |

| [33] |

Morschh user J. Nitrogen regulation of morphogenesis and protease secretion in Candida albicans[J]. International Journal of Medical Microbiology, 2011, 301(5): 390-394. DOI:10.1016/j.ijmm.2011.04.005 |

| [34] |

Lee S, Phadke S, Sun S, et al. Pseudohyphal growth of Cryptococcus neoformans is a reversible dimorphic transition in response to ammonium that requires the Amt1 and Amt2 ammonium permeases[J]. Eukaryotic Cell, 2012, 11(11): 1391-1398. DOI:10.1128/EC.00242-12 |

| [35] |

Orlova M, Ozcetin H, Barrett L, et al. Roles of the Snf1-activating kinases during nitrogen limitation and pseudohyphal differentiation in Saccharomyces cerevisiae[J]. Eukaryotic Cell, 2010, 9(1): 208-214. DOI:10.1128/EC.00216-09 |

| [36] |

Zhu LB, Wang Y, Zhang ZB, et al. Influence of environmental and nutritional conditions on yeast-mycelial dimorphic transition in Trichosporon cutaneum[J]. Biotechnology & Biotechnological Equipment, 2017, 31(3): 516-526. |

| [37] |

Nickerson WJ, Mankowski Z. Role of nutrition in the maintenance of the yeast-shape in Candida[J]. American Journal of Botany, 1953, 40(8): 584-592. DOI:10.2307/2438443 |

| [38] |

Lee KL, Buckley HR, Campbell CC. An amino acid liquid synthetic medium for the development of mycelial and yeast forms of Candida albicans[J]. Medical Mycology, 1975, 13(2): 148-153. DOI:10.1080/00362177585190271 |

| [39] |

Naseem S, Gunasekera A, Araya E, et al. N-Acetylglucosamine (GlcNAc) induction of hyphal morphogenesis and transcriptional responses in Candida albicans are not dependent on its metabolism[J]. Journal of Biological Chemistry, 2011, 286(33): 28671-28680. DOI:10.1074/jbc.M111.249854 |

| [40] |

Herrero AB, López MC, Fernández-Lago L, et al. Candida albicans and Yarrowia lipolytica as alternative models for analysing budding patterns and germ tube formation in dimorphic fungi[J]. Microbiology, 1999, 145(10): 2727-2737. DOI:10.1099/00221287-145-10-2727 |

| [41] |

Wolff AM, Arnau J. Cloning of glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase-encoding genes in Mucor circinelloides (Syn. racemosus) and use of the gpd1 promoter for recombinant protein production[J]. Fungal Genetics and Biology, 2002, 35(1): 21-29. DOI:10.1006/fgbi.2001.1313 |

| [42] |

Braga A, Mesquita DP, Amaral AL, et al. Quantitative image analysis as a tool for Yarrowia lipolytica dimorphic growth evaluation in different culture media[J]. Journal of Biotechnology, 2016, 217: 22-30. DOI:10.1016/j.jbiotec.2015.10.023 |

| [43] |

Cullen PJ, Sprague GF Jr. Glucose depletion causes haploid invasive growth in yeast[J]. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 2000, 97(25): 13619-13624. DOI:10.1073/pnas.240345197 |

| [44] |

Johnson C, Kweon HK, Sheidy D, et al. The yeast sks1p kinase signaling network regulates pseudohyphal growth and glucose response[J]. PLoS Genetics, 2014, 10(3): e1004183. DOI:10.1371/journal.pgen.1004183 |

| [45] |

Buu LM, Chen YC. Impact of glucose levels on expression of hypha-associated secreted aspartyl proteinases in Candida albicans[J]. Journal of Biomed Science, 2014, 21(1): 22. DOI:10.1186/1423-0127-21-22 |

| [46] |

Klose J, de Sá MM, Kronstad JW. Lipid-induced filamentous growth in Ustilago maydis[J]. Molecular Microbiology, 2004, 52(3): 823-835. DOI:10.1111/j.1365-2958.2004.04019.x |

| [47] |

Sun LM, Liao K, Wang DY. Effects of magnolol and honokiol on adhesion, yeast-hyphal transition, and formation of biofilm by Candida albicans[J]. PLoS One, 2015, 10(2): e0117695. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0117695 |

| [48] |

Taguchi Y, Hasumi Y, Abe S, et al. The effect of cinnamaldehyde on the growth and the morphology of Candida albicans[J]. Medical Molecular Morphology, 2013, 46(1): 8-13. DOI:10.1007/s00795-012-0001-0 |

| [49] |

Naruzawa ES, Bernier L. Control of yeast-mycelium dimorphism in vitro in Dutch elm disease fungi by manipulation of specific external stimuli[J]. Fungal Biology, 2014, 118(11): 872-884. DOI:10.1016/j.funbio.2014.07.006 |

| [50] |

Klein BS, Tebbets B. Dimorphism and virulence in fungi[J]. Current Opinion Microbiology, 2007, 10(4): 314-319. DOI:10.1016/j.mib.2007.04.002 |

| [51] |

Kim J, Cheon SA, Park S, et al. Serum-induced hypha formation in the dimorphic yeast Yarrowia lipolytica[J]. FEMS Microbiology Letter, 2006, 190(1): 9-12. |

| [52] |

Bugeja HE, Hynes MJ, Andrianopoulos A. AreA controls nitrogen source utilisation during both growth programs of the dimorphic fungus Penicillium marneffei[J]. Fungal Biology, 2011, 116(1): 145-154. |

| [53] |

Lübbehüsen TL, Nielsen J, Mclntyre M. Morphology and physiology of the dimorphic fungus Mucor circinelloides (syn. M. racemosus) during anaerobic growth[J]. Mycological Research, 2003, 107(2): 223-230. DOI:10.1017/S0953756203007299 |

| [54] |

Palande AS, Kulkarni SV, León-Ramirez C, et al. Dimorphism and hydrocarbon metabolism in Yarrowia lipolytica var. indica[J]. Archives of Microbiology, 2014, 196(8): 545-556. DOI:10.1007/s00203-014-0990-2 |

| [55] |

Ren P, Chaturvedi V, Chaturvedi S. Carbon dioxide is a powerful inducer of monokaryotic hyphae and spore development in Cryptococcus gattii and carbonic anhydrase activity is dispensable in this dimorphic transition[J]. PLoS One, 2014, 9(12): e113147. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0113147 |

| [56] |

Stichternoth C, Fraund A, Setiadi E, et al. Sch9 kinase integrates hypoxia and CO2 sensing to suppress hyphal morphogenesis in Candida albicans[J]. Eukaryotic Cell, 2011, 10(4): 502-511. DOI:10.1128/EC.00289-10 |

| [57] |

Albuquerque P, Casadevall A. Quorum sensing in fungi-a review[J]. Medical Mycology, 2012, 50(4): 337-345. DOI:10.3109/13693786.2011.652201 |

| [58] |

Hornby JM, Jensen EC, Lisec AD, et al. Quorum sensing in the dimorphic fungus Candida albicans is mediated by farnesol[J]. Applied and Environment Microbiology, 2001, 67(7): 2982-2992. DOI:10.1128/AEM.67.7.2982-2992.2001 |

| [59] |

Martínez-Anaya C, Dickinson JR, Sudbery PE. In yeast, the pseudohyphal phenotype induced by isoamyl alcohol results from the operation of the morphogenesis checkpoint[J]. Journal of Cell Science, 2003, 116(16): 3423-3431. DOI:10.1242/jcs.00634 |

| [60] |

Berrocal A, Navarrete J, Oviedo C, et al. Quorum sensing activity in Ophiostoma ulmi: effects of fuel oils and branched chain amino acids on yeast-mycelial dimorphism[J]. Journal of Applied Microbiology, 2012, 113(1): 126-134. DOI:10.1111/jam.2012.113.issue-1 |

| [61] |

Choi J, Jung WH, Kronstad JW. The cAMP/protein kinase A signaling pathway in pathogenic basidiomycete fungi: Connections with iron homeostasis[J]. Journal of Microbiology, 2015, 53(9): 579-587. DOI:10.1007/s12275-015-5247-5 |

| [62] |

Hnisz D, Majer O, Frohner IE, et al. The Set3/Hos2 histone deacetylase complex attenuates cAMP/PKA signaling to regulate morphogenesis and virulence of Candida albicans[J]. PLoS Pathogens, 2010, 6(5): e1000889. DOI:10.1371/journal.ppat.1000889 |

| [63] |

Rohde JR, Cardenas ME. Nutrient signaling through TOR kinases controls gene expression and cellular differentiation in fungi[A]//Thomas G, Sabatini DM, Hall MN. TOR: Target of Rapamycin[M]. Berlin Heidelberg: Springer, 2004, 279: 53-72

|

| [64] |

O'Meara TR, Norton D, Price MS, et al. Interaction of Cryptococcus neoformans Rim101 and protein kinase A regulates capsule[J]. PLoS Pathogens, 2010, 6(2): e1000776. DOI:10.1371/journal.ppat.1000776 |

| [65] |

Roberts RL, Fink GR. Elements of a single MAP kinase cascade in Saccharomyces cerevisiae mediate two developmental programs in the same cell type: mating and invasive growth[J]. Genes and Development, 1994, 8(24): 2974-2985. DOI:10.1101/gad.8.24.2974 |

| [66] |

Karunanithi S, Cullen PJ. The filamentous growth MAPK pathway responds to glucose starvation through the Mig1/2 transcriptional repressors in Saccharomyces cerevisiae[J]. Genetics, 2012, 192(3): 869-887. DOI:10.1534/genetics.112.142661 |

| [67] |

Kuchin S, Vyas VK, Carlson M. Snf1 protein kinase and the repressors Nrg1 and Nrg2 regulate FLO11, haploid invasive growth, and diploid pseudohyphal differentiation[J]. Molecular and Cellular Biology, 2002, 22(12): 3994-4000. DOI:10.1128/MCB.22.12.3994-4000.2002 |

| [68] |

Pan XW, Heitman J. Cyclic AMP-dependent protein kinase regulates pseudohyphal differentiation in Saccharomyces cerevisiae[J]. Molecular and Cellular Biology, 1999, 19(7): 4874-4887. DOI:10.1128/MCB.19.7.4874 |

| [69] |

Cutler NS, Pan XW, Heitman J, et al. The TOR signal transduction cascade controls cellular differentiation in response to nutrients[J]. Molecular Biology of the Cell, 2001, 12(12): 4103-4113. DOI:10.1091/mbc.12.12.4103 |

| [70] |

Ost KS, O'Meara TR, Huda N, et al. The Cryptococcus neoformans alkaline response pathway: identification of a novel rim pathway activator[J]. PLoS Genetics, 2015, 11(4): e1005159. DOI:10.1371/journal.pgen.1005159 |

| [71] |

Selvig K, Alspaugh JA. pH response pathways in fungi: adapting to host-derived and environmental signals[J]. Mycobiology, 2011, 39(4): 249-256. DOI:10.5941/MYCO.2011.39.4.249 |

| [72] |

Du H, Huang GH. Environmental pH adaption and morphological transitions in Candida albicans[J]. Current Genetics, 2016, 62(2): 283-286. DOI:10.1007/s00294-015-0540-8 |

| [73] |

Davis DA. How human pathogenic fungi sense and adapt to pH: the link to virulence[J]. Current Opinion in Microbiology, 2009, 12(4): 365-370. DOI:10.1016/j.mib.2009.05.006 |

| [74] |

Huang GH. Regulation of phenotypic transitions in the fungal pathogen Candida albicans[J]. Virulence, 2012, 3(3): 251-261. DOI:10.4161/viru.20010 |

| [75] |

Davis D, Wilson RB, Mitchell AP. RIM101-dependent and-independent pathways govern pH responses in Candida albicans[J]. Molecular and Cellular Biology, 2000, 20(3): 971-978. DOI:10.1128/MCB.20.3.971-978.2000 |

| [76] |

Liu SY, Hou YL, Liu WG, et al. Components of the Calcium-Calcineurin signaling pathway in fungal cells and their potential as antifungal targets[J]. Eukaryotic Cell, 2015, 14(4): 324-334. DOI:10.1128/EC.00271-14 |

| [77] |

Lee SC, Li A, Calo S, et al. Calcineurin plays key roles in the dimorphic transition and virulence of the human pathogenic Zygomycete Mucor circinelloides[J]. PLoS Pathogens, 2013, 9(9): e1003625. DOI:10.1371/journal.ppat.1003625 |

| [78] |

Lee SC, Li A, Calo S, et al. Calcineurin orchestrates dimorphic transitions, antifungal drug responses and host-pathogen interactions of the pathogenic mucoralean fungus Mucor circinelloides[J]. Molecular Microbiology, 2015, 97(5): 844-865. DOI:10.1111/mmi.2015.97.issue-5 |

| [79] |

Liu YH, Liu K, Ai YF, et al. Differential display analysis of cDNA fragments potentially involved in Nostoc flagelliforme response to osmotic stress[J]. Journal of Applied Phycology, 2012, 24(6): 1487-1494. DOI:10.1007/s10811-012-9806-4 |

| [80] |

Irmer H, Tarazona S, Sasse C, et al. RNAseq analysis of Aspergillus fumigatus in blood reveals a just wait and see resting stage behavior[J]. BMC Genomics, 2015, 16(1): 1. DOI:10.1186/1471-2164-16-1 |

| [81] |

Irie T, Matsumura H, Terauchi R, et al. Serial analysis of gene expression (SAGE) of Magnaporthe grisea: genes involved in appressorium formation[J]. Molecular Genetics and Genomics, 2003, 270(2): 181-189. DOI:10.1007/s00438-003-0911-6 |

| [82] |

Morgan MB, Parker CC, Robinson JW, et al. Using Representational Difference Analysis to detect changes in transcript expression of Aiptasia genes after laboratory exposure to lindane[J]. Aquatic Toxicology, 2012, 110/111: 66-73. DOI:10.1016/j.aquatox.2012.01.001 |

| [83] |

Murat C, Zampieri E, Vallino M, et al. Genomic suppression subtractive hybridization as a tool to identify differences in mycorrhizal fungal genomes[J]. FEMS Microbiology Letters, 2011, 318(2): 115-122. DOI:10.1111/fml.2011.318.issue-2 |

| [84] |

Kang DC, LaFrance R, Su ZZ, et al. Reciprocal subtraction differential RNA display: an efficient and rapid procedure for isolating differentially expressed gene sequences[J]. Proceeding of the National Academy of Science of the United States of America, 1998, 95(23): 13788-13793. DOI:10.1073/pnas.95.23.13788 |

| [85] |

Nigg M, Laroche J, Landry CR, et al. RNAseq analysis highlights specific transcriptome signatures of yeast and mycelial growth phases in the Dutch Elm disease fungus Ophiostoma novo-ulmi[J]. G3: Genes, Genomes, Genetics, 2015, 5(11): 2487-2495. |

| [86] |

Marques ER, Ferreira MES, Drummond RDD, et al. Identification of genes preferentially expressed in the pathogenic yeast phase of Paracoccidioides brasiliensis, using suppression subtraction hybridization and differential macroarray analysis[J]. Molecular Genetics and Genomics, 2004, 271(6): 667-677. |

| [87] |

Andrews DL, García-Pedrajas MD, Gold SE. Fungal dimorphism regulated gene expression in Ustilago maydis: I. Filament up-regulated genes[J]. Molecular Plant Pathology, 2004, 5(4): 281-293. DOI:10.1111/mpp.2004.5.issue-4 |

| [88] |

Rodríguez-Kessler M, Baeza-Monta ez L, García-Pedrajas MD, et al. Isolation of UmRrm75, a gene involved in dimorphism and virulence of Ustilago maydis[J]. Microbiological Research, 2011, 167(5): 270-282. |

| [89] |

Liu HF, Xi LY, Zhang JM, et al. Identifying differentially expressed genes in the dimorphic fungus Penicillium marneffei by suppression subtractive hybridization[J]. FEMS Microbiology Letters, 2007, 270(1): 97-103. DOI:10.1111/fml.2007.270.issue-1 |

| [90] |

Chacko N, Zhao YB, Yang EC, et al. The lncRNA RZE1 controls Cryptococcal morphological transition[J]. PLoS Genetics, 2015, 11(11): e1005692. DOI:10.1371/journal.pgen.1005692 |

| [91] |

Guirao-Abad JP, González-Párraga P, Argüelles JC. Strong correlation between the antifungal effect of amphotericin B and its inhibitory action on germ-tube formation in a Candida albicans URA+ strain[J]. International Microbiology, 2015, 18(1): 25-31. |

| [92] |

Driouch H, Sommer B, Wittmann C. Morphology engineering of Aspergillus niger for improved enzyme production[J]. Biotechnology and Bioengineering, 2010, 105(6): 1058-1068. |

| [93] |

Wucherpfennig T, Hestler T, Krull R. Morphology engineering-osmolality and its effect on Aspergillus niger morphology and productivity[J]. Microbial Cell Factories, 2011, 10: 58. DOI:10.1186/1475-2859-10-58 |

| [94] |

Zhang AH, Ji XJ, Nie ZK, et al. Progress in influence factors on morphology of Mortierella alpina producing arachidonic acid-rich oil[J]. Chemical Industry and Engineering Progress, 2013, 32(5): 1102-1107. 张瑷珲, 纪晓俊, 聂志奎, 等. 高山被孢霉菌丝形态结构及其对产花生四烯酸油脂影响的研究进展[J]. 化工进展, 2013, 32(5): 1102-1107. |

2017, Vol. 44

2017, Vol. 44