扩展功能

文章信息

- 张晨, 李晓蕾, 李梦, 王秀伶, 郝庆红, 于秀梅

- ZHANG Chen, LI Xiao-Lei, LI Meng, WANG Xiu-Ling, HAO Qing-Hong, YU Xiu-Mei

- 对黄豆苷原具转化作用的耐氧突变株Aeroto-AUH-JLC140未知代谢产物分离、鉴定及抗氧化活性测定

- Isolation, identification and anti-oxidative activity of metabolites from oxygen-tolerant mutant strain Aeroto-AUH-JLC140 capable of biotransforming daidzein

- 微生物学通报, 2016, 43(8): 1699-1707

- Microbiology China, 2016, 43(8): 1699-1707

- DOI: 10.13344/j.microbiol.china.150609

-

文章历史

- 收稿日期: 2015-08-11

- 接受日期: 2016-01-21

- 优先数字出版日期(www.cnki.net): 2016-01-21

大豆异黄酮(soy isoflavones)是大豆在其生长过程中形成的一类次生代谢产物,主要包括黄豆苷原(daidzein)、染料木素(Genistein)和黄豆黄素(Glycitein)。大豆异黄酮具有抗氧化[1]、抗癌[2-3]、预防骨质疏松[4-5]和改变血脂水平[6]等作用。体内外研究均表明,被机体摄入的黄豆苷原可被胃肠道微生物代谢为二氢黄豆苷原(dihydrodaidzein,DHD)、雌马酚(Equol)和去氧甲基安哥拉紫檀素(O-Desmethylangolensin,O-Dma)等多种代谢产物[7-8]。

严格厌氧细菌AUH-JLC140 (Clostridium sp.)是本实验室从公鸡新鲜粪样中分离得到的革兰氏阳性梭菌,该菌株在厌氧条件下能将底物黄豆苷原高效转化为O-Dma[9]。O-Dma不仅与人体雌激素受体ERα和ERβ的亲和力高于其前体黄豆苷原,而且与ERβ结合后,在诱导基因转录方面也强于黄豆苷原[10-11]。此外,当浓度高于10 µmol/L时,O-Dma能够明显抑制人乳腺癌细胞MCF-7的生长[12]。

由于AUH-JLC140为严格厌氧菌株,其转接、培养以及转化过程均必需在严格厌氧条件下进行,而长期维持严格厌氧环境需要大量资金投入。为提高AUH-JLC140的耐氧能力,本实验室对其进行了耐氧驯化,并得到其耐氧突变株Aeroto-AUH-JLC140[13]。与原出发菌株AUH-JLC140相比,耐氧突变株Aeroto-AUH-JLC140培养液中检测到一种未知代谢产物。本研究对该未知代谢产物进行分离纯化和结构鉴定,并测定其抗氧化能力,从微生物代谢产物方面为菌株Aeroto-AUH-JLC140的耐氧机制提供新依据。

1 材料与方法 1.1 材料 1.1.1 细菌菌株: 能将底物黄豆苷原高效转化为O-Dma的严格厌氧细菌菌株AUH-JLC140 (Clostridium sp.)[9]以及菌株AUH-JLC140的耐氧突变菌株Aeroto-AUH-JLC140[13],两菌株均由本实验室保藏。 1.1.2 培养基及菌株培养条件: 严格厌氧梭菌AUH-JLC140的培养条件为:将-80℃冷冻保藏的菌株AUH-JLC140在Concept 400厌氧工作站内迅速解冻,并以10%接种量接种到盛有1 mL新鲜BHI液体培养基的带盖螺口玻璃试管中,试管盖自然拧紧后松半扣,接种后在厌氧工作站内静置培养18−24 h即为种子液。厌氧工作站内混合气体种类及配比为:5% CO2,10% H2和85% N2,厌氧工作站内温度设定为37℃。耐氧突变株Aeroto-AUH-JLC140的培养条件为:将−80℃冷冻保藏的菌株Aeroto-AUH-JLC140在37℃水浴下迅速解冻,在超净工作台内以10%接种量接种到盛有4 mL新鲜BHI液体培养基(培养基高度不低于4 cm)的带盖螺口玻璃试管中,试管盖自然拧紧后松半扣,将接种后的试管放在37℃普通生化培养箱内静置培养8−12 h即为种子液。 1.1.3 主要试剂和仪器: 所用培养基为脑心浸液培养基(Brain heart infusion,BHI),美国Bacto公司;Kovac试剂(有效成分对二甲氨基苯甲醛),南京森贝伽生物科技有限公司;乙腈、乙酸乙酯和甲醇等有机溶剂均为色谱纯,美国Fisher公司。 Concept 400厌氧工作站,英国Ruskinn公司;高效液相色谱仪,美国Waters公司;离心浓缩仪DI-VCOIO-IR,韩国Daiki公司;ESI源Finnigan LCQ Deca离子阱质谱仪,美国Thermo Finnigan公司;Bruker AVANCE 400 MHz超导核磁共振波谱仪,瑞士Bruker公司;DU-650紫外可见分光光度计,美国Beckman公司;pH211型酸度计,意大利HANNA公司;RE-2000型旋转蒸发仪,上海亚荣生化仪器厂。 1.2 耐氧突变株所产未知物质的高效液相检测在超净工作台内将Aeroto-AUH-JLC140的种子液接种在新鲜BHI液体培养基中,具体接种及培养方法同1.1.2。菌株在普通生化培养箱内静置培养12 h后,用等体积乙酸乙酯进行萃取,萃取液在离心浓缩仪内蒸干,将蒸干物重新溶解在100%甲醇溶剂中,过0.45μm有机滤膜,用高效液相色谱进行检测。检测采用C18-ODS分析柱(5 µm,250 mm×4.6 mm),流动相为乙腈和水,其中A液为90%水和10%乙腈以及0.1%冰醋酸,B液为90%乙腈和10%水以及0.1%冰醋酸,A:B为60:40,检测波长为285 nm,流速为1 mL/min。为确定未知物质产生是否与添加底物黄豆苷原有关,按上述接种条件接种后,向带盖螺口玻璃试管中加入终浓度为0.1 mmol/L的底物黄豆苷原,在普通生化培养箱内静置培养12 h后对样品进行萃取,萃取、蒸干以及高效液相检测方法同上。

为检测严格厌氧梭菌AUH-JLC140在生长过程中是否产生未知物质,按1.1.2中所述方法,在厌氧工作站内将菌株AUH-JLC140的种子液接种到新鲜BHI液体培养基中,并添加终浓度0.1 mmol/L的底物黄豆苷原,以不添加黄豆苷原的作为对照,菌株AUH-JLC140的培养、样品萃取及检测方法同上。

1.3 未知物质的分离与制备将20 mL培养好的Aeroto-AUH-JLC140种子液接种到装有200 mL新鲜BHI液体培养基的输液瓶中,输液瓶口用铝箔纸盖好,于普通生化培养箱内37℃培养12 h。培养液用等体积乙酸乙酯萃取后用旋转蒸发仪蒸干,蒸干后样品处理方法同1.2,最后用半制备高效液相色谱对未知物质进行分离。所用色谱柱为Kromasil C18 (5 µm,250 mm×10 mm),将未知物质放置4℃保存待用。

1.4 未知物质的化学结构鉴定 1.4.1 吲哚显色反应: 取2 mL耐氧突变株Aeroto-AUH-JLC140的培养液于带盖螺口玻璃试管中,向试管中加入1 mL乙醚进行萃取,静置分层后沿着试管壁缓缓加入150 µL Kovac试剂,观察颜色变化,具体方法参照文献[14]。 1.4.2 质谱检测: 将纯化后的未知物质注入ESI源质谱仪进行测定。 1.4.3 核磁共振检测: 将纯化后的未知物质进行核磁共振氢谱(1H-NMR)和碳谱(13C-NMR)分析,溶剂采用CDCl3。 1.5 吲哚产生动态取Aeroto-AUH-JLC140的种子液400 µL接种于装有4 mL新鲜BHI液体培养基的带盖螺口玻璃试管中,于37℃普通生化培养箱中静置培养。分别在接种后3、6、9、12、15、18和21 h取样,样品的萃取及高效液相色谱检测方法同1.2,试验重复3次。分别记录不同取样时间吲哚的出峰面积,根据吲哚标准曲线绘制Aeroto-AUH-JLC140的吲哚产生动态。

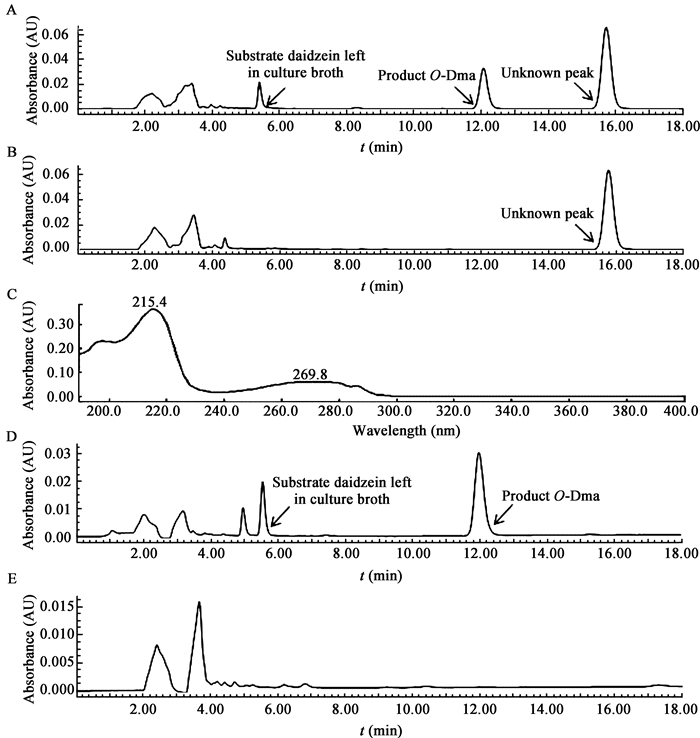

1.6 吲哚抗氧化活性测定 1.6.1 DPPH自由基清除试验: 1, 1-二苯基-2-苦味酰基自由基(1, 1-Diphenyl-2-picrylhydrazyl radical,DPPH)是一种稳定的单电子自由基,在517 nm下有强的吸收。以乙醇作为溶剂,以不加吲哚的比色管为对照,用紫外可见分光光度计进行测定。具体操作按本实验室以往报道的方法进行[15],反应时间和温度稍有改进。具体方法为:取1 mL用乙醇溶解的样品加到比色管中,再与0.5 mL DPPH (0.4 mmol/L)混匀,在20℃黑暗环境中分别反应1、24、48和96 h,在517 nm下测定吸光度,根据对照和样品的吸光度计算清除率。清除率的计算公式为:自由基清除率(%)=(1−Ai/Ao)×100,其中Ai为将待测样品加入DPPH反应体系后测得的吸光度,Ao为不加待测样品(用100%乙醇替代样品)时DPPH反应体系本身的吸光度。所用吲哚浓度分别为0.05、0.10、0.20、0.40和0.50 mmol/L。试验至少重复3次,数据用平均值±标准误表示,统计分析用one-way ANOVA来比较。显著性以“*”(P < 0.05)或“**”(P < 0.01)表示。 1.6.2 氧化-还原电位的测定: 以盛有12 mL BHI新鲜液体培养基(培养基高度约4 cm)的带盖螺口玻璃试管(试管口直径2.5 cm)为对照,向试管中分别添加终浓度为0.1 mmol/L和0.2 mmol/L的吲哚,将螺口试管静置在37℃普通生化培养箱内,静置1、12、24和48 h后,用酸度计测定不同试管内的氧化-还原电位。 2 结果与分析 2.1 原出发菌株和耐氧突变株发酵液未知物质检测经高效液相检测发现,不论是否添加底物黄豆苷原,在耐氧突变株Aeroto-AUH-JLC140的发酵液中,均在保留时间15.8 min处检测到一未知物质峰(图 1A和B),且图 1A和图 1B中未知物质峰的紫外吸收图谱完全一致,分别在215 nm和269 nm有最大紫外吸收(图 1C)。然而,对原出发菌株AUH-JLC140而言,不论是否添加底物黄豆苷原,在其发酵液中均未检测到未知物质峰(图 1D和E)。由于未知物质的产生与添加底物黄豆苷原无关,由此可以断定,耐氧突变株Aeroto-AUH-JLC140发酵液中的未知物质为该菌株产生的次生代谢产物。

|

| 图 1 未知物质高效液相色谱图 Figure 1 HPLC elution profiles of the unknown substance 注:A:耐氧突变株Aeroto-AUH-JLC140在添加底物黄豆苷原时未知物质峰的高效液相色谱图;B:耐氧突变株Aeroto-AUH-JLC140不添加黄豆苷原时未知物质峰的高效液相色谱图;C:未知物质峰紫外吸收图谱;D:原出发菌株AUH-JLC140在添加黄豆苷原时的高效液相色谱图;E:原出发菌株AUH-JLC140不添加黄豆苷原时的高效液相色谱图. Note: A: HPLC elution profile of the unknown peak produced by the oxygen-tolerant mutant strain Aeroto-AUH-JLC140 when incubated with the substrate daidzein; B: HPLC elution profile of the unknown peak produced by the oxygen-tolerant mutant strain Aeroto-AUH-JLC140 when daidzein was not added; C: UV spectrum of the unknown substance; D: HPLC elution profile of the culture broth extract of the original bacterium strain AUH-JLC140 when incubated with daidzein; E: HPLC elution profile of the culture broth extract of the original bacterium strain AUH-JLC140 when daidzein was not added. |

|

|

由于耐氧突变株所产未知物质的紫外吸收图谱(图 1C)与吲哚的[16]完全吻合,因此对未知物质进行了吲哚显色反应验证。结果发现,在Aeroto-AUH-JLC140培养液萃取物中加入一定量Kovac试剂后,可明显观察到玫瑰红色,表明Aeroto-AUH-JLC140在其生长过程中可能产生了吲哚。

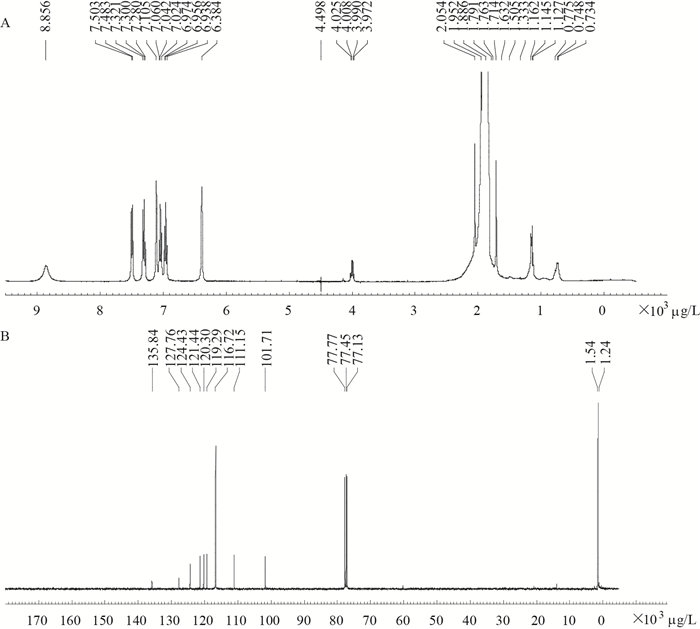

为确定未知物质的分子量,将分离纯化后的未知物质进行质谱分析(ESI-MS),发现其[M-H]-为116,因此确定Aeroto-AUH-JLC140所产未知物质的分子量应为117,这恰与吲哚(C8H7N)的分子量一致。为进一步准确鉴定未知物质的化学结构,将未知物质分别进行核磁共振氢谱(1H-NMR)和碳谱(13C-NMR)测定,结果如图 2A (1H-NMR)和图 2B (13C-NMR)所示。

|

| 图 2 未知物质核磁共振氢谱和碳谱图 Figure 2 1H NMR and 13C NMR spectra of the unknown substance 注:A:耐氧突变株Aeroto-AUH-JLC140所产未知物质的核磁共振氢谱图;B:核磁共振碳谱图. Note: A: 1H NMR spectrum of the unknown substance produced by the oxygen-tolerant mutant strain Aeroto-AUH-JLC140; B: 13C NMR spectrum of the unknown substance. |

|

|

未知物质核磁共振氢谱的解析结果为:1H NMR (CDCl3,400 MHz):δ6.38 (1H,d,J=2.88 Hz,H-3),6.93−6.97 (1H,t,J=7.13 Hz,H-5),7.02−7.06 (1H,t,J=7.12 Hz,H-6),7.10 (1H,t,J=2.88 Hz,H-2),7.30−7.32 (1H,d,J=8.02 Hz,H-7),7.48−7.50 (1H,d,J=7.82 Hz,H-4),8.85 (1H,N-H)。该结果与已报道的吲哚的氢谱解析结果一致[17]。

未知物质核磁共振碳谱的解析结果为:13C NMR:δ135.84 (C-9),127.76 (C-8),124.43 (C-2),121.44 (C-6),120.30 (C-4),119.29 (C-5),111.15 (C-7),101.71 (C-3)。该结果与吲哚的碳骨架结构也完全相一致[18]。

因此,根据紫外吸收图谱、颜色反应、质谱以及核磁共振氢谱和碳谱的解析结果,最终将Aeroto-AUH-JLC140产生的未知物质鉴定为吲哚。

2.3 吲哚产生动态为了解Aeroto-AUH-JLC140在培养过程中何时开始产生吲哚及其产生量,对该耐氧突变株产吲哚的动态进行了测定,结果如图 3所示。由图 3可以看出,Aeroto-AUH-JLC140在接种后6 h开始有吲哚生成,在6 h之前检测到的少量吲哚应该为种子液中的吲哚(10%接种量);从6−15 h吲哚生成量几乎成直线上升,到15 h吲哚生成量达到最高,为19.89 mg/L;15−21 h吲哚量急剧降低,在培养时间21 h时,吲哚量下降为8.19 mg/L。

|

| 图 3 耐氧突变株Aeroto-AUH-JLC140的吲哚产生动态 Figure 3 Kinetics study of indole produced by the oxygen-tolerant mutant strain Aeroto-AUH-JLC140 |

|

|

|

| 图 4 不同浓度吲哚对DPPH自由基的清除能力比较 Figure 4 Comparison of the DPPH radical-scavenging capacity of indole at different concentrations |

|

|

| 放置时间 Laying time (h) |

BHI液体培养基 BHI liquid medium |

添加0.1 mmol/L吲哚 Add 0.1 mmol/L of indole to medium |

添加0.2 mmol/L吲哚 Add 0.2 mmol/L of indole to medium |

| 1 | −60.5 | −62.8 | −66.1 |

| 12 | −15.3 | −19.9 | −26.6 |

| 24 | 36.8 | 27.3 | 11.7 |

| 48 | 69.3 | 41.7 | 24.8 |

有关耐氧菌的耐氧机制,目前大多认为是菌体细胞能够产生SOD和过氧化物酶(但缺乏过氧化氢酶)。本研究发现,耐氧突变株Aeroto-AUH-JLC140可通过产生吲哚为菌株生长提供适宜的低氧微环境。菌株Bacillus alvei[19]、Klebsiella oxytoca[20]、Proteus vulgaris[21]、Porphyromonas gingivalis[22]、Fusobacterium nucleatum[23]、Prevotella intermedia[24]和Escherichia coli[25]均产生吲哚,但不同菌株以及同一菌株在不同培养条件下产吲哚量各不相同。有研究报道,大肠杆菌MG1655在LB培养基中产吲哚量为0.5−0.6 mmol/L,当向LB培养基中添加足量色氨酸后,该菌株产吲哚量竟高达4−5 mmol/L[25]。除大肠杆菌外,Sasaki-Imamura等还对具核梭杆菌(Fusobacterium nucleatum)和普雷沃菌(Prevotella sp.)等无芽孢革兰氏阴性厌氧菌的吲哚产量进行了定量分析。具核梭杆菌ATCC 25586在哥伦比亚培养基中产吲哚量为0.06 mmol/L[23],在BHI培养基中产吲哚产量为0.22 mmol/L;普雷沃菌属菌株在BHI培养基中产吲哚量为0.05−0.10 mmol/L[24]。本研究中的耐氧突变株Aeroto-AUH-JLC140产吲哚量为0.17 mmol/L,这一吲哚产量与具核梭杆菌的相近。DPPH自由基清除试验结果表明,浓度为0.1 mmol/L和0.2 mmol/L的吲哚均能有效清除DPPH自由基。此外,通过测定培养基氧化-还原电位还发现,添加吲哚的BHI液体培养基的氧化-还原电位比不添加吲哚的上升缓慢,添加高浓度(0.2 mmol/L)吲哚的BHI液体培养基的氧化-还原电位比添加低浓度(0.1 mmol/L)的上升缓慢,说明吲哚具有一定的抗氧化活性,而有关吲哚的抗氧化能力目前尚未见报道。

长期以来,吲哚一直作为具有恶臭气味的化学排斥物为人们所认知[26]。最新研究表明,吲哚可作为信号分子影响氨基酸代谢[17]、生物膜形成[23]、质粒维持[27]、药物运输[28]、菌株致病性[29]及多糖产生[30]等关键基因的表达。本实验室前期研究结果证实,当耐氧突变株Aeroto-AUH-JLC140在有空气氧条件下(即普通生化培养箱中培养)生长时,在菌体外壁会形成一层以多糖为主要成分的“保护膜”结构[13],这层“保护膜”结构可有效阻挡培养基溶氧进入菌体进而对菌体造成伤害。有关耐氧突变株Aeroto-AUH-JLC140形成的多糖“保护膜”结构是否也同样受到了吲哚的调控,尚有待进一步研究。

| [1] | Yu Q, Wang WW, Li AL, et al. The study of the effects of soybean isoflavone on antioxidation and bone morphology in ovariectomized rats[J]. Acta Anatomica Sinica , 2007, 38 (2) : 222–225. (in chinese) 余清, 王文蔚, 李安乐, 等. 大豆异黄酮对去卵巢大鼠抗氧化及骨形态学影响的研究[J]. 解剖学报 , 2007, 38 (2) : 222–225. |

| [2] | Zhou J, Wei HM, Rong R, et al. Effects of soy isoflavones on the invasion and metastasis of human breast cancer MCF-7 cells and its correlation with PPARγ[J]. Acta Nutrimenta Sinica , 2012, 34 (1) : 58–63. (in chinese) 周静, 韦红梅, 戎嵘, 等. 大豆异黄酮对人乳腺癌MCF-7细胞侵袭转移能力的影响及其与PPARγ的关系研究[J]. 营养学报 , 2012, 34 (1) : 58–63. |

| [3] | Sun Q, Xu JP, Xu HX, et al. Anti-tumor effect of soybean isoflavones[J]. Food Science and Technology , 2009, 34 (8) : 60–62. (in chinese) 孙权, 徐俊萍, 许惠仙, 等. 大豆异黄酮抗肿瘤作用的研究[J]. 食品科技 , 2009, 34 (8) : 60–62. |

| [4] | Potter SM, Baum JA, Teng H, et al. Soy protein and isoflavones: their effects on blood lipids and bone density in postmenopausal women[J]. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition , 1998, 68 (6) : 1375S–1379S. |

| [5] | Alekel DL, Germain AS, Peterson CT, et al. Isoflavone-rich soy protein isolate attenuates bone loss in the lumbar spine of perimenopausal women[J]. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition , 2000, 72 (3) : 844–852. |

| [6] | Anderson JW, Johnstone BM, Cook-Newell ME. Meta-analysis of the effects of soy protein intake on serum lipids[J]. The New England Journal of Medicine , 1995, 333 (5) : 276–282. DOI:10.1056/NEJM199508033330502 |

| [7] | Hur HG, Lay JO Jr, Beger RD, et al. Isolation of human intestinal bacteria metabolizing the natural isoflavone glycosides daidzin and genistin[J]. Archives of Microbiology , 2000, 174 (6) : 422–428. DOI:10.1007/s002030000222 |

| [8] | Wang XL, Hur HG, Lee JH, et al. Enantioselective synthesis of S-equol from dihydrodaidzein by a newly isolated anaerobic human intestinal bacterium[J]. Applied and Environmental Microbiology , 2005, 71 (1) : 214–219. DOI:10.1128/AEM.71.1.214-219.2005 |

| [9] | Wang XL, Zhang ZX, Li H, et al. Clostridium sp. AUH-JLC140 and application of the bacterium for biosynthesis of O-Desmethylangolensin: China, ZL201110367963.1[P]. 2012-03-28 (in Chinese) 王秀伶, 张志贤, 李慧, 等.梭菌AUH-JLC140及其在去氧甲基安哥拉紫檀素生物合成中的应用:中国, ZL201110367963.1[P]. 2012-03-28 |

| [10] | Kinjo J, Tsuchihashi R, Morito K, et al. Interactions of phytoestrogens with estrogen receptors alpha and beta (Ⅲ). Estrogenic activities of soy isoflavone aglycones and their metabolites isolated from human urine[J]. Biological & Pharmaceutical Bulletin , 2004, 27 (2) : 185–188. |

| [11] | Morito K, Hirose T, Kinjo J, et al. Interaction of phytoestrogens with estrogen receptors alpha and beta[J]. Biological & Pharmaceutical Bulletin , 2001, 24 (4) : 351–356. |

| [12] | Schmitt E, Dekant W, Stopper H. Assaying the estrogenicity of phytoestrogens in cells of different estrogen sensitive tissues[J]. Toxicology in Vitro , 2001, 15 (4/5) : 433–439. |

| [13] | Li H. Isolation, oxygen-tolerant domestication of isoflavone biotransforming bacteria and oxygen-tolerant mechanisms for the obtained oxygen-tolerant mutant[D]. Baoding: Master's Thesis of Agricultural University of Hebei, 2013 (in Chinese) 李慧.大豆异黄酮转化菌株的分离、耐氧驯化及耐氧机制研究[D].保定:河北农业大学硕士学位论文, 2013 |

| [14] | Dong XZ, Cai MY. Systematic Identification Manual of Common Bacteria[M]. Beijing: Science Press, 2001: 379 . (in chinese) 东秀珠, 蔡妙英. 常见细菌系统鉴定手册[M]. 北京: 科学出版社, 2001: 379 . |

| [15] | Liang XL, Wang XL, Li Z, et al. Improved in vitro assays of superoxide anion and 1, 1-diphenyl-2-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH) radical-scavenging activity of isoflavones and isoflavone metabolites[J]. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry , 2010, 58 (22) : 11548–11552. DOI:10.1021/jf102372t |

| [16] | Catalán J. The first UV absorption band for indole is not due to two simultaneous orthogonal electronic transitions differing in dipole moment[J]. Physical Chemistry Chemical Physics , 2015, 17 (19) : 12515–12520. DOI:10.1039/C5CP01170A |

| [17] | Wang D, Ding X, Rather PN. Indole can act as an extracellular signal in Escherichia coli[J]. Journal of Bacteriology , 2001, 183 (14) : 4210–4216. DOI:10.1128/JB.183.14.4210-4216.2001 |

| [18] | Panasenko AA, Caprosh AF, Radul OM, et al. 13C NMR spectra of some indole derivatives[J]. Russian Chemical Bulletin , 1994, 43 (1) : 60–63. DOI:10.1007/BF00699136 |

| [19] | Fenske JD, DeMoss RD. Substrate-protein interaction in tryptophanase from Bacillus alvei. Kinetic and spectral evaluations[J]. The Journal of Biological Chemistry , 1975, 250 (19) : 7554–7563. |

| [20] | Maslow JN, Brecher SM, Adams KS, et al. Relationship between indole production and differentiation of Klebsiella species: indole-positive and-negative isolates of Klebsiella determined to be clonal[J]. Journal of Clinical Microbiology , 1993, 31 (8) : 2000–2003. |

| [21] | Zakomirdina LN, Kulikova VV, Gogoleva OI, et al. Tryptophan indole-lyase from Proteus vulgaris: kinetic and spectral properties[J]. Biochemistry , 2002, 67 (10) : 1189–1196. |

| [22] | Yoshida Y, Sasaki T, Ito S, et al. Identification and molecular characterization of tryptophanase encoded by tnaA in Porphyromonas gingivalis[J]. Microbiology , 2009, 155 (3) : 968–978. DOI:10.1099/mic.0.024174-0 |

| [23] | Sasaki-Imamura T, Yano A, Yoshida Y. Production of indole from L-tryptophan and effects of these compounds on biofilm formation by Fusobacterium nucleatum ATCC 25586[J]. Applied and Environmental Microbiology , 2010, 76 (13) : 4260–4268. DOI:10.1128/AEM.00166-10 |

| [24] | Sasaki-Imamura T, Yoshida Y, Suwabe K, et al. Molecular basis of indole production catalyzed by tryptophanase in the genus Prevotella[J]. FEMS Microbiology Letters , 2011, 322 (1) : 51–59. DOI:10.1111/fml.2011.322.issue-1 |

| [25] | Li G, Young KD. Indole production by the tryptophanase TnaA in Escherichia coli is determined by the amount of exogenous tryptophan[J]. Microbiology , 2013, 159 (Pt 2) : 402–410. |

| [26] | Tso WW, Adler J. Negative chemotaxis in Escherichia coli[J]. Journal of Bacteriology , 1974, 118 (2) : 560–576. |

| [27] | Chant EL, Summers DK. Indole signalling contributes to the stable maintenance of Escherichia coli multicopy plasmids[J]. Molecular Microbiology , 2007, 63 (1) : 35–43. DOI:10.1111/mmi.2007.63.issue-1 |

| [28] | Hirakawa H, Inazumi Y, Masaki T, et al. Indole induces the expression of multidrug exporter genes in Escherichia coli[J]. Molecular Microbiology , 2005, 55 (4) : 1113–1126. |

| [29] | Anyanful A, Dolan-Livengood JM, Lewis T, et al. Paralysis and killing of Caenorhabditis elegans by enteropathogenic Escherichia coli requires the bacterial tryptophanase gene[J]. Molecular Microbiology , 2005, 57 (4) : 988–1007. DOI:10.1111/j.1365-2958.2005.04739.x |

| [30] | Mueller RS, Beyhan S, Saini SG, et al. Indole acts as an extracellular cue regulating gene expression in Vibrio cholerae[J]. Journal of Bacteriology , 2009, 191 (11) : 3504–3516. DOI:10.1128/JB.01240-08 |

2016, Vol. 43

2016, Vol. 43