扩展功能

文章信息

- 吴月红, 许学伟

- WU Yue-Hong, XU Xue-Wei

- 赤杆菌科微生物分类研究进展

- Advances in the taxonomy of Erythrobacteraceae

- 微生物学通报, 2016, 43(5): 1082-1094

- Microbiology China, 2016, 43(5): 1082-1094

- DOI: 10.13344/j.microbiol.china.150973

-

文章历史

- 收稿日期: 2015-11-25

- 接受日期: 2016-03-07

- 优先数字出版日期(www.cnki.net): 2016-03-18

赤杆菌科(Erythrobacteraceae)隶属于细菌域(Bacteria)、变形菌门(Proteobacteria)、α-变形菌纲(Alphaproteobacteria)、鞘脂单胞菌目(Sphingomonadales)。赤杆菌科微生物营好氧异养生长,具有独特的生理生化特征,在水生生态系统中具有特殊作用。

部分赤杆菌科菌株具有细菌叶绿素a,营好氧异养生长兼具光合作用功能,被视为好养不产氧光合异养菌(Aerobic anoxygenic phototrophic bacteria,AAPB)。它们通过细菌叶绿素a构成的光合反应中心利用光能作为异养代谢的能量补充,在全球海洋碳循环和能量代谢过程中发挥着重要作用,对其生理特征、地理分布及动态变化、生态功能研究已成为目前海洋生物学研究领域的热点方向之一[1-2]。

1 赤杆菌科分类研究历史目前赤杆菌科与鞘脂单胞菌科(Sphingomonadaceae)系统发育关系最近,共同隶属于鞘脂单胞菌目;其模式属为赤杆菌属(Erythrobacter)。赤杆菌属(Erythrobacter,Eba.)于1982年被提议成立,菌落颜色主要为赤色、橙色或粉色,细胞形态呈杆状[3]。Eba. longus是其模式种,于20世纪70年代被发现,营好氧化能异养生长,具有细菌叶绿素a和类胡萝卜素,但不具有光合自养能力,通过鞭毛运动[3-4]。紫杆菌属(Prophyrobacter,Pba.)成立于1993年,模式种为Pba. neustonensis[5]。细胞在不同生长环境下呈现杆形、多形态或球形,表面具有多纤维束状结构,超微结构与浮霉菌目较为相似;系统发育结果显示Pba. neustonensis与Eba. longus类聚在一起,具有较高的亲缘关系[5]。赤微杆菌属(Erythromicrobium,Emi.)是1992年被首次报道,最初分离自淡水环境,细胞表达多种类胡萝卜素,呈杆形或多形态,包括ʻEmi. sibiricumʼ、ʻEmi. ursincolaʼ、ʻEmi. ezovicumʼ、ʻEmi. hydrolyticumʼ和ʻEmi. ramosumʼ 5个非合格发表物种[6]。1994年,Emi.ramosum被合格发表,是目前赤微杆菌属内唯一的合格发表物种[7]。1997年Emi.sibiricum和Emi. ursincola被重新划分至Sandaracinobacter属和Erythromonas属[8]。ʻEmi. ezovicumʼ和ʻEmi. hydrolyticumʼ至今仍未合格发表。2005年,日本学者依据16S rRNA基因序列的系统发育分析结果建立了赤杆菌科,将鞘脂单胞菌目下的赤杆菌属、紫杆菌属和赤微菌属调整至赤杆菌科[9-10]。

交替赤杆菌属(Altererythrobacter,Aba.)于2007年由韩国学者描述[11]。在系统发育关系上,交替赤杆菌属与赤杆菌属具有较高的相似性,但隶属于不同分支;少量物种也曾在这两个属内进行调整,例如:Eba. luteolus最初被归类于赤杆菌属,后被重新划分至交替赤杆菌属(Aba. luteolus)。正黄球菌属(Croceicoccus,Cco.)于2009年由中国学者报道[12]。该属细菌具有类胡萝卜素,未发现细菌叶绿素a。袁其鹏属(Qipengyuania,Qpy.)于2015年被提议成立[13]。在系统发育关系上,该属细菌形成一支独立的分支;其 16S rRNA基因序列与赤杆菌科成员的相似性低于96.4%。

截止2015年10月,赤杆菌科合格发表6个属44个种(表 1)。此外,系统发育研究结果显示,非合格发表的柠檬酸微菌(Citromicrobium)隶属于赤杆菌科[14]。柠檬酸微菌能利用柠檬酸盐为唯一碳源而得名,具有类胡萝卜素和细菌叶绿素a。

| 属/种名 Genus and Species | 标准菌株 Type strain | 16S rRNA基因登录号 16S rRNA gene accession number | 来源和分离地 Source and Site | 参考文献 Reference |

| Genus Erythrobacter | ||||

| Eba. longus | OCh101T | AF465835 | 海藻,日本 | Shiba等,1982[4] |

| Eba. litoralis | T4T | AF465836 | 海洋蓝藻垫,荷兰 | Yurkov等,1994[7] |

| Eba. citreus | RE35F/1T | AF118020 | 地中海海水,法国 | Denner等,2002[15] |

| Eba. flavus | SW-46T | AF500004 | 东海海水,韩国 | Yoon等,2003[16] |

| Eba. aquimaris | SW-110T | AY461441 | 黄海潮滩海水,韩国 | Yoon等,2004[17] |

| Eba. vulgaris | 022-2-10T | AY706935 | 海洋无脊椎动物,中国 | Ivanova等,2005[18] |

| Eba. gaetbuli | SW-161T | AY562220 | 黄海潮滩,韩国 | Yoon等,2005[19] |

| Eba. seohaensis | SW-135T | AY562219 | 黄海潮滩,韩国 | Yoon等,2005[19] |

| Eba. gangjinensis | K7-2T | EU428782 | 海水,韩国 | Lee等,2010[20] |

| Eba. nanhaisediminis | T30T | FJ654473 | 中国南海沉积物,中国 | Xu等,2010[21] |

| Eba. pelagi | UST081027-248T | HQ203045 | 红海海水,以色列 | Wu等,2012[22] |

| Eba. marinus | HWDM-33T | HQ117934 | 黄海海水,韩国 | Jung等,2012[23] |

| Eba. odishensis | JA747T | HE680094 | 太阳能盐田沉积物,印度 | Subhash等,2013[24] |

| Eba. jejuensis | CNU001T | DQ453142 | 济州岛海水,韩国 | Yoon等,2013[25] |

| Eba. lutimaris | S-5T | KJ870094 | 黄海潮滩沉积物,韩国 | Jung等,2014[26] |

| Eba. atlanticus | s21-N3T | KP994305 | 深海沉积物,大西洋 | Zhuang等,2015[27] |

| Eba. luteus | KA37T | KP197673 | 红树林国家保护区,中国 | Lei等,2015[28] |

| Genus Altererythrobacter | ||||

| Aba. epoxidivorans | JCS350T | DQ304436 | 海洋冷泉区沉积物,日本 | Kwon等,2007[11] |

| Aba. luteolus | SW-109T | AY739662 | 黄海潮滩,韩国 | Kwon等,2007[11] |

| Aba. indicus | MSSRF26T | DQ399262 | 红树林野生水稻,印度 | Kumar等,2008[29] |

| Aba. marinus | H32T | EU726272 | 深海海水,印度洋 | Lai等,2009[30] |

| Aba. marensis | MSW-14T | FM177586 | 济州岛海水,韩国 | Seo等,2010[31] |

| Aba. dongtanensis | CCTCC AB 209199T | GU166344 | 崇明东滩湿地,中国 | Fan等,2011[32] |

| Aba. ishigakiensis | JPCCMB0017T | AB363004 | 石垣岛海洋沉积物,日本 | Matsumoto等,2011[33] |

| Aba. namhicola | KYW48T | FJ935793 | 海水,韩国 | Park等,2011[34] |

| Aba. aestuarii | KYW147T | FJ997597 | 海水,韩国 | Park等,2011[34] |

| Aba. xinjiangensis | S3-63T | HM028673 | 新疆沙漠,中国 | Xue等,2012[35] |

| Aba. troitsensis | JCM 17037T | AY676115 | 东海海胆,俄罗斯 | Nedashkovskaya等, 2013[36] |

| Aba. gangjinensis | KJ7T | JF751048 | 潮滩,韩国 | Jeong等,2013[37] |

| Aba. atlanticus | CGMCC 1.12411T | KC018454 | 深海沉积物,大西洋 | Wu等,2014[38] |

| Aba. xiamenensis | LY02T | KC520828 | 赤潮表层海水,中国 | Lei等,2014[39] |

| Aba. aestiaquae | HDW-31T | KJ658262 | 黄海海水,韩国 | Jung等,2014[40] |

| Aba. oceanensis | Y2T | KF924606 | 深海沉积物,太平洋 | Yang等,2014[41] |

| Genus Croceicoccus | ||||

| Cco. marinus | E4A9T | EF623998 | 深海沉积物,太平洋 | Xu等,2009[12] |

| Cco. naphthovorans | PQ-2T | KF145127 | 海洋生物膜,中国 | Huang等,2015[42] |

| Genus Erythromicrobium | ||||

| Emi. ramosum | E5T | AF465837 | 碱性泉的蓝藻垫,德国 | Yurkov等,1994[7] |

| Genus Porphyrobacter | ||||

| Pba. neustonensis | ACM 2844T | AB033327 | 富营养湖水,澳大利亚 | Fuerst等,1993[5] |

| Pba. tepidarius | OT3T | AB033328 | 热泉,日本 | Hanada等,1997[43] |

| Pba. sanguineus | A91T | AB021493 | 海洋环境,波罗的海 | Hiraishi等,2002[44] |

| Pba. cryptus | ALC-2T | AF465834 | 热泉,葡萄牙 | Rainey等,2003[45] |

| Pba. donghaensis | SW-132T | AY559428 | 东海海水,韩国 | Yoon等,2004[46] |

| Pba. dokdonensis | DSW-74T | DQ011529 | 海水,韩国 | Yoon等,2006[47] |

| Pba. colymbi | TPW-24T | AB702992 | 游泳池水,日本 | Furuhata等,2013[48] |

| Genus Qipengyuania | ||||

| Qpy. sediminis | M1T | KJ734993 | 青藏高原沉积物,中国 | Feng等,2015[13] |

赤杆菌科微生物为革兰氏阴性菌,营好氧异养生长。不产氧光合作用是目前赤杆菌科微生物与相近类群之间最显著的区别特征之一。

赤杆菌属为赤杆菌科模式属,目前有17个物种,模式种为Eba. longus。需钠生长,不降解淀粉和明胶,硝酸盐还原反应为阴性,不能利用甲醇作为碳源,普遍能利用葡萄糖、丙酮酸盐、乙酸盐、丁酸盐和谷氨酸盐作为单一碳源。有3个物种报道具有细菌叶绿素a,分别为:Eba. longus、Eba. litoralis和Eba. marinus。DNA G+C含量为58.2−67.7 mol%。

交替杆菌属由16个物种组成,模式种为Aba. epoxidivorans。多数物种无鞭毛,细胞呈杆状,最适生长温度范围为15−35 °C。菌落颜色呈黄色至橙红色,没有报道发现表达细菌叶绿素a。DNA G+C含量为54.5−67.2 mol%。

紫杆菌属由7个物种组成,模式种为Pba. neustonensis。细胞呈现多形态、杆状或球状,能运动。细胞表面能产生纤维状结构和漏斗状结构。能利用葡萄糖,不能利用柠檬酸盐和阿拉伯糖。能产生细菌叶绿素a。DNA G+C含量为63.8−66.8 mol%。

正黄球菌属只有2个物种,模式物种为Cco. marinus。具有类胡萝卜素,未发现细菌叶绿素a存在。无法在光照条件下厌氧生长。DNA G+C含量为61.7−64.5 mol%。

赤微球菌属只有一个物种,模式种为Emi. ramosum。细胞为杆状或多形态,通过鞭毛运动和二分法分裂。菌落呈橙色,具有类胡萝卜素和细菌叶绿素a。无法在光照条件下厌氧生长。DNA G+C含量为64 mol%。

袁其鹏属只有一个物种,模式种为Qpy. sediminis。无运动性,兼性好氧。细胞椭圆形或短杆状。DNA G+C含量为73.7 mol%。

总体而言,赤杆菌科微生物细胞无芽孢形成,细胞多呈杆状或者多形态。目前已发现的物种多数具有类胡萝卜素,菌落呈现赤色、橙色、红色和黄色等;部分物种已报道表达细菌叶绿素a,目前未见光能自养生长的报道。

2.2 化学分类特征赤杆菌科微生物主要呼吸醌类型为泛醌 10 (Q10) 。Aba. indicus具有少量泛醌9 (Q9) [29]。

赤杆菌科微生物各属之间主要脂肪酸组成无显著区别。大部分交替杆菌属、赤杆菌属和紫杆菌属最主要脂肪酸成分为C18:1-ω7c。Eba. pelagi、Eba. luteus、Aba. oceanensis和Pba. dokdonensis 4个物种的最主要脂肪酸成分为C17:1-ω6c;C18:1-ω7c也是其主要成分之一。正黄球菌属和袁其鹏属主要脂肪酸成分为C17:1-ω6c和C18:1-ω7c。赤微球菌属未见脂肪酸结果报道。

赤杆菌科微生物极性脂类型包括磷脂酰胆碱(PC)、磷脂酰甘油(PG)、磷脂酰乙醇胺(PE)、双磷脂酰甘油(DPG)、鞘糖脂(SGL)、未确定成分的氨基脂(AL)、未确定成分的磷脂(PL)等,但不同属种之间具有差异。目前赤杆菌属各物种均检测到PC;PG和PE在赤杆菌属内普遍存在(除E. gangjinensis未检测到PG和E. lutimaris未检测到PE)。此外,大部分菌株的主要极性脂成分还包括DPG、SGL、AL和PL等。交替杆菌属主要极性脂为PE、PG、DPG和SGL;部分菌株的主要极性脂成分还包括PC、AL、PL和未确定成分的糖脂(GL)等。紫杆菌属极性脂报道少,Pba. cryptus主要极性脂成分为PE,Pba. sanguineus主要极性脂成分为SGL,未见其他物种相关报道。正黄球菌属主要极性脂为PC、PE、PG和SGL。袁其鹏属主要极性脂为DPG、PE、PG、SGL、PC和磷酸糖脂(PGL)。赤微球菌属则未见极性脂报道。

由此可见,赤杆菌科各属之间缺乏能显著区分的化学分类特征,一些物种之间在某些化学分类指标上的差异超过了一些属之间的差异。

2.3 基因组特征截止2015年10月,数据库共有10个赤杆菌科微生物标准菌株的基因组,其中5个基因组为完成图,其余为精细图。基因组信息统计见表 2。

| 物种 Species | 菌株名 Strain | 登录号 Accession number | 基因组长度 Genome length (Mb) | G+C含量 G+C content (mol%) | 基因数 Genes number | 核糖体RNA rRNA | 转运RNA tRNA | 染色体 Chromosomes | 框架片段 Scaffolds |

| Aba. atlanticus | 26DY36T | CP011452.2,CP011453.2 | 3.48 | 61.9 | 3 270 | 6 | 47 | 2 | 2 |

| Aba. epoxidivorans | CGMCC 1.7731T | CP012669.1 | 2.79 | 61.5 | 2 819 | 3 | 43 | 1 | 1 |

| Aba. marensis | KCTC 22370T | CP011805.1 | 2.89 | 64.7 | 2 721 | 3 | 45 | 1 | 1 |

| Cco. naphthovorans | PQ-2T | CP011770.1,CP011771.1,CP011772.1 | 3.86 | 62.6 | 3 840 | 3 | 46 | 3 | 3 |

| Eba. atlanticus | s21-N3T | CP011310.1 | 3.01 | 58.2 | 2 921 | 3 | 45 | 1 | 1 |

| Eba. litoralis | DSM 8509T | JMIXwswxtb-43-5-1082000.1 | 3.21 | 65.2 | 3 057 | 3 | 45 | − | 22 |

| Eba. longus | DSM 6997T | JMIWwswxtb-43-5-1082000.1 | 3.60 | 57.4 | 3 318 | 3 | 42 | − | 14 |

| Eba. marinus | KCTC 23554T | LDCPwswxtb-43-5-1082000.1 | 2.84 | 59.1 | 2 701 | 3 | 43 | − | 5 |

| Eba. gangjinensis | K7-2T | LBHCwswxtb-43-5-1082000.1 | 2.72 | 62.7 | 2 648 | 3 | 43 | − | 8 |

| Pba. cryptus | DSM 12079T | AUHCwswxtb-43-5-1082000.1 | 2.95 | 67.8 | 2 838 | 3 | 44 | − | 34 |

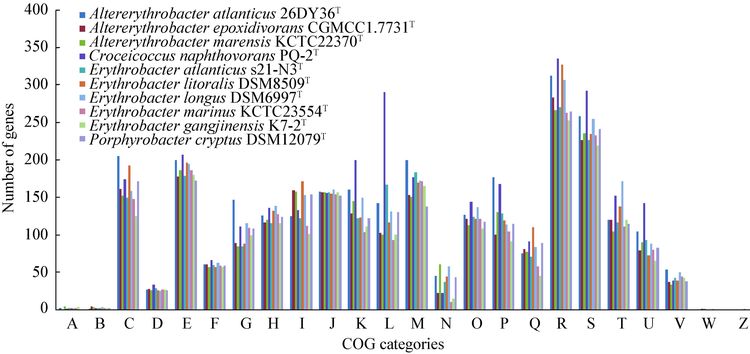

直系同源蛋白质组类群(Cluster of orthologous groups of proteins,COG)比较结果显示,10个菌株的COG 类群基因数分布相似(图 1);基因数量较多的类型包括:能量产生与保存类群(COG C)、氨基酸转运与代谢类群(COG E)以及两个未知功能类群(COG R和COG S)。氨基酸转运与代谢类群(COG E)基因的数量较碳转运与代谢类群(COG G)的高。值得注意的是,Cco. naphthovorans PQ-2T基因组转录(COG K)、复制/重组/修复相关(COG L)以及胞内运输分泌和膜泡运输(COG U)的基因数明显较其他菌株高;这可能与该菌株能适应多环芳烃污染环境,具有降解多环芳烃和产生N-乙酰基同型丝氨酸内酯能力有关。总体而言,赤杆菌科微生物能降解糖类、TCA循环中间产物、脂类和氨基酸,其在碳代谢方面具有多样性,基因组中发现了较完整的糖代谢ED和EM途径。

|

| 图 1 COG类群分布比较图 Figure 1 Comparison of COG categories among ten Erythrobacteraceae strains A:RNA加工和修饰;B:染色体结构和动态变化;C:能量产生和保存;D:细胞周期控制、细胞分裂和染色体分割;E:氨基酸转运和代谢;F:核苷酸转运和代谢;G:碳转运和代谢;H:辅酶转运和代谢;I:脂类转运和代谢;J:翻译、核糖体结构和合成;K:基因组转录;L:复制、重组、修复相关;M:细胞壁、细胞膜、胞外物质合成;N:细胞运动;O:翻译后修饰、蛋白质转换、调控;P:无机营养转运和代谢;Q:二级代谢生物合成,转运和分解作用;R:预测功能;S:未知功能;T:信号传导机制;U:胞内运输分泌和膜泡运输;V:防御机制;W:胞外结构;Z:细胞骨架. A: RNA processing and modification; B: chromatin structure and dynamics; C: Energy production and conversion; D: Cell cycle control,cell division,chromosome partitioning; E: Amino acid transport and metabolism; F: Nucleotide transport and metabolism; G: Carbohydrate transport and metabolism; H: Coenzyme transport and metabolism; I: Lipid transport and metabolism; J: Translation,ribosomal structure and biogenesis; K: Transcription; L: Replication,recombination and repair; M: Cell wall,membrane,envelope biogenesis; N: Cell motility; O: Posttranslational modification,protein turnover,chaperones; P: Inorganic transport and metabolism; Q: Secondary metabolites biosynthesis,transport and catabolism; R: General function prediction only; S: Function unknown; T: Signal transduction mechanisms; U: Intracellular trafficking,secretion and vesicular transport; V: Defense mechanisms; W: Extracellular structures; Z: Cytoskeleton. |

|

|

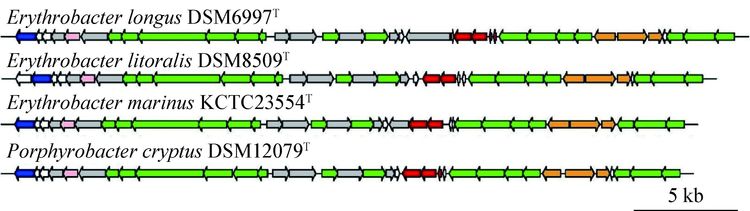

表型特征结果显示,Eba. longus DSM6997T、Eba. litoralis DSM8509T、Eba. marinus KCTC23554T和Pba. cryptus DSM12079T能产生细菌叶绿素a;进一步的基因组分析结果显示,这4株菌都具有完整的光合反应中心基因簇(PGC)(图 2)。该光合基因簇包括4个主要部分,编码参与细菌叶绿素a生物合成途径蛋白的bch基因,编码形成反应中心蛋白的puf基因,编码参与反应中心组装蛋白的puh基因以及编码参与类胡萝卜素合成蛋白的crt基因。目前推测,这4株菌可通过光合反应中心利用光能作为异养代谢的能量补充,但对其CO2固定能力还未得到最终确认,卡尔文循环关键酶(二磷酸核酮糖羧化酶)也未被发现。

|

| 图 2 光反应中心基因簇基因排列 Figure 2 Photosynthetic gene cluster structure and arrangement 绿色:细菌叶绿素a合成相关基因;红色:反应中心蛋白相关基因;粉色:反应中心组装相关基因;橙色:类胡萝卜素合成相关基因;灰色:调控及其他相关基因;白色:功能未知蛋白. Green: bch gene; Red: puf gene; Pink: puh gene; Orange: crt gene; Grey: regulators genes and other related genes; White: hypothetical protein. |

|

|

此外,菌株Aba. atlanticus 26DY36T分离自北大西洋中脊沉积物,具有抗重金属能力,能在高浓度Mn2+ (200 mmol/L)、Co2+ (2.0 mmol/L)、Cu2+ (1 mmol/L)、Zn2+ (1 mmol/L)、Hg2+ (0.1 mmol/L)或Cd2+ (0.5 mmol/L)溶液中生长。基因组分析结果显示,Aba. atlanticus 26DY36T编码32个与重金属抗性相关的基因,主要包括参与重金属离子外排的 3个蛋白家族、RND家族通透酶、CDF家族重金属转运蛋白和P型ATPase家族离子泵[49]。

Aba. epoxidivorans CGMCC 1.7731T分离自添加苯并芘作为碳源和能源的海洋沉积物,其具有22个基因与苯并芘降解通路相关,其可能在修复多环芳烃化合物污染的环境研究中发挥作用[50]。

3 赤杆菌科微生物生态分布 3.1 物种标准菌株的分离环境赤杆菌科成立之初,标准菌株主要分离自海藻[4, 7]、海水[15-17, 46]、淡水[5, 44]和热泉[43, 45]。随着赤杆菌科物种数量的增多,一些分离于其他环境的标准菌株也陆续被报道。截止2015年10月,所有赤杆菌属和正黄球菌属标准菌株均分离自海洋环境,包括海水、沉积物、海洋无脊椎动物和船舶附着微生物菌席等;交替杆菌属标准菌株主要来源于海洋环境,除了来自野生水稻根系的Aba. indicus和来自沙漠的Aba. xinjiangensis;紫杆菌属标准菌株分离自淡水、海水及含盐热泉环境;赤微杆菌属和袁其鹏属均只包含单一物种,标准菌株分离自淡水和土壤环境。显然,海洋环境是赤杆菌科微生物的主要来源(占总菌种数的79.5%),且以近海和大洋表层为主。

3.2 微生物栖息环境多样性依据历史文献、数据库资料及实验室分离培养菌株信息显示,近海、大洋和极地水体与沉积物环境以及一些特殊的陆地生境发现了赤杆菌科微生物的存在。赤杆菌属微生物自然分布范围广、栖息环境多样。当前其标准菌株都来源于海洋环境,但在一些非海洋环境中也发现了赤杆菌属微生物踪迹,例如:苏打池(FN395246) 、生物膜(JN594622) 、藻类培养液(DQ486511) 、莫高窟洞穴(JN244985) 、古盐矿(EF177676) 和磁铁矿排水系统(HQ652571) 等。交替赤杆菌属微生物主要来源于海洋环境,GenBank数据库显示在火山泥(FN397680) 、南极水生微生物菌席(FR772131) 、植物根系(GQ476825) 和田间土壤(JN848799) 等环境中也存在着此类微生物;此外,能降解多环芳烃和原油的交替赤杆菌(GQ505272) 也从深海沉积环境中被分离富集。紫杆菌属微生物栖息环境非常复杂,包括地表水、海水、尾矿砂(JQ429465) 、海上空气样品(GQ484916) 、活性碳过滤器(DQ884358) 、重油和重金属污染土壤(HQ588835) 、叠层石(EF150743) 、生物发酵池(GQ246725) 、注射液(AM236300) 、南极水生微生物菌席(FR772128) 、河口(AY788979) 、饮用水(JN547328) 、橡树叶(EF685171) 和古盐矿(EF177679) 等环境。未合格发表的ʻPba. meromictiusʼ分离自硫酸钠占主要成分的湖[51]。目前已报道的正黄球菌属、赤微杆菌属和袁其鹏属成员较少,其生境较为单一。然而,在火山泥(FN397674) 和砷污染土壤(AFI42455) 环境中也发现了赤微杆菌属的 存在。

3.3 赤杆菌科AAPB生态功能及其水体分布特征目前在紫杆菌属、赤微菌属、3个赤杆菌属物种(Eba. longus、Eba. litoralis和Eba. marinus)及非合格发表的柠檬酸微菌属发现了细菌叶绿素a的存在,它们均属于AAPB。

AAPB以细菌叶绿素a作为主要的光合色素;与紫色非硫细菌不同,其为好氧微生物[52];当有机碳源缺少时,AAPB可利用光能作为异养代谢的能量补充。有研究表明,赤杆菌属物种是大洋上层水体中主要的AAPB,在大洋真光层的碳循环过程中发挥着重要作用[53-55](Fenchel,2001; Shiba et al.,1991) 。非培养研究也发现,在太平洋、大西洋、印度洋以及中国东海和南海的上层水体中,约四分之一的核酸序列为赤杆菌属与玫瑰杆菌属序列[56]。然而,也有部分研究结果与上述结论不一致。例如:太平洋近岸与离岸水域样品中,只有一个站位赤杆菌属微生物占优[57];中北太平洋蒙特利湾水体中也未发现与赤杆菌属相似的基因序列[58]。AAPB是一个微生物功能类群,大洋水体中的AAPB由多种细菌类群组成,赤杆菌科微生物也是其重要成员之一,但随着区域和季节不同,AAPB优势类群类型可能会发生变化。

4 赤杆菌科微生物资源的应用赤杆菌科微生物具有生物降解、产类胡萝卜素,产细胞毒素和产酶等功能。在环境修复、食品工程以及生物医药等领域都具有重要应用价值。

(1) 具有降解有害化合物(烃类、芳香族以及卤化物)的能力。威望号油轮溢油事件(Prestige oil spill)一年后的石油污染沙石中检测到赤杆菌属微生物在链烷烃降解过程中发挥了重要作用[59]。无机营养对石油降解过程的影响研究中,Eba. longus和Eba. citreus是优势种[60]。在富营养的热带海洋环境中分离获得一株交替赤杆菌属菌株,其具有降解石油芳香族化合物的能力,在石油污染环境的生物修复过程中具有应用潜力[61]。紫杆菌属的菌株Oxy6表现出降解卤化物的能力,该菌株还能氧化苯甲醇、苯甲醛、苯甲酸、邻苯二酚和甲基邻苯二酚等[62]。亚碲酸化合物对生物具有毒性;部分赤杆菌属和赤微菌属菌株具有氧化亚碲酸盐并形成碲晶体的能力从而降低环境中的亚碲酸化合物浓度,它们在亚碲酸盐污染环境的生物修复过程中具有应用潜力[63]。

(2) 产类胡萝卜素。赤杆菌科微生物能产生类胡萝卜素,具有明显的色素沉积,在食品工程领域具有应用前景[5, 7, 11-13, 64-66]。Eba. longus能产生近二十种不同的类胡萝卜素[64]。赤杆菌属菌株1436具有较强的虾青素生产能力,虾青素占总色素的35%,甚至更多;目前该菌株已申请专利,作为添加剂应用于食品和饲料中。

(3) 产细胞毒素。分离自红树林沉积物的赤杆菌属菌株SNB-035能够产生细胞毒素化合物,对非小细胞肺癌细胞株有毒性[67-68],在医药领域具有一定应用前景。

(4) 产环氧化物水解酶。Eba. litoralis HTCC2594环氧化合物水解酶具有水解氧化苯乙烯活性[69]。Eba. sp. JCS358和Aba. epoxidivorans JCS350T均具有水解环氧化合物的能力,其中前者对底物具有较好的选择性[10, 70]。鉴于赤杆菌科微生物的环氧化物水解酶对于环氧化合物异构体具有选择性,其在生物制药行业具有良好的应用前景。

5 赤杆菌科微生物分类研究趋势 5.1 分类问题和难题最初,依据16S rRNA基因序列相似性、光合反应中心类型、类胡萝卜素组成和栖息环境等方面差异,赤杆菌科被分成3个属。随后,新的属和种被不断补充进赤杆菌科,并由此产生了一系列分类问题和难题。

(1) 全物种系统发育树(All-Species Living Tree)[71-72]系统发育分析结果显示,赤杆菌科微生物为多系组成。Cco. marinus、Aba. xinjiangensis、Aba. dongtanensis、Aba. troitsensis和Qpy. sediminis为独立分支,聚类于鞘脂单胞菌科类群。Aba. aestuarii、Aba. namhicola和Aba. atlanticus聚类在赤杆菌科和鞘脂单胞菌科之外。(2) 部分赤杆菌属物种的分类学地位需重新评估。赤杆菌属一些物种与其他属成员类聚在一起,例如:Eba. litoralis和Eba. jejuensis (图 3)。(3) 紫杆菌属成员栖息环境已发生改变,与最初的分类学依据背离。最初认为紫杆菌属成员都来自地表水或热泉等陆地生态环境,近年来发现的Pba. dokdonensis和Pba. donghaensis栖息环境为海水。(4) 色素组成差异作为划分属的关键依据值得商榷。传统分类学观点认为,赤微菌属与紫杆菌属最大差异在于后者缺少一种类胡萝卜素(玉米黄素),然而紫杆菌属新成员Pba. colymbi也缺乏这一类色素;此外,在系统发育树上赤微菌属已在紫杆菌属分支中。(5) 交替赤杆菌属为多系组成,背离该属成立之初的分类学标准。2007年 ,韩国学者提议成立由单系组成的交替赤杆菌属,然而依据目前16S rRNA基因序列构建的系统发育树显示,交替赤杆菌属3个新成员Aba. xinjiangensis、Aba.troitsensis和Aba. dongtanensis形成了相对独立的分支(图 3)。(6) 赤杆菌科各属之间缺乏能显著区分的化学分类特征。

|

| 图 3 基于16S rRNA基因序列构建的赤杆菌科微生物系统发育树 Figure 3 Phylogenetic tree of the family Erythrobacteraceae based on the 16S rRNA gene sequence |

|

|

赤杆菌科微生物本身特点造成现有成熟的分类技术方法不能完全解决其分类问题。需采用新技术方法,寻找分类新指标,完善分类标准并提出分类新体系,从而达到正确、有效、快速鉴定与分类的目标。

基于基因组测序技术发展起来的新型微生物分类学方法,为基因组时代微生物分类学研究带来希望的曙光,也为基于基因组学赤杆菌科分类研究提供可能。目前一些微生物分类学者已在其他微生物类群分类研究过程中采用基因组信息(包括代谢通路和关键酶基因)代替传统耗时、昂贵和结果易变的生理生化指标测定[73]。采用平均核苷酸一致值(Average nucleotide identity value,ANI值)代替传统DNA杂交法,ANI值也有望成为基因组研究时代区分微生物基因种的黄金标准[74-76]。此外,多位点序列分析技术(Multilocus sequence analysis,MLSA)也已逐渐应用于一些微生物的分类学研究中,包括弧菌和芽孢杆菌等[71];采用该技术能提高不同分类单元分歧度,避免16S rRNA基因异质性多拷贝干扰分类结论。

5.3 分离技术方法探索赤杆菌科微生物在多种生境中广泛分布,近年来大量菌株的分离与一些新属种数量增加迅速,显示出其物种资源非常丰富,自然界中一些新的分类单元有待认识。一些新型的微生物分类技术方法的探索与应用,将会提高未来赤杆菌科微生物新分类单位的发现效率。

普通培养过程中代时快或优势菌株掩盖其他类群是某些未培养微生物难分离培养的一个重要因素。目前已发展了一些新分离技术,例如极限稀释和单细胞技术,其核心是获得个体细胞。在一些海洋真光层环境中,SAR11类群占据数量上的优势,通过极限稀释技术首次分离获得SAR11菌株[77]。单细胞技术在菌株分离中的应用主要聚焦于获得单个代表性细胞基因组信息,通过分析预测目标菌的生长条件,进而探索其可能的培养条件[78-80]。这些技术可应用于环境中优势赤杆菌的分离培养。此外,人工模拟培养环境缺乏某些微生物生长因子,也是影响分离培养效率的重要原因之一。扩散室(Diffusion chamber)培养技术[81]是通过模拟采样环境持续提供营养物质和生长因子的一种技术,其与传统固体培养基培养技术相比,效率提高了近千倍,观察到难培养细菌门类TM7的细胞生长[82]。改进后的分离芯片(Ichip)技术可将扩散室微型化,与传统技术相比,该技术获得的微生物新类型更多[83]。

6 小结赤杆菌科是一类重要的微生物,其来源广泛,主要分布于海洋、湖泊等水体环境,在全球海洋碳循环和能量代谢过程中发挥着重要作用,在环境修复、食品工程和生物医药等领域也具有应用价值。过去十年来,我国学者围绕赤杆菌资源收集、分类学、生态学及应用开展了一些研究工作,发表了新属两个新种13个,中国海洋微生物菌种保藏管理中心收集保藏了赤杆菌科微生物近600株,为后续研究工作提供了良好的基础。目前赤杆菌科还存在一些分类方面的问题,对其生物地理分布、系统发育、物种进化方面的认识仍待加深。

未来赤杆菌科分类学研究中,多种技术方法结合是发展趋势,例如采用基因组信息进行表型预测、多位点序列分析及ANI值比较等,再综合传统分类学数据,解决赤杆菌科分类现有问题,建立新的分类体系。基因组测序技术和新分类技术的应用,加速了赤杆菌科微生物分类研究进程及新分类单元发现,有助于加深赤杆菌科微生物系统与进化方面的认识。

| [1] | Jiao NZ, Sieracki ME, Zhang Y, et al. Aerobic anoxygenic phototrophic bacteria and their roles in marine ecosystems[J]. Chinese Science Bulletin, 2003, 48 (6): 530–534. (in chinese) 焦念志, SierackiME, 张瑶, 等. 好氧不产氧光合异养细菌及其在海洋生态系统中的作用[J]. 科学通报, 2003, 48 (6):530–534. |

| [2] | Jiao NZ. Carbon fixation and sequestration in the ocean, with special reference to the microbial carbon pump[J]. Scientia Sinica (Terrae), 2012, 42 (10): 1473–1486. (in chinese) 焦念志. 海洋固碳与储碳——并论微型生物在其中的重要作用[J]. 中国科学: 地球科学, 2012, 42 (10):1473–1486. |

| [3] | Shiba T, Simidu U, Taga N. Distribution of aerobic bacteria which contain bacteriochlorophyll a[J]. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 1979, 38 (1): 43–45. |

| [4] | Shiba T, Simidu U. Erythrobacter longus gen. nov., sp. nov., an aerobic bacterium which contains bacteriochlorophyll a[J]. International Journal of Systematic Bacteriology, 1982, 32 (2): 211–217. |

| [5] | Fuerst JA, Hawkins JA, Holmes A, et al. Porphyrobacter neustonensis gen. nov., sp. nov., an aerobic bacteriochlorophyll-synthesizing budding bacterium from fresh water[J]. International Journal of Systematic Bacteriology, 1993, 43 (1): 125–134. |

| [6] | Yurkov V, Gorlenko VM, Kompantseva EI. A new type of freshwater aerobic orange-coloured bacterium, Erythromicrobium gen. nov. containing bacteriochlorophyll a[J]. Microbiology, 1992, 61 (2): 169–172. |

| [7] | Yurkov V, Stackebrandt E, Holmes A, et al. Phylogenetic positions of novel aerobic, bacteriochlorophyll a-containing bacteria and description of Roseococcus thiosulfatophilus gen. nov., sp. nov., Erythromicrobium ramosum gen. nov., sp. nov., and Erythrobacter litoralis sp. nov.[J]. International Journal of Systematic Bacteriology, 1994, 44 (3): 427–434. |

| [8] | Yurkov V, Stackebrandt E, Buss O, et al. Reorganization of the Genus Erythromicrobium: Description of “Erythromicrobium sibiricum” as Sandaracinobacter sibiricus gen. nov., sp. nov., and of “Erythromicrobium ursincola” as Erythromonas ursincola gen. nov., sp. nov.[J]. International Journal of Systematic Bacteriology, 1997, 47 (4): 1172–1178. |

| [9] | Lee KB, Liu CT, Anzai Y, et al. The hierarchical system of the ‘Alphaproteobacteria’: description of Hyphomonadaceae fam. nov., Xanthobacteraceae fam. nov. and Erythrobacteraceae fam. nov.[J]. International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology, 2005, 55 (5): 1907–1919. |

| [10] | Yabuuchi E, Kosako Y, Order IV. Sphingomonadales ord. nov. [A]//Brenner DJ, Krieg NR, Staley JT. Bergeyʼs Manual of Systematic Bacteriology: Volume Two, Part C, the Alpha-, Beta-, Delta-, and Epsilonproteobacteria)[M]. 2nd edition. New York: Springer, 2005: 230-233 |

| [11] | Kwon KK, Woo JH, Yang SH, et al. Altererythrobacter epoxidivorans gen. nov., sp. nov., an epoxide hydrolase-active, mesophilic marine bacterium isolated from cold-seep sediment, and reclassification of Erythrobacter luteolus Yoon et al. 2005 as Altererythrobacter luteolus comb. nov.[J]. International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology, 2007, 57 (10): 2207–2211. |

| [12] | Xu XW, Wu YH, Wang CS, et al. Croceicoccus marinus gen. nov., sp. nov., a yellow-pigmented bacterium from deep-sea sediment, and emended description of the family Erythrobacteraceae[J]. International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology, 2009, 59 (9): 2247–2253. |

| [13] | Feng XM, Mo YX, Han L, et al. Qipengyuania sediminis gen. nov., sp. nov., a member of the family Erythrobacteraceae, isolated from subterrestrial sediment[J]. International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology, 2015, 65 (10): 3658–3665. |

| [14] | Yurkov VV, Krieger S, Stackebrandt E, et al. Citromicrobium bathyomarinum, a novel aerobic bacterium isolated from deep-sea hydrothermal vent plume waters that contains photosynthetic pigment-protein complexes[J]. Journal of Bacteriology, 1999, 181 (15): 4517–4525. |

| [15] | Denner EBM, Vybiral D, Koblížek M, et al. Erythrobacter citreus sp. nov., a yellow-pigmented bacterium that lacks bacteriochlorophyll a, isolated from the western Mediterranean Sea[J]. International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology, 2002, 52 (5): 1655–1661. |

| [16] | Yoon JH, Kim H, Kim IG, et al. Erythrobacter flavus sp. nov., a slight halophile from the East Sea in Korea[J]. International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology, 2003, 53 (4): 1169–1174. |

| [17] | Yoon JH, Kang KH, Oh TK, et al. Erythrobacter aquimaris sp. nov., isolated from sea water of a tidal flat of the Yellow Sea in Korea[J]. International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology, 2004, 54 (6): 1981–1985. |

| [18] | Ivanova EP, Bowman JP, Lysenko AM, et al. Erythrobacter vulgaris sp. nov., a novel organism isolated from the marine invertebrates[J]. Systematic and Applied Microbiology, 2005, 28 (2): 123–130. |

| [19] | Yoon JH, Oh TK, Park YH. Erythrobacter seohaensis sp. nov. and Erythrobacter gaetbuli sp. nov., isolated from a tidal flat of the Yellow Sea in Korea[J]. International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology, 2005, 55 (1): 71–75. |

| [20] | Lee YS, Lee DH, Kahng HY, et al. Erythrobacter gangjinensis sp. nov., a marine bacterium isolated from seawater[J]. International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology, 2010, 60 (6): 1413–1417. |

| [21] | Xu MS, Xin YH, Yu Y, et al. Erythrobacter nanhaisediminis sp. nov., isolated from marine sediment of the South China Sea[J]. International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology, 2010, 60 (9): 2215–2220. |

| [22] | Wu HX, Lai PY, Lee OO, et al. Erythrobacter pelagi sp. nov., a member of the family Erythrobacteraceae isolated from the Red Sea[J]. International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology, 2012, 62 (6): 1348–1353. |

| [23] | Jung YT, Park S, Oh TK, et al. Erythrobacter marinus sp. nov., isolated from seawater[J]. International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology, 2012, 62 (9): 2050–2055. |

| [24] | Subhash Y, Tushar L, Sasikala C, et al. Erythrobacter odishensis sp. nov. and Pontibacter odishensis sp. nov. isolated from dry soil of a solar saltern[J]. International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology, 2013, 63 (12): 4524–4532. |

| [25] | Yoon BJ, Lee DH, Oh DC. Erythrobacter jejuensis sp. nov., isolated from seawater[J]. International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology, 2013, 63 (4): 1421–1426. |

| [26] | Jung YT, Park S, Lee JS, et al. Erythrobacter lutimaris sp. nov., isolated from a tidal flat sediment[J]. International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology, 2014, 64 (12): 4184–4190. |

| [27] | Zhuang LP, Liu Y, Wang L, et al. Erythrobacter atlanticus sp. nov., a bacterium from ocean sediment able to degrade polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons[J]. International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology, 2015, 65 (10): 3714–3719. |

| [28] | Lei XQ, Zhang HJ, Chen Y, et al. Erythrobacter luteus sp. nov., isolated from mangrove sediment[J]. International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology, 2015, 65 (8): 2472–2478. |

| [29] | Kumar NR, Nair S, Langer S, et al. Altererythrobacter indicus sp. nov., isolated from wild rice (Porteresia coarctata Tateoka)[J]. International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology, 2008, 58 (4): 839–844. |

| [30] | Lai QL, Yuan J, Shao ZZ. Altererythrobacter marinus sp. nov., isolated from deep seawater[J]. International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology, 2009, 59 (12): 2973–2976. |

| [31] | Seo SH, Lee SD. Altererythrobacter marensis sp. nov., isolated from seawater[J]. International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology, 2010, 60 (2): 307–311. |

| [32] | Fan ZY, Xiao YP, Hui W, et al. Altererythrobacter dongtanensis sp. nov., isolated from a tidal flat[J]. International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology, 2011, 61 (9): 2035–2039. |

| [33] | Matsumoto M, Iwama D, Arakaki A, et al. Altererythrobacter ishigakiensis sp. nov., an astaxanthin-producing bacterium isolated from a marine sediment[J]. International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology, 2011, 61 (12): 2956–2961. |

| [34] | Park SC, Baik KS, Choe HN, et al. Altererythrobacter namhicola sp. nov. and Altererythrobacter aestuarii sp. nov., isolated from seawater[J]. International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology, 2011, 61 (4): 709–715. |

| [35] | Xue XQ, Zhang KD, Cai F, et al. Altererythrobacter xinjiangensis sp. nov., isolated from desert sand, and emended description of the genus Altererythrobacter[J]. International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology, 2012, 62 (1): 28–32. |

| [36] | Nedashkovskaya OI, Cho SH, Joung Y, et al. Altererythrobacter troitsensis sp. nov., isolated from the sea urchin Strongylocentrotus intermedius[J]. International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology, 2013, 63 (1): 93–97. |

| [37] | Jeong SH, Jin HM, Lee HJ, et al. Altererythrobacter gangjinensis sp. nov., a marine bacterium isolated from a tidal flat[J]. International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology, 2013, 63 (3): 971–976. |

| [38] | Wu YH, Xu L, Meng FX, et al. Altererythrobacter atlanticus sp. nov., isolated from deep-sea sediment[J]. International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology, 2014, 64 (1): 116–121. |

| [39] | Lei XQ, Li Y, Chen ZR, et al. Altererythrobacter xiamenensis sp. nov., an algicidal bacterium isolated from red tide seawater[J]. International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology, 2014, 64 (2): 631–637. |

| [40] | Jung YT, Park S, Lee JS, et al. Altererythrobacter aestiaquae sp. nov., isolated from seawater[J]. International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology, 2014, 64 (12): 3943–3949. |

| [41] | Yang YL, Zhang GY, Sun ZL, et al. Altererythrobacter oceanensis sp. nov., isolated from the Western Pacific[J]. Antonie van Leeuwenhoek, 2014, 106 (6): 1191–1198. |

| [42] | Huang YL, Zeng YH, Feng H, et al. Croceicoccus naphthovorans sp. nov., a polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons-degrading and acylhomoserine-lactone-producing bacterium isolated from marine biofilm, and emended description of the genus Croceicoccus[J]. International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology, 2015, 65 (5): 1531–1536. |

| [43] | Hanada S, Kawase Y, Hiraishi A, et al. Porphyrobacter tepidarius sp. nov., a moderately thermophilic aerobic photosynthetic bacterium isolated from a hot spring[J]. International Journal of Systematic Bacteriology, 1997, 47 (2): 408–413. |

| [44] | Hiraishi A, Yonemitsu Y, Matsushita M, et al. Characterization of Porphyrobacter sanguineus sp. nov., an aerobic bacteriochlorophyll-containing bacterium capable of degrading biphenyl and dibenzofuran[J]. Archives of Microbiology, 2002, 178 (1): 45–52. |

| [45] | Rainey FA, Silva J, Nobre MF, et al. Porphyrobacter cryptus sp. nov., a novel slightly thermophilic, aerobic, bacteriochlorophyll a-containing species[J]. International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology, 2003, 53 (1): 35–41. |

| [46] | Yoon JH, Lee MH, Oh TK. Porphyrobacter donghaensis sp. nov., isolated from sea water of the East Sea in Korea[J]. International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology, 2004, 54 (6): 2231–2235. |

| [47] | Yoon JH, Kang SJ, Lee MH, et al. Porphyrobacter dokdonensis sp. nov., isolated from sea water[J]. International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology, 2006, 56 (5): 1079–1083. |

| [48] | Furuhata K, Edagawa A, Miyamoto H, et al. Porphyrobacter colymbi sp. nov. isolated from swimming pool water in Tokyo, Japan[J]. The Journal of General and Applied Microbiology, 2013, 59 (3): 245–250. |

| [49] | Wu YH, Cheng H, Zhou P, et al. Complete genome sequence of the heavy metal resistant bacterium Altererythrobacter atlanticus 26DY36T, isolated from deep-sea sediment of the North Atlantic Mid-ocean ridge[J]. Marine Genomics, 2015, 24 (Pt 3): 289–292. |

| [50] | Li ZY, Wu YH, Huo YY, et al. Complete genome sequence of a benzo[a]pyrene-degrading bacterium Altererythrobacter epoxidivorans CGMCC 1.7731T[J]. Marine genomics, 2016 (25): 39–41. |

| [51] | Rathgeber C, Yurkova N, Stackebrandt E, et al. Porphyrobacter meromictius sp. nov., an appendaged bacterium, that produces bacteriochlorophyll a[J]. Current Microbiology, 2007, 55 (4): 356–361. |

| [52] | Yurkov VV, Beatty JT. Aerobic anoxygenic phototrophic bacteria[J]. Microbiology and Molecular Biology Reviews: MMBR, 1998, 62 (3): 695–724. |

| [53] | Shiba T, Shioi Y, Takamiya KI, et al. Distribution and physiology of aerobic bacteria containing bacteriochlorophyll a on the East and West coasts of Australia[J]. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 1991, 57 (1): 295–300. |

| [54] | Fenchel T. Marine bugs and carbon flow[J]. Science, 2001, 292 (5526): 2444–2445. |

| [55] | Kolber ZS, Plumley FG, Lang AS, et al. Contribution of aerobic photoheterotrophic bacteria to the carbon cycle in the ocean[J]. Science, 2001, 292 (5526): 2492–2495. |

| [56] | Jiao NZ, Zhang Y, Zeng YH, et al. Distinct distribution pattern of abundance and diversity of aerobic anoxygenic phototrophic bacteria in the global ocean[J]. Environmental Microbiology, 2007, 9 (12): 3091–3099. |

| [57] | Ritchie AE, Johnson ZI. Abundance and genetic diversity of aerobic anoxygenic phototrophic bacteria of coastal regions of the pacific ocean[J]. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 2012, 78 (8): 2858–2866. |

| [58] | Béjà O, Suzuki MT, Heidelberg JF, et al. Unsuspected diversity among marine aerobic anoxygenic phototrophs[J]. Nature, 2002, 415 (6872): 630–633. |

| [59] | Alonso-Gutiérrez J, Figueras A, Albaigés J, et al. Bacterial communities from shoreline environments (Costa da Morte, Northwestern Spain) affected by the Prestige oil spill[J]. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 2009, 75 (11): 3407–3418. |

| [60] | Röling WFM, Milner MG, Jones DM, et al. Robust hydrocarbon degradation and dynamics of bacterial communities during nutrient-enhanced oil spill bioremediation[J]. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 2002, 68 (11): 5537–5548. |

| [61] | Teramoto M, Suzuki M, Hatmanti A, et al. The potential of Cycloclasticus and Altererythrobacter strains for use in bioremediation of petroleum-aromatic-contaminated tropical marine environments[J]. Journal of Bioscience and Bioengineering, 2010, 110 (1): 48–52. |

| [62] | Goodwin KD, Tokarczyk R, Stephens FC, et al. Description of toluene inhibition of methyl bromide biodegradation in seawater and isolation of a marine toluene oxidizer that degrades methyl bromide[J]. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 2005, 71 (7): 3495–3503. |

| [63] | Yurkov V, Jappe J, Vermeglio A. Tellurite resistance and reduction by obligately aerobic photosynthetic bacteria[J]. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 1996, 62 (11): 4195–4198. |

| [64] | Takaichi S, Shimada K, Ishidsu JI. Carotenoids from the aerobic photosynthetic bacterium, Erythrobacter longus: β-carotene and its hydroxyl derivatives[J]. Archives of Microbiology, 1990, 153 (2): 118–122. |

| [65] | Takaichi S, Shimada K, Ishidsu JI. Monocyclic cross-conjugated carotenal from an aerobic photosynthetic bacterium, Erythrobacter longus[J]. Phytochemistry, 1988, 27 (11): 3605–3609. |

| [66] | Takaichi S, Furihata K, Ishidsu JI, et al. Carotenoid sulphates from the aerobic photosynthetic bacterium, Erythrobacter longus[J]. Phytochemistry, 1991, 30 (10): 3411–3415. |

| [67] | Hu YC, MacMillan JB. Erythrazoles A-B, cytotoxic benzothiazoles from a marine-derived Erythrobacter sp.[J]. Organic Letters, 2011, 13 (24): 6580–6583. |

| [68] | Hu YC, Legako AG, Espindola APDM, et al. Erythrolic acids A-E, meroterpenoids from a marine-derived Erythrobacter sp.[J]. The Journal of Organic Chemistry, 2012, 77 (7): 3401–3407. |

| [69] | Woo JH, Hwang YO, Kang SG, et al. Cloning and characterization of three epoxide hydrolases from a marine bacterium, Erythrobacter litoralis HTCC2594[J]. Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology, 2007, 76 (2): 365–375. |

| [70] | Hwang YO, Kang SG, Woo JH, et al. Screening enantioselective epoxide hydrolase activities from marine microorganisms: detection of activities in Erythrobacter spp.[J]. Marine Biotechnology, 2008, 10 (4): 366–373. |

| [71] | Ludwig W, Strunk O, Westram R, et al. ARB: a software environment for sequence data[J]. Nucleic Acids Research, 2004, 32 (4): 1363–1371. |

| [72] | Yarza P, Richter M, Peplies J, et al. The all-species living tree project: a 16S rRNA-based phylogenetic tree of all sequenced type strains[J]. Systematic and Applied Microbiology, 2008, 31 (4): 241–250. |

| [73] | Amaral GRS, Dias GM, Wellington-Oguri M, et al. Genotype to phenotype: identification of diagnostic vibrio phenotypes using whole genome sequences[J]. International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology, 2014, 64 (2): 357–365. |

| [74] | Oren A, Garrity GM. Then and now: a systematic review of the systematics of prokaryotes in the last 80 years[J]. Antonie van Leeuwenhoek, 2014, 106 (1): 43–56. |

| [75] | Konstantinidis KT, Tiedje JM. Genomic insights that advance the species definition for prokaryotes[J]. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 2005, 102 (7): 2567–2572. |

| [76] | Richter M, Rosselló-Móra R. Shifting the genomic gold standard for the prokaryotic species definition[J]. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 2009, 106 (45): 19126–19131. |

| [77] | Rappé MS, Connon SA, Vergin KL, et al. Cultivation of the ubiquitous SAR11 marine bacterioplankton clade[J]. Nature, 2002, 418 (6898): 630–633. |

| [78] | Raghunathan A, Ferguson Jr HR, Bornarth CJ, et al. Genomic DNA amplification from a single bacterium[J]. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 2005, 71 (6): 3342–3347. |

| [79] | Thrash JC, Temperton B, Swan BK, et al. Single-cell enabled comparative genomics of a deep ocean SAR11 bathytype[J]. The ISME Journal, 2014, 8 (7): 1440–1451. |

| [80] | Lasken RS. Single-cell genomic sequencing using multiple displacement amplification[J]. Current Opinion in Microbiology, 2007, 10 (5): 510–516. |

| [81] | Kaeberlein T, Lewis K, Epstein SS. Isolating “uncultivable” microorganisms in pure culture in a simulated natural environment[J]. Science, 2002, 296 (5570): 1127–1129. |

| [82] | Ferrari BC, Binnerup SJ, Gillings M. Microcolony cultivation on a soil substrate membrane system selects for previously uncultured soil bacteria[J]. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 2005, 71 (12): 8714–8720. |

| [83] | Nichols D, Cahoon N, Trakhtenberg EM, et al. Use of ichip for high-throughput in situ cultivation of “uncultivable” microbial species[J]. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 2010, 76 (8): 2445–2450. |

2016, Vol. 43

2016, Vol. 43