扩展功能

文章信息

- 崔丙健, 孔晓, 金德才, 白志辉, 张洪勋

- CUI Bing-Jian, KONG Xiao, JIN De-Cai, BAI Zhi-Hui, ZHANG Hong-Xun

- 农村生活污水处理厂中阿米巴原虫的定量检测

- Quantitative detection of amebic protozoa from rural domestic wastewater treatment plant

- 微生物学通报, 2015, 42(5): 866-873

- Microbiology China, 2015, 42(5): 866-873

- 10.13344/j.microbiol.china.140882

-

文章历史

- 收稿日期: 2014-11-06

- 接受日期: 2015-02-27

- 优先数字出版日期(www.cnki.net): 2015-02-27

2.中国科学院大学资源与环境学院 北京 100049

3.青岛科技大学环境与安全工程学院 山东 青岛 266042

2. College of Resources and Environment, University of Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100049, China

3. College of Environment and Safety Engineering, Qingdao University of Science and Technology, Qingdao, Shandong 266042, China

自然界的土壤和各类水体中,存在多种利用吞噬作用方式以细菌、真菌和藻类为食的自由生活阿米巴原虫(free-living amoebae,FLA)[1, 2]。与其他环境源相比,污水中存在的阿米巴原虫更加普遍,其中棘阿米巴属(Acanthamoeba spp.)、哈曼属(Hartmannella spp.)、耐格里属(Naegleria spp.)的某些种是主要的致病性原虫[3],它们本身能够引发多种在人与动物中传播并导致严重甚至致命后果的疾病。棘阿米巴虫属的少数种能够引起免疫功能缺陷病人肉芽肿性阿米巴脑炎,主要通过水源性传播各类疾病如角膜炎、皮肤炎、慢性肉芽肿病变、窦炎、肺炎和组织疾病等[4, 5, 6]。分离自脑膜炎和支气管肺炎病人脑脊液中的哈曼属原虫是许多人类病原菌的宿主[7],并且能够与棘阿米巴虫共存引发角膜炎。

早期传统的培养方法被用来检测水生环境中的原虫,并基于它们的形态学特征利用生化和免疫学方法进行分类[8]。但传统培养方法营养要求高,需时较长(15 d左右)以及虫体形态多变,并且镜检设备和技术操作要求高导致难以对原虫种类进行准确鉴别。为了摒弃这种耗时费力的方法,在过去的数十年间,众多研究者对原虫的分子检测技术进行了广泛研究,如利用靶标rRNA寡核苷酸探针的荧光原位杂交技术(FISH)和PCR技术等,但都难以对水体中原虫的起始浓度定量评估[9, 10, 11]。荧光定量PCR技术由于其能够通过Ct值进行起始模板定量分析被用来检测环境中的原虫。Kao等[12]报道利用荧光定量PCR检测和定量河流、水处理厂及温泉水等各类环境水样中的棘阿米巴虫属,研究显示水样中总检出率达到14.2%,浓度范围(46.0−1.5)×104 cells/L。Kuiper等[13]定量分析地表水中军团菌的潜在宿主H. vermiformis,检测浓度范围在5−75 cells/L之间,不同地表水克隆序列间与参考菌株序列高度相似≥98%,表明H. vermiformis是淡水水体微生物群落的普遍组成部分。Magnet等[14]为了研究地中海气候不同类型水体中阿米巴原虫的出现率和季节性变化,采集了包括自来水厂、污水处理厂及河流流域共计223个水样进行定量分析。结果表明棘阿米巴原虫的检出率达到99.1%,但发现其并未呈现季节性分布。

阿米巴原虫除了自身致病性外,还可以成为多种病原菌的自然宿主和传播疾病的媒介[15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21],人类在从事生产活动中直接或间接暴露接触的机率不断增加。农村生活污水出水中除了富含满足作物生长需求的氮磷钾元素外,还含有大量微量元素及有机质能够改善土壤肥力并提高作物产量,作为一种替代可再生水源,其灌溉回用为农业发展带来了环境和经济效益。然而,农村生活污水的间接利用通常是未经处理或部分处理后直接汇入水库、河流及渠道作为补给农业灌溉水源,无论是间接还是有计划的污水回用项目均可能对公众构成潜在的健康风险。与污水回用有关的健康危害有两种:一是从事农业生产及附近居住人群的农村卫生安全问题;二是污水回用区域的产品污染以及人类在加工和消费过程中的感染风险。因此,水体环境中致病性原虫的检测和种群定量显得至关重要,农村生活污水中有关阿米巴原虫的研究报道较少。为了更好地了解原虫潜在的健康风险,本文以18S rRNA基因为靶标序列建立了BRYT Green® dye染料法实时荧光定量PCR方法特异性检测和定量农村生活污水中的棘阿米巴虫和哈曼虫。

1 材料与方法 1.1 水样的采集北京市怀柔区桥梓镇北宅村生活污水处理厂(40°20′N,116°33′E)。该污水处理厂采用膜-生物反应器工艺,处理后的水质指标达到北京市《水污染物排放标准》(DB11/307-2005)一级B标准,再生水主要用于街道和绿化浇洒、农田灌溉、景观以及生活区中水回用等。选取进水、调节池、好氧池、膜生物反应池和出水作为研究对象,现场使用雷磁DZB-718便携式多参数水质分析仪测量部分水质参数:温度、pH、电导率等。同时,利用无菌的聚丙烯瓶和高硼硅玻璃瓶收集水样1−5 L保存于4 °C,当日尽快送至测试公司(Pony,中国)测定水质参数并于实验室中检测指示菌等其他参数。

1.2 实验仪器与试剂便携式多参数水质分析仪(雷磁DZB-718),上海仪电科学仪器股份有限公司;高速离心机(H165-W),湖南湘仪离心机仪器有限公司;基因扩增仪(EDC-810),北京东胜创新生物科技有限公司;快速核酸提取仪(Fastprep-24),美国安培公司;凝胶成像系统(G:BOX),美国Syngene公司;核酸蛋白测定仪(ND-2000),美国ThermoFisher公司;电泳仪(BG-Power 600i),北京百晶生物技术有限公司;实时荧光定量PCR仪(tratagene Mx3005P),美国Agilent公司;Fast DNA SPIN Kit for Soil试剂盒,美国MP公司;50 bp Plus DNA Ladder,宝如亿(北京)生物技术有限公司;pGEM-T Easy载体,美国Promega公司;大肠杆菌感受态细胞(DH5α),北京博迈德基因技术有限公司;微孔滤膜(0.22 μm),美国Millipore公司。

1.3 实验方法

1.3.1 样品预处理及基因组

滤膜样品用无菌剪刀剪碎,然后同其他样品一起使用Fast DNA SPIN Kit for Soil试剂盒提取总基因组DNA,具体步骤参照试剂盒说明书。取5 μl基因组DNA溶液用1.0%的琼脂糖凝胶电泳检测提取效果,采用NanoDrop 2000测定浓度及纯度(A260/A280值应在1.8−2.0之间),然后保存于−20 °C备用。

1.3.2 PCR扩增产物的克隆与测序: 根据文献报道选用Acanthamoebaspp.和Hartmannella vermiformis 18S rDNA靶标引物做常规PCR扩增反应,引物序列分别为[13, 22]:AcantF900 (5′-CCCAGATCGTTTAC CGTGAA-3′),AcantR1100 (5′-TAAATATTAATGCC CCCAACTATCC-3′);Hv1227F (5′-TTACGAGGTCA GGACACTGT-3′),Hv1728R (5′-GACCATCCGGAG TTCTCG-3′)。50 μl PCR反应体系:10×PCR缓冲液(含20 mmol/L MgCl2) 5 μl,dNTPs (10 mmol/L) 4 μl,上下游引物(10 μmol/L)各1 μl,Taq DNA聚合酶(5 U/μl) 0.5 μl,DNA模板1 μl,无菌的ddH2O补至50 μl。PCR反应条件:95 °C 10 min;95 °C 30 s,62 °C 45 s,72 °C 30 s,35个循环;72 °C 10 min,4 °C保持。PCR扩增产物用1.0%的琼脂糖凝胶电泳检测目的条带大小(Acanthamoeba spp. 180 bp和H. vermiformis 502 bp),50 bp Plus DNA Ladder作为Marker,110 V电压条件下电泳30−40 min。

PCR扩增产物经测序确定为目的片段,纯化回收产物与pGEM-T Easy载体连接后导入大肠杆菌感受态细胞(DH5α),摇床培养后取适量转化液涂布于含有20 g/L 5-溴-4-氯-3-吲哚-β-D-半乳糖苷(X-Gal)、50 g/L异丙基-β-D-硫代吡喃半乳糖苷(IPTG)和100 g/L氨苄青霉素(Ampicillin)的LB平板进行蓝白斑筛选。挑取白色克隆菌落利用载体特异性引物T7和Sp6确定插入片段大小,经PCR鉴定为阳性的菌落转入含Amp (100 g/L)的LB液体培养基中,于37 °C条件下200 r/min摇床过夜培养。按照E.Z.N.A.® Plasmid Mini Kit I试剂盒说明书步骤提取质粒,NanoDrop 2000测定质粒DNA浓度。取1.5 mL培养菌液送测序公司(北京睿博兴科生物技术有限公司)对插入基因片段进行鉴定,测序结果通过NCBI的BLAST (http://www.ncbi.nih.gov/blast/)进行序列同源性检索比对。

1.3.3 定量标准品的制备及实时荧光定量PCR体系的建立: 根据已知浓度的重组质粒DNA和载体序列以及插入的18S rRNA基因序列片段大小,按以下公式计算标准品的拷贝数[23]:拷贝数=(质量/分子量)×6.02×1023。通过计算得出棘阿米巴属和哈曼属原虫18S rRNA基因每μl的绝对模板量分别为:6.51×109和7.18×109,将两种质粒模板按10倍稀释梯度稀释成标准曲线浓度。

定量PCR反应在Stratagene Mx3005P实时荧光定量PCR仪上进行。反应体系为20 μl:GoTaq qPCR Master Mix 10 μl,上下游引物(10 μmol/L)各0.4 μl,模板2 μl,加无菌ddH2O补齐至20 μl,反应于八联排管中进行。荧光定量PCR程序为:95 °C 2 min;94 °C 15 s,62 °C 30 s,72 °C 45 s,40个循环;72 °C 10 min。熔解曲线条件:95 °C 1 min,55 °C 30 s,95 °C 30 s,所有反应均设置3个重复,起始模板浓度由Ct值确定。每轮反应均以无菌ddH2O代替模板DNA作为阴性对照。

1.4 统计方法数据利用Excel 2007和IBM SPSS Statistics 20统计软件进行分析,组间比较采用One-way ANOVA,多重比较采用LSD检验。

2 结果与讨论 2.1 污水膜生物处理工艺各阶段水质参数膜-生物反应器工艺各阶段常规水质参数如表 1所示。由出水水质指标可见,该污水处理厂对农村生活污水的常规水质指标处理效果良好,COD和总氮平均去除率分别为89.9%和52.0%。与进水相比,出水中总磷含量略有升高,原因可能是由于工艺前段膜处理过程污泥释放出大量的磷素所造成。总氮和总磷的最大值出现在调节池,而好氧池和膜生物 反应池的各项指标均相对稳定。出水各项指标除总氮和总磷外均符合《城镇污水处理厂污染物排放标准》(GB 18918-2002)和《农田灌溉水质标准》(GB 5084-2005)。处理后的出水中微生物卫生指示菌细菌总数降低了3个数量级,大肠菌群和大肠杆菌均未检出。

| 指标 Parameters | 进水 Influent | 调节池 Adjusting tank | 好氧池 Aerobic tank | 膜池 Membrane tank | 出水 Effluent |

| pH | 7.60 | 7.31 | 7.37 | 7.44 | 7.59 |

| 电导率 Electrical conductivity (μs/cm) | 754 | 551 | 522 | 514 | 376 |

| 悬浮固体物 Suspended solid (mg/L) | 26 | 4 008 | 4 224 | 5 385 | 21 |

| 化学需用量 Chemical oxygen demand (mg/L) | 346 | 161 | 187 | 150 | 35 |

| 总氮 Total nitrogen (mg/L) | 54.6 | 226.0 | 72.6 | 85.2 | 26.2 |

| 总磷 Total phosphorus (mg/L) | 4.97 | 45.10 | 16.50 | 19.90 | 7.66 |

| 总大肠菌群 Total coliforms (CFU/mL) | 650 | 370 | 2 250 | 3 680 | − |

| 大肠杆菌 Escherichia coli (CFU/mL) | 1 890 | 630 | 400 | 510 | − |

| 细菌总数 Total bacteria (CFU/mL) | 1.24×106 | 3.34×106 | 1.65×105 | 2.60×105 | 2.80×103 |

通过水样的常规PCR产物的电泳图谱可以清晰显示目的基因片段(图 1),同时未观察到非特异性条带,说明样品中确实存在两类阿米巴原虫,并且实验所采用的PCR反应体系和条件均合适。

|

|

图 1

膜-生物处理工艺各阶段水样中原虫18S rRNA 基因(180 bp 和502 bp)的PCR 电泳图

Figure 1

Electrophoresis of 18S rRNA genes of Ameobae by PCR amplification

注:M:50 bp plus ladder;CK:阴性对照;1:进水;2:调节池;3:好氧池;4:膜池;5:出水.

Note: M: 50 bp plus ladder; CK: negative control; 1: Raw wastewater; 2: Adjusting tank; 3: Aerobic tank; 4: Membrane tank; 5: Treated wastewater. |

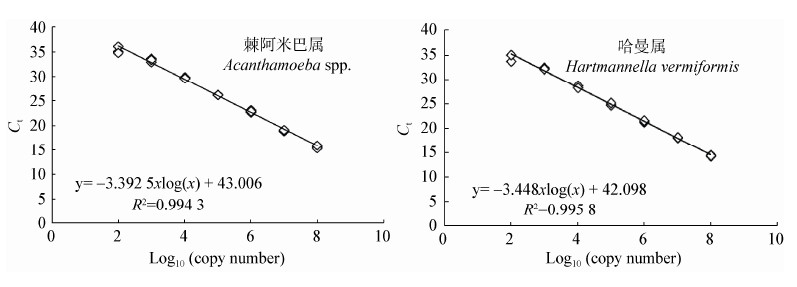

两类阿米巴原虫18S rRNA基因定量反应的标准曲线如图 2所示。由构建的质粒10倍梯度稀释所建立的标准曲线中,Ct值和log10基因拷贝数线性关系良好R2分别为0.994和0.996,斜率分别为−3.393和−3.448,扩增效率E分别为97.1%和95.0%。当模板浓度为101 copies/μL时,棘阿米巴虫和哈曼虫的Ct值分别为38.87和37.96,最低检出浓度分别为7.18×101 copies/μL和6.51×101 copies/μL。根据标准曲线计算出污水处理工艺不同阶段水样中的Ct值和基因拷贝数如图 3和表 2所示。

|

| 图 2 棘阿米巴原虫属和哈曼属原虫18S rRNA基因定量PCR的标准曲线 Figure 2 Standard curves for real-time PCR of 18S rRNA gene of Acanthamoeba spp. and Hartmannella vermiformis |

|

| 图 3 不同水样中棘阿米巴虫(A)和哈曼虫的绝对基因拷贝数(B) Figure 3 Acanthamoeba spp. (A) and Hartmannella vermiformis (B) absolute copy numbers in different wastewater samples Note: Different letters indicated significant differences (P<0.05). |

| 水样类型 Water type | 平均Ct值 Mean cycle threshold value (Ct) | 样品基因拷贝数 Gene copy numbers of samples (copies/L) | ||

| 棘阿米巴原虫属 Acanthamoeba spp. | 哈曼属原虫 Hartmannella vermiformis | 棘阿米巴原虫属 Acanthamoeba spp. | 哈曼属原虫 Hartmannella vermiformis | |

| 进水 Influent | 31.82±0.19 | 27.02±0.09 | 8.70×105 | 1.84×106 |

| 调节池 Adjusting tank | 35.89±0.22 | 34.66±0.95 | 6.31×104 | 2.49×104 |

| 好氧池 Aerobic tank | 35.97±0.10 | 32.65±0.16 | 5.94×104 | 1.28×105 |

| 膜池 Membrane tank | 34.93±0.07 | 35.09±0.91 | 1.16×105 | 1.58×104 |

| 出水 Effluent | 28.56±0.04 | 27.76±0.06 | 7.09×106 | 4.38×104 |

棘阿米巴原虫和哈曼属原虫在5个污水样品中的浓度范围分别为(5.94×104−7.09×106) copies/L和(1.58×104−1.84×106) copies/L,Ct值范围分别为28.56−35.97和27.02−35.09。棘阿米巴虫属和哈曼属原虫进入调节池、好氧池和膜池后,数量几乎下降至检出限。与之相比,出水中棘阿米巴虫属拷贝数比进水高出一个数量级,而哈曼属原虫的量降低了约两个数量级。

Muchesa等[24]利用最佳富集培养方法对南非豪登省一处污水处理厂厌氧生物反应器工艺流程中致病性阿米巴虫进行了检测。结果显示阿米巴虫在污水处理厂的8个处理阶段均被检出,而Acanthamoebasp.仅在夏秋季节检测到。研究中发现87.2%环境样品的阿米巴虫通过目前的污水处理工艺和氯消毒方法不能被有效地去除,因此未来的研究方向将结合培养和分子手段方法对人群易暴露的水体环境中的潜在致病性阿米巴虫进行检测。Marin等[25]对城市污水处理厂工艺流程中出现的细菌和寄生虫进行了描述,并探讨了净化的再生水和污泥在农业应用方面的可能性。在整个生物处理工艺过程中大肠杆菌得到有效去除,所有出水样品中均未检出Salmonellaspp.、Entamoeba、Cryptosporidium,Giardia duodenalis。通过分离培养和形态学鉴定,Acanthamoeba在污水和污泥中的检出频率最高。因此,利用处理后的出水进行农田灌溉可能会对健康产生潜在危害。Magnet等[14]利用平板培养和triplex real time PCR方法对不同水体中的Acanthamoeba、Balamuthia mandrillaris和Naegleria fowleri进行检测。Naegleria fowleri在所有样品中均未检出,而Balamuthia mandrillaris在自来水厂的进水中检测到。所有水样中观察到Acanthamoeba的出现率更高,结合分离培养和定量PCR方法得出的检出率高达99.1%,比较处理前后水样中的数量差异不显著。本文的研究结果与上述相关文献报道大体一致,在污水处理的各个工艺流程均检测到棘阿米巴虫和哈曼属原虫,但均未检出Naegleria fowleri,证实了这些阿米巴虫在自然水体中的普遍性。在整个工艺流程的各个反应池中,两类阿米巴原虫的数量基本保持稳定且含量较低,均在检出限附近。阿米巴虫作为一种侵袭神经系统的病原体由于其在环境中出现的频率高,因此需要引起足够重视。

值得注意的是,经过臭氧消毒后,棘阿米巴虫属原虫数量反而有所升高,可能是由于其自身孢囊的特殊结构保护抵抗不利的物理或生化环境,使其免受消毒剂的损害,同时也能够保护其胞内的病原菌。通过定量PCR方法有利于更好地了解阿米巴原虫在环境水体中的分布和丰度,该研究为农村生活污水处理厂中两类阿米巴虫的发生率提供了基准信息,对于污水受纳环境如地表水、地下水及农林耕地等中的致病性阿米巴虫及其他一些病原菌的传播具有重要的卫生学意义。

3 结论(1) 该污水处理厂所使用的膜-生物处理工艺对农村生活污水有良好的净化效果。稳定运行期间,出水的COD、SS、TN、TP及指示菌平均指标均符合《农田灌溉水质标准》(GB 5084-2005),而TN和TP略高于《城镇污水处理厂污染物排放标准》(GB 18918-2002)。

(2) 阿米巴原虫能够作为诸如军团菌、分枝杆菌和李斯特菌等病原菌的宿主,从而增强病原菌对消毒剂的抗性,促进病原菌的繁殖,甚至作为其传播的载体。因此,需要进一步考察阿米巴原虫与各类病原菌的共生关系,并连续监测主要水质参数与原虫发生率之间的相互关系。

(3) 本文证实了棘阿米巴属(Acanthamoeba spp.)和哈曼属原虫(Hartmannella vermiformis)在农村生活污水中普遍存在。今后我们需要考察不同污水处理工艺对原虫的去除效果,进一步分析致病性原虫的感染性,从而降低水体环境产生和传播病原体的健康风险。

| [1] | Li ZH, Li QX. Free-living amoeba is the media of many pathogenic bacteria and storage reservoir[J]. Chinese Journal of Epidemiology, 2006, 27(2): 174-178 李子华, 李勤学. 自由生活阿米巴是许多病原菌的传播媒 介和贮存宿主[J]. 中华流行病学杂志, 2006, 27(2): 174-178 |

| [2] | Tsvetkova N, Schild M, Panaiotov S, et al. The identification of free-living environmental isolates of amoebae from Bulgaria[J]. Parasitology Research, 2004, 92(5): 405-413 |

| [3] | Hsu BM, Lin CL, Shih FC. Survey of pathogenic free-living amoebae and Legionella spp. in mud spring recreation area[J]. Water Research, 2009, 43(11): 2817-2828 |

| [4] | Martinez AJ, Visvesvara GS. Free-living, amphizoic and opportunistic amebas[J]. Brain Pathology, 1997, 7(1): 583-598 |

| [5] | Marshall MM, Naumovitz D, Ortega Y, et al. Waterborne protozoan pathogens[J]. Clinical Microbiology Reviews, 1997, 10: 67-85 |

| [6] | Khan NA. Acanthamoeba: biology and increasing importance in human health[J]. FEMS Microbiology Reviews, 2006, 30(4): 564-595 |

| [7] | Centeno M, Rivera F, Cerva L, et al. Hartmannella vermiformis isolated from the cerebrospinal fluid of a young male patient with meningoencephalitis and bronchopneumonia[J]. Archives of Medical Research, 1996, 27(4): 579-586 |

| [8] | Szenasi Z, Endo T, Yagita K, et al. Isolation, identification and increasing importance of ‘free-living’ amoebae causing human disease[J]. Journal of Medical Microbiology, 1998, 47(1): 5-16 |

| [9] | Grimm D, Ludwig WF, Brandt BC, et al. Development of 18S rRNA-targeted oligonucleotide probes for specific detection of Hartmannella and Naegleria in Legionella-positive environmental samples[J]. Systematic and Applied Microbiology, 2001, 24(1): 76-82 |

| [10] | Stothard DR, Hay J, Schroeder-Diedrich JM, et al. Fluorescent oligonucleotide probes for clinical and environmental detection of Acanthamoeba and the T4 18S rRNA gene sequence type[J]. Journal of Clinical Microbiology, 1999, 37(8): 2687-2693 |

| [11] | Vodkin MH, Howe DK, Visvesvara GS, et al. Identification of Acanthamoeba at the generic and specific levels using the polymerase chain reaction[J]. The Journal of Protozoology, 1992, 39(3): 378-385 |

| [12] | Kao PM, Tung MC, Hsu BM, et al. Real-time PCR method for the detection and quantification of Acanthamoeba species in various types of water samples[J]. Parasitology Research, 2013, 112(3): 1131-1136 |

| [13] | Kuiper MW, Valster RM, Wullings BA, et al. Quantitative detection of the free-living amoeba Hartmannella vermiformis in surface water by using real-time PCR[J]. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 2006, 72(9): 5750-5756 |

| [14] | Magnet A, Fenoy S, Galvan AL, et al. A year long study of the presence of free living amoeba in Spain[J]. Water Research, 2013, 47(19): 6966-6972 |

| [15] | Scheid P, Schwarzenberger R. Acanthamoeba spp. as vehicle and reservoir of adenoviruses[J]. Parasitology Research, 2012, 111(1): 479-485 |

| [16] | Behets J, Declerck P, Delaedt Y, et al. Survey for the presence of specific free-living amoebae in cooling waters from Belgian power plants[J]. Parasitology Research, 2007, 100(6): 1249-1256 |

| [17] | Declerck P, Behets J, Van Hoef V, et al. Detection of Legionella spp. and some of their amoebae hosts in floating biofilms from anthropogenic and natural aquatic environments[J]. Water Research, 2007, 41(14): 3159-3167 |

| [18] | Chavatte N, Bare J, Lambrecht E, et al. Co-occurrence of free-living protozoa and foodborne pathogens on discloths: implications for food safety[J]. International Journal of Food Microbiology, 2014, 191: 89-96 |

| [19] | Pagnier I, Merchat M, La Scola B. Potentially pathogenic amoeba-associated microorganisms in cooling towers and their control[J]. Future Microbiology, 2009, 4(5): 615-629 |

| [20] | Thomas V, McDonnell G. Relationship between mycobacteria and amoebae: ecological and epidemiological concerns[J]. Letters in Applied Microbiology, 2007, 45(4): 349-357 |

| [21] | Huws SA, Morley RJ, Jones MV, et al. Interactions of some common pathogenic bacteria with Acanthamoeba polyphaga[J]. FEMS Microbiology Letters, 2008, 282(2): 258-265 |

| [22] | Qvarnstrom Y, Visvesvara GS, Sriram R, et al. Multiplex real-time PCR assay for simultaneous detection of Acanthamoeba spp., Balamuthia mandrillaris, and Naegleria fowleri[J]. Journal of Clinical Microbiology, 2006, 44(10): 3589-3595 |

| [23] | Smith CJ, Nedwell DB, Dong LF, et al. Evaluation of quantitative polymerase chain reaction based approaches for determining gene copy and gene transcript numbers in environmental samples[J]. Environmental Microbiology, 2006, 8(5): 804-815 |

| [24] | Muchesa P, Mwamba O, Barnard TG, et al. Detection of free-living amoebae using amoebal enrichment in a wastewater treatment plant of Gauteng Province, South Africa[J]. BioMed Research International, 2014: 1-10 |

| [25] | Marin I, Gorii P, Lasheras AM, et al. Efficiency of a Spanish wastewater treatment plant for removal potentially pathogens: characterization of bacteria and protozoa along water and sludge treatment lines[J]. Ecological Engineering, 2015, 74(1): 28-32 |

2015, Vol. 42

2015, Vol. 42