扩展功能

文章信息

- 于少兰, 乔延路, 韩彦琼, 张晓华

- YU Shao-Lan, QIAO Yan-Lu, AN Yan-Qiong, ZHANG Xiao-Hua

- 好氧氨氧化微生物系统发育及生理生态学差异

- Differencesbetween ammonia-oxidizing microorganisms in phylogeny and physiological ecology

- 微生物学通报, 2015, 42(12): 2457-2465

- Microbiology China, 2015, 42(12): 2457-2465

- 10.13344/j.microbiol.china.150115

-

文章历史

- 收稿日期: 2015-02-02

- 接受日期: 2015-04-09

- 优先数字出版日期(www.cnki.net): 2015-04-24

硝化作用是氮的生物地球化学循环的关键环节,包括好氧氨氧化和亚硝酸盐氧化两部分,分别由好氧氨氧化微生物和亚硝酸盐还原细菌介导。其中,好氧氨氧化作为硝化作用的主要限速步骤,受到广泛关注。在第一株氨氧化细菌(Ammonia-oxidizing bacteria,AOB)被成功分离后的一个多世纪里,AOB都被认为是唯一具有氨氧化能力的微生物,直到21世纪初,古菌氨单加氧酶α亚基基因(Ammonia monooxygenase α-subunit,amoA)的发现[1]以及氨氧化古菌Nitrosopumilus maritimus SCM1的分离培养[2],才使好氧氨氧化微生物从细菌域扩展到古菌域。氨氧化古菌(Ammonia-oxidizingarchaea,AOA)的发现,重新激起了人们对氨氧化微生物的研究热情。目前,在土壤、湖泊、河口、深海、污水处理池等多种环境中均发现了大量AOA和AOB的16S rRNA基因、amoA基因[3,4,5,6]。好氧氨氧化过程常与反硝化或厌氧氨氧化等过程耦合产生N2,起到氮移除的作用,对生态系统氮平衡、水体富营养化、土壤肥力等具有重要影响;另外,在废水处理生物脱氮工艺中,无论是传统的硝化-反硝化工艺还是新型的氨氧化-反硝化/厌氧氨氧化工艺,氨氧化都是其核心环节。因此,AOA和AOB的研究对环境保护、工农业生产等都具有重要意义。虽然好氧氨氧化微生物的生理学、生态学、基因组学、蛋白质组学等方面的研究使我们对它们有了一定了解,但由于研究方法的限制及其分布的复杂性和对环境胁迫的敏感性,目前仍无法确定AOA和AOB对全球氮循环的相对贡献,也尚不清楚如何调控它们的活性使其在生态修复、废水处理等方面发挥重要作用。其生理生态学差异将有助于我们进一步研究不同环境中AOA和AOB的群落组成和活性,但目前很少有文章将两者进行比较。本文将通过AOA和AOB的比较,从系统发育、对环境因子的响应、代谢途径等方面对氨氧化微生物相关研究成果进行概括和总结。

1 好氧氨氧化微生物系统发育虽然目前已培养的AOA和AOB种类较少,但克隆文库、高通量测序技术等为我们研究其系统发育提供了大量序列信息。16SrRNA基因是研究微生物进化关系及群落结构常用基因,在好氧氨氧化微生物中amoA基因与16S rRNA基因的系统发育树重合性较好,且相对于16SrRNA基因,amoA基因表现出更高的差异性,可以更好地区别16SrRNA基因相似性较高的不同种。因此,amoA作为分子标记广泛应用于环境氨氧化微生物群落结构研究中。

1.1 氨氧化古菌2008年,科学家们通过系统发生学和酶学分析,将包括氨氧化古菌在内的部分泉古菌类群重新划分成一个新门——奇古菌门[7]。根据16S rRNA和amoA基因的系统发育分析,目前已知的AOA划分为group I.1a、group I.1b、ThAOA和group I.1a-associated四个类群。N. maritimus SMC1是第一株分离培养的氨氧化古菌[2],属于group I.1a类群,它的发现使古菌的氨氧化功能得到证实,是好氧氨氧化微生物研究的重要里程碑。之后,人们又成功地从贫瘠土壤、淡水沉积物、农田等多种环境中富集了group I.1a菌株[8,9,10]。最近,从地热温泉中富集的Nitrosotenuis uzonensis扩大了我们对这类AOA分布的认识[11]。2008年,第一株group I.1b氨氧化古菌Nitrososphaera gargensis从热泉微生物席中被分离培养[12]。随后又有多株group I.1b中的AOA被富集或分离,其中Nitrososphaera viennensis EN76是第一株从土壤环境中分离培养的AOA,它的纯培养为在土壤环境中广布的group I.1b类群古菌的研究提供了模式生物,是中温古菌研究的又一里程碑[13]。Nitrosocaldus yellowstonii则代表了在高温环境中广泛存在的一个分支——嗜热AOA类群ThAOA[14]。2011年富集到的Nitrosotalea devanaterra是目前唯一的专性嗜酸氨氧化微生物,隶属于group I.1a-associated类群[15]。酸性土壤约占无冰陆地表面30%,并且其中的硝化反应速率较高,是研究全球氮循环不可缺少的一环,所以这个发现为进一步研究氮的生物地球化学循环提供了重要条件。

除了上述已分离或富集培养的AOA之外,基于amoA基因克隆文库的分析表明,自然环境中还存在大量未知AOA。2012年Pester等将从NCBI、IMG/M以及Camera 3个数据库中获得的所有古菌amoA序列用距离矩阵法、最大简约法和最大似然法3种方法建树,划分为5个簇[16],其中Nitrosopumilis、Nitrososphaera、Nitrosocaldus、Nitrosotalea cluster分别对应已知AOA分类中的group I.1a、group I.1b、ThAOA和group I.1a-associated类群,而Nitrososphaera sister cluster类群中还未有AOA被描述。Nitrosopumilis cluster在海洋水体和沉积物AOA中占主导地位,而Nitrososphaera cluster则主要存在于土壤以及潮间带、河口等低盐环境中。

1.2 氨氧化细菌目前为止,已知的AOB均属于β-变形菌纲的亚硝化单胞菌属(Nitrosomonas)、亚硝化螺菌属(Nitrosospira)和γ-变形菌纲的亚硝化球菌属(Nitrosococcus)。Purkhold等根据16S rRNA基因的系统发育树将β-变形菌纲中的AOB分为10个簇[17]。Avrahami等根据amoA基因系统发育树将β-变形菌纲中的AOB分为12个簇[18],其簇与16S rRNA基因系统发育树中的相对应,并新增加了Nitrosospira cluster 9−12。2010年Dang等又在此基础上新划分出3个簇Nitrosospira cluster 13−15[19]。其中,Nitrosospira cluster 2、3、4、10、11、12及Nitrosomonas cluster 7是土壤中主要的氨氧化细菌类群,土壤酸度及氨浓度是影响其分布模式的主要环境因子[20,21]。Nitrosomonas cluster 6a则是淡水生态系统、废水以及生物滤池中的主要类群,在河口和近岸等受淡水、废水影响较大的低盐环境中也有发现[3,17]。海洋环境中存在大量Cluster 13−15氨氧化细菌类群:Cluster 13主要分布在近岸海洋环境中;Cluster 14在近岸和深海的高盐度环境均有发现;而Cluster 15则主要存在于近岸和河口,特别在河口环境中尤为常见[3,19]。由于缺少相应已培养的AOB,Cluster9−15在16S rRNA基因进化树上还无法找到与其对应的分支,需要通过更多的纯培养AOB和克隆序列来进一步确定。

在已纯培养的AOB中,Nitrosomonas europaea作为研究好氧氨氧化微生物生理、生化和系统发育等方面的模式生物之一[22,23,24],是目前研究最多的氨氧化微生物。Nitrosococcus oceani是γ-变形菌纲中唯一在海洋环境中广泛存在的种[25]。2014年,Urakawa等又定义了一个新种Nitrosospira lacus,其标准菌株APG3分离自淡水湖沉积物,是一株耐寒、广pH的陆源氨氧化细菌[26]。这种具有独特生境选择的AOB为自然界中氨氧化微生物的微生物生态学研究提供了新的认知。

2 对环境因子的响应AOA和AOB的群落结构、丰度和活性在不同环境中具有差异性,根本原因在于二者对环境因子的响应不同。

2.1 氨控制好氧氨氧化微生物分布的主要因素之一是底物(NH4+/NH3)浓度。对于培养的AOA和AOB的动力学研究表明,大部分AOB的半饱和常数Km值较高(>20 μmol/L),只有少数的几株对底物浓度要求较低,如Nitrosomonas ureae和Nitrosomonas oligotropha[27]。而AOA的Km值(<1 μmol/L)和可耐受氨的最大浓度普遍较低[28],尤其是Group I.1a中的N. maritimus SCM1底物的半饱和常数极低(Km=133 nmol/L),且其可耐受的氨的最高浓度不超过1 mmol/L[29]。另外,在AOA占主导地位的普吉特海湾和马尾藻海水体中,氨氧化微生物的Km值也极低(<100 nmol/L)[30,31],表明在海洋原位环境中

AOA对氨也具有极高的亲和力。对不同环境样品和培养物中AOA和AOB的活性及丰度的检测结果同样证明了AOA比AOB更适合寡营养环境:在淡水沉积物的AOA和AOB富集培养物中,NH3的增加可以提高AOB的生长速率,而对于AOA的生长速率则有所抑制[9];土壤环境样品中,AOB只在NH4+-N浓度较高(200 μg/g)的条件下才能生长,而AOA在NH4+-N浓度<0.5μg/g的条件下仍可生长[5],且在含氮量高的草原土壤中,AOB的丰度和活性随NH4+-N浓度升高而增加,并与硝化活性呈正相关[32];在寡营养的开放性海域,AOA的丰度高于AOB并且与硝化速率有很高的相关性[33,34];而在富营养的污水处理厂活性污泥里,AOB的活性和丰度更高[6]。因此AOB可能在富营养化的水体、施肥土壤、污水处理池等NH4+浓度较高的环境下的氨氧化过程中发挥重要作用,而AOA则是寡营养环境下氨氧化作用的主要执行者。氨的浓度对AOA和AOB群落结构也有影响,在北极沿海和大西洋热带海区上层水体中主要的AOA类群为适中氨类群HAC-AOA,而在氨浓度极低的大西洋热带海区中、下层水体中适低氨类群LAC-AOA占有优势[35];对象山湾AOB群落结构研究表明,污染程度不同的近岸站和远岸站的AOB群落分别聚集成簇,其分布模式与NH4+-N浓度显著相关[36],同样的结果在长江口潮间带也被报道[37]。

2.2 温度温度是影响氨氧化微生物分布模式的重要环境因素之一:在土壤、湖泊、海洋等中温环境中包括Nitrosoarchaeum limnia、N. koreenisis、N. maritimus等在内的适中温类群占主导地位,而包括N. yellowstonii和N. gargensis等在内的嗜热类群则是热泉环境中常见类群。同样,温度对AOB群落结构也有重要影响,例如:在珠江口到南海的深海站位与浅海站位沉积物AOB群落结构存在明显差异,温度是造成这种差异的主要原因之一[3];在北美森林、荒漠、草地等土壤中,温度的年度差异与AOB群落结构变化密切相关[38]。以往研究表明,AOA对高温环境的适应性高于AOB:已培养的N. yellowstonii的最适温度高达72 °C,在60−74 °C下具有较高的亚硝酸盐产生速率[14],甚至在温度高达97 °C的热泉环境中仍可检测到N. yellowstonii和N. gargensis相关类群古菌的amoA相关基因及其转录产物。热泉环境中氨氧化是产能最多的生理过程之一,AOA在此过程中起着至关重要的作用[39]。而已培养的AOB的最适温度一般在20−30 °C,且目前为止还未在恒温高于40 °C的环境中检测到AOB的相关基因。温度不但影响着AOA和AOB的群落结构和活性,且对其多样性水平也有影响:对中国海域沉积物中氨氧化微生物研究结果表明AOA的多样性在位于热带的南海地区相对较高,而AOB的多样性则在位于温带的黄、渤海区较高[3,19,34]。

2.3 溶氧在很多AOA占主导地位的环境中,溶氧量(Dissolved oxygen,DO)都较低。在南太平洋东部的热带少氧海区水体及低氧的阿拉伯海水体中AOA的丰度均较高,且高于DO值较高的表层水体[40]。在珠江口DO值<1mg/L的水体中,AOA占主导地位的Marine group I类群的相对丰度明显高于DO值>5 mg/L的水体[41]。虽然AOA对低氧环境有很强的偏好性和适应性,但是好氧氨氧化是一个严格需氧的过程,氧气的可利用性对于AOA的分布和活性有重要影响。在阿拉伯海DO浓度约为5 μmol/L的上层低氧水体中AOA的丰度和活性较高,而在600−750 m氧气浓度低于检测极限时,AOA的丰度及amoA基因的转录产物也最少,说明此时氧气的浓度已不足以支持AOA的氨氧化作用[42]。与AOA相比,AOB对环境DO量要求较高:Abell等发现在不同溶氧处理的沉积样品中,细菌amoA基因的转录量随着DO浓度的降低而减少,且不同DO条件下的转录的细菌amoA类型也不同,但是古菌amoA的转录量和转录类群在不同溶氧样品间没有明显变化[43];在旱地土壤中,深层缺氧土层AOA的丰度较表层无明显变化,而AOB的丰度则急剧降低[44],类似结果在湿地土壤、湖泊沉积物等样品中也有报道[45,46]。另外,在含氧量较低(<10 μmol/L)的水体中AOA的丰度明显高于AOB[47]。对富集或纯培养的氨氧化微生物的动力学研究表明AOA的氨单加氧酶(Ammonia monooxygenase,AMO)展现出更高的氧气亲和力[48,49]。综上所述,AOA对低氧环境的适应性更强,在低氧的海水、土壤、沉积物等环境中对硝化作用的贡献可能大于AOB。

2.4 pH在酸性红土中AOB的Nitrosospira类群中的cluster 10、11和12占有优势,而Nitrosospira的cluster 3a.1、3a.2及Nitrosomonas的cluster 6和7主要存在于碱性和中性土壤中[21]。AOA中的group 1.1a的丰度与土壤pH值成反比,而group 1.1b的丰度与pH值成正比[21]。尽管不同分支间pH的偏好存在差异,但从总体水平上来说AOA对酸性环境的适应性高于AOB。虽然目前为止只培养出一株专性嗜酸AOA,但是Nitrososphaera cluster和其他amoA分支在酸性土壤中的广泛存在表明还有其他适应低pH的AOA[16,50],而AOB在低pH的环境中丰度和活性很低甚至为零[51]。贾仲君课题组发现,在酸性土壤中Nitrososphaera clusters的AOA是氨氧化过程的主要参与者[52,53]。另外,贺纪正课题组研究表明,在不同pH土壤中,AOA和AOB群落对环境变化的响应不同:在酸性红土中,长期施肥会引起AOA群落结构显著变化[54];而在同样长期施肥的碱性土壤中AOB的群落组成变化显著[55]。在酸性土壤环境中潜在硝化速率与AOA的丰度显著相关而与AOB丰度无关[56,57],而在碱性土壤中的研究结果恰好相反[55]。以上研究表明,AOA可能在酸性土壤中的氨氧化过程中发挥主要作用,而AOB则是碱性土壤中对氨氧化起主导作用的微生物。另外,在pH较低的黄海及渤海表层沉积物中,AOA占主导地位的Marine group I类群在古菌中的相对丰度高于pH较高的东海北部沉积[58];在珠江口水体中,其相对丰度在pH较低的上游高于pH较高的下游地区,表明AOA可能较其他古菌更能适应较低pH[41]。说明在营养较丰富的边缘海,低pH沉积物中AOA对氨氧化作用的贡献可能较高pH区更突出。

此外,光照、盐度、金属离子等因素也对氨氧化微生物的分布有一定的影响。

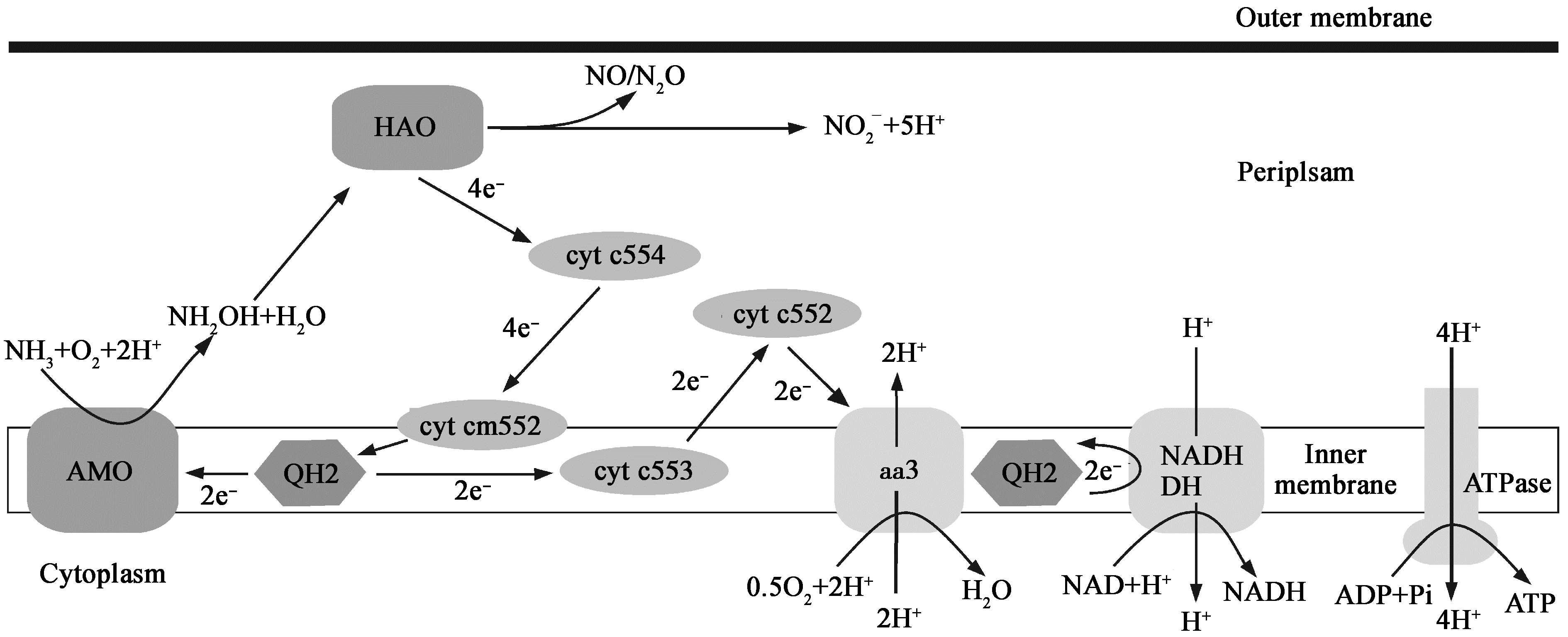

3 代谢途径 3.1 氨氧化在AOB中,AMO催化氨的好氧氧化生成羟胺,羟胺被周质的羟胺氧化还原酶(Hydroxylamineoxidoreductase,HAO)氧化成亚硝酸盐。具体反应如下:(1)2H++NH3+2e−+O2→NH2OH+H2O;(2) NH2OH+H2O→NO2−+4e−+5H+。其中第二步生成的电子中有两个电子用来补偿第一步反应,剩下的两个电子经过电子传递链传递到末端氧化酶从而形成质子动力势;(3)2H++1/2O2+2e−→H2O (图 1)。对于古菌N. maritimus的氨氧化作用化学计量学分析表明其产生亚硝酸根所需的氧气和氨的相对量与AOB的相似,它们总反应式为NH3+1.5O2→NO2−+H++H2O[29]。Vajrala等通过稳定同位素示踪法发现N. maritimus的氨氧化过程中有NH2OH的产生和消耗并且伴随着能量的产生,证明羟胺是其氨氧化过程的中间产物,AOA中的氨氧化过程可能与AOB相似[59],但是目前AOA的具体氨氧化过程尚未探明。在已知的AOA的基因组中还没有发现类似于AOB中的羟胺氧化还原酶基因hao,可能在AOA中存在未知的酶可代替HAO氧化羟胺。另外,也有观点认为古菌的AMO或其他酶催化反应可能产生HNO,HNO被硝酰氧化还原酶(Nitroxyloxidoreductase,NxOR)氧化生成NO2−[60]。而且与AOB相比,AOA中没有细胞色素c基因而是存在大量编码多铜氧化酶和质体蓝素域蛋白的基因,这表明AOA的电子传递机制与AOB不同[60,61]。

|

|

图 1

AOB中氨氧化过程及其电子传递途径(基于[27])

Figure 1

Pathway for ammonia oxidation and the electron transport chain in AOB (modified from [27])

注:AMO:氨单加氧酶;HAO:羟胺氧化还原酶;cyt c:细胞色素C;aa3:细胞色素氧化酶aa3;QH2:还原型辅酶Q;NADHDH:NADH脱氢酶;ATPase:ATP合成酶. Note: AMO: Ammoniamonoxygenase; HAO: Hydroxylamine oxidoreductase; cyt c: Cytochrom c; aa3:Cytochrome oxidase aa3; QH2: Reduced coenzyme Q; NADH DH: NADH dehydrogenase;ATPase: ATP synthase. |

通常认为氨氧化微生物是能利用氨作为唯一能源、以CO2作为主要碳源的化能自养微生物,但是AOA和AOB在固碳方面存在重要差异。AOB通过卡尔文循环固碳,每固定1分子的CO2需消耗3分子的ATP和2分子的NADPH,据估计其产生的能量80%用来固碳[62]。而AOA基因组中包含乙酰辅酶A/丙酰辅酶A羧化酶、甲基丙二酰辅酶A差向异构酶和变位酶、4-羟基丁酸脱氢酶等酶的编码基因,通过3-羟基丙酸/4-羟基丁酸(3-hydroxypropionate/4-hydroxybutyrate,3HP/4HB)途径固碳[60,63]。研究表明,AOA固定CO2的方式最节能,固定等量CO2所消耗的能量是AOB的2/3,比拥有相似固碳途径的泉古菌消耗的能量还要低,这为它们在寡营养环境中生存提供了条件[64]。不同的固碳途径对氨氧化微生物生态适应性有重要影响:3HP/4HB途径中固定的是HCO3−,而HCO3−是海洋环境中主要的碳素存在形式,这为AOA在海洋中的广泛分布提供了条件;而卡尔文循环固定的是CO2,且在AOB的基因组中有碳酸酐酶编码基因[65],可以将HCO3−转化成CO2,因此AOB利用的无机碳源范围更广。

3.3 产N2O研究表明AOA和AOB都能产生N2O。在AOB中主要通过2种途径生成N2O:在有氧条件下,羟胺在HAO的作用下氧化成NO,进而形成N2O[66];在低氧条件下,AOB主要通过硝化菌反硝化作用在亚硝酸盐还原酶的作用下将亚硝酸还原成NO,再经一氧化氮还原酶(Nitricoxide reductase,NOR)还原成N2O[67]。与AOB不同,目前对于AOA产生N2O的代谢过程仍然存在争议,因为在AOA的基因组中既缺少类似于AOB中的hao基因,又缺少参与硝化菌反硝化作用的nor基因。Löscher等研究表明AOA可通过未知的中间产物在氨氧化过程中产生N2O[68]。Jung等通过同位素示踪证明土壤AOA富集物产生的N2O存在15,15N2O、14,15N2O、14,14N2O3种形式,它们可能分别由氨氧化、硝化菌反硝化作用及两个代谢途径结合产生[69]。而纯培养的N. viennensis可能通过混合形成机制产生N2O,在这个过程中来源于亚硝酸的N原子与来源于氨或者氨氧化作用中间产物的N原子通过酶学反应结合生成N2O[70]。具体过程如图 2所示[71]。

基于16S rRNA和amoA基因的研究揭示了好氧氨氧化微生物的群落结构特征,而同位素示踪技术及全基因组测序技术的应用使我们对好氧氨氧化微生物生态作用机理有了更多了解。但是,目前仍然存在很多需要努力的方面,如:(1)探求AOA的具体氨氧化途径,特别是明确催化羟胺氧化的酶及其相关基因;(2)AOB与亚硝化细菌间相互依存的关系是两种功能微生物代谢耦合的典型范例,但AOA和亚硝酸盐氧化细菌之间的关系尚不清楚;(3) 尽管分子生物学研究表明自然环境中AOA和AOB的多样性极高,但纯培养的种类却极少,严重影响了氨氧化微生物生理生态学研究。单细胞测序技术使获得环境样品中未分离培养的微生物全基因组信息成为可能;宏基因组和宏转录组测序技术可以从环境样品中获得大量序列信息,结合蛋白质学研究能更好地推断氨氧化微生物的功能和环境适应性;两者在环境氨氧化微生物中应用将从一定程度上减轻培养困难对功能研究造成的困扰。另外,高分辨率的二次离子质谱分析技术为原位研究好氧氨氧化微生物代谢途径提供了有效手段。用微包埋培养取代传统培养方法[72],将为氨氧化微生物培养提供更有利的条件。

| [1] | Venter JC, Remington K, Heidelberg JF, et al. Environmental genome shotgun sequencing of the Sargasso Sea[J].Science, 2004, 304(5667): 66-74 |

| [2] | K?nneke M, Bernhard AE, de la Torre JR, et al. Isolation of an autotrophic ammonia-oxidizing marine archaeon[J].Nature, 2005, 437(7058): 543-546 |

| [3] | Cao HL, Hong YG, Li M, et al. Community shift of ammonia-oxidizing bacteria along an anthropogenic pollution gradient from the Pearl River Delta to the South China Sea[J].Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology, 2012, 94(1): 247-259 |

| [4] | Hou J, Song CL, Cao XY, et al. Shifts between ammonia-oxidizing bacteria and archaea in relation to nitrification potential across trophic gradients in two large Chinese lakes (Lake Taihu and Lake Chaohu)[J].Water Research, 2013, 47(7): 2285-2296 |

| [5] | Verhamme DT, Prosser JI, Nicol GW. Ammonia concentration determines differential growth of ammonia-oxidising archaea and bacteria in soil microcosms[J].The ISME Journal, 2011, 5(6): 1067-1071 |

| [6] | Jin T, Zhang T, Yan QM. Characterization and quantification of ammonia-oxidizing archaea (AOA) and bacteria (AOB) in a nitrogen-removing reactor using T-RFLP and qPCR[J].Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology, 2010, 87(3): 1167-1176 |

| [7] | Brochier-Armanet C, Boussau B, Gribaldo S, et al. Mesophilic crenarchaeota: proposal for a third archaeal phylum, the Thaumarchaeota[J].Nature Reviews Microbiology, 2008, 6(3): 245-252 |

| [8] | Jung MY, Park SJ, Min D, et al. Enrichment and characterization of an autotrophic ammonia-oxidizing archaeon of mesophilic Crenarchaeal Group I. 1α from an agricultural soil[J].Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 2011, 77(24): 8635-8647 |

| [9] | French E, Kozlowski JA, Mukherjee M, et al. Ecophysiological characterization of ammonia-oxidizing archaea and bacteria from freshwater[J].Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 2012, 78(16): 5773-5780 |

| [10] | Jung MY, Park SJ, Kim SJ, et al. A mesophilic, autotrophic, ammonia-oxidizing archaeon of Thaumarchaeal group I. 1α cultivated from a deep oligotrophic soil horizon[J].Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 2014, 80(12): 3645-3655 |

| [11] | Lebedeva EV, Hatzenpichler R, Pelletier E, et al. Enrichment and genome sequence of the group I. 1α ammonia-oxidizing Archaeon “Ca. Nitrosotenuis uzonensis” representing a clade globally distributed in thermal habitats[J].PLoS One, 2013, 8(11): e80835 |

| [12] | Hatzenpichler R, Lebedeva EV, Spieck E, et al. A moderately thermophilic ammonia-oxidizing crenarchaeote from a hot spring[J].Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 2008, 105(6): 2134-2139 |

| [13] | Stieglmeier M, Klingl A, Alves RJ, et al. Nitrososphaera viennensis gen. nov., sp. nov., an aerobic and mesophilic, ammonia-oxidizing archaeon from soil and a member of the archaeal phylum Thaumarchaeota[J].International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology, 2014, 64(Pt8): 2738-2752 |

| [14] | de la Torre JR, Walker CB, Ingalls AE, et al. Cultivation of a thermophilic ammonia oxidizing archaeon synthesizing crenarchaeol[J].Environmental Microbiology, 2008, 10(3): 810-818 |

| [15] | Lehtovirta-Morley LE, Stoecker K, Vilcinskas A, et al. Cultivation of an obligate acidophilic ammonia oxidizer from a nitrifying acid soil[J].Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 2011, 108(38): 15892-15897 |

| [16] | Pester M, Rattei T, Flechl S, et al. amoA-based consensus phylogeny of ammonia-oxidizing archaea and deep sequencing of amoA genes from soils of four different geographic regions[J].Environmental Microbiology, 2012, 14(2): 525-539 |

| [17] | Purkhold U, Wagner M, Timmermann G, et al. 16S rRNA and amoA-based phylogeny of 12 novel betaproteobacterial ammonia-oxidizing isolates: extension of the dataset and proposal of a new lineage within the nitrosomonads[J].International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology, 2003, 53(5): 1485-1494 |

| [18] | Avrahami S, Conrad R. Patterns of community change among ammonia oxidizers in meadow soils upon long-term incubation at different temperatures[J].Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 2003, 69(10): 6152-6164 |

| [19] | Dang HY, Li J, Chen RP, et al. Diversity, abundance, and spatial distribution of sediment ammonia-oxidizing Betaproteobacteria in response to environmental gradients and coastal eutrophication in Jiaozhou Bay, China[J].Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 2010, 76(14): 4691-4702 |

| [20] | Yao HY, Campbell CD, Chapman SJ, et al. Multi-factorial drivers of ammonia oxidizer communities: evidence from a national soil survey[J].Environmental Microbiology, 2013, 15(9): 2545-2556 |

| [21] | Shen JP, Zhang LM, Di HJ, et al. A review of ammonia-oxidizing bacteria and archaea in Chinese soils[J].Frontiers in Microbiology, 2012, 3: 296 |

| [22] | Kozlowski JA, Price J, Stein LY. Revision of N2O-producing pathways in the ammonia-oxidizing bacterium Nitrosomonas europaea ATCC 19718[J].Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 2014, 80(16): 4930-4935 |

| [23] | Mehrotra PV, Brunson K, Hooper A, et al. Expression of two Nitrosomonas europaea proteins, hydroxylamine oxidoreductase and Ne0961, in Escherichia coli[J].Proceedings of the South Dakota Academy of Science, 2012, 91: 145-157 |

| [24] | Dong NM, Risgaard-Petersen N, S?rensen J, et al. Rapid and sensitive Nitrosomonas europaea biosensor assay for quantification of bioavailable ammonium sensu strictu in soil[J].Environmental Science and Technology, 2011, 45(3): 1048-1054 |

| [25] | Ward BB, O’mullan GD. Worldwide distribution of Nitrosococcus oceani, a marine ammonia-oxidizing γ-proteobacterium, detected by PCR and sequencing of 16S rRNA and amoA genes[J].Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 2002, 68(8): 4153-4157 |

| [26] | Urakawa H, Garcia JC, Nielsen JL, et al. Nitrosospira lacus sp. nov., a psychrotolerant, ammonia-oxidizing bacterium from sandy lake sediment[J].International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology, 2015, 65(Pt1): 242-250 |

| [27] | Guo JH, Peng YZ, Wang SY, et al. Pathways and organisms involved in ammonia oxidation and nitrous oxide emission[J].Critical Reviews in Environmental Science and Technology, 2013, 43(21): 2213-2296 |

| [28] | Hatzenpichler R. Diversity, physiology, and niche differentiation of ammonia-oxidizing archaea[J].Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 2012, 78(21): 7501-7510 |

| [29] | Martens-Habbena W, Berube PM, Urakawa H, et al. Ammonia oxidation kinetics determine niche separation of nitrifying Archaea and Bacteria[J].Nature, 2009, 461(7266): 976-979 |

| [30] | Horak REA, Qin W, Schauer AJ, et al. Ammonia oxidation kinetics and temperature sensitivity of a natural marine community dominated by archaea[J].The ISME Journal, 2013, 7(10): 2023-2033 |

| [31] | Newell SE, Fawcett SE, Ward BB. Depth distribution of ammonia oxidation rates and ammonia-oxidizer community composition in the Sargasso Sea[J].Limnology and Oceanography, 2013, 58(4): 1491-1500 |

| [32] | Di HJ, Cameron KC, Shen JP, et al. Nitrification driven by bacteria and not archaea in nitrogen-rich grassland soils[J].Nature Geoscience, 2009, 2(9): 621-624 |

| [33] | Beman JM, Popp BN, Francis CA. Molecular and biogeochemical evidence for ammonia oxidation by marine Crenarchaeota in the Gulf of California[J].The ISME Journal, 2008, 2(4): 429-441 |

| [34] | Dang HY, Zhou HX, Yang JY, et al. Thaumarchaeotal signature gene distribution in sediments of the northern South China Sea: an indicator of the metabolic intersection of the marine carbon, nitrogen, and phosphorus cycles?[J].Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 2013, 79(7): 2137-2147 |

| [35] | Sintes E, Bergauer K, de Corte D, et al. Archaeal amoA gene diversity points to distinct biogeography of ammonia-oxidizing Crenarchaeota in the ocean[J].Environment Microbiology, 2013, 15(5): 1647-1658 |

| [36] | Hou MH, Xiong JB, Wang K, et al. Communities of sediment ammonia-oxidizing bacteria along a coastal pollution gradient in the East China Sea[J].Marine Pollution Bulletin, 2014, 86(1/2): 147-153 |

| [37] | Zheng YL, Hou LJ, Newell S, et al. Community dynamics and activity of ammonia-oxidizing prokaryotes in intertidal sediments of the Yangtze Estuary[J].Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 2014, 80(1): 408-419 |

| [38] | Fierer N, Carney KM, Horner-Devine MC, et al. The biogeography of ammonia-oxidizing bacterial communities in soil[J].Microbial Ecology, 2009, 58(2): 435-445 |

| [39] | Dodsworth JA, Hungate BA, Hedlund BP. Ammonia oxidation, denitrification and dissimilatory nitrate reduction to ammonium in two US Great Basin hot springs with abundant ammonia-oxidizing archaea[J].Environmental Microbiology, 2011, 13(8): 2371-2386 |

| [40] | Peng X, Jayakumar A, Ward BB. Community composition of ammonia-oxidizing archaea from surface and anoxic depths of oceanic oxygen minimum zones[J].Frontiers in Microbiology, 2013, 4: 177 |

| [41] | Liu JW, Yu SL, Zhao MX, et al. Shifts in archaeaplankton community structure along ecological gradients of Pearl Estuary[J].FEMS Microbiology Ecology, 2014, 90(2): 424-435 |

| [42] | Han MQ, Li ZY, Zhang FL. The ammonia oxidizing and denitrifying prokaryotes associated with sponges from different sea areas[J].Microbial Ecology, 2013, 66(2): 427-436 |

| [43] | Abell GCJ, Banks J, Ross DJ, et al. Effects of estuarine sediment hypoxia on nitrogen fluxes and ammonia oxidizer gene transcription[J].FEMS Microbiology Ecology, 2011, 75(1): 111-122 |

| [44] | Leininger S, Urich T, Schloter M, et al. Archaea predominate among ammonia-oxidizing prokaryotes in soils[J].Nature, 2006, 442(7104): 806-809 |

| [45] | Wang Y, Zhu GB, Ye L, et al. Spatial distribution of archaeal and bacterial ammonia oxidizers in the littoral buffer zone of a nitrogen-rich lake[J].Journal of Environmental Sciences, 2012, 24(5): 790-799 |

| [46] | Zhao DY, Zeng J, Wan WH, et al. Vertical distribution of ammonia-oxidizing archaea and bacteria in sediments of a Eutrophic Lake[J].Current Microbiology, 2013, 67(3): 327-332 |

| [47] | Molina V, Belmar L, Ulloa O. High diversity of ammonia-oxidizing archaea in permanent and seasonal oxygen-deficient waters of the eastern South Pacific[J].Environmental Microbiology, 2010, 12(9): 2450-2465 |

| [48] | Park BJ, Park SJ, Yoon DN, et al. Cultivation of autotrophic ammonia-oxidizing archaea from marine sediments in coculture with sulfur-oxidizing bacteria[J].Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 2010, 76(22): 7575-7587 |

| [49] | Martens-Habbena W, Stahl DA. Nitrogen metabolism and kinetics of ammonia-oxidizing archaea[J].Methods in Enzymology, 2011, 496: 465-487 |

| [50] | Gubry-Rangin C, Hai B, Quince C, et al. Niche specialization of terrestrial archaeal ammonia oxidizers[J].Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 2011, 108(52): 21206-21211 |

| [51] | Schmidt CS, Hultman KA, Robinson D, et al. PCR profiling of ammonia-oxidizer communities in acidic soils subjected to nitrogen and sulphur deposition[J].FEMS Microbiology Ecology, 2007, 61(2): 305-316 |

| [52] | Huang R, Wu YC, Zhang JB, et al. Nitrification activity and putative ammonia-oxidizing archaea in acidic red soils[J].Journal of Soils and Sediments, 2012, 12(3): 420-428 |

| [53] | Wang BZ, Zheng Y, Huang R, et al. Active ammonia oxidizers in an acidic soil are phylogenetically closely related to neutrophilic archaeon[J].Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 2014, 80(5): 1684-1691 |

| [54] | He JZ, Shen JP, Zhang LM, et al. Quantitative analyses of the abundance and composition of ammonia-oxidizing bacteria and ammonia-oxidizing archaea of a Chinese upland red soil under long-term fertilization practices[J].Environmental Microbiology, 2007, 9(9): 2364-2374 |

| [55] | Shen JP, Zhang LM, Zhu YG, et al. Abundance and composition of ammonia-oxidizing bacteria and ammonia-oxidizing archaea communities of an alkaline sandy loam[J].Environmental Microbiology, 2008, 10(6): 1601-1611 |

| [56] | Gubry-Rangin C, Nicol GW, Prosser JI. Archaea rather than bacteria control nitrification in two agricultural acidic soils[J].FEMS Microbiology Ecology, 2010, 74(3): 566-574 |

| [57] | Zhang LM, Hu HW, Shen JP, et al. Ammonia-oxidizing archaea have more important role than ammonia-oxidizing bacteria in ammonia oxidation of strongly acidic soils[J].The ISME Journal, 2012, 6(5): 1032-1045 |

| [58] | Liu JW, Liu XS, Wang M, et al. Bacterial and archaeal communities in sediments of the North Chinese Marginal Seas[J].Microbial Ecology, 2015, 70(1): 105-117 |

| [59] | Vajrala N, Martens-Habbena W, Sayavedra-Soto LA, et al. Hydroxylamine as an intermediate in ammonia oxidation by globally abundant marine archaea[J].Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 2013, 110(3): 1006-1011 |

| [60] | Walker CB, de la Torre JR, Klotz MG, et al. Nitrosopumilus maritimus genome reveals unique mechanisms for nitrification and autotrophy in globally distributed marine crenarchaea[J].Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 2010, 107(19): 8818-8823 |

| [61] | Blainey PC, Mosier AC, Potanina A, et al. Genome of a low-salinity ammonia-oxidizing archaeon determined by single-cell and metagenomic analysis[J].PLoS One, 2011, 6(2): e16626 |

| [62] | Pérez J. Transcriptome profiling of Nitrosomonas europaea grown singly and in co-culture with Nitrobacter winogradskyi[D].Corvallis: Master’s Thesis of Oregon State University, 2014 |

| [63] | Tourna M, Stieglmeier M, Spang A, et al. Nitrososphaera viennensis, an ammonia oxidizing archaeon from soil[J].Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 2011, 108(20): 8420-8425 |

| [64] | K?nneke M, Schubert DM, Brown PC, et al. Ammonia-oxidizing archaea use the most energy-efficient aerobic pathway for CO2 fixation[J].Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 2014, 111(22): 8239-8244 |

| [65] | Chain P, Lamerdin J, Larimer F, et al. Complete genome sequence of the ammonia-oxidizing bacterium and obligate chemolithoautotroph Nitrosomonas europaea[J].Journal of Bacteriology, 2003, 185(21): 6496-6496 |

| [66] | Schreiber F, Wunderlin P, Udert KM, et al. Nitric oxide and nitrous oxide turnover in natural and engineered microbial communities: biological pathways, chemical reactions, and novel technologies[J].Frontiers in Microbiology, 2012, 3: 372 |

| [67] | Goreau TJ, Kaplan WA, Wofsy SC, et al. Production of NO2? and N2O by nitrifying bacteria at reduced concentrations of oxygen[J].Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 1980, 40(3): 526-532 |

| [68] | L?scher CR, Kock A, K?nneke M, et al. Production of oceanic nitrous oxide by ammonia-oxidizing archaea[J].Biogeosciences, 2012, 9(7): 2419-2429 |

| [69] | Jung MY, Well R, Min D, et al. Isotopic signatures of N2O produced by ammonia-oxidizing archaea from soils[J].The ISME Journal, 2014, 8(5): 1115-1125 |

| [70] | Stieglmeier M, Mooshammer M, Kitzler B, et al. Aerobic nitrous oxide production through N-nitrosating hybrid formation in ammonia-oxidizing archaea[J].The ISME Journal, 2014, 8(5): 1135-1146 |

| [71] | Monteiro M, Séneca J, Magalh?es C. The history of aerobic ammonia oxidizers: from the first discoveries to today[J].Journal of Microbiology, 2014, 52(7): 537-547 |

| [72] | Ji SQ, Liu CG, Zhang XH. The progress and applications of microencapsulation and cultivation of marine microorganisms[J]. Periodical of Ocean University of China, 2010, 40(4): 53-59 (in Chinese)冀世奇, 刘晨光, 张晓华. 海洋微生物微包埋培养及应用研究进展[J].中国海洋大学学报, 2010, 40(4): 53-59 |

2015, Vol. 42

2015, Vol. 42