中国科学院微生物研究所、中国微生物学会主办

文章信息

- 钱丽媛, 李长菲, 罗云敬, 孟颂东

- Qian Liyuan, Li Changfei, Luo Yunjing, Meng Songdong

- 甲胎蛋白在肝癌的诊断和治疗中的研究进展

- Research progress of AFP in the diagnosis and therapy of hepatocellular carcinoma

- 生物工程学报, 2021, 37(9): 3042-3060

- Chinese Journal of Biotechnology, 2021, 37(9): 3042-3060

- 10.13345/j.cjb.210235

-

文章历史

- Received: March 21, 2021

- Accepted: June 7, 2021

- Published: June 21, 2021

2. 中国科学院微生物研究所 中国科学院病原微生物与免疫学重点实验室,北京 100101;

3. 中国科学院大学,北京 100049;

4. 北京康明海慧生物科技有限公司,北京 100081

2. CAS Key Laboratory of Pathogenic Microbiology and Immunology, Institute of Microbiology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100101, China;

3. University of Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100049, China;

4. Beijing Coming Health Bio Technology Co., Ltd., Beijing 100081, China

原发性肝癌,是指原发于肝脏的恶性肿瘤,主要包括肝细胞癌(Hepatocellular carcinoma,HCC)、肝内胆管癌(Intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma,ICC)以及肝细胞和胆管的混合细胞癌(HCC-ICC),是十大恶性肿瘤之一。同时HCC又是最常见的原发性肝癌,HCC占原发性肝癌的85%–90%,因此本文中所指的“肝癌”为HCC[1]。肝癌在世界范围内是第6大常见癌症,也是第3大癌症死亡原因,每年造成约75万人死亡,其中有30万左右病例在我国,在国外的死亡病例大多发生在资源匮乏的撒哈拉以南的非洲国家[2-3]。目前,在我国肝癌是位列第4的常见恶性肿瘤,并且在肿瘤中的致死率排第2,严重威胁我国人民的生命和健康[1]。

肝癌主要是环境因素和遗传因素共同作用的结果[3-4]。肝癌高危人群主要包括:乙型肝炎病毒(HBV) 和(或) 丙型肝炎病毒(HCV) 感染、酗酒、长期食用被黄曲霉毒素污染的食物、非酒精性脂肪性肝炎(Non-alcoholic steatohepatitis,NASH)、肝硬化、Ⅱ型糖尿病、各种肝脏代谢综合征等相关因素以及有肝癌家族史等人群,尤其是年龄大于40岁的男性,其患癌风险更大[1, 3-4]。早期HCC患者可以通过切除、肝移植或消融术治疗,且患者的5年生存率可以达到50%以上。但由于大部分患者发现时已经处于晚期阶段,因而HCC患者的总体生存率仅为20%[4-5]。因此,在高危人群中建立肝癌的早期筛查、诊断和治疗,是提高肝癌的生活质量和生存率的关键[4, 6-7]。肝癌的早期筛查手段主要包括影像学筛查、代谢物分析、病理学诊断和血清学分子标志物检测[1-4]。

影像学筛查的主要特点是:操作简便,灵活直观,敏感度在65%–80%之间,特异性 > 90%,可以在早期敏感地检测出肝内可疑的占位性病变,综合分析检测肝脏的现状[1, 6-7]。医学影像技术虽在HCC的诊断中起着重要的作用,但同时也有其自身的局限性[7]。一方面可能产生一些辐射、检查精度不足等,另一方面,这些检查需要高精度仪器设备、完善配套设施的支持和高水平操作技术人员的配备。目前,大多数肝癌高发人群集中在不发达地区,大面积普及推广医学影像技术非常困难。病理学诊断为有创检测,有着严格的检测条件和操作要求,不适用规模化筛查。因而,肝癌血清学分子标志物的检测依然是十分必要的[1, 6-7]。AFP作为认可度最高的肝癌血清学筛查标志物。在亚太肝脏研究协会(Asian Pacific association for the study of the liver,APASL) 的HCC诊疗手册和我国的《原发性肝癌诊疗规范》中,均强制性要求对AFP进行血清学检测[1, 8-9]。同时,根据国家癌症研究所(National Cancer Institute,NCI) 早期检测研究网络(Early detection research network,EDRN) 采用的5期方案,AFP是唯一一个已通过所有5个阶段的肝癌生物标志物,在肝癌诊疗方面起着重要的作用[10-13]。本文将概述AFP作为HCC血清学标志物,在肝癌的筛查、诊断、预后和治疗等方面的相关功能和临床应用。

1 AFP概述甲胎蛋白(Alpha-fetoprotein,AFP) 是在1956年由Bergstrand和Czar首先利用蛋白电泳的方法从人的胎儿血清中分离出来,由591个氨基酸所组成的多肽链,分子量为68 kDa的血清糖蛋白[14]。AFP是人血清白蛋白家族(Human serum albumin,HSA) 中的一员。该家族编码的基因还包括白蛋白基因(Albumin,ALB)、维生素D结合蛋白(Vitamin D binding protein,DBP) 和维生素E结合蛋白(Alpha albumin,AFM)[15]。这4个基因家族的成员均是从原始基因中产生,他们的外显子和内含子等基因结构表现出高度的保守性[16-17]。同时,在蛋白水平上,该家族成员结构依旧高度保守,如ALB和AFP有40%的同源性。这4种蛋白均是由3个包含180–200个氨基酸的白蛋白结构域组成,分子量范围相近,在ALB (66 kDa)-afamin (82 kDa) 之间,每个结构域包含10个α螺旋,其大小从599个氨基酸(Afamin) 到609个氨基酸(ALB和AFP) 不等,其成员之间蛋白的一级和二级蛋白结构接近,蛋白的理化性质相似[16-17]。AFP作为该家族中的特殊成员,只是在胚胎期或一些病理状态下呈现高表达[18-20]。

在正常生理状态下,AFP存在于胚胎到胎儿的分娩过程中。胚胎期,AFP在胚胎外的内脏卵黄囊、胎儿的肝脏、肠道和肾脏中依次表达[16-17]。因而,关于AFP的正常生理功能的相关研究,都集中在了胚胎期。AFP在胚胎期的作用主要有以下几个方面:首先,AFP作为妊娠期监测胎儿和母体状态的重要血清学标志物。其二,AFP作为一种血清转运蛋白,结合并转运多种分子,如雌激素、脂肪酸、胆红素、类固醇、重金属(铜和镍)、维甲酸、染料黄铜、植物雌雄激素、二噁英、各种环境化合物和某些药物等,在胚胎的生长发育过程中起着重要作用;其三,AFP有免疫抑制作用,通过抑制母体的免疫应答反应,保护胎儿免受母体的免疫攻击[19-20]。

2 AFP在肝癌发生发展中作用机制的研究AFP作为肝癌的诊断标志物,其表达与肝癌的发生发展密切相关。此外,AFP还具有其他多种生物学功能,如影响肝癌细胞的发生发展、调节细胞增殖、迁移、凋亡和免疫逃逸等方面发挥重要作用[18-20]。

2.1 肝癌的发生与AFP基因的表达在非妊娠的状态下健康成年人AFP的水平通常低于10 ng/mL[9-10]。当肝细胞发生癌变后AFP的表达会急剧上升,因此当患者体内持续高水平表达AFP,发生肝癌的概率也会大大增加。因此,作为一种特异性的癌基因,AFP的激活与肝癌之间有很强的相关性[21-22]。AFP的相关调控因子,如肝细胞核因子家族(Hepatocyte nuclear factor,HNF) 成员(如HNF1、HNF3、HNF4和HNF6) 等、肝受体同系物1 (Fetoprotein transcription factor,FTF,又名LRH-1或NR5A2)、CAAT/增强子结合蛋白(CCAAT/enhancer binding protein,C/EBP)、锌指和同源盒2 (Zinc fingers and homeoboxes,Zhx2)、锌指BTB结构域20 (Zinc finger and BTB domain containing 20,Zbtb20) 和p53等,均可直接或间接地影响肝癌的发生[23-26]。研究发现,HBV病毒感染与AFP水平的升高密切相关[27-29]。还有研究者证明一些与炎症或癌症相关的microRNA也可以调控AFP的表达[30-31]。还有一些研究证明AFP的甲基化和乙酰化也与肝癌的发生密切相关[32-33]。

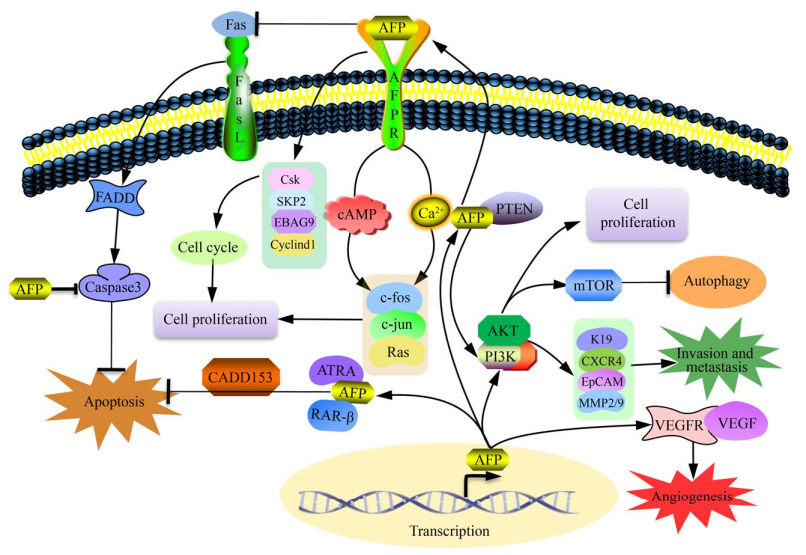

2.2 AFP在肝癌细胞的增殖、侵袭转移和自噬中的研究AFP基因会在肝癌发生后呈现大量表达的现象,因此,AFP在肝癌的发生发展过程中起着重要的作用[19-20]。目前,研究最多的是AFP通过上调/下调相应关键蛋白的表达,如角蛋白19 (Keratin 19,K19)、上皮细胞黏附分子(Epithelial cell adhesion molecule,EpCAM)、基质金属蛋白酶2/9 (Matrix metalloproteinase 2/9,MMP2/9) 和CXC趋化因子受体4 (CXC chemokine receptor 4,CXCR4),或是通过增加血管内皮生长因子(Vascular endothelial growth factor,VEGF)、VEGFR-2和基质金属蛋白酶-2/9 (Matrix metalloproteinases-2/9,MMP2/9) 等,在癌细胞的增殖、侵袭、转移和血管生成等方面影响HCC的发生发展[18-19]。多个团队研究证明AFP通过激活多个细胞信号通路促进肝癌细胞增殖[34-35]。Wang等的研究成果还表明AFP可通过PI3K/Akt/mTOR降低细胞自噬,从而在抑制肝癌细胞自噬和凋亡、促进细胞增殖、迁移和侵袭方面起着重要作用[36]。Zhu等发现AFP通过激活AKT/mTOR信号通路诱导CXCR4表达,继而促进了肝癌细胞的生长和转移[37]。Song等的研究表明,分泌至细胞外的AFP还可以通过与其膜上受体(AFPR) 结合,通过Ca2+和环磷酸腺苷(cAMP) 信号通路诱导癌基因c-fos、c-jun和Ras的表达,或是阻碍抑癌基因蛋白PTEN的功能等,促进HCC细胞的增殖[38]。路欣等还发现AFP可以影响β-连环蛋白(β-catenin) 的mRNA和蛋白水平,从而影响肝癌细胞的分化、侵袭和转移等多个细胞活动[39]。AFP还可以通过阻断Caspase凋亡信号通路、影响凋亡相关基因的表达来抑制癌细胞凋亡[40-42]。Chen等的研究报道,AFP还可以通过抑制HuR介导的Fas/FADD途径影响Caspase信号通路,从而抑制细胞凋亡[43]。此外,还有Wang等的研究证明,AFP还可以通过与PTEN相互作用,激活PI3K/AKT/mTOR信号通路,并通过上调自噬相关蛋白mTOR的表达,抑制肝癌细胞的自噬[44]。图 1表明了AFP在肝癌细胞发生发展过程中的分子机制。目前,众多的研究已经表明,AFP在细胞增殖、凋亡、侵袭、转移、自噬和细胞周期调控等多个方面发挥着重要的作用[18-20]。

|

| 图 1 AFP在肝癌细胞发生发展过程中的分子机制示意图[18-19] Fig. 1 Schematic diagram of the mechanism of AFP in the progress of hepatocellular carcinoma[18-19]. AFP affects the key molecules regulating diverse cellular processes, including cell growth, invasion, metastasis, autophagy, and angiogenesis (┴ stands for inhibition; ↓ stands for stimulation). |

| |

20世纪70年代,Murgita等首先利用亲和层析法证明了AFP是小鼠羊水中的免疫抑制物质[45-46]。此后,Crainie等揭示AFP具有免疫抑制特性,因为AFP能够降低巨噬细胞上抗原的表达水平[47]。大部分肝癌患者的外周血中有大量的AFP存在,这些AFP可以通过抑制免疫细胞功能,从而抑制机体的免疫应答,帮助肝癌细胞逃避免疫监视[48-49]。AFP可以通过抑制DC细胞成熟并诱导其凋亡[49-50]。Suryatenggara等的结果证明AFP可以通过抑制DC细胞的成熟,抑制效应细胞的免疫活性[51]。临床上,González-Carmona等的研究也证明血清中高水平的AFP表达可能引起DC细胞的功能障碍甚至是凋亡,进而抑制了机体的免疫应答反应[52]。AFP通过抑制DC细胞的成熟,影响了T淋巴细胞的分化,改变了CD4+ T和CD8+ T细胞的比例,继而影响T细胞的免疫应答水平[53-55]。Butterfield等的结果表明,即使在高循环水平的癌胚蛋白的环境中,CD8+ T或CD4+ T淋巴细胞也能够识别甲胎蛋白,激活特异性CTL反应并分泌高水平的TNF-α和IFN-γ,并介导了针对肝细胞癌的特异性免疫反应[56-57]。AFP虽然不能直接抑制NK细胞的功能,但通过抑制DC细胞的成熟减少IL-12的分泌量,进而间接地抑制NK细胞的功能[58-59]。

总之,AFP可以通过多种途径抑制机体的免疫应答反应,协助肝癌细胞逃避免疫监视,促进癌细胞在患者体内持续生长[48, 51, 53]。

3 AFP在肝癌临床诊断中的应用目前,AFP作为肝癌诊断中最早发现也是应用广泛的血清学标志物,在肝癌的临床诊断和预后中有着重要的研究价值。

3.1 AFP作为血清学标志物在临床病理诊断中的应用肝癌血清学检测法因敏感性高、特异性强、操作方便及成本低廉等优势,被广泛应用于临床诊断中[60]。1964年Tatarinov和Abelev发现肝细胞癌患者的血清中存在大量的AFP蛋白,并提出把AFP当作原发性肝癌的一个重要的肿瘤标志物[61-62]。目前,AFP已成为肝癌诊断和预后最常见的生物标志物[10-11]。临床上,AFP检测阈值的争论从未间断过。1971年Ruoslahti等首次提出了AFP的血清检测标准。甲胎蛋白的病理学阈值为10.9 μg/L,当血清浓度大于20 μg/L被认为是病理学上的诊断阈值[63]。此外,Trevisani等也在特定的高危人群(肝癌发病率为50%) 筛查中,提出AFP的最佳病理诊断临界值为16–20 μg/L。在这个水平上,特异性高达90%,但敏感性仅为60%,这意味着在这个阈值下,40%的肝癌将被忽略[64]。Gambarin-Gelwan等发现,当采用20 μg/L作为检测阈值时,敏感性和特异性分别为58%和91%,但同时也发现9.2%非肝癌患者AFP水平呈阳性[65]。由于敏感性和特异性呈反比的关系,不同阈值的设定会严重影响到AFP肝癌筛查中假阳性或假阴性比例[66]。

目前,不同的国际肝癌诊疗手册在AFP诊断阈值方面的分歧已经持续数年[1, 6, 67-68]。多个综合诊疗手册表明,AFP的阈值为400 μg/L时,特异性为99%,敏感性为32%,其结果优于其他诊断阈值。如表 1所示,汇总多个临床诊断手册数据后,对不同AFP阈值在肝癌诊断中的特异性和敏感性进行了分析[1, 6, 67-69]。同时,AFP与超声检测的结果也显示,400 μg/L为AFP诊断阈值的推荐指标[1, 6, 67-68]。但不可否认的是就这个检测阈值而言,只有大约20%的肝癌患者显示出如此高的数值[5, 10, 68]。

目前,根据我国的肝癌诊断标准的规定,当AFP的检测数值≥400 μg/L,并排除妊娠、慢性或活动性肝病、生殖腺胚胎源性肿瘤以及消化道肿瘤后,高度提示肝癌[1, 68]。当AFP的检查数值< 400 μg/L的患者,需要配合其他检测。尽量避免早期肝癌的误诊和漏诊等现象的发生。

此外,在一些非肝脏恶性肿瘤中也出现AFP水平升高的现象[20]。例如,当肝细胞出现大量受损、肝炎、慢性肝病或恶性肿瘤,尤其是内皮细胞肝癌、畸胎瘤和胃肠道癌等,都会引起AFP水平的升高[16, 20]。

3.2 AFP的浓度与肝癌的发展进程研究肝癌患者血清中的AFP浓度,一定程度上可以呈现患者肿瘤发生的进程。因此AFP的血清学诊断数据也被认为是一种判断治疗效果的临床敏感指标[70-71]。临床研究表明,AFP的血清学浓度≥400 μg/L的患者,肝癌的预后普遍都较差[20, 69]。

AFP的血清学诊断学研究也同样适用于接受肝移植的肝癌患者[72-73]。Jiao的研究结果显示,在537名肝移植患者的追踪调查中,AFP蛋白可能影响血管浸润和分化,结合AFP的诊断学模型能显著提高肿瘤复发的预测能力[74]。另外,Gurakar等研究发现AFP血清学浓度较高的患者普遍病灶较大,有血管转移现象,且分化程度更高,反之亦然。他们认为,AFP是肝脏移植手术后的患者肝癌是否复发的重要预测因子,有重要的临床研究价值[75]。这些研究提示,血清AFP的诊断学研究在肝癌发展进程中起着重要的作用。因此,研究AFP的生物学功能对于肝癌的治疗和预后有着重要的现实的研究意义[69]。

3.3 AFP mRNA检测在肝癌诊断中的应用AFP mRNA作为肝癌患者的循环外周血肿瘤细胞的替代标记物,已被广泛地应用于逆转录聚合酶链反应(RT-PCR)[76-77]。RT-PCR比免疫组化更敏感,也更快捷方便,在一些特殊患者诊断中会应用到[78-79]。Matsumura等探讨了肝细胞癌患者血液中AFP mRNA的浓度与预后的关系。他们的结果表明24例AFP mRNA阴性患者的累积无转移生存率和总生存率显著高于AFP mRNA持续阳性的30例患者。他们认为,血液中的AFP mRNA是预测HCC患者预后的可靠指标[79]。当然,AFP mRNA对检测HCC的特异性和预后价值还存在争议。争议的原因在于mRNA的体外不稳定性、实验室技术的差异、引物选择、样品收集和处理之间的时间[80]。为了提高检测HCC的可靠性和特异性,通常会使用实时荧光定量RT-PCR方法[80]。除了RT-PCR以外,还有特殊探针标记方法,如巢式PCR法(Nested polymerase chain reaction,PCR)[76-77]。Jin等用巢式PCR法,通过检测肝癌患者血液中的AFP mRNA水平,测定患者血液中的循环肿瘤细胞含量(Circulating tumor cells,CTCs),根据这些数据,评价患者肝癌细胞转移的水平[81]。

目前,将AFP mRNA检测作为一种辅助性检测方法,结合病例特点和病情等具体情况,选择最合适的诊疗方法。

3.4 AFP-L3在肝癌血清学诊断中的研究AFP以多种形式存在于碳水化合物链式结构中,并由此产生AFP异质体。这些碳水化合物是由宿主细胞的一整套糖化酶催化合成的。由于这些酶在不同人体器官中具有异质性,不同组织或肿瘤或是在不同的生理或病理条件,产生的甲胎蛋白数量和种类都可能不同[82-83]。根据凝集素亲和力的不同,AFP家族主要可以分为AFP-L1、AFP-L2和AFP-L3亚型[82-84]。AFP-L1为非凝集素结合组分,是良性肝病、慢性肝炎和肝硬化患者血清中AFP最丰富的亚型;AFP-L2与凝集素有中等亲和力,主要来源于卵黄囊肿瘤,也可以在妊娠期间的母体血清中检测到[83-84]。AFP-L3与凝集素亲和力最高,被证明是一个更具有肝癌特异性的标志物,其特异性为95%[85]。在肝癌诊断过程中,AFP-L3可在肝癌发生9–12个月的时间内提示肝癌的发生[86-87]。

同时AFP-L3还被认为是肝癌恶性程度的重要标志物,当血清中AFP-L3水平较高时,肝癌细胞有早期血管侵袭和肝内转移的倾向[85-86]。血清学与影像学检测联合分析后显示,AFP-L3阳性的肝癌具有快速生长和早期远处转移的潜力,根据这些证据,直径为2 cm的小肝癌在临床上可以被定义为侵袭性肿瘤,如果AFP-L3占AFP总量的10%,那么在临床上可以将其定义为侵袭性癌[87-88]。同时,临床中发现在非恶性慢性肝病中,肝细胞似乎不表达AFP-L3糖型,因此AFP-L3与总AFP的比值较高可能是肿瘤侵袭性的一个指标[86-88]。

此外,ALF-L3同时携带额外的α-1-6岩藻糖苷酶(α-1-6 fucosidase,AFU) 时,是对肝癌监测以及反映肝癌恶性程度的重要标志物,在临床诊断中有重要的应用价值[88-90]。根据我国《原发性肝癌诊疗规范》诊断标准,目前AFP相关检测主要包括α-1-6岩藻糖苷酶和甲胎蛋白异质体L3比率(AFP-L3%) 分析,AFP-L3%≥10%为阳性,AFU > 39.9U/L为阳性[1, 86, 88]。

这种高度特异性AFP-L3的研究又进一步丰富了AFP作为肝癌标志物的研究,对肝癌的早期鉴别诊断有着重大的临床意义[86]。

3.5 AFP与其他血清学标志物的联合应用在肝癌诊断中的研究临床上,AFP的水平升高与包括肝癌在内的多重疾病密切相关,因而单独使用AFP在普通人群中进行筛查,存在广泛的争议[91-92]。

为提高HCC诊断的特异性和准确性,在诊断方案中会加入其他血清学标志物。肝癌的血清学标志物主要包括AFP、AFP-L3、异常凝血酶原(Protein induced by vitamin K absence Ⅱ,PIVKA-Ⅱ)、Glypican-3、GPC-3、Des-γ-羧基凝血酶原(Des-gamma carboxyprothrombin,DCP)、γ-谷氨酰转移酶Ⅱ (γ-glutamyltransferase Ⅱ,γ-GGTⅡ)、α-1-抗胰蛋白酶(α-1-antitrypsin)、Dickkopf相关蛋白1 (Dickkopf-related protein 1,DKK-1) 和血浆游离微小核糖核酸(MicroRNA)等[89-96]。尽管在肝癌的诊断过程中,这些标记物的存在有时是重叠的,但建议至少用两个或3个标记物的联合检测来诊断肝癌的发生[88, 93-94]。Caviglia等的临床研究表明,AFP、AFP-L3和PIVKA-Ⅱ的联合检测对肝癌的诊断优于单一生物标志物[89]。Best等的研究也表明,在GALAD模型中,对早期的患者进行AFP、AFP-L3和DCP的联合检测后,其AUC数值最高甚至达到0.924 2,特异性为93.3%,敏感性为85.6%[97]。如表 2所示,AFP、AFP-L3、DCP的联合检测对肝癌的诊断敏感性和特异性都有明显的提高,检测效果明显优于AFP、AFP-L3或DCP单独检测结果[97]。Fang等应用随机效应模型,系统地分析了AFP、AFP-L3、GP73、DCP和DKK-1这5个生物标志物的联合诊断效果。他们也发现,同时使用AFP、AFP-L3和DCP这3个生物标志物的效果是最好的[96]。

| Biomarkers/combinations | Cut-off value (μg/L) | Viral etiology | Non-viral etiology | |||||

| Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) | DOR | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) | DOR | |||

| AFP | 10 μg/L | 69.4 | 81.6 | 9.7 | 68.4 | 95.3 | 39.0 | |

| 20 μg/L | 55.6 | 90.1 | 10.9 | 59.9 | 98.4 | 69.8 | ||

| AFP-L3 | 10% | 55.6 | 90.6 | 11.4 | 69.5 | 92.6 | 26.6 | |

| DCP | 7.5 μg/L | 44.4 | 98.1 | 33.6 | 65.0 | 91.6 | 19.0 | |

| AFP +DCP |

10 μg/L 7.5 μg/L |

79.6 | 80.2 | 15.0 | 84.7 | 87.9 | 37.8 | |

| 20 μg/L 7.5 μg/L |

68.5 | 88.2 | 15.5 | 80.8 | 90.5 | 37.5 | ||

| AFP +AFP-L3 |

10 μg/L +10% |

78.7 | 78.8 | 13.1 | 83.1 | 90.5 | 43.5 | |

| 20 μg/L +10% |

74.1 | 85.4 | 15.9 | 80.2 | 92.6 | 46.9 | ||

| AFP-L3 +DCP |

10%

+7.5 μg/L |

68.5 | 89.2 | 17.0 | 87.0 | 86.3 | 39.5 | |

| AFP +AFP-L3 +DCP |

10 μg/L +10% +7.5 μg/L |

84.3 | 77.3 | 17.2 | 92.1 | 84.2 | 56.8 | |

| 20 μg/L +10% +7.5 μg/L |

80.6 | 84.0 | 20.5 | 91.0 | 86.3 | 58.2 | ||

| GALAD | –0.63 | 79.6 | 94.3 | 58.5 | 89.3 | 92.1 | 87.5 | |

| DOR: diagnostic odds ratio; GALAD: a logistic regression of diagnostic algorithm based on gender, age, and the biomarkers. | ||||||||

考虑到AFP单个生物标志物得到的数据在特异性、敏感性和应用范围等方面存在问题,多个诊疗手册中提出了AFP联合诊断的要求[1, 6, 67-69]。日本的肝癌临床指南要求AFP纳入临床监测生物标志物联合日本综合分期系统(Japan integrated staging,bm-JIS),进行打分评估。这个评分系统包括AFP、AFP-L3和DCP等,他们认为这种组合对肝癌的诊断具有最佳的特异性和敏感性的平衡,同时可以预测患者的预后水平[98-99]。美国的肝癌临床指南建议血清AFP水平可与超声联合用于筛查高危人群[67]。欧洲的临床诊疗报告结果也指出,将血清学AFP的诊断与超声诊断联合应用后,可以增加6%–8%的肝癌患者检出率[6]。这些研究结果都证明了多种生物标志物对于肝癌的联合诊断的准确性比任何单个生物标志物的分析更具有临床诊断价值。目前,我国的《原发性肝癌诊疗规范》诊断标准建议至少用2–3个标记物的联合检测来诊断肝癌的发生[1, 6, 67-69]。

3.6 AFP作为肝癌的标志物存在的问题在HCC的早期阶段,约30%的病例AFP并未升高,因而其敏感性、特异性和预测价值受到了一定质疑[86]。对于这30%的AFP阴性患者,通常会再联合其他生物标志物筛查[89]。如上文中提到的AFP+AFP-L3+DCP联合诊断法。Best等的研究证明,AFP+DCP+AFP-L3联用后,对于筛查AFP阴性的肝癌患者具有重要作用,肝癌的检测率为68.4%[97]。其他标志物如高尔基蛋白73 (Golgi protein 73,GP73)、黏蛋白1 (Mucin 1,MUC-1)、骨桥蛋白(Osteopontin,OPN)、肝细胞生长因子(Hepatocyte growth factor,HGF)、胰岛素生长因子(Insulin growth factor,IGF)、血管内皮生长因子(Vascular endothelial growth factor,VEGF)、转化生长因子-β1 (Transforming growth factor-beta1,TGF-β1)、MicroRNAs (miRNAs) 和长非编码RNA (Long non-coding RNAs,lncRNAs) 以及我们团队所研究的热休克蛋白相关的诊断标志物等,在肝癌肿瘤早期诊断和疗效评价等方面展现出重要价值[100-102]。

尽管这些检测指标对肝癌的诊断带来更高的准确性,但目前尚未出现能够取代AFP的血清标志物[12, 86, 90]。

4 AFP作为肝癌药物设计靶点或作为癌胚抗原在肝癌免疫治疗方面的应用多年以来,AFP作为一种原癌基因在抗肿瘤尤其是抗肝癌的研究中受到了广泛的关注。

4.1 靶向AFP相关药物研究如上文所述,AFP在促进肝癌细胞的增殖和抗凋亡中均起着重要的作用,因而AFP作为一种肿瘤特异性的靶点在肝癌的靶向药物设计方面有着重要的研究价值[103]。当AFP基因敲除后,细胞增殖受到抑制,早期凋亡细胞数量显著增加,同时Bax/Bcl-2比值升高,线粒体中大量释放细胞色素c,致使p53/Bax/细胞色素c/caspase-3信号通路的功能紊乱[104-106]。AFP靶向治疗在肝癌治疗的联合用药和降低耐药性等方面也起着一定的作用。Li等在研究caspase-3介导的细胞凋亡信号通路中发现,将AFP基因敲除后,增强了TRAIL和全反式维甲酸(All-trans retinoic acid,ATRA) 这些药物对肝癌的化疗效果,解决了肝癌治疗中出现的耐药性问题[107]。Hu等通过构建叶酸-PEI600-环糊精纳米聚合物载体递送系统,特异性靶向AFP蛋白,有效地抑制了肝癌细胞的增殖。经过该团队的评测,这种新型的治疗在体外和体内几乎没有毒性,这些研究为靶向AFP的治疗迈出了新的篇章[108]。

AFP抗体也能够在体外显著抑制肿瘤细胞生长,这一研究结果提示AFP作为肝癌特异性药物设计的靶点,有着重要的研究价值[19-20]。

4.2 AFP在肝癌治疗性疫苗中的研究AFP作为一种特异性的癌胚抗原广泛用于HCC治疗疫苗研究[86, 109-110]。人体自身的免疫系统对自身的AFP具有免疫耐受,因此尽管部分患者中AFP的水平非常高,但患者对该蛋白的免疫应答反应却异常低[111-112]。为了克服这种耐受性,多项关于提高AFP疫苗免疫原性的研究正在进行中。目前针对AFP的相关疫苗主要包括重组质粒DNA、多肽疫苗、嵌合病毒样颗粒、表达AFP蛋白的病毒、细菌载体、DCs疫苗和DC-CIK治疗以及肿瘤特异性T细胞的过继转移等相关[18-19, 109]。如Grimm等尝试用AFP重组痘苗病毒抑制小鼠肝癌,发现通过疫苗免疫后的小鼠肝癌发生了部分的消退[113]。表 3显示了以AFP作为靶抗原的相关肝癌治疗研究。这些早期的研究,初步地探索了AFP在免疫治疗中的应用,为后人的研究打下了坚实的基础[19, 86, 109-110]。

| Treatment | Type | References |

| Adv-AFPsiRNA | Gene therapy | [34] |

| Ad/AFPtBid | Gene therapy | [117] |

| AFP-AdV DNA-based vaccine | Gene therapy | [118] |

| AFP specific DNA-based vaccine | Gene therapy | [113] |

| AFP-specific DNA vaccination | Gene therapy | [119] |

| gp96-AFP protein vaccine | Immunotherapy | [120-121] |

| AFP-derived peptide | Immunotherapy | [103] |

| HSP72/AFP polypeptide | Immunotherapy | [122] |

| DC-DEXAFP | Immunotherapy | [114] |

| AdIL-18/AFP-DC | Immunotherapy | [123] |

| HLA-A*0201 AFP peptide | Immunotherapy | [56-57] |

| AFP peptides DC cells | Cell immunotherapy | [115] |

| DC-CTLs | Cell immunotherapy | [116] |

| AFP-specific T-lymphocytes | T-cell immunotherapy | [124] |

| HLA-A*24:02 AFP-specific T-lymphocytes | T-cell immunotherapy | [125] |

| AFP-specific T-cell receptors (TCRs) | T-cell immunotherapy | [126] |

| AFP(158)-specific TC | T-cell immunotherapy | [127] |

| AFP/HLA-A*02+specific T-cell receptors (TCRs) | T-cell immunotherapy | [128] |

| AFP-MHC complex with CAR T-cell | T-cell immunotherapy | [129] |

DC疫苗因其特异有效的体内免疫应答而显示出良好的应用前景。目前的研究主要集中在如何增强DC细胞的抗原呈递功能,发挥其强大的杀伤HCC细胞的能力[19]。Lu等以AFP为靶抗原,利用一种DC细胞衍生的外泌体(Dendritic cell derived exosomes,DC-DEXs),构建了外泌体免疫治疗疫苗DEXAFP。他们的实验结果表明,这种新型的DEXAFP疫苗可以有效地引起机体的抗原特异性抗肝癌免疫反应,并重塑肝癌小鼠的肿瘤微环境。他们的研究为AFP相关的肝癌的免疫治疗提供了新的研究思路[114]。Butterfield等的一系列临床试验也证明在高循环水平的癌胚蛋白的环境中,人T细胞也能够识别AFP[115]。Wang等用树突状细胞毒性T淋巴细胞(dendritic cell-cytotoxic T lymphocytes,DC-CTL) 对肝癌患者进行治疗后,发现AFP特异T细胞反应能够有效抑制肿瘤细胞的生长,在体内产生强大的保护性免疫效果,因而认为AFP是一个免疫攻击的理想靶点[116]。

4.3 AFP在过继性免疫治疗中的应用临床上,肝癌患者中大约有70%为AFP阳性[130-131]。因而AFP作为一种特异性抗原,为肝癌治疗带来广阔的前景[132-133]。肿瘤的过继性细胞免疫治疗,是近年来被认为最有前景的肿瘤免疫治疗方案,如特异性T细胞(T receptor genes, TCR) 工程和嵌合抗原受体(Chimeric antigen receptor,CAR) T细胞疗法[134-135]。AFP作为一种特异性的癌胚抗原,在肝癌过继性免疫治疗中受到众多的关注[129, 136]。

TCR技术是目前以AFP作为靶点相关的过继性免疫治疗中所采用的主要方案[128, 137]。Li等利用AFP的特异性表位,制备人类HLA特异性T细胞受体工程化T细胞用于肝癌的免疫治疗。他们的结果表明TCR-T细胞能够特异性激活T2细胞和杀伤AFP+HLA-A*24:02肿瘤细胞系[125]。Zhu等的结果证明,AFP特异性TCR的基因具有很大的潜力,用于诱导患者自体T细胞对肝癌进行过继性免疫治疗[126]。

在2020年国际肝脏大会(International Liver Congress 2020,LBO12) 上,Galle等总结了AFPc332T细胞的过继性免疫治疗方案(NCT03132792)。研究人员将患者严格限制在HLA-A 02:01,结果显示4名接受T细胞转输的患者中,1名患者完全缓解,1名患者病情稳定,2名患者有部分疗效[86]。表 4为以AFP为靶抗原的TCR-T细胞在治疗肝癌中的相关临床试验数据。目前,TCR-T细胞治疗最大的制约是HLA分型的限制[86, 134]。据统计,HLA-A 02:01患者只占肝癌患者的40%左右[86]。因此,AFP-TCR-T的发展普及也受到了众多条件的制约。

| Clinical trial | HLA restricted | AFP cut-off (μg/L) | Phase | Age (years) |

Patients numbers | NCTT | Institution |

| ET1402L1 ARTEMISTM2 T cells |

HLA-A02 | 100 | Ⅰ | 18–75 | 12 | NCT03888859 | Xi’an Jiaotong University, China |

| Autologous C-TCR055 T-cells |

HLA-A 02:01 | 200 | Ⅰ | 18–70 | 9 | NCT03971747 | Fudan University, China |

| Autologous C-TCR055 T-cells |

HLA-A 02:01 | 200 | Ⅰ | 18–70 | 3 | NCT04368182 | Zhejiang University, China |

| Autologous modified AFP332 T cells | HLA-A 02:01 | 100 | Ⅰ | 18–75 | 45 | NCT03132792 | Mayo Clinic, United States |

| ET140202 autologous T cell product | HLA-A2 | 200 | Ⅱ | ≥18 | 2 | NCT03998033 | City of Hope Medical Center Duarte, United States |

| TCRe: TCR engineered T cells; HLA: human leucocyte antigen. | |||||||

利用CAR修饰的T细胞靶向实体瘤细胞的治疗已经广泛开展临床研究,且取得了一系列进步[138]。Gao等的研究以AFP作为靶点,应用CAR-T技术,在肝癌的治疗中具有潜在的应用价值[139]。Liu等制备了具有高度选择性和特异性的AFP-CAR,静脉注射AFP-CAR-T细胞于荷瘤NSG小鼠体内。结果显示,这种精准靶向AFP肽-MHC复合物的单链抗体的细胞免疫疗法,有强大的抗肿瘤活性[129]。但是AFP作为一种分泌蛋白,部分患者的血清中大量存在AFP,这为CAR-T相关的免疫治疗蒙上了一层阴影。例如,武汉大学附属人民医院的自体ET1402L1-CAR-T细胞(NCT03349255) 相关临床试验等,目前都没有检索到更进一步的临床研究进展。

4.4 AFP在多个药物联合治疗肝癌中的研究肝癌晚期患者的治疗中,免疫检查点抑制剂单独或联合用药尤为活跃[140]。AFP与多个肿瘤靶标蛋白有相关性,如VEGFR和EpCAM (肝癌干细胞表达标志物)[141]。Yamashita等报道,在血清AFP水平高(> 300 ng/mL) 且EpCAM染色阳性的55例肝癌患者中,他们的VEGF组织表达和微血管密度显著增高[141]。因此,对于AFP水平在400 μg/L以上的患者,可以使用VEGFR-2拮抗剂,如美国食品药品监督管理局(USA Food and Drug Administration,FDA)最近批准的Ramucirumab[142-144]。Melms等研究表明,肝癌患者AFP的水平可以用于预测肝癌患者PD-1抗体的治疗效果[145]。

5 问题与展望AFP自发现以来,在肝癌的发生发展、诊断和治疗等相关领域的研究不断深入,应用范围不断扩大,因而我们对其在肝癌中的研究价值也在不断更新中。

多项研究表明,AFP在促进肝癌的恶化方面起着重要作用。AFP可以通过多种途径影响肝癌细胞的分化、生长、转移、侵袭和凋亡等。同时,AFP作为分泌蛋白在血清中呈现大量表达后,还会影响免疫细胞的功能,成为帮助肝癌细胞逃逸机体的免疫监视的帮凶。因此,AFP也成为众多抗肝癌治疗的新靶点。

目前,关于AFP在肝癌诊断中的研究主要存在最佳AFP阈值的争议及AFP与其他肝癌标志物(如AFP-L3、GP73、DCP或DKK-1) 的联合应用筛查肝癌(尤其在AFP阴性的细胞中) 的问题,值得深入研究哪些组合有更好的敏感性和特异性[146-147]。

同时,AFP作为肝癌治疗的靶标的相关研究是研究热点,针对AFP的相关靶向治疗也一直没有间断过[148],但是AFP作为分泌蛋白的特点也限制了AFP-CAR-T等临床治疗的应用。如果能够降低血清中的AFP水平(如Regorafenib,Nivolumab和Ramucirumab等),再联合过继性免疫治疗等方案,也许能够掀开肝癌治疗的新篇章。随着诊断技术的发展,AFP在肝癌方面的应用也将面对新的挑战和机遇[148-149]。但是,在未来数年内AFP仍然是肝癌的诊断和预后最重要的生物标志物[150]。

| [1] |

中华人民共和国国家卫生健康委员会医政医管局. 原发性肝癌诊疗规范(2019年版). 中华肝脏病杂志, 2020, 28 (2): 112-128. Guidelines for Diagnosis and Treatment of Primary Liver Cancer in China (2019 edition). Zhonghua Gan Zang Bing Za Zhi, 2020, 28(2): 112-128 (in Chinese). |

| [2] |

Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, et al. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin, 2018, 68(6): 394-424. DOI:10.3322/caac.21492

|

| [3] |

Torre LA, Siegel RL, Ward EM, et al. Global cancer incidence and mortality rates and trends——an update. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev, 2016, 25(1): 16-27. DOI:10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-15-0578

|

| [4] |

Forner A, Reig M, Bruix J. Hepatocellular carcinoma. Lancet, 2018, 391(10127): 1301-1314. DOI:10.1016/S0140-6736(18)30010-2

|

| [5] |

Kim JU, Shariff MI, Crossey MM, et al. Hepatocellular carcinoma: review of disease and tumor biomarkers. World J Hepatol, 2016, 8(10): 471-484. DOI:10.4254/wjh.v8.i10.471

|

| [6] |

Galle PR, Forner A, Llovet JM, et al. EASL Clinical Practice Guidelines: management of hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol, 2018, 69(1): 182-236. DOI:10.1016/j.jhep.2018.03.019

|

| [7] |

Foerster F, Galle PR. Comparison of the current international guidelines on the management of HCC. JHEP Rep, 2019, 1(2): 114-119. DOI:10.1016/j.jhepr.2019.04.005

|

| [8] |

Changa AR, Czeisler BM, Lord AS. Management of elevated intracranial pressure: a review. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep, 2019, 19(12): 99. DOI:10.1007/s11910-019-1010-3

|

| [9] |

Kulik L, El-Serag HB. Epidemiology and management of hepatocellular carcinoma. Gastroenterology, 2019, 156(2): 477-491.e1. DOI:10.1053/j.gastro.2018.08.065

|

| [10] |

Piñero F, Dirchwolf M, Pessôa MG. Biomarkers in hepatocellular carcinoma: diagnosis, prognosis and treatment response assessment. Cells, 2020, 9(6): 1370. DOI:10.3390/cells9061370

|

| [11] |

Sengupta S, Parikh ND. Biomarker development for hepatocellular carcinoma early detection: current and future perspectives. Hepat Oncol, 2017, 4(4): 111-122. DOI:10.2217/hep-2017-0019

|

| [12] |

Pepe MS, Etzioni R, Feng Z, et al. Phases of biomarker development for early detection of cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst, 2001, 93(14): 1054-1061. DOI:10.1093/jnci/93.14.1054

|

| [13] |

Lee E, Edward S, Singal AG, et al. Improving screening for hepatocellular carcinoma by incorporating data on levels of α-fetoprotein, over time. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol, 2013, 11(4): 437-440. DOI:10.1016/j.cgh.2012.11.029

|

| [14] |

Bergstrand CG, Czar B. Demonstration of a new protein fraction in serum from the human fetus. Scand J Clin Lab Invest, 1956, 8(2): 174. DOI:10.3109/00365515609049266

|

| [15] |

Deutsch HF. Chemistry and biology of alpha-fetoprotein. Adv Cancer Res, 1991, 56: 253-312.

|

| [16] |

Mizejewski GJ. Biological role of alpha-fetoprotein in cancer: prospects for anticancer therapy. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther, 2002, 2(6): 709-735. DOI:10.1586/14737140.2.6.709

|

| [17] |

Mozzi A, Forni D, Cagliani R, et al. Albuminoid genes: evolving at the interface of dispensability and selection. Genome Biol Evol, 2014, 6(11): 2983-2997. DOI:10.1093/gbe/evu235

|

| [18] |

Zheng Y, Zhu M, Li M. Effects of alpha-fetoprotein on the occurrence and progression of hepatocellular carcinoma. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol, 2020, 146(10): 2439-2446. DOI:10.1007/s00432-020-03331-6

|

| [19] |

Wang XP, Wang QX. Alpha-fetoprotein and hepatocellular carcinoma immunity. Can J Gastroenterol Hepatol, 2018, 2018: 9049252.

|

| [20] |

Sauzay C, Petit A, Bourgeois AM, et al. Alpha-foetoprotein (AFP): a multi-purpose marker in hepatocellular carcinoma. Clin Chim Acta, 2016, 463: 39-44. DOI:10.1016/j.cca.2016.10.006

|

| [21] |

Peterson ML, Ma C, Spear BT. Zhx2 and Zbtb20: novel regulators of postnatal alpha-fetoprotein repression and their potential role in gene reactivation during liver cancer. Semin Cancer Biol, 2011, 21(1): 21-27. DOI:10.1016/j.semcancer.2011.01.001

|

| [22] |

Rebouissou S, Nault JC. Advances in molecular classification and precision oncology in hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol, 2020, 72(2): 215-229. DOI:10.1016/j.jhep.2019.08.017

|

| [23] |

Ishiyama T, Kano J, Minami Y, et al. Expression of HNFs and C/EBP alpha is correlated with immunocytochemical differentiation of cell lines derived from human hepatocellular carcinomas, hepatoblastomas and immortalized hepatocytes. Cancer Sci, 2003, 94(9): 757-763. DOI:10.1111/j.1349-7006.2003.tb01515.x

|

| [24] |

Yu HT, Yu M, Li CY, et al. Specific expression and regulation of hepassocin in the liver and down-regulation of the correlation of HNF1alpha with decreased levels of hepassocin in human hepatocellular carcinoma. J Biol Chem, 2009, 284(20): 13335-13347. DOI:10.1074/jbc.M806393200

|

| [25] |

Xie Z, Zhang H, Tsai W, et al. Zinc finger protein ZBTB20 is a key repressor of alpha-fetoprotein gene transcription in liver. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA, 2008, 105(31): 10859-10864. DOI:10.1073/pnas.0800647105

|

| [26] |

To JC, Chiu AP, Tschida BR, et al. ZBTB20 regulates WNT/CTNNB1 signalling pathway by suppressing PPARG during hepatocellular carcinoma tumourigenesis. JHEP Rep, 2021, 3(2): 100223. DOI:10.1016/j.jhepr.2020.100223

|

| [27] |

Zhu M, Guo J, Li W, et al. HBx induced AFP receptor expressed to activate PI3K/AKT signal to promote expression of Src in liver cells and hepatoma cells. BMC Cancer, 2015, 15: 362. DOI:10.1186/s12885-015-1384-9

|

| [28] |

Zhang C, Chen X, Liu H, et al. Alpha fetoprotein mediates HBx induced carcinogenesis in the hepatocyte cytoplasm. Int J Cancer, 2015, 137(8): 1818-1829. DOI:10.1002/ijc.29548

|

| [29] |

Rungsakulkij N, Suragul W, Mingphruedhi S, et al. Prognostic factors in patients with HBV-related hepatocellular carcinoma following hepatic resection. Infect Agent Cancer, 2018, 13: 20. DOI:10.1186/s13027-018-0192-7

|

| [30] |

Kojima K, Takata A, Vadnais C, et al. MicroRNA122 is a key regulator of α-fetoprotein expression and influences the aggressiveness of hepatocellular carcinoma. Nat Commun, 2011, 2: 338. DOI:10.1038/ncomms1345

|

| [31] |

Parpart S, Roessler S, Dong F, et al. Modulation of miR-29 expression by α-fetoprotein is linked to the hepatocellular carcinoma epigenome. Hepatology, 2014, 60(3): 872-883. DOI:10.1002/hep.27200

|

| [32] |

Chen W, Peng JJ, Ye JN, et al. Aberrant AFP expression characterizes a subset of hepatocellular carcinoma with distinct gene expression patterns and inferior prognosis. J Cancer, 2020, 11(2): 403-413. DOI:10.7150/jca.31435

|

| [33] |

Xue J, Cao Z, Cheng Y, et al. Acetylation of alpha-fetoprotein promotes hepatocellular carcinoma progression. Cancer Lett, 2020, 471: 12-26. DOI:10.1016/j.canlet.2019.11.043

|

| [34] |

Tang H, Tang XY, Liu M, et al. Targeting alpha-fetoprotein represses the proliferation of hepatoma cells via regulation of the cell cycle. Clin Chimica Acta, 2008, 394(1/2): 81-88.

|

| [35] |

Zubkova E, Semenkova L, Dudich E, et al. Alpha-fetoprotein contributes to THP-1 cell invasion and chemotaxis via protein kinase and Gi-protein-dependent pathways. Mol Cell Biochem, 2013, 379(1/2): 283-293.

|

| [36] |

Wang S, Zhu M, Wang Q, et al. Alpha-fetoprotein inhibits autophagy to promote malignant behaviour in hepatocellular carcinoma cells by activating PI3K/AKT/mTOR signalling. Cell Death Dis, 2018, 9(10): 1027. DOI:10.1038/s41419-018-1036-5

|

| [37] |

Zhu M, Guo J, Xia H, et al. Alpha-fetoprotein activates AKT/mTOR signaling to promote CXCR4 expression and migration of hepatoma cells. Oncoscience, 2015, 2(1): 59-70. DOI:10.18632/oncoscience.115

|

| [38] |

Song W, Song C, Chen Y, et al. Polysaccharide-induced apoptosis in H22 cells through G2/M arrest and BCL2/BAX caspase-activated Fas pathway. Cell Mol Biol (Noisy-Le-Grand), 2015, 61(7): 88-95.

|

| [39] |

路欣, 孔令玉, 刘殿卿, 等. D-双功能蛋白在肝癌组织中的表达及其与AFP和CA19-9的相关性. 临床肝胆病杂志, 2018, 34(10): 2153-2156. Lu X, Kong LY, Liu DQ, et al. Expression of D-bifunctional protein in hepatocellular carcinoma tissue and its correlation with alpha-fetoprotein and carbohydrate antigen 19-9. J Clin Hepatol, 2018, 34(10): 2153-2156 (in Chinese). DOI:10.3969/j.issn.1001-5256.2018.10.018 |

| [40] |

Lin B, Zhu M, Wang W, et al. Structural basis for alpha fetoprotein-mediated inhibition of caspase-3 activity in hepatocellular carcinoma cells. Int J Cancer, 2017, 141(7): 1413-1421. DOI:10.1002/ijc.30850

|

| [41] |

Li MS, Zhou S, Liu XH, et al. Alpha-fetoprotein shields hepatocellular carcinoma cells from apoptosis induced by tumor necrosis factor-related apoptosis-inducing ligand. Cancer Lett, 2007, 249(2): 227-234. DOI:10.1016/j.canlet.2006.09.004

|

| [42] |

Li CY, Wang SS, Jiang W, et al. Impact of intracellular alpha fetoprotein on retinoic acid receptors-mediated expression of GADD153 in human hepatoma cell lines. Int J Cancer, 2012, 130(4): 754-764. DOI:10.1002/ijc.26025

|

| [43] |

Chen T, Dai X, Dai J, et al. AFP promotes HCC progression by suppressing the HuR-mediated Fas/FADD apoptotic pathway. Cell Death Dis, 2020, 11(10): 822. DOI:10.1038/s41419-020-03030-7

|

| [44] |

Wang SS, Chen YH, Chen N, et al. Hydrogen sulfide promotes autophagy of hepatocellular carcinoma cells through the PI3K/Akt/mTOR signaling pathway. Cell Death Dis, 2017, 8(3): e2688. DOI:10.1038/cddis.2017.18

|

| [45] |

Murgita RA, Tomasi TB. Suppression of the immune response by alpha-fetoprotein on the primary and secondary antibody response. J Exp Med, 1975, 141(2): 269-286. DOI:10.1084/jem.141.2.269

|

| [46] |

Murgita RA, Wigzell H. Selective immunoregulatory properties of alpha-fetoprotein. Ric Clin Lab, 1979, 9(4): 327-342. DOI:10.1007/BF02904569

|

| [47] |

Crainie M, Semeluk A, Lee KC, et al. Regulation of constitutive and lymphokine-induced Ia expression by murine α-fetoprotein. Cell Immunol, 1989, 118(1): 41-52. DOI:10.1016/0008-8749(89)90356-0

|

| [48] |

Meng W, Bai B, Bai Z, et al. The immunosuppression role of alpha-fetoprotein in human hepatocellular carcinoma. Discov Med, 2016, 21(118): 489-494.

|

| [49] |

Santos PM, Menk AV, Shi J, et al. Tumor-derived α-fetoprotein suppresses fatty acid metabolism and oxidative phosphorylation in dendritic cells. Cancer Immunol Res, 2019, 7(6): 1001-1012. DOI:10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-18-0513

|

| [50] |

Li CL, Song BB, Santos PM, et al. Hepatocellular cancer-derived alpha fetoprotein uptake reduces CD1 molecules on monocyte-derived dendritic cells. Cell Immunol, 2019, 335: 59-67. DOI:10.1016/j.cellimm.2018.10.011

|

| [51] |

Suryatenggara J, Wibowo H, Atmodjo WL, et al. Characterization of alpha-fetoprotein effects on dendritic cell and its function as effector immune response activator. J Hepatocell Carcinoma, 2017, 4: 139-151. DOI:10.2147/JHC.S139070

|

| [52] |

González-Carmona MA, Märten A, Hoffmann P, et al. Patient-derived dendritic cells transduced with an a-fetoprotein-encoding adenovirus and co-cultured with autologous cytokine-induced lymphocytes induce a specific and strong immune response against hepatocellular carcinoma cells. Liver Int, 2006, 26(3): 369-379. DOI:10.1111/j.1478-3231.2005.01235.x

|

| [53] |

Chereshnev VA, Timganova VP, Zamorina SA, et al. Role of α-fetoprotein in differentiation of regulatory T lymphocytes. Doklady Biol Sci, 2017, 477(1): 248-251. DOI:10.1134/S0012496617060084

|

| [54] |

Chen KJ, Zhou L, Xie HY, et al. Intratumoral regulatory T cells alone or in combination with cytotoxic T cells predict prognosis of hepatocellular carcinoma after resection. Med Oncol, 2012, 29(3): 1817-1826. DOI:10.1007/s12032-011-0006-x

|

| [55] |

Bray SM, Vujanovic L, Butterfield LH. Dendritic cell-based vaccines positively impact natural killer and regulatory T cells in hepatocellular carcinoma patients. Clin Dev Immunol, 2011, 2011: 249281.

|

| [56] |

Butterfield LH, Meng WS, Koh A, et al. T cell responses to HLA-A*0201-restricted peptides derived from human alpha fetoprotein. J Immunol, 2001, 166(8): 5300-5308. DOI:10.4049/jimmunol.166.8.5300

|

| [57] |

Butterfield LH, Ribas A, Meng WS, et al. T-cell responses to HLA-A*0201 immunodominant peptides derived from alpha-fetoprotein in patients with hepatocellular cancer. Clin Cancer Res, 2003, 9(16 Pt 1): 5902-5908.

|

| [58] |

Yamamoto M, Tatsumi T, Miyagi T, et al. Α-fetoprotein impairs activation of natural killer cells by inhibiting the function of dendritic cells. Clin Exp Immunol, 2011, 165(2): 211-219. DOI:10.1111/j.1365-2249.2011.04421.x

|

| [59] |

Guerra N, Tan YX, Joncker NT, et al. NKG2D-deficient mice are defective in tumor surveillance in models of spontaneous malignancy. Immunity, 2008, 28(4): 571-580. DOI:10.1016/j.immuni.2008.02.016

|

| [60] |

De Stefano F, Chacon E, Turcios L, et al. Novel biomarkers in hepatocellular carcinoma. Dig Liver Dis, 2018, 50(11): 1115-1123. DOI:10.1016/j.dld.2018.08.019

|

| [61] |

Tatarinov Y. Detection of embryo specific globulin in the blood sera of patients with primary liver tumors. Vopr Med Khin, 1964, 10: 90-91.

|

| [62] |

Abelev GI. Alpha-fetoprotein in ontogenesis and its association with malignant tumors. Adv Cancer Res, 1971, 14: 295-358.

|

| [63] |

Ruoslahti E, Seppälä M. Alpha-fetoprotein in cancer and fetal development. Adv Cancer Res, 1979, 29: 275-346.

|

| [64] |

Trevisani F, D'Intino PE, Morselli-Labate AM, et al. Serum alpha-fetoprotein for diagnosis of hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with chronic liver disease: influence of HBsAg and anti-HCV status. J Hepatol, 2001, 34(4): 570-575. DOI:10.1016/S0168-8278(00)00053-2

|

| [65] |

Gambarin-Gelwan M, Wolf DC, Shapiro R, et al. Sensitivity of commonly available screening tests in detecting hepatocellular carcinoma in cirrhotic patients undergoing liver transplantation. Am J Gastroenterol, 2000, 95(6): 1535-1538. DOI:10.1111/j.1572-0241.2000.02091.x

|

| [66] |

Ayuso C, Rimola J, Vilana R, et al. Diagnosis and staging of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC): current guidelines. Eur J Radiol, 2018, 101: 72-81. DOI:10.1016/j.ejrad.2018.01.025

|

| [67] |

Heimbach JK, Kulik LM, Finn RS, et al. AASLD guidelines for the treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology, 2018, 67(1): 358-380. DOI:10.1002/hep.29086

|

| [68] |

Xie DY, Ren ZG, Zhou J, et al. 2019 Chinese clinical guidelines for the management of hepatocellular carcinoma: updates and insights. Hepatobiliary Surg Nutr, 2020, 9(4): 452-463. DOI:10.21037/hbsn-20-480

|

| [69] |

Kanwal F, Singal AG. Surveillance for hepatocellular carcinoma: current best practice and future direction. Gastroenterology, 2019, 157(1): 54-64. DOI:10.1053/j.gastro.2019.02.049

|

| [70] |

Wang W, Wei C. Advances in the early diagnosis of hepatocellular carcinoma. Genes Dis, 2020, 7(3): 308-319. DOI:10.1016/j.gendis.2020.01.014

|

| [71] |

Dieckmann KP, Anheuser P, Simonsen H, et al. Pure testicular seminoma with non-pathologic elevation of alpha fetoprotein: a case series. Urol Int, 2017, 99(3): 353-357. DOI:10.1159/000478706

|

| [72] |

Özdemir F, Baskiran A. The importance of AFP in liver transplantation for HCC. J Gastrointest Cancer, 2020, 51(4): 1127-1132. |

| [73] |

Berry K, Ioannou GN. Serum alpha-fetoprotein level independently predicts posttransplant survival in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Liver Transpl, 2013, 19(6): 634-645. DOI:10.1002/lt.23652

|

| [74] |

Jiao LR. Percutaneous microwave ablation liver partition and portal vein embolization for rapid liver regeneration: a minimally invasive first step of ALPPS for hepatocellular carcinoma. Ann Surg, 2016, 264(1): e3. DOI:10.1097/SLA.0000000000001718

|

| [75] |

Gurakar A, Ma M, Garonzik-Wang J, et al. Clinicopathological distinction of low-AFP- secreting vs. high-AFP-secreting hepatocellular carcinomas. Ann Hepatol, 2018, 17(6): 1052-1066. DOI:10.5604/01.3001.0012.7206

|

| [76] |

Kobayashi S, Tomokuni A, Takahashi H, et al. The clinical significance of alpha-fetoprotein mRNAs in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Gastrointest Tumors, 2017, 3(3/4): 141-152.

|

| [77] |

Luo J, Yang K, Wen YG. Nested polymerase chain reaction technique for the detection of Gpc3 and Afp mRNA in liver cancer micrometastases. Genet Mol Res, 2017, 16(1): gmr16018947.

|

| [78] |

Lemoine A, Le Bricon T, Salvucci M, et al. Prospective evaluation of circulating hepatocytes by alpha-fetoprotein mRNA in humans during liver surgery. Ann Surg, 1997, 226(1): 43-50. DOI:10.1097/00000658-199707000-00006

|

| [79] |

Matsumura M, Shiratori Y, Niwa Y, et al. Presence of α-fetoprotein mRNA in blood correlates with outcome in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol, 1999, 31(2): 332-339. DOI:10.1016/S0168-8278(99)80232-3

|

| [80] |

Benoy IH, Elst H, Van Dam P, et al. Detection of circulating tumour cells in blood by quantitative real-time RT-PCR: effect of pre-analytical time. Clin Chem Lab Med, 2006, 44(9): 1082-1087.

|

| [81] |

Jin J, Niu X, Zou L, et al. AFP mRNA level in enriched circulating tumor cells from hepatocellular carcinoma patient blood samples is a pivotal predictive marker for metastasis. Cancer Lett, 2016, 378(1): 33-37. DOI:10.1016/j.canlet.2016.04.033

|

| [82] |

Terentiev AA, Moldogazieva NT. Structural and functional mapping of alpha-fetoprotein. Biochemistry (Mosc), 2006, 71(2): 120-132. DOI:10.1134/S0006297906020027

|

| [83] |

Gillespie JR, Uversky VN. Structure and function of alpha-fetoprotein: a biophysical overview. Biochim Biophys Acta, 2000, 1480(1/2): 41-56.

|

| [84] |

Li D, Mallory T, Satomura S. AFP-L3: a new generation of tumor marker for hepatocellular carcinoma. Clin Chim Acta, 2001, 313(1/2): 15-19.

|

| [85] |

Yuen MF, Lai CL. Serological markers of liver cancer. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol, 2005, 19(1): 91-99. DOI:10.1016/j.bpg.2004.10.003

|

| [86] |

Galle PR, Foerster F, Kudo M, et al. Biology and significance of alpha-fetoprotein in hepatocellular carcinoma. Liver Int, 2019, 39(12): 2214-2229. DOI:10.1111/liv.14223

|

| [87] |

Bertino G, Ardiri A, Malaguarnera M, et al. Hepatocellualar carcinoma serum markers. Semin Oncol, 2012, 39(4): 410-433. DOI:10.1053/j.seminoncol.2012.05.001

|

| [88] |

Trevisani F, Garuti F, Neri A. Alpha-fetoprotein for diagnosis, prognosis, and transplant selection. Semin Liver Dis, 2019, 39(2): 163-177. DOI:10.1055/s-0039-1677768

|

| [89] |

Caviglia GP, Abate ML, Petrini E, et al. Highly sensitive alpha-fetoprotein, Lens culinaris agglutinin-reactive fraction of alpha-fetoprotein and des-gamma-carboxyprothrombin for hepatocellular carcinoma detection. Hepatol Res, 2016, 46(3): E130-E135. DOI:10.1111/hepr.12544

|

| [90] |

Marrero JA, Feng Z, Wang Y, et al. Alpha-fetoprotein, des-gamma carboxyprothrombin, and lectin-bound alpha-fetoprotein in early hepatocellular carcinoma. Gastroenterology, 2009, 137(1): 110-118. DOI:10.1053/j.gastro.2009.04.005

|

| [91] |

Llovet JM, Montal R, Sia D, et al. Molecular therapies and precision medicine for hepatocellular carcinoma. Nat Rev Clin Oncol, 2018, 15(10): 599-616. DOI:10.1038/s41571-018-0073-4

|

| [92] |

Longerich T. Hepatocellular carcinoma. Der Pathol, 2020, 41(5): 478-487.

|

| [93] |

Caviglia GP, Ciruolo M, Abate ML, et al. Alpha-fetoprotein, protein induced by vitamin K absence or antagonist Ⅱ and glypican-3 for the detection and prediction of hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with cirrhosis of viral etiology. Cancers, 2020, 12(11): 3218. DOI:10.3390/cancers12113218

|

| [94] |

Park SJ, Jang JY, Jeong SW, et al. Usefulness of AFP, AFP-L3, and PIVKA-Ⅱ, and their combinations in diagnosing hepatocellular carcinoma. Medicine (Baltimore), 2017, 96(11): e5811. DOI:10.1097/MD.0000000000005811

|

| [95] |

Kotwani P, Chan W, Yao F, et al. DCP and AFP-L3 are complementary to AFP in predicting high-risk explant features: results of a prospective study. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol, 2021, S1542-3565. DOI:10.1016/j.cgh.2021.01.043

|

| [96] |

Fang YS, Wu Q, Zhao HC, et al. Do combined assays of serum AFP, AFP-L3, DCP, GP73, and DKK-1 efficiently improve the clinical values of biomarkers in decision-making for hepatocellular carcinoma? A meta-analysis. Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol, 2021, 15(9): 1065-1076. DOI:10.1080/17474124.2021.1900731

|

| [97] |

Best J, Bilgi H, Heider D, et al. The GALAD scoring algorithm based on AFP, AFP-L3, and DCP significantly improves detection of BCLC early stage hepatocellular carcinoma. Z Gastroenterol, 2016, 54(12): 1296-1305. DOI:10.1055/s-0042-119529

|

| [98] |

Kitai S, Kudo M, Minami Y, et al. Validation of a new prognostic staging system for hepatocellular carcinoma: a comparison of the biomarker- combined Japan integrated staging score, the conventional Japan integrated staging score and the BALAD score. Oncology, 2008, 75(Suppl 1): 83-90.

|

| [99] |

Kitai S, Kudo M, Izumi N, et al. Validation of three staging systems for hepatocellular carcinoma (JIS score, biomarker-combined JIS score and BCLC system) in 4, 649 cases from a Japanese nationwide survey. Dig Dis, 2014, 32(6): 717-724. DOI:10.1159/000368008

|

| [100] |

Von Felden J, Garcia-Lezana T, Schulze K, et al. Liquid biopsy in the clinical management of hepatocellular carcinoma. Gut, 2020, 69(11): 2025-2034. DOI:10.1136/gutjnl-2019-320282

|

| [101] |

Wang T, Zhang KH. New blood biomarkers for the diagnosis of AFP-negative hepatocellular carcinoma. Front Oncol, 2020, 10: 1316. DOI:10.3389/fonc.2020.01316

|

| [102] |

Luo P, Wu S, Yu Y, et al. Current status and perspective biomarkers in AFP negative HCC: towards screening for and diagnosing hepatocellular carcinoma at an earlier stage. Pathol Oncol Res, 2020, 26(2): 599-603. DOI:10.1007/s12253-019-00585-5

|

| [103] |

Mizejewskia GJ, Butterstein G. Survey of functional activities of alpha-fetoprotein derived growth inhibitory peptides: review and prospects. Curr Protein Pept Sci, 2006, 7(1): 73-100. DOI:10.2174/138920306775474130

|

| [104] |

Gao P, Wang R, Shen JJ, et al. Hypoxia-inducible enhancer/alpha-fetoprotein promoter-driven RNA interference targeting STK15 suppresses proliferation and induces apoptosis in human hepatocellular carcinoma cells. Cancer Sci, 2008, 99(11): 2209-2217. DOI:10.1111/j.1349-7006.2008.00941.x

|

| [105] |

Yang X, Zhang Y, Zhang L, et al. Silencing alpha-fetoprotein expression induces growth arrest and apoptosis in human hepatocellular cancer cell. Cancer Lett, 2008, 271(2): 281-293. DOI:10.1016/j.canlet.2008.06.017

|

| [106] |

Yang XJ, Chen L, Liang YH, et al. Knockdown of alpha-fetoprotein expression inhibits HepG2 cell growth and induces apoptosis. J Cancer Res Ther, 2018, 14(Supplement): S634-S643.

|

| [107] |

Li M, Li H, Li C, et al. Alpha fetoprotein is a novel protein-binding partner for caspase-3 and blocks the apoptotic signaling pathway in human hepatoma cells. Int J Cancer, 2009, 124(12): 2845-2854. DOI:10.1002/ijc.24272

|

| [108] |

Hu BG, Liu LP, Chen GG, et al. Therapeutic efficacy of improved α-fetoprotein promoter-mediated tBid delivered by folate-PEI600-cyclodextrin nanopolymer vector in hepatocellular carcinoma. Exp Cell Res, 2014, 324(2): 183-191. DOI:10.1016/j.yexcr.2014.04.005

|

| [109] |

Zhang L, Ding J, Li HY, et al. Immunotherapy for advanced hepatocellular carcinoma, where are we?. Biochim et Biophys Acta Rev Cancer, 2020, 1874(2): 188441. DOI:10.1016/j.bbcan.2020.188441

|

| [110] |

Sim HW, Knox J. Hepatocellular carcinoma in the era of immunotherapy. Curr Probl Cancer, 2018, 42(1): 40-48. DOI:10.1016/j.currproblcancer.2017.10.007

|

| [111] |

Han YM, Chen ZB, Yang Y, et al. Human CD14+CTLA-4+ regulatory dendritic cells suppress T-cell response by cytotoxic T-lymphocyte antigen-4-dependent IL-10 and indoleamine-2, 3-dioxygenase production in hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology, 2014, 59(2): 567-579. DOI:10.1002/hep.26694

|

| [112] |

Pardee A, Shi J, Butterfield L. Tumor-derived alpha-fetoprotein impairs the differentiation and T cell stimulatory activity of human dendritic cells. J Immunother Cancer, 2014, 2(suppl 3): P229.

|

| [113] |

Grimm CF, Ortmann D, Mohr L, et al. Mouse alpha-fetoprotein-specific DNA-based immunotherapy of hepatocellular carcinoma leads to tumor regression in mice. Gastroenterology, 2000, 119(4): 1104-1112. DOI:10.1053/gast.2000.18157

|

| [114] |

Lu Z, Zuo B, Jing R, et al. Dendritic cell-derived exosomes elicit tumor regression in autochthonous hepatocellular carcinoma mouse models. J Hepatol, 2017, 67(4): 739-748. DOI:10.1016/j.jhep.2017.05.019

|

| [115] |

Butterfield LH, Ribas A, Dissette VB, et al. A phase Ⅰ/Ⅱ trial testing immunization of hepatocellular carcinoma patients with dendritic cells pulsed with four alpha-fetoprotein peptides. Clin Cancer Res, 2006, 12(9): 2817-2825. DOI:10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-2856

|

| [116] |

Wang Y, Yang XJ, Yu Y, et al. Immunotherapy of patient with hepatocellular carcinoma using cytotoxic T lymphocytes ex vivo activated with tumor antigen-pulsed dendritic cells. J Cancer, 2018, 9(2): 275-287. DOI:10.7150/jca.22176

|

| [117] |

Ma SH, Chen GG, Yip J, et al. Therapeutic effect of α-fetoprotein promoter-mediated tBid and chemotherapeutic agents on orthotopic liver tumor in mice. Gene Ther, 2010, 17(7): 905-912. DOI:10.1038/gt.2010.34

|

| [118] |

Butterfield LH, Economou JS, Gamblin TC, et al. Alpha fetoprotein DNA prime and adenovirus boost immunization of two hepatocellular cancer patients. J Transl Med, 2014, 12: 86. DOI:10.1186/1479-5876-12-86

|

| [119] |

Hanke P, Serwe M, Dombrowski F, et al. DNA vaccination with AFP-encoding plasmid DNA prevents growth of subcutaneous AFP-expressing tumors and does not interfere with liver regeneration in mice. Cancer Gene Ther, 2002, 9(4): 346-355. DOI:10.1038/sj.cgt.7700445

|

| [120] |

Wang XP, Wang QX, Lin HP, et al. Glycoprotein 96 and α-fetoprotein cross-linking complexes elicited specific antitumor immunity. Cancer Biother Radiopharm, 2013, 28(5): 406-414. DOI:10.1089/cbr.2012.1404

|

| [121] |

Hirayama M, Nishimura Y. The present status and future prospects of peptide-based cancer vaccines. Int Immunol, 2016, 28(7): 319-328. DOI:10.1093/intimm/dxw027

|

| [122] |

Li Z, Wang XP, Lin HP, et al. Anti-tumor immunity elicited by cross-linking vaccine heat shock protein 72 and alpha-fetoprotein epitope peptide. Neoplasma, 2015, 62(5): 713-721. DOI:10.4149/neo_2015_085

|

| [123] |

Cao DY, Yang JY, Dou KF, et al. Α-fetoprotein and interleukin-18 gene-modified dendritic cells effectively stimulate specific type-1 CD4- and CD8-mediated T-cell response from hepatocellular carcinoma patients in vitro. Hum Immunol, 2007, 68(5): 334-341. DOI:10.1016/j.humimm.2007.01.008

|

| [124] |

Hanke P, Rabe C, Serwe M, et al. Cirrhotic patients with or without hepatocellular carcinoma harbour AFP-specific T-lymphocytes that can be activated in vitro by human alpha-fetoprotein. Scand J Gastroenterol, 2002, 37(8): 949-955. DOI:10.1080/003655202760230928

|

| [125] |

Li Z, Gong H, Liu Q, et al. Identification of an HLA-A*24:02-restricted α-fetoprotein signal peptide -derived antigen and its specific T-cell receptor for T-cell immunotherapy. Immunology, 2020, 159(4): 384-392. DOI:10.1111/imm.13168

|

| [126] |

Zhu W, Peng YB, Wang L, et al. Identification of α-fetoprotein-specific T-cell receptors for hepatocellular carcinoma immunotherapy. Hepatology, 2018, 68(2): 574-589. DOI:10.1002/hep.29844

|

| [127] |

Cai L, Caraballo Galva LD, Peng YB, et al. Preclinical studies of the off-target reactivity of AFP158-specific TCR engineered T cells. Front Immunol, 2020, 11: 607. DOI:10.3389/fimmu.2020.00607

|

| [128] |

Docta RY, Ferronha T, Sanderson JP, et al. Tuning T-cell receptor affinity to optimize clinical risk-benefit when targeting alpha-fetoprotein- positive liver cancer. Hepatology, 2019, 69(5): 2061-2075. DOI:10.1002/hep.30477

|

| [129] |

Liu H, Xu YY, Xiang JY, et al. Targeting alpha-fetoprotein (AFP)-MHC complex with CAR T-cell therapy for liver cancer. Clin Cancer Res, 2017, 23(2): 478-488. DOI:10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-16-1203

|

| [130] |

Bruix J, Gores GJ, Mazzaferro V. Hepatocellular carcinoma: clinical frontiers and perspectives. Gut, 2014, 63(5): 844-855. DOI:10.1136/gutjnl-2013-306627

|

| [131] |

Bouattour M, Mehta N, He AR, et al. Systemic treatment for advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. Liver Cancer, 2019, 8(5): 341-358. DOI:10.1159/000496439

|

| [132] |

刘允怡, 赖俊雄, 梁惠棠. 全身免疫化疗治疗肝癌的效果. 中国普外基础与临床杂志, 2006, 13(2): 129-131. Liu YY, Lai JX, Liang HT. Systemic chemo-immunotherapy for hepatocellular carcinoma. Chin J Bases Clin Gen Surg, 2006, 13(2): 129-131 (in Chinese). DOI:10.3969/j.issn.1007-9424.2006.02.002 |

| [133] |

Hilmi M, Vienot A, Rousseau B, et al. Immune therapy for liver cancers. Cancers (Basel), 2019, 12(1): E77. DOI:10.3390/cancers12010077

|

| [134] |

Ping Y, Liu C, Zhang Y. T-cell receptor-engineered T cells for cancer treatment: current status and future directions. Protein Cell, 2018, 9(3): 254-266. DOI:10.1007/s13238-016-0367-1

|

| [135] |

Xu Q, Harto H, Berahovich R, et al. Generation of CAR-T cells for cancer immunotherapy. Methods Mol Biol, 2019, 1884: 349-360.

|

| [136] |

Luo X, Cui H, Cai L, et al. Selection of a clinical lead TCR targeting alpha-fetoprotein-positive liver cancer based on a balance of risk and benefit. Front Immunol, 2020, 11: 623. DOI:10.3389/fimmu.2020.00623

|

| [137] |

Rochigneux P, Chanez B, De Rauglaudre B, et al. Adoptive cell therapy in hepatocellular carcinoma: biological rationale and first results in early phase clinical trials. Cancers, 2021, 13(2): 271. DOI:10.3390/cancers13020271

|

| [138] |

Martinez M, Moon EK. CAR T cells for solid tumors: new strategies for finding, infiltrating, and surviving in the tumor microenvironment. Front Immunol, 2019, 10: 128. DOI:10.3389/fimmu.2019.00128

|

| [139] |

Gao H, Li K, Tu H, et al. Development of T cells redirected to glypican-3 for the treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res, 2014, 20(24): 6418-6428. DOI:10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-14-1170

|

| [140] |

Zhu AX, Nipp RD, Finn RS, et al. Ramucirumab in the second-line for patients with hepatocellular carcinoma and elevated alpha-fetoprotein: patient-reported outcomes across two randomised clinical trials. ESMO Open, 2020, 5(4): e000797. DOI:10.1136/esmoopen-2020-000797

|

| [141] |

Yamashita T, Forgues M, Wang W, et al. EpCAM and alpha-fetoprotein expression defines novel prognostic subtypes of hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Res, 2008, 68(5): 1451-1461. DOI:10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-6013

|

| [142] |

Zhu AX, Park JO, Ryoo BY, et al. Ramucirumab versus placebo as second-line treatment in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma following first-line therapy with sorafenib (REACH): a randomised, double-blind, multicentre, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol, 2015, 16(7): 859-870. DOI:10.1016/S1470-2045(15)00050-9

|

| [143] |

Syed YY. Ramucirumab: a review in hepatocellular carcinoma. Drugs, 2020, 80(3): 315-322. DOI:10.1007/s40265-020-01263-6

|

| [144] |

Lima LDP, Machado CJ, Rodrigues JBSR, et al. Immunohistochemical coexpression of epithelial cell adhesion molecule and alpha-fetoprotein in hepatocellular carcinoma. Can J Gastroenterol Hepatol, 2018, 2018: 5970852.

|

| [145] |

Melms JC, Thummalapalli R, Shaw K, et al. Alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) as tumor marker in a patient with urothelial cancer with exceptional response to anti-PD-1 therapy and an escape lesion mimic. J Immunother Cancer, 2018, 6(1): 89. DOI:10.1186/s40425-018-0394-y

|

| [146] |

Wang XY, Zhang YY, Yang N, et al. Evaluation of the combined application of AFP, AFP-L3%, and DCP for hepatocellular carcinoma diagnosis: a meta-analysis. Biomed Res Int, 2020, 2020: 5087643.

|

| [147] |

West CA, Black AP, Mehta AS. Analysis of hepatocellular carcinoma tissue for biomarker discovery[M]//HOSHIDA Y. Hepatocellular Carcinoma: translational precision medicine approaches. Cham (CH); Humana Press Copyright 2019, Springer Nature Switzerland AG. 2019: 93-107.

|

| [148] |

Sonbol MB, Riaz IB, Naqvi SAA, et al. Systemic therapy and sequencing options in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. JAMA Oncol, 2020, 6(12): e204930. DOI:10.1001/jamaoncol.2020.4930

|

| [149] |

Bangaru S, Marrero JA, Singal AG. Review article: new therapeutic interventions for advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. Aliment Pharmacol Ther, 2020, 51(1): 78-89. DOI:10.1111/apt.15573

|

| [150] |

Becker-Assmann J, Fard-Aghaie MH, Kantas A, et al. Diagnostic and prognostic significance of α-fetoprotein in hepatocellular carcinoma. Chirurg, 2020, 91(9): 769-777. DOI:10.1007/s00104-020-01118-6

|

2021, Vol. 37

2021, Vol. 37