中国科学院微生物研究所、中国微生物学会主办

文章信息

- 张景琰, 段燕文, 朱湘成, 颜晓晖

- Zhang Jingyan, Duan Yanwen, Zhu Xiangcheng, Yan Xiaohui

- 新型angucycline/angucyclinone类天然产物的研究进展(2010–2020)

- Novel angucycline/angucyclinone family of natural products discovered between 2010 and 2020

- 生物工程学报, 2021, 37(6): 2147-2165

- Chinese Journal of Biotechnology, 2021, 37(6): 2147-2165

- 10.13345/j.cjb.210033

-

文章历史

- Received: January 11, 2021

- Accepted: March 16, 2021

2. 组合生物合成与天然产物药物湖南省工程研究中心,湖南 长沙 410011;

3. 新药组合生物合成国家地方联合工程研究中心,湖南 长沙 410011;

4. 天津中医药大学组分中药国家重点实验室,天津 301617

2. Hunan Engineering Research Center of Combinatorial Biosynthesis and Natural Product Drug Discovery, Changsha 410011, Hunan, China;

3. National Engineering Research Center of Combinatorial Biosynthesis for Drug Discovery, Changsha 410011, Hunan, China;

4. State Key Laboratory of Component-based Chinese Medicine, Tianjin University of Traditional Chinese Medicine, Tianjin 301617, China

Angucycline/angucyclinone类天然产物是从不同放线菌中分离出来的一类芳香聚酮化合物[1],主要由Ⅱ型聚酮合酶(Type Ⅱ polyketide synthase,Type Ⅱ PKS) 利用1个启动单元(乙酰辅酶A) 和9个延伸单元(丙二酰辅酶A) 来合成其分子骨架[2]。Angucycline和angucyclinone的区别在于母核上有无糖基连接,angucycline特指母核上有糖基取代的angucyclinone[3]。典型的angucycline/angucyclinone类化合物都包含1个角环蒽醌母核,譬如landomycins A (1)、B (2)、D (3)和E (4)[4-5]、urdamycins A (5) 和B (6)[6],以及hatomarubigins A (7) 和B (8)[7];非典型的此类化合物是指角环蒽醌中间体或被氧化的蒽醌环经过重排后形成的化合物,例如gilvocarcins M (9) 和V (10)[8]以及kinamycins A–C (11–13)[9]等。Angucycline/angucyclinone类天然产物具有广泛的生物活性,如抗菌、抗肿瘤、抗病毒、抗血小板聚集等,由于其独特的分子结构和良好的生物活性一直都是药物开发研究的重点之一,但因毒性较大或溶解度太低等问题未开发成为临床药物[2]。从产蓝链霉菌Streptomyces cyanogenus S-136中分离的化合物1[4]是目前这一家族中活性最好、最具发展前景的抗肿瘤药物先导物,其对许多癌细胞表现出的良好活性很可能与较长的糖链有关[2] (图 1)。

|

| 图 1 Angucycline/angucyclinone类代表化合物的化学结构(1–13) Fig. 1 Chemical structures of representative angucyclines/angucyclinones (1–13). |

| |

放线菌是活性天然产物的重要来源,全基因组测序进一步揭示了放线菌中存在丰富的天然产物生物合成基因簇(Biosynthetic gene clusters,BGCs)[10],平均每个菌株中大约有20–30个基因簇,但大多数次级代谢BGCs一般处于沉默状态[11-12]。通过改变培养条件、对调控基因或结构基因进行编辑、核糖体工程、基因组挖掘、活性导向的新产物发现,以及筛选来自特殊生态环境的放线菌和化学方法等策略可以发现新的angucycline/angucyclinone类化合物。在过去的几十年中,有一系列关于angucycline/angucyclinone类化合物的发现、生物合成、化学合成、生物活性等方面的综述性文章被发表。例如1988年Yang等发表了题为“苯并蒽醌类抗生素的研究进展”的综述文章[13];1992年,Rohr等发表了题为“Angucycline group antibiotics”的综述[1];1997年,Krohn等发表了题为“Angucyclines:Total syntheses,new structures,and biosynthetic studies of an emerging new class of antibiotics”的综述文章,总结了1991–1996年期间该类化合物的进展[14];2007年,Wang等发表题为“Angucycline/ Angucyclinone类抗生素的研究进展”的综述,对1996年6月后发现的angucycline/angucyclinone类化合物的结构和发现方法进行了详细总结[3];2012年,Kharel发表“Angucyclines: Biosynthesis,mode-of-action,new natural products,and synthesis”的综述,对1996–2010年期间这类化合物的发现、生物合成研究、化学合成、活性等方面的进展进行了系统总结[2]。在过去的10年中,随着基因组测序、生物信息学分析和合成生物学技术的快速发展,又有许多新的angucycline/angucyclinone类化合物被发现,但目前还没有对这些新发现化合物的结构、活性、发现策略等方面的系统阐述。针对这一现状,本综述从angucycline/ angucyclinone类化合物的发现策略着手,总结了2010–2020年期间关于这类化合物的结构和活性方面的研究进展。

1 基于OSMAC策略发现新型angucycline/ angucyclinone类化合物单菌株多次级代谢产物(One strain many compounds,OSMAC) 策略主要是通过改变发酵条件,如培养基成分和各种培养参数(温度、pH值、树脂和溶氧等),以及添加不同的刺激物或生物合成前体等来激活沉默基因簇以发现特定微生物菌株中的不同化合物[15-16]。该策略操作简单,无需对菌株的遗传背景有深入了解,在各类微生物天然产物的开发中得到了广泛应用,也是目前发现新型angucycline/angucyclinone类化合物的重要手段。

1.1 改变培养基成分或添加树脂通过改变培养基成分或者在已有发酵培养基中添加树脂可以增加angucycline/angucyclinone类天然产物的结构多样性。Guo等从健康稻蝗肠道来源的拟无枝酸菌Amycolatopsis sp. HCa1中分离到angucycline和tetrasaccharide类衍生物,随后又通过改变发酵培养基成分得到2个新化合物amycomycins A (14) 和B (15),其中14是角环被打开形成链状结构的angucyclinone类化合物[17]。Helaly等通过筛选对酸碱度具有不同耐受性的链霉菌,并对其在不同复杂培养基中的代谢物进行分析,从耐碱的链霉菌Acta 2930中分离得到warkmycin A (16),它不仅能够抑制革兰氏阳性菌的生长,对小鼠成纤维细胞NIH-3T3、人肝癌细胞HepG2以及人结肠癌细胞HT-29的半数抑制浓度(Half maximal inhibitory concentration,IC50)分别为2.74、1.26和1.61 µmol/L,也表现出较强的细胞毒性[18]。Abdelmohsen等通过对不同培养基中的代谢组学进行统计分析,确定了放线动孢菌属菌株Actinokineospora sp. EG49合成代谢物的最佳培养条件,并从中分离得到2个经过重排形成的新型angucycline类化合物actinosporins A (17) 和B (18),其中17对布鲁氏锥虫Trypanosoma brucei brucei的IC50值为15 µmol/L,这也是首次从放线动孢菌属菌株分离得到的angucycline类天然产物[19]。Ma等通过对比链霉菌CB01913在4种不同发酵培养基中次级代谢产物的丰富程度,选择1种进行扩大发酵,最终分离得到1个新型angucycline (19) 和11个新型angucyclinone (20–30) 类化合物,19和之前报道的TAN-1085[1]是仅有的2个在C-6上连接糖单元的angucycline类天然产物[20]。Qu等通过使用不同发酵培养基从海洋来源的链霉菌OC1610.4中分离得到vineomycins E (31) 和F (32),其中31含有1种罕见的脱氧糖,它对3种人乳腺癌细胞MCF-7 (IC50为6.07 µmol/L)、MDA-MB-231 (IC50为7.72 µmol/L) 和BT-474 (IC50为4.27 µmol/L) 均有较好的抑制作用;32含有独特的环裂解脱氧糖,但抗肿瘤活性较弱[21]。Wu等首先基于菌株的色素沉积从链霉菌QL37中分离到异于经典angucycline分子骨架的lugdunomycin (33),它包括1个七环、1个螺旋体、2个全碳立体中心和1个benzaza[4, 3, 3]螺桨烷主体,结构十分新颖[22]。随后他们又利用基于LC-MS/MS的分子网络方法筛选了该菌在77种不同培养基中产生的代谢产物,最终鉴别出9个新的、具有独特的环重排、氧化、还原和酰胺化的angucycline类天然产物(34–42)[22]。Bae等通过改变发酵培养基从海洋沉积物来源的链霉菌SUD119中分离得到C环经过重排的新型angucyclinone类化合物donghaecyclinones A–C (43–45),其中44对人肝癌细胞SK-HEP1 (IC50为9.6 µmol/L),45对人结肠癌细胞HCT-116 (IC50为8.0 µmol/L)、MDA-MB-231 (IC50为6.7 µmol/L)、人胃癌细胞SNU-638 (IC50为9.5 µmol/L)、人肺癌细胞A549 (IC50为9.6 µmol/L) 和SK-HEP1 (IC50为6.0 µmol/L) 均有较强的抑制作用,43对这些肿瘤细胞的抑制作用相对较弱[23]。Fang等通过在发酵培养基中添加HP20大孔树脂从棘孢小单孢菌Micromonospora echinospora SCSIO 04089中分离得到6个新型angucyclinone类化合物homophenanthroviridone (46)、homophenanthridonamide (47)、homostealthin D (48)、nenesfuran (49)、WS-5995 D (50) 和nenesophanol (51),其中46对人神经癌细胞SF-268 (IC50为5.4 µmol/L)、MCF-7 (IC50为6.8 µmol/L) 和HepG2 (IC50为1.4 µmol/L),47对HepG2 (IC50为4.0 µmol/L) 具有较好活性[24];此外46对耐甲氧西林金黄色葡萄球菌(Methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus,MRSA) shhs-A1、金黄色葡萄球菌ATCC 29213、苏云金芽孢杆菌SCSIO BT01、枯草芽孢杆菌1064以及溶壁微球菌SCSIO ML01的最低抑菌浓度(Minimum inhibitory concentration,MIC) 分别为2、2、4、4和4 µg/mL,均具有较强的抑制作用[24] (图 2)。

|

| 图 2 基于OSMAC策略发现的新型angucycline/angucyclinone类化合物(14–51) Fig. 2 Novel angucyclines/angucyclinones discovered via the OSMAC strategy (14–51). |

| |

在培养基中添加不同的化学诱导物或生物合成前体是一种非常简单和高效的用于改善或刺激微生物次生代谢的策略。为了发现新的次级代谢物并扩大“金属压力”策略的使用,Akhter等将不同的重金属离子应用于海洋来源的草生链霉菌Streptomyces pratensis NA-ZhouS1的发酵培养基中,通过添加100 µmol/L金属镍离子,分离得到2个在角环蒽醌核上连有水解糖单元的stremycins A (52) 和B (53),这是首次通过“金属压力应激技术”发现的新型angucycline类化合物,它们对铜绿假单胞菌CMCC (B) 10104、MRSA、肺炎克雷伯菌CMCC (B) 46117和大肠杆菌CMCC (B) 44102具有相同的抑菌活性,MIC值为16 µg/mL;而对枯草芽孢杆菌CMCC (B) 63501的MIC值为8–16 µg/mL[25]。Xu等通过在海绵来源稀有放线菌诺卡氏菌Nocardiopsis sp. HB-J378的培养基中添加LaCl3,从中分离得到nocardiopsistins A–C (54–56),它们对MRSA表现出不同的抑制作用,MIC值分别为12.5、3.12和12.5 µg/mL,其中55的活性与氯霉素相当[26]。Guo等通过在链霉菌KCB-132的生产培养基中添加LaCl3,从中分离得到具有氮杂环的对映异构体(±)-pratensilin D (57)、具有桥醚结构的kiamycin E (58)和A环裂解的pratensinon A (59),其中(+)-57和(–)-57对人肺癌细胞NCI-H460 (IC50分别为9.4和4.9 µg/mL)、(–)-57对HepG2 (IC50为9.3 µg/mL) 以及59对结肠癌细胞Colon38 (IC50为7.3 µg/mL) 和人宫颈癌细胞Hela (IC50为10.3 µg/mL) 具有较强细胞毒性;另外(–)-57对蜡样芽孢杆菌(MIC为4 µg/mL) 具有较强的抑制作用[27]。

Fan等通过在委内瑞拉链霉菌Streptomyces venezuelae ISP5230发酵培养基中添加不同的非天然氨基酸分离得到6个新型angucycline类化合物jadomycins Abu (60)、Nle (61)、Hse (62)、K (63)、Orn (64) 和Daba (65),其中60、61和64对MCF-7 (IC50分别为2.7、8.3和3 µmol/L)、HCT-116 (IC50分别为8.5、14.5和9.2 µmol/L) 以及人微血管内皮细胞HMEC (IC50分别为4.5、5.4和10.2 µmol/L)均具有较好的抑制作用[28]。Forget等采用类似的策略,通过在培养基中添加关键前体Nε-三氟乙酰-L-赖氨酸,从委内瑞拉链霉菌ISP5230中首次分离得到3个含有酰胺和呋喃环的新型angucycline类化合物(66–68),它们对耐万古霉素肠球菌和MRSA具有一定的活性[29]。Tata等通过在链霉菌PAL114的M2合成培养基中添加前体L-色氨酸,从中分离得到2个含有L-色氨酸和糖苷衍生物发色团的蓝紫色化合物mzabimycins A (69) 和B (70),它们对藤黄微球菌ATCC 9314和单核细胞增生性李斯特氏菌ATCC 13932具有一定活性[30] (图 3)。

|

| 图 3 基于OSMAC策略发现的新型angucycline/angucyclinone类化合物(52–70) Fig. 3 Novel angucyclines/angucyclinones discovered via the OSMAC strategy (52–70). |

| |

基因改造主要是对微生物中的基因进行包括异源表达、敲除和过表达[31]或者核糖体工程等操作[32],常用来研究微生物天然产物的生物合成以及发掘新天然产物。近年来许多具有新颖结构的angucycline/angucyclinone类天然产物通过这种方法被发现。

2.1 异源表达Izawa等将链霉菌2238-SVT4中负责hatomarubigins类化合物合成的25个基因在变铅青链霉菌Streptomyces lividans TK23中进行异源表达,并将编码亚甲基桥形成酶的hrbF基因进行缺失,从中分离得到1个该家族的新成员hatomarubigin F (71)[33]。Yang等将小单孢球链藻菌Micromonospora rosaria SCSIO N160中的fluostatins基因簇在天蓝色链霉菌Streptomyces coelicolor YF11中异源表达,在添加3% (W/V) 海盐的条件下产生了fluostatin L (72) 和difluostatin A (73),其中73是通过C-1和C-5′耦合形成的罕见的不对称二聚体,对肺炎克雷伯菌ATCC 13883 (MIC为4 µg/mL)、嗜水气单胞菌ATCC 7966 (MIC为4 µg/mL) 和金黄色葡萄球菌ATCC 29213 (MIC为8 µg/mL) 表现出较好抗菌活性[34]。Schäfer等首先在天蓝色链霉菌M1152中异源表达simocyclinones的BGC,然后通过在该系统中缺失与angucyclinone相关的酮还原基因simC7分离得到含有四烯结构的7-oxo-simocyclinone D8 (74),其对DNA解旋酶具有一定的抑制作用[35]。Bilyk等通过在白色链霉菌Streptomyces albus J1074中异源表达grecocyclines的BGC,产生了3个具有独特结构的化合物grecocyclines A–C (75–77),它们结构中均包含双糖侧链,并且在C-5位置连有氨基糖和硫醇基团[36]。同年Myronovskyi等将landomycins基因簇中的调控基因lanI和lanK在白色链霉菌J1074中异源表达,分离得到11-hydroxyrabelomycin (78)、6, 11-dihydroxytetrangulol (79)、fridamycins F (80)和G (81),其中78和79对革兰氏阳性细菌如枯草芽孢杆菌DSM 1092和藤黄微球菌DSM 20030具有较好的活性,MIC值均在1 µg/mL左右,而81对金黄色葡萄球菌Newman (MIC为1 µg/mL) 表现出较强的选择性抑制作用[37]。另外,Fidan等通过在变铅青链霉菌K4中异源表达链霉菌SCC-2136中的C-糖基转移酶基因schS7得到1个新的angucycline化合物GG31 (82)[38] (图 4)。

|

| 图 4 基于基因改造发现的新型angucycline/angucyclinone类化合物(71–91) Fig. 4 Novel angucyclines/angucyclinones discovered via the genetic modification strategy (71–91). |

| |

Forget等通过缺失jadomycin脱氧糖生物合成途径中的4, 6-脱水酶基因jadT,产生了新型angucycline类化合物jadomycin DS (83)[39]。Huang等采用同样方法,通过缺失小单孢球链藻菌SCSIO N160的fluostatins基因簇中编码酰胺转移酶的基因flsN3,分离得到4个新型angucycline类化合物stealthins D–G (84–87)[40]。Fidan等通过缺失链霉菌SCC-2136中的糖基转移酶基因schS9,发现1个新的angucycline化合物OZK1 (88)[38]。

利用过表达途径特异性调控因子来激活沉默基因簇是一种较为常用的策略,Zhou等为了激活恰塔努加链霉菌Streptomyces chattanoogensis L10中沉默的angucycline类BGC,通过过表达与jadomycin基因簇中的正调控因子jadR1具有高度同源性的途径特异性调控基因chaI,成功获得了chattamycins A (89) 和B (90),其中89对MCF-7(IC50为6.46 µmol/L)、90对MCF-7 (IC50为1.08 µmol/L) 和HepG2 (IC50为5.93 µmol/L) 表现出较好的抑制活性[41] (图 4)。

2.3 核糖体工程核糖体工程是一种简单易行的激活沉默BGCs的方法。为了研究恰塔努加链霉菌L10中其他沉默基因簇的代谢产物,Li等使用核糖体工程技术对编码核糖体蛋白S12的rpsL或编码RNA聚合酶β亚甲基的rpoB的高度保守区域进行定点突变,产生了10个突变株[42]。其中突变菌株L10/RpoB (H437Y) 可以在平板上沉积色素,基于此,Li等对该突变株进行研究并从中分离得到anthrachamycin (91),但其基本没有抗菌和抗肿瘤活性;在ABTS自由基清除实验和FRAP铁离子还原实验中,其抗氧化活性分别为67.28和24.31 mg VCE/g LP[42] (图 4)。

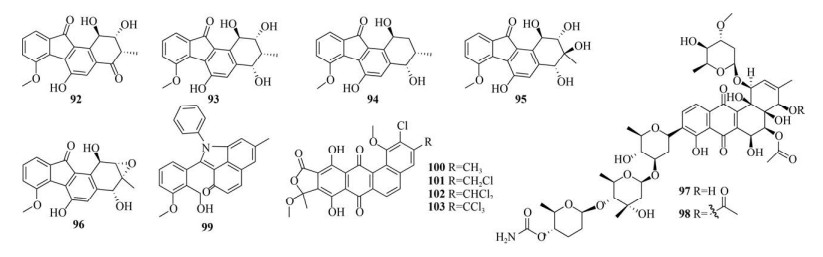

3 基于基因组挖掘发现新型angucycline/ angucyclinone类化合物随着高通量测序技术的快速发展,基因组挖掘在开发微生物天然产物的研究中被广为应用,并成为一种发现特定类型新化合物的高效策略[43-44]。Jin等以Ⅱ型聚酮合成酶KSα和KSβ的保守序列为分子探针从链霉菌PKU-MA00045中分离得到具有独特的6-5-6-6环骨架的fluostatins M–Q (92–96)[45]。由于许多天然产物的糖基部分通常参与细胞靶点的相互作用和分子识别,Malmierca等以2类6-脱氧糖合成基因为探针筛选从切叶蚂蚁表皮分离的70株链霉菌,最终成功地从链霉菌CS057中分离得到2个新型angucycline类化合物warkmycins CS1 (97) 和CS2 (98)[46]。Yang等通过靶向Ⅱ型聚酮合酶找到链霉菌PKU-MA00218[47],然后Liu等从中分离得到1个具有苯胺结构的新型angucyclinone类化合物(99)[48]。Cruz等采用PCR方法以放线异壁酸菌Actinoallomurus的保守序列为分子探针筛选收集的放线异壁酸菌,最终从放线异壁酸菌ID145698中分离得到4个具有不同寻常内酯环和氯原子取代的新型angucyclinone类化合物allocyclinones A–D (100–103),其中101–103对金黄色葡萄球菌ATCC 6538P (MIC分别为2、1和0.25 μg/mL),100、102和103对酿脓链球菌L49 (MIC分别为4、2和0.25 μg/mL),102和103对粪肠球菌L560 (MIC分别为1 μg/mL和0.5 μg/mL) 以及103对屎肠球菌L569 (MIC为4 μg/mL) 具有较强抗菌活性,随着氯原子取代的数量增加,抗菌活性也随之增加[49]。由上可知,通过靶向高度保守的angucycline/angucyclinone类BGCs和一些编码特定修饰酶的基因,可以高效地获得含有预期结构修饰的这类化合物(图 5)。

|

| 图 5 基于基因组挖掘发现的新型angucycline/angucyclinone类化合物(92–103) Fig. 5 Novel angucyclines/angucyclinones discovered via the genome mining strategy (92–103). |

| |

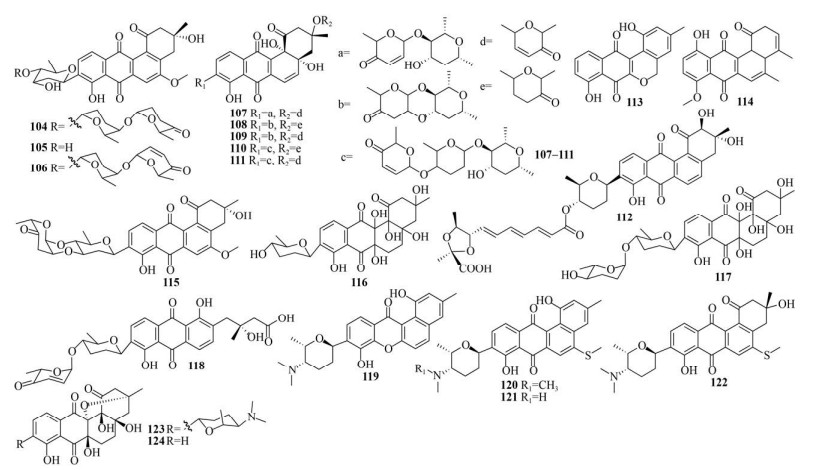

活性导向筛选是发现新型天然产物的一种非常经典的方法,目前仍被广泛应用于angucycline/ angucyclinone类天然产物的开发中。Ren等基于对人结肠癌细胞SW620的抑制活性筛选,从链霉菌N05WA963中分离得到N05WA963s A (104)、B (105) 和D (106),这3个化合物对SW620 (IC50分别为4.4、7.1和1.0 µmol/L)、食管癌细胞YES-4 (IC50分别为7.9、8.5和4.0 µmol/L) 和人脑神经胶质瘤细胞U251SP (IC50分别为5.6、10.3和3.3 µmol/L),106对人白血病细胞K-562 (IC50为1.5 µmol/L),104和106对MDA-MB-231 (IC50分别为9.8和2.8 µmol/L) 和人脑神经胶质瘤细胞T-98 (IC50分别为5.3和3.1 µmol/L) 具有较好抗肿瘤活性[50]。基于对寄生水霉Saprolegnia parasitica的抑制活性筛选,Nakagawa等从链霉菌TK08046分离得到5个新型angucycline化合物saprolmycins A–E (107–111),它们对寄生水霉(MIC分别为0.003 9、8、1、1和0.007 8 µg/mL)均具有较好的活性,其中111对枯草芽孢杆菌的MIC为7.8 µg/mL,对水蚤Daphnia pulex的半数致死剂量(Median lethal dose,LD50) 为4.5 µg/mL,也有较好抑制作用[51]。WalK (组氨酸激酶)/WalR (反应调节器) 双组分信号传导系统是一类新型革兰氏阳性菌的抗菌药物靶点,Igarashi等通过筛选靶向组氨酸激酶WalK的抑制剂,从链霉菌MK844-mF10中分离到waldiomycin (112),它对金黄色葡萄球菌Smith和枯草芽孢杆菌具有较好的抑制作用,MIC值均为8 µg/mL[52]。随后的研究也证明112通过抑制WalK的活性来降低walR调控基因的表达,从而影响细胞壁代谢和细胞分裂[53]。Mullowney等基于对人卵巢癌细胞NCI-60 SKOV3的体外活性筛选,从源自越南东海猫坝半岛沉积物的小单孢菌中分离到lagumycin B (113),其对小鼠卵巢表面上皮细胞MOSE以及小鼠输卵管上皮细胞MOE的半数致死浓度(Median lethal concentration,LC50) 分别为9.80 µmol/L和10.8 µmol/L,表现出较好的细胞毒性[54]。为了评价流苏羽叶楸茎皮对11种病原菌的抑菌潜力,Awang等基于对MRSA的活性筛选,从流苏羽叶楸茎皮的分离菌中得到1个新型angucycline化合物C1 (114),它对表皮葡萄球菌ATCC 12228 (MIC为3.13 mg/mL)、MRSA (MIC为6.25 mg/mL) 和金黄色葡萄球菌ATCC 25923 (MIC为6.25 mg/mL)均具有较好的抗菌作用[55]。Bao等基于对金黄色葡萄球菌的活性筛选,从链霉菌XZHG99T中分离得到1个新的angucycline类化合物grincamycin M (115),其对A549 (IC50为3.10 µmol/L)、人肺癌细胞H157 (IC50为2.82 µmol/L)、MCF-7 (IC50为2.81 µmol/L)、MDA-MB-231 (IC50为2.14 µmol/L) 和HepG2 (IC50为9.12 µmol/L) 均表现出较好的细胞毒性[56]。Voitsekhovskaia等基于对枯草芽孢杆菌的抗菌活性筛选,从源自贝加尔湖特有软体动物的链霉菌IB201691-2A中分离得到3个新型angucycline类化合物baikalomycins A–C (116–118),其中116的糖基为β-D-amicetose并且在C-6a和C-12a位有2个额外的羟基,而117和118分别有α-L-amicetose和α-L-aculose为第二糖基[57]。生物活性研究表明116和117对A549和MCF-7有一定的活性,而118对人肝癌细胞Huh7.5 (IC50为7.62 µmol/L) 和SW620 (IC50为3.87 µmol/L) 表现出良好的活性[57]。Chang等结合HPLC-UV图谱和对人慢性髓系白血病细胞K562的细胞毒性,从海洋沉积源链霉菌HDN15129中发现了6个化合物monacycliones G–K (119–123) 和ent-gephyromycin A (124),其中119具有独特的以黄酮为核心与氨基脱氧糖相连的骨架结构,120–122是带有S-甲基的罕见angucycline类天然产物;119对急性粒细胞白血病细胞HL-60 (IC50为3.5 µmol/L)、K562 (IC50为7.1 µmol/L) 和人神经母细胞瘤细胞SH-SY5Y (IC50为4.3 µmol/L) 等多种人类肿瘤细胞均表现出较强的细胞毒性[58] (图 6)。

|

| 图 6 基于活性导向发现的新型angucycline/angucyclinone类化合物(104–124) Fig. 6 Novel angucyclines/angucyclinones discovered via the bioactivity-guided isolation strategy (104–124). |

| |

深海具有高压、低温和寡营养等多种极端环境,因此来自深海的链霉菌被认为是开发新型天然产物的重要微生物资源[59]。近年来从海底沉积物、海绵和红树林等样品中分离得到的海洋链霉菌吸引了研究者的极大关注,从中发现了很多新型angucycline/angucyclinone类化合物[60]。Huang等从南海沉积物来源的卢西塔链霉菌SCSIO LR32中分离得到4个新型angucycline化合物grincamycins B–D (125–127) 和F (128),其中125和127对小鼠黑色素瘤细胞B16 (IC50分别为2.1和5.4 µmol/L) 和HepG2 (IC50分别为8.5和9.7 µmol/L)、125对HeLa (IC50为6.4 µmol/L) 以及127对MCF-7 (IC50为6.1 µmol/L) 具有较好活性[61]。Lai等同样从链霉菌SCSIO LR32中分离鉴定出3个新型angucycline类化合物grincamycins I–K (129–131),其中130对人乳腺癌细胞MDA-MB-435 (IC50为2.63 µmol/L)、MDA-MB-231 (IC50为4.68 µmol/L)、NCI-H460 (IC50为5.40 µmol/L)、HCT-116 (IC50为2.63 µmol/L) 和HepG2 (IC50为4.80 µmol/L) 均显示出较强的抗肿瘤活性,但其对人类正常乳腺上皮细胞MCF10A (IC50为2.43 µmol/L) 也表现出较强的细胞毒性[62]。Xie等从深海沉积物来源的灰色链霉菌Streptomyces griseus M268中分离得到kiamycin (132),其对HL-60、A549和人肝癌细胞BEL-7402具有一定抑制作用[63]。Song等从深海沉积物来源的链霉菌SCSIO 11594中分离鉴定出2个新型angucycline类化合物marangucyclines A (133) 和B (134),其中134对A549 (IC50为0.45 µmol/L)、人鼻咽癌细胞CNE2 (IC50为0.56 µmol/L)、HepG2 (IC50为0.24 µmol/L) 和MCF-7 (IC50为0.43 µmol/L) 等抗肿瘤活性优于阳性对照顺铂,其对正常肝细胞HL-7702的IC50值为3.67 µmol/L[64]。Hu等从中国台湾海峡沉积物来源的海洋链霉菌A6H中分离得到vineolactone A (135) 和vineomycinone B2苄酯(136),但这2个化合物未表现出明显的抗菌和抗肿瘤活性[65]。Xie等从海洋沉积物来源的灰色链霉菌M268中分离得到具有独特醚桥结构的新型angucyclinone化合物grisemycin (137),其对HL-60具有一定抗肿瘤活性[66]。Guo等从灰色链霉菌M268中分离得到具有桥醚结构的kiamycins B (138) 和C (139) 以及结构相关衍生物(140),其中140对人肺腺癌细胞NCI-H1975的IC50值为17.8 µg/mL[67]。Zhou等从海洋沉积物来源的链霉菌HN-A124分离得到罕见的C-3和C-12a形成环氧结构的gephyyamycin (141) 以及具有乙酰半胱氨酸基团的cysrabelomycin (142),其中142对人卵巢细胞A2780 (IC50为10.23 µmol/L)具有较好活性,对金黄色葡萄球菌和白色念珠菌具有一定抑制作用[68]。Yixizhuoma等从海洋链霉菌IFM 11490中分离到6个新型angucycline类化合物elmenols C–H (143–148),其中147和148与凋亡相关的肿瘤坏死因子配体联合使用对人胃腺癌细胞显示出较好活性[69]。Ma等从深海沉积物来源的链霉菌PKU-MA01297分离得到2个首次报道的具有1-O-β-D-吡喃葡萄糖基的angucycline类化合物(149)和(150),它们具有一定抗菌活性[70]。Zhang等从海洋沉积物来源草生链霉菌KCB-132中分离得到化合物(±)-pratenone A (151) 和furamycins Ⅰ–Ⅲ (152–154),其中151对金黄色葡萄球菌CMCC 26003 (MIC为8 μg/mL) 表现出较好抑制作用,154对人类乳腺癌细胞PANC-1和HepG2表现出一定活性[71]。Gui等从红树林沉积物来源的淀粉酶链霉菌Streptomyces diastaticus SCSIO GJ056中分离到9个新型angucycline类化合物urdamycins N1–N9 (155–163),161和162是首次发现的天然存在的(5R, 6R)-angucycline糖苷类化合物,分别为159和163的非对映体[72]。Yang等同样从深海来源卢西塔链霉菌OUCT16-27分离到1个化合物grincamycin L1 (164),其对粪肠球菌CCARM 5172 (MIC为6.25 μg/mL)、屎肠球菌CCARM 5203 (MIC为3.12 μg/mL) 和金黄色葡萄球菌CCARM 3090 (MIC为6.25 μg/mL) 均有较好的生长抑制作用[59]。

海洋中包含多种复杂的生态系统,如潮间带生态系统与海底生态系统有很大不同,定期的潮汐浸泡会导致更多的有机碳以及氧气和硫酸盐溶解到潮间带沉积物中,这有利于微生物的生存,尤其是好氧的链霉菌[73]。Peng等从威海小石岛潮间带沉积物中分离到链霉菌OC1610.4,并从中分离了2个新型angucycline类化合物landomycin N (165) 和vineomycin D (166),其中166具有重排形成的线性三环母核结构,并且在母核侧链包含2种糖基[73]。此外,海绵中含有的包括链霉菌在内的多种微生物,是良好的新型天然产物的来源[74]。Vicente等从源自加勒比地区海绵的链霉菌M7_15中分离到6个新的C-氨基糖的化合物monacyclinones A–F (167–172),其中172是通过2个独特的环氧环连接到angucyclinone的部分,再由1个角氧键和1个附加的氨基脱氧糖相连[75]。相对于同时分离到的其他同系物,172对横纹肌肉瘤癌细胞SJCRH30的半数有效浓度(Median effective concentration,EC50) 为0.73 µmol/L,表现出最强的抑制活性,这表明额外的氨基脱氧糖亚基部分可能对这类分子的抗肿瘤生物活性很重要[75]。上述研究揭示了源自各种极端环境或未开发生态系统中的海洋链霉菌在新型angucycline/ angucyclinone类化合物发现中的巨大潜能(图 7)。

|

| 图 7 从特殊环境来源放线菌发现的新型angucycline/angucyclinone类化合物(125–172) Fig. 7 Novel angucyclines/angucyclinones discovered from actinomycetes from underexplored environments (125–172). |

| |

Guo等从健康稻蝗肠道中的细菌HCa1中分离得到(2R, 3R)-2-hydroxy-8-O-methyl tetrangomycin (173) 和(2R, 3R)-2-hydroxy-5-O-methyltetrangomycin (174),其中174对人胃腺癌细胞SGC-7901具有一定活性[76]。Shaaban等从阿巴拉契亚山脉洞穴附近样本来源的链霉菌KY40-1分离得到saquayamycins G–K (175–179),其中176和177结构中具有不同寻常的氨基糖,这是首次从angucycline类天然产物中发现这类结构[77]。175–179对人前列腺癌细胞PC3 (IC50分别为0.55、0.79、0.91、0.18和0.15 µmol/L) 和非小细胞肺癌H460 (IC50分别为6.72、3.30、7.94、5.69和7.28 µmol/L) 表现出较好的抗肿瘤活性[77]。Boonlarppradab等从稀有放线菌糖多孢菌Saccharoployspora sp. BCC 21906分离得到3个新型angucyclinone类化合物saccharosporones A–C (180–182),其中180对非恶性肿瘤细胞Vero (IC50为9.1 µmol/L),181和182对人口腔表皮样癌细胞VB (IC50分别为9.1 µmol/L和4.9 µmol/L)、MCF-7 (IC50分别为3.4 µmol/L和3.6 µmol/L) 和人视网膜母细胞瘤细胞NCI-H187 (IC50分别为7.7 µmol/L和4.5 µmol/L) 表现出较好抗肿瘤活性[78]。Rabia-Boukhalfa等从撒哈拉沙漠盐土样品来源的卤代耐受性诺卡氏菌HR-4中分离得到(–)-7-deoxy-8-O-methyltetrangomycin (183),其对金黄色葡萄球菌ATCC 25923和ATCC 43300具有一定抑菌活性[79] (图 8)。

|

| 图 8 从特殊环境来源放线菌或稀有放线菌中发现的新型angucycline/angucyclinone类化合物(173–183) Fig. 8 Novel angucyclines/angucyclinones discovered from actinomycetes from underexplored environments or rare actinomycetes (173–183). |

| |

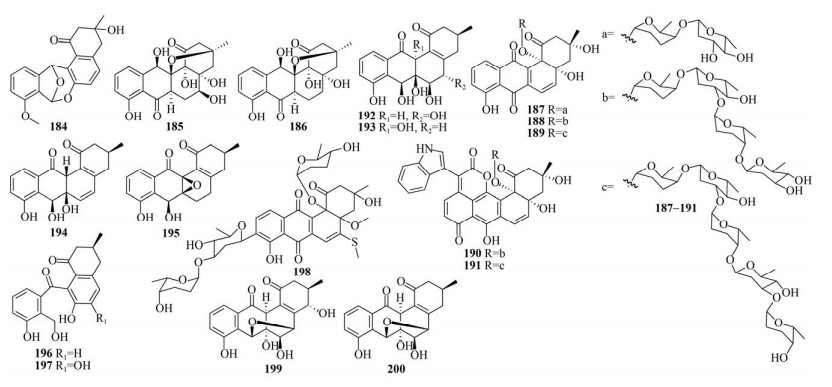

Chen等通过LC-DAD-MS分析方法从链霉菌LS1924分离得到1个环扩张的angucyclinone类化合物LS1924A (184),其对HepG2和A549具有一定活性[80]。Jiang等通过对链霉菌SS13I进行化学研究从中分离得到2个桥接类型的angucyclinone类化合物gephyromycins B (185) 和C (186),其中186对PC3具有较强细胞毒性,IC50值为1.38 µmol/L[81]。Kalyon等使用高效液相二极管阵列方法筛选从马来西亚分离的100株放线菌,最终从链霉菌Acta 3034中分离得到langkocyclines A1–A3 (187–189)、B1 (190) 和B2 (191),其中188和189对枯草芽孢杆菌(IC50分别为4.07 µmol/L和2.17 µmol/L),189对HepG2 (IC50为2.5–5.0 µmol/L) 和小鼠胚胎细胞NIH 3T3 (IC50为2.5–5.0 µmol/L) 表现出较好活性[82]。Wang等通过HPLC-DAD方法筛选其实验室的放线菌,最终从链霉菌KIB-M10分离得到cangumycins A–F (192–197),其中193和196对抗CD3/抗CD28抗体激活的人类T细胞表现出较强活性,IC50值分别为8.1 µmol/L和2.7 µmol/L [83]。Dan等在基因组分析和全局天然产物分子网络方法指导下从链霉菌OA293中分离出urdamycin V (198),其活性较弱[84]。Kim等基于分子网络的MS/MS方法从栀子花根部分离的链霉菌GJA1中得到2个新的桥接C-5和C-7的angucyclinone类化合物gardenomycins A (199) 和B (200)[85] (图 9)。

|

| 图 9 利用化学方法发现的新型angucycline/angucyclinone类化合物(184–200) Fig. 9 Novel angucyclines/angucyclinones discovered using chemical methods (184–200). |

| |

随着大规模放线菌菌种库的建立[86]、微生物基因组测序及生物信息学技术[87-88]的广泛应用,以及各种高通量筛选[89]、基因组挖掘[90-91]和新的化合物鉴定技术[92]的快速发展,当前微生物天然产物的发现策略与传统的方法相比更为特异和高效[93]。由于海洋来源的放线菌与土壤中放线菌的生存环境存在较大差异,是近年来发现新型化合物的重要来源。Angucycline/angucyclinone类天然产物最早于20世纪60年代被发现,因其多样的化学结构和新颖的生物活性一直是生物合成和有机合成领域的热点分子。近年来随着新菌种资源的获得和新发现策略的不断开发,不断有结构新颖、活性较好的新分子涌现,丰富着angucycline/ angucyclinone类天然产物的结构多样性。本文总结了近10年来(2010–2020年) 通过不同策略发现的angucycline/angucyclinone类天然产物。同时,通过对它们的生物活性研究可以发现,修饰基团的位置和数量都会对活性产生较大影响。利用组合生物合成方法对糖基转移酶[38]、FAD依赖型单氧合酶和开环氧化酶[94]、碳-碳键环裂解氧合酶[95]以及酰胺氧化酶[40]等后修饰酶进行敲除、过表达、异源表达、点突变等操作,可以开发出具有新结构、新活性的angucycline/angucyclinone类天然产物。另外,通过对关键合成酶或修饰酶的作用机理的研究,以及angucycline/angucyclinone类化合物的构效关系研究等,结合基因编辑、药物设计、靶点预测等技术,将有助于通过合成生物学的方法发现具有独特分子结构或具有新作用机制的化合物,促进angucycline/angucyclinone类天然产物的临床开发。本文中提到的发现新化合物的方法也适用于其他类型的微生物天然产物的发现,为发现具有不同结构特征的新天然产物提供了很好的借鉴。

| [1] |

Rohr J, Thiericke R. Angucycline group antibiotics. Nat Prod Rep, 1992, 9(2): 103-137. DOI:10.1039/np9920900103

|

| [2] |

Kharel MK, Pahari P, Shepherd MD, et al. Angucyclines: biosynthesis, mode-of-action, new natural products, and synthesis. Nat Prod Rep, 2012, 29(2): 264-325. DOI:10.1039/C1NP00068C

|

| [3] |

汪月, 韩宁宁, 孙承航. Angucycline/Angucyclinone类抗生素的研究进展. 国外医药(抗生素分册), 2007, 28(3): 97-102. Wang Y, Han NN, Sun CH. Advance in new angucycline/angucyclinone antibiotic discoveries. World Notes Antibiot, 2007, 28(3): 97-102 (in Chinese). DOI:10.3969/j.issn.1001-8751.2007.03.001 |

| [4] |

Henkel T, Rohr J, Beale JM, et al. Landomycins, new angucycline antibiotics from Streptomyces sp. Ⅰ. Structural studies on landomycins A–D. J Antibiot (Tokyo), 1990, 43(5): 492-503. DOI:10.7164/antibiotics.43.492

|

| [5] |

Li XH, Woodward J, Hourani A, et al. Synthesis of the 2-deoxy trisaccharide glycal of antitumor antibiotics landomycins A and E. Carbohydr Res, 2016, 430: 54-58. DOI:10.1016/j.carres.2016.04.031

|

| [6] |

Rohr J, Beale JM, Floss HG. Urdamycins, new angucycline antibiotics from Streptomyces fradiae. Ⅳ. Biosynthetic studies of urdamycins A–D. J Antibiot (Tokyo), 1989, 42(7): 1151-1157. DOI:10.7164/antibiotics.42.1151

|

| [7] |

Hayakawa Y, Ha SC, Kim YJ, et al. Studies on the isotetracenone antibiotics. Ⅳ. Hatomarubigins A, B, C and D, new isotetracenone antibiotics effective against multidrug-resistant tumor cells. J Antibiot (Tokyo), 1991, 44(11): 1179-1186. DOI:10.7164/antibiotics.44.1179

|

| [8] |

Balitz DM, O'Herron FA, Bush J, et al. Antitumor agents from Streptomyces anandii: gilvocarcins V, M and E. J Antibiot (Tokyo), 1981, 34(12): 1544-1555. DOI:10.7164/antibiotics.34.1544

|

| [9] |

Omura S, Nakagawa A, Yamada H, et al. Structures and biological properties of kinamycin A, B, C, and D. Chem Pharm Bull (Tokyo), 1973, 21(5): 931-940. DOI:10.1248/cpb.21.931

|

| [10] |

Bentley SD, Chater KF, Cerdeño-Tárraga AM, et al. Complete genome sequence of the model actinomycete Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2). Nature, 2002, 417(6885): 141-147. DOI:10.1038/417141a

|

| [11] |

Jakubiec-Krzesniak K, Rajnisz-Mateusiak A, Guspiel A, et al. Secondary metabolites of actinomycetes and their antibacterial, antifungal and antiviral properties. Pol J Microbiol, 2018, 67(3): 259-272. DOI:10.21307/pjm-2018-048

|

| [12] |

Reen FJ, Romano S, Dobson ADW, et al. The sound of silence: activating silent biosynthetic gene clusters in marine microorganisms. Mar Drugs, 2015, 13(8): 4754-4783. DOI:10.3390/md13084754

|

| [13] |

杨建新. 苯并蒽醌类抗生素的研究进展. 国外医药(抗生素分册), 1988, 9(2): 98-109. |

| [14] |

Krohn K, Rohr J. Angucyclines: total syntheses, new structures, and biosynthetic studies of an emerging new class of antibiotics. Top Curr Chem, 1997(188): 127-195.

|

| [15] |

Bode HB, Bethe B, Höfs R, et al. Big effects from small changes: possible ways to explore nature's chemical diversity. Chem Bio Chem, 2002, 3(7): 619-627. DOI:10.1002/1439-7633(20020703)3:7<619::AID-CBIC619>3.0.CO;2-9

|

| [16] |

Liu MM, Grkovic T, Liu XT, et al. A systems approach using OSMAC, Log P and NMR fingerprinting: an approach to novelty. Synth Syst Biotechnol, 2017, 2(4): 276-286. DOI:10.1016/j.synbio.2017.10.001

|

| [17] |

Guo ZK, Liu SB, Jiao RH, et al. Angucyclines from an insect-derived actinobacterium Amycolatopsis sp. HCa1 and their cytotoxic activity. Bioorg Med Chem Lett, 2012, 22(24): 7490-7493. DOI:10.1016/j.bmcl.2012.10.048

|

| [18] |

Helaly SE, Goodfellow M, Zinecker H, et al. Warkmycin, a novel angucycline antibiotic produced by Streptomyces sp. Acta 2930. J Antibiot (Tokyo), 2013, 66(11): 669-674. DOI:10.1038/ja.2013.74

|

| [19] |

Abdelmohsen U, Cheng C, Viegelmann C, et al. Dereplication strategies for targeted isolation of new antitrypanosomal actinosporins A and B from a marine sponge associated-actinokineospora sp. EG49. Mar Drugs, 2014, 12(3): 1220-1244. DOI:10.3390/md12031220

|

| [20] |

Ma M, Rateb ME, Teng QH, et al. Angucyclines and angucyclinones from Streptomyces sp. CB01913 featuring C-ring cleavage and expansion. J Nat Prod, 2015, 78(10): 2471-2480. DOI:10.1021/acs.jnatprod.5b00601

|

| [21] |

Qu XY, Ren JW, Peng AH, et al. Cytotoxic, anti-migration, and anti-invasion activities on breast cancer cells of angucycline glycosides isolated from a marine-derived Streptomyces sp. Mar Drugs, 2019, 17(5): 277. DOI:10.3390/md17050277

|

| [22] |

Wu CS, Van Der Heul HU, Melnik AV, et al. Lugdunomycin, an angucycline-derived molecule with unprecedented chemical architecture. Angew Chem, 2019, 131(9): 2835-2840. DOI:10.1002/ange.201814581

|

| [23] |

Bae M, An JS, Hong SH, et al. Donghaecyclinones A–C: new cytotoxic rearranged angucyclinones from a volcanic island-derived marine Streptomyces sp. Mar Drugs, 2020, 18(2): 121. DOI:10.3390/md18020121

|

| [24] |

Fang ZJ, Jiang XD, Zhang QB, et al. S-bridged thioether and structure-diversified angucyclinone derivatives from the South China sea-derived Micromonospora echinospora SCSIO 04089. J Nat Prod, 2020, 83(10): 3122-3130. DOI:10.1021/acs.jnatprod.0c00719

|

| [25] |

Akhter N, Liu YQ, Auckloo BN, et al. Stress-driven discovery of new angucycline-type antibiotics from a marine Streptomyces pratensis NA-ZhouS1. Mar Drugs, 2018, 16(9): 331. DOI:10.3390/md16090331

|

| [26] |

Xu DB, Nepal KK, Chen J, et al. Nocardiopsistins A–C: new angucyclines with anti-MRSA activity isolated from a marine sponge-derived Nocardiopsis sp. HB-J378. Synth Syst Biotechnol, 2018, 3(4): 246-251. DOI:10.1016/j.synbio.2018.10.008

|

| [27] |

Guo L, Zhang L, Yang QL, et al. Antibacterial and cytotoxic bridged and ring cleavage angucyclinones from a marine Streptomyces sp. Front Chem, 2020, 8: 586. DOI:10.3389/fchem.2020.00586

|

| [28] |

Fan KQ, Zhang X, Liu HC, et al. Evaluation of the cytotoxic activity of new jadomycin derivatives reveals the potential to improve its selectivity against tumor cells. J Antibiot (Tokyo), 2012, 65(9): 449-452. DOI:10.1038/ja.2012.48

|

| [29] |

Forget SM, Robertson AW, Overy DP, et al. Furan and lactam jadomycin biosynthetic congeners isolated from Streptomyces venezuelae ISP5230 cultured with Nε-trifluoroacetyl-L-lysine. J Nat Prod, 2017, 80(6): 1860-1866. DOI:10.1021/acs.jnatprod.7b00152

|

| [30] |

Tata S, Aouiche A, Bijani C, et al. Mzabimycins A and B, novel intracellular angucycline antibiotics produced by Streptomyces sp. PAL114 in synthetic medium containing L-tryptophan. Saudi Pharmaceut J, 2019, 27(7): 907-913. DOI:10.1016/j.jsps.2019.06.004

|

| [31] |

Sinha R, Sharma B, Dangi AK, et al. Recent metabolomics and gene editing approaches for synthesis of microbial secondary metabolites for drug discovery and development. World J Microbiol Biotechnol, 2019, 35(11): 166. DOI:10.1007/s11274-019-2746-2

|

| [32] |

Ochi K, Okamoto S, Tozawa Y, et al. Ribosome engineering and secondary metabolite production. Adv Appl Microbiol, 2004, 56: 155-184.

|

| [33] |

Izawa M, Kimata S, Maeda A, et al. Functional analysis of hatomarubigin biosynthesis genes and production of a new hatomarubigin using a heterologous expression system. J Antibiot (Tokyo), 2013, 67(2): 159-162.

|

| [34] |

Yang CF, Huang CS, Zhang WJ, et al. Heterologous expression of fluostatin gene cluster leads to a bioactive heterodimer. Org Lett, 2015, 17(21): 5324-5327. DOI:10.1021/acs.orglett.5b02683

|

| [35] |

Schäfer M, Le TBK, Hearnshaw SJ, et al. SimC7 is a novel NAD(P)H-dependent ketoreductase essential for the antibiotic activity of the DNA gyrase inhibitor simocyclinone. J Mol Biol, 2015, 427(12): 2192-2204. DOI:10.1016/j.jmb.2015.03.019

|

| [36] |

Bilyk O, Sekurova ON, Zotchev SB, et al. Cloning and heterologous expression of the grecocycline biosynthetic gene cluster. PLoS ONE, 2016, 11(7): e0158682. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0158682

|

| [37] |

Myronovskyi M, Brötz E, Rosenkränzer B, et al. Generation of new compounds through unbalanced transcription of landomycin A cluster. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol, 2016, 100(21): 9175-9186. DOI:10.1007/s00253-016-7721-3

|

| [38] |

Fidan O, Yan RM, Gladstone G, et al. New insights into the glycosylation steps in the biosynthesis of Sch47554 and Sch47555. Chem Bio Chem, 2018, 19(13): 1424-1432. DOI:10.1002/cbic.201800105

|

| [39] |

Forget SM, Na J, McCormick NE, et al. Biosynthetic 4, 6-dehydratase gene deletion: isolation of a glucosylated jadomycin natural product provides insight into the substrate specificity of glycosyltransferase JadS. Org Biomol Chem, 2017, 15(13): 2725-2729. DOI:10.1039/C7OB00259A

|

| [40] |

Huang CS, Yang CF, Fang ZJ, et al. Discovery of stealthin derivatives and implication of the amidotransferase FlsN3 in the biosynthesis of nitrogen-containing fluostatins. Mar Drugs, 2019, 17(3): 150. DOI:10.3390/md17030150

|

| [41] |

Zhou ZX, Xu QQ, Bu QT, et al. Genome mining-directed activation of a silent angucycline biosynthetic gene cluster in Streptomyces chattanoogensis. Chem Bio Chem, 2015, 16(3): 496-502. DOI:10.1002/cbic.201402577

|

| [42] |

Li ZY, Bu QT, Wang J, et al. Activation of anthrachamycin biosynthesis in Streptomyces chattanoogensis L10 by site-directed mutagenesis of rpoB. J Zhejiang Univ Sci B, 2019, 20(12): 983-994. DOI:10.1631/jzus.B1900344

|

| [43] |

Ziemert N, Alanjary M, Weber T. The evolution of genome mining in microbes—a review. Nat Prod Rep, 2016, 33(8): 988-1005. DOI:10.1039/C6NP00025H

|

| [44] |

Ward AC, Allenby NEE. Genome mining for the search and discovery of bioactive compounds: the Streptomyces paradigm. FEMS Microbiol Lett, 2018, 365(24): fny240.

|

| [45] |

Jin J, Yang XY, Liu T, et al. Fluostatins M-Q featuring a 6-5-6-6 ring skeleton and high oxidized a-rings from marine Streptomyces sp. PKU-MA00045. Mar Drugs, 2018, 16(3): 87. DOI:10.3390/md16030087

|

| [46] |

Malmierca GM, González-Montes L, Pérez-Victoria I, et al. Searching for glycosylated natural products in actinomycetes and identification of novel macrolactams and angucyclines. Front Microbiol, 2018, 9: 39. DOI:10.3389/fmicb.2018.00039

|

| [47] |

Yang XY, Jin J, Zhou MJ, et al. Discovery of angucyclinone polyketides from marine actinomycetes with a genomic DNA-based PCR assay targeting type Ⅱ polyketide synthase. J Chin Pharm Sci, 2017, 26(3): 171-179.

|

| [48] |

Liu T, Jin J, Yang XY, et al. Discovery of a phenylamine-incorporated angucyclinone from marine Streptomyces sp. PKU-MA00218 and generation of derivatives with phenylamine analogues. Org Lett, 2019, 21(8): 2813-2817. DOI:10.1021/acs.orglett.9b00800

|

| [49] |

Cruz JC, Maffioli SI, Bernasconi A, et al. Allocyclinones, hyperchlorinated angucyclinones from Actinoallomurus. J Antibiot (Tokyo), 2017, 70(1): 73-78. DOI:10.1038/ja.2016.62

|

| [50] |

Ren X, Lu XH, Ke AB, et al. Three novel members of angucycline group from Streptomyces sp. N05WA963. J Antibiot (Tokyo), 2011, 64(4): 339-343. DOI:10.1038/ja.2011.4

|

| [51] |

Nakagawa K, Hara C, Tokuyama S, et al. Saprolmycins A–E, new angucycline antibiotics active against Saprolegnia parasitica. J Antibiot (Tokyo), 2012, 65(12): 599-607. DOI:10.1038/ja.2012.86

|

| [52] |

Igarashi M, Watanabe T, Hashida T, et al. Waldiomycin, a novel WalK-histidine kinase inhibitor from Streptomyces sp. MK844-mF10. J Antibiot (Tokyo), 2013, 66(8): 459-464. DOI:10.1038/ja.2013.33

|

| [53] |

Fakhruzzaman M, Inukai Y, Yanagida Y, et al. Study on in vivo effects of bacterial histidine kinase inhibitor, waldiomycin, in Bacillus subtilis and Staphylococcus aureus. J Gen Appl Microbiol, 2015, 61(5): 177-184. DOI:10.2323/jgam.61.177

|

| [54] |

Mullowney MW, hAinmhire EÓ, Tanouye U, et al. A pimarane diterpene and cytotoxic angucyclines from a marine-derived Micromonospora sp. in Vietnam's East Sea. Mar Drugs, 2015, 13(9): 5815-5827. DOI:10.3390/md13095815

|

| [55] |

Awang AFI, Ahmed QU, Ali Shah SA, et al. Isolation and characterization of novel antibacterial compound from an untapped plant, Stereospermum fimbriatum. Nat Prod Res, 2018, 34(5): 629-637.

|

| [56] |

Bao J, He F, Li YM, et al. Cytotoxic antibiotic angucyclines and actinomycins from the Streptomyces sp. XZHG99T. J Antibiot (Tokyo), 2018, 71(12): 1018-1024. DOI:10.1038/s41429-018-0096-1

|

| [57] |

Voitsekhovskaia I, Paulus C, Dahlem C, et al. Baikalomycins A–C, new aquayamycin-type angucyclines isolated from Lake Baikal derived Streptomyces sp. IB201691-2A. Microorganisms, 2020, 8(5): 680. DOI:10.3390/microorganisms8050680

|

| [58] |

Chang YM, Xing L, Sun CX, et al. Monacycliones G–K and ent-gephyromycin A, angucycline derivatives from the marine-derived Streptomyces sp. HDN15129. J Nat Prod, 2020, 83(9): 2749-2755. DOI:10.1021/acs.jnatprod.0c00684

|

| [59] |

Yang L, Hou LK, Li HY, et al. Antibiotic angucycline derivatives from the deepsea-derived Streptomyces lusitanus. Nat Prod Res, 2020, 34(24): 3444-3450. DOI:10.1080/14786419.2019.1577835

|

| [60] |

Zhang WJ, Liu Z, Li SM, et al. Fluostatins I–K from the South China sea-derived micromonospora rosaria SCSIO N160. J Nat Prod, 2012, 75(11): 1937-1943. DOI:10.1021/np300505y

|

| [61] |

Huang HB, Yang TT, Ren XM, et al. Cytotoxic angucycline class glycosides from the deep sea actinomycete Streptomyces lusitanus SCSIO LR32. J Nat Prod, 2012, 75(2): 202-208. DOI:10.1021/np2008335

|

| [62] |

Lai ZZ, Yu JC, Ling HP, et al. Grincamycins I–K, cytotoxic angucycline glycosides derived from marine-derived actinomycete Streptomyces lusitanus SCSIO LR32. Planta Med, 2018, 84(3): 201-207. DOI:10.1055/s-0043-119888

|

| [63] |

Xie ZP, Liu B, Wang HP, et al. Kiamycin, a unique cytotoxic angucyclinone derivative from a marine Streptomyces sp. Mar Drugs, 2012, 10(3): 551-558.

|

| [64] |

Song YX, Liu GF, Li J, et al. Cytotoxic and antibacterial angucycline- and prodigiosin- analogues from the deep-sea derived Streptomyces sp. SCSIO 11594. Mar Drugs, 2015, 13(3): 1304-1316. DOI:10.3390/md13031304

|

| [65] |

Hu ZJ, Qin LL, Wang QQ, et al. Angucycline antibiotics and its derivatives from marine-derived actinomycete Streptomyces sp. A6H. Nat Prod Res, 2016, 30(22): 2551-2558. DOI:10.1080/14786419.2015.1120730

|

| [66] |

Xie ZP, Zhou L, Guo L, et al. Grisemycin, a bridged angucyclinone with a methylsulfinyl moiety from a marine-derived Streptomyces sp. Org Lett, 2016, 18(6): 1402-1405. DOI:10.1021/acs.orglett.6b00332

|

| [67] |

Guo L, Xie ZP, Yang Q, et al. Kiamycins B and C, unusual bridged angucyclinones from a marine sediment-derived Streptomyces sp.. Tetrahed Lett, 2018, 59(22): 2176-2180. DOI:10.1016/j.tetlet.2018.04.063

|

| [68] |

Zhou B, Ji YY, Zhang HJ, et al. Gephyyamycin and cysrabelomycin, two new angucyclinone derivatives from the Streptomyces sp. HN-A124. Nat Prod Res, 2019, 1-6. DOI:10.1080/14786419.2019.1660336

|

| [69] |

Yixizhuoma, Ishikawa N, Abdelfattah MS, et al. Elmenols C-H, new angucycline derivatives isolated from a culture of Streptomyces sp. IFM 11490. J Antibiot (Tokyo), 2017, 70(5): 601-606. DOI:10.1038/ja.2016.158

|

| [70] |

Ma XY, Wang GY, Zhang ZY, et al. Two glucosylated angucyclines from deep-sea-derived Streptomyces sp. PKU-MA01297. J Chin Pharm Sci, 2019, 28(12): 835-842. DOI:10.5246/jcps.2019.12.079

|

| [71] |

Zhang SM, Zhang L, Kou LJ, et al. Isolation, stereochemical study, and racemization of (±)-pratenone A, the first naturally occurring 3-(1-naphthyl)-2-benzofuran-1(3H)-one polyketide from a marine-derived actinobacterium. Chirality, 2020, 32(3): 299-307. DOI:10.1002/chir.23178

|

| [72] |

Gui C, Liu YN, Zhou ZB, et al. Angucycline glycosides from mangrove-derived Streptomyces diastaticus subsp. SCSIO GJ056. Mar Drugs, 2018, 16(6): 185. DOI:10.3390/md16060185

|

| [73] |

Peng AH, Qu XY, Liu FY, et al. Angucycline glycosides from an intertidal sediments strain Streptomyces sp. and their cytotoxic activity against Hepatoma Carcinoma cells. Mar Drugs, 2018, 16(12): 470. DOI:10.3390/md16120470

|

| [74] |

Abdelmohsen UR, Bayer K, Hentschel U. Diversity, abundance and natural products of marine sponge-associated actinomycetes. Nat Prod Rep, 2014, 31(3): 381-399. DOI:10.1039/C3NP70111E

|

| [75] |

Vicente J, Stewart AK, Van Wagoner RM, et al. Monacyclinones, new angucyclinone metabolites isolated from Streptomyces sp. M7_15 associated with the Puerto Rican sponge Scopalina ruetzleri. Mar Drugs, 2015, 13(8): 4682-4700. DOI:10.3390/md13084682

|

| [76] |

Guo ZK, Wang T, Guo Y, et al. Cytotoxic angucyclines from amycolatopsis sp. HCa1, a rare actinobacteria derived from Oxya chinensis. Planta Med, 2011, 77(18): 2057-2060. DOI:10.1055/s-0031-1280097

|

| [77] |

Shaaban KA, Ahmed TA, Leggas M, et al. Saquayamycins G–K, cytotoxic angucyclines from Streptomyces sp. Including two analogues bearing the aminosugar rednose. J Nat Prod, 2012, 75(7): 1383-1392. DOI:10.1021/np300316b

|

| [78] |

Boonlarppradab C, Suriyachadkun C, Rachtawee P, et al. Saccharosporones A, B and C, cytotoxic antimalarial angucyclinones from Saccharopolyspora sp. BCC 21906. J Antibiot (Tokyo), 2013, 66(6): 305-309. DOI:10.1038/ja.2013.16

|

| [79] |

Rabia-Boukhalfa YH, Eveno Y, Karama S, et al. Isolation, purification and chemical characterization of a new angucyclinone compound produced by a new halotolerant Nocardiopsis sp. HR-4 strain. World J Microbiol Biotechnol, 2017, 33(6): 126. DOI:10.1007/s11274-017-2292-8

|

| [80] |

Chen CX, Song FH, Guo H, et al. Isolation and characterization of LS1924A, a new analog of emycins. J Antibiot (Tokyo), 2012, 65(8): 433-435. DOI:10.1038/ja.2012.39

|

| [81] |

Jiang YJ, Gan LS, Ding WJ, et al. Cytotoxic gephyromycins from the Streptomyces sp. SS13I. Tetrahedron Lett, 2017, 58(38): 3747-3750. DOI:10.1016/j.tetlet.2017.08.035

|

| [82] |

Kalyon B, Tan GY, Pinto JM, et al. Langkocyclines: novel angucycline antibiotics from Streptomyces sp. Acta 3034. J Antibiot (Tokyo), 2013, 66(10): 609-616. DOI:10.1038/ja.2013.53

|

| [83] |

Wang L, Wang L, Zhou Z, et al. Cangumycins A–F, six new angucyclinone analogues with immunosuppressive activity from Streptomyces. Chin J Nat Med, 2019, 17(12): 982-987.

|

| [84] |

Dan VM, Vinodh JS, Sandesh CJ, et al. Molecular networking and whole-genome analysis aid discovery of an angucycline that inactivates mTORC1/C2 and induces programmed cell death. ACS Chem Biol, 2020, 15(3): 780-788. DOI:10.1021/acschembio.0c00026

|

| [85] |

Kim JW, Kwon Y, Bang S, et al. Unusual bridged angucyclinones and potent anticancer compounds from Streptomyces bulli GJA1. Org Biomol Chem, 2020, 18(41): 8443-8449. DOI:10.1039/D0OB01851A

|

| [86] |

Steele AD, Teijaro CN, Yang D, et al. Leveraging a large microbial strain collection for natural product discovery. J Biol Chem, 2019, 294(45): 16567-16576. DOI:10.1074/jbc.REV119.006514

|

| [87] |

Blin K, Shaw S, Kautsar SA, et al. The antiSMASH database version 3: increased taxonomic coverage and new query features for modular enzymes. Nucleic Acids Res, 2021, 49(D1): D639-D643. DOI:10.1093/nar/gkaa978

|

| [88] |

Rudolf JD, Yan XH, Shen B. Genome neighborhood network reveals insights into enediyne biosynthesis and facilitates prediction and prioritization for discovery. J Ind Microbiol Biotechnol, 2016, 43(2/3): 261-276.

|

| [89] |

Hindra, Huang TT, Yang D, et al. Strain prioritization for natural product discovery by a high-throughput real-time PCR method. J Nat Prod, 2014, 77(10): 2296-2303. DOI:10.1021/np5006168

|

| [90] |

Yan XH, Ge HM, Huang TT, et al. Strain prioritization and genome mining for enediyne natural products. mBio, 2016, 7(6): e02104-16.

|

| [91] |

Yan XH, Chen JJ, Adhikari A, et al. Genome mining of Micromonospora yangpuensis DSM 45577 as a producer of an anthraquinone-fused enediyne. Org Lett, 2017, 19(22): 6192-6195. DOI:10.1021/acs.orglett.7b03120

|

| [92] |

Quinn RA, Nothias LF, Vining O, et al. Molecular networking as a drug discovery, drug metabolism, and precision medicine strategy. Trends Pharmacol Sci, 2017, 38(2): 143-154. DOI:10.1016/j.tips.2016.10.011

|

| [93] |

Shen B. A new golden age of natural products drug discovery. Cell, 2015, 163(6): 1297-1300. DOI:10.1016/j.cell.2015.11.031

|

| [94] |

Fan KQ, Zhang Q. The functional differentiation of the post-PKS tailoring oxygenases contributed to the chemical diversities of atypical angucyclines. Synth Syst Biotechnol, 2018, 3(4): 275-282. DOI:10.1016/j.synbio.2018.11.001

|

| [95] |

Pan GH, Gao XQ, Fan KQ, et al. Structure and function of a C-C bond cleaving oxygenase in atypical angucycline biosynthesis. ACS Chem Biol, 2017, 12(1): 142-152. DOI:10.1021/acschembio.6b00621

|

2021, Vol. 37

2021, Vol. 37