中国科学院微生物研究所、中国微生物学会主办

文章信息

- 曹蒋军, 吴宗辉, 童廷婷, 朱庆宗, 赵二虎, 崔红娟

- Cao Jiangjun, Wu Zonghui, Tong Tingting, Zhu Qingzong, Zhao Erhu, Cui Hongjuan

- 间质表皮转化因子MET信号通路及其在肿瘤中的研究进展

- Advances in mesenchymal to epithelial transition factor signaling pathway and inhibitors

- 生物工程学报, 2018, 34(3): 334-351

- Chinese Journal of Biotechnology, 2018, 34(3): 334-351

- 10.13345/j.cjb.170265

-

文章历史

- Received: July 3, 2017

- Accepted: September 25, 2017

2 西南大学 西南大学医院,重庆 400716;

3 西南大学 动物科技学院,重庆 400716

2 Hospital of Southwest University, Southwest University, Chongqing 400716, China;

3 College of Animal Science and Technology, Southwest University, Chongqing 400716, China

近年来酪氨酸激酶(Protein tyrosine kinases,PTKs)作为抗肿瘤药物靶点,以其为导向的药物研发已逐步发展,具有广阔的应用前景。受体酪氨酸激酶MET基因,全称间质表皮转化因子(Mesenchymal to epithelial transition factor,MET),又称细胞间质表皮转化因子(Cellular-mesenchymal to epithelial transition factor,c-Met)或者肝细胞生长因子受体(Hepatocyte growth factor receptor,HGFR)等,属于PTKs家族的一员,位于人类第7条染色体(7q21-q31)区域,总长度超过120 kb,其中包含21个外显子以及20个内含子[1]。MET基因所编码的蛋白通过水解形成α和β亚基,再通过二硫键的连接组成成熟的受体蛋白MET。MET蛋白不仅对于组织损伤的修复以及再生有积极的促进作用[2],其介导的信号通路还对肿瘤细胞的生存、增殖和转移发挥着重要的作用[3]。本文将结合目前本实验室的研究,对MET的功能作用及其在治疗肿瘤的临床应用等方面展开综述。

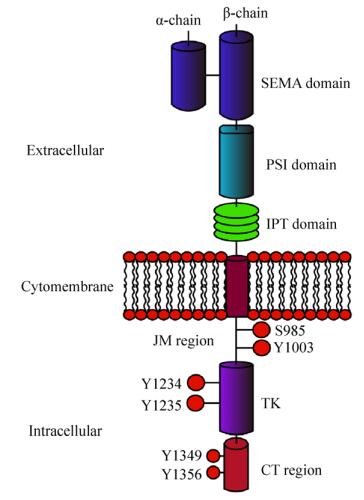

1 MET的结构与功能受体酪氨酸激酶MET基因所编码的蛋白MET大小约为170 kDa,经糖基化修饰后约为190 kDa,最终通过剪切作用形成由二硫键连接的两条多肽链,即α链(50 kDa)和β链(140 kDa)[4]。MET蛋白从膜外到胞内可划分为SEMA结构域(Semaphorin domain,SEMA)、PSI结构域(Plexin-semaphorin-integrin domain,PSI)、4个免疫球蛋白样重复结构域(Immunoglobulin-plexins-transcription domain,IPT)、一个跨膜域(Transmembrane region)、一个近膜域(Juxtamembrane region,JM)、酪氨酸激酶结构域(Tyrosine kinase domain,TK)和一个羧基末端的尾部区域(Carboxyl terminal region,CT) (图 1)[5-6]。

SEMA结构域是配体结合的重要元素,具有高度的保守性,其所包含的七叶-β-螺旋桨性折叠结构被认为是配体结合的关键部件,特别是与配体肝细胞生长因子HGF的结合起着关键作用[7]。肝细胞生长因子(Hepatocyte growth factor,HGF),又名扩散因子(Scatter factor,SF),主要由间充质细胞通过旁分泌的方式产生;HGF是目前已知的唯一高亲和性的MET配体[8]。与SEMA结构域相连的是PSI结构域,之所以称为PSI结构域是因为其存在丛状蛋白(Plexins)、脑信号蛋白(Semaphorins)以及整合素(Integrins)的半胱氨酸富集结构域[9];通常认为PSI结构域的存在使得配体能够更好地与MET结合[10]。位于PSI结构域下游的是包含4个免疫球蛋白重复结构的IPT结构域,有研究发现SEMA结构域并不是HGF结合MET的唯一位点,IPT的第3和第4个重复结构同样能对HGF产生高度亲和力[11]。MET的跨膜域和绝大多数酪氨酸激酶一样为单一的α螺旋[12]。位于胞质内氨基最末端的近膜域,在JM区域存在着S985、Y1003两个磷酸位点,其中S985的磷酸化能够负调控酪氨酸激酶的活性,而磷酸化的Y1003能够通过募集E3泛素连接酶c-Cbl,使得MET泛素化进而与吞蛋白相互作用导致MET的降解。在这个降解过程中,位于JM区域的富含脯氨酸(P)、谷氨酰胺(E)、丝氨酸(S)、苏氦酸(T)的PEST序列可能是被泛素化的位点[13],且也有报道称一个特定的蛋白质酪氨酸磷酸酶(PTP-S)也结合于该位点[13]。位于JM区域更下游的区域是TK域,与胰岛素生长因子Ⅰ受体以及免疫调节分子Tryo 3家族具有同源性。当MET与HGF结合后,处于TK域激活循环的Y1234和Y1235酪氨酸残基自发磷酸化,而处于碳末端区域的Y1349与Y1356残基的磷酸化能够形成一个多功能的结合位点;这个位点能够与细胞内的适配器结合并通过适配器募集许多胞内信号影响因子,从而诱导激酶的活性[14]。迄今为止,被发现包含于MET通路的衔接蛋白以及直接与激酶结合的底物包括生长因子受体结合蛋白2 (Growth factor receptor-bound protein 2,GRB2)、GRB2相关结合蛋白1 (GRB-2-associated binder 1,GAB1)、磷脂酰肌醇3-激酶(Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase,PI3K)、磷酸脂酶C-γ (Phospholipase C-γ,PLCγ)、衔接蛋白SHC和蛋白酪氨酸磷酸酶SRC、SHP2、SHIP1及STAT3等[15]。

2 MET参与信号通路所行使的功能MET主要在肺、肝、肾、胰腺、前列腺以及支气管等器官的上皮细胞中表达,而HGF主要由间充质细胞通过旁分泌的方式产生,其能引起MET的两个酪氨酸残基Y1234和Y1235的同源二聚作用和磷酸化,进而形成一个串联的SH2结构域(Src homology 2 domain)识别体,再通过与GRB2、GAB1、SHC、PI3K、PLCγ、SRC、SHIP2以及STAT3等蛋白的作用参与下游通路的调节。目前的研究中,MET主要参与调节以及行使的生物学功能见图 2,但在不同的组织和细胞中MET所参与的信号调节通路也有所不同,且其调控其下游的信号通路的作用机制也有待明确。因此,我们将对MET的高度保守的核心区域所参与的信号通路进行简单综述。

整合素(Integrin)又称为整合蛋白,是一种介导细胞和其外环境之间连接的跨膜受体,即能作为组成细胞外基质(Cell-extracellular matrix,ECM)蛋白的受体,如纤连蛋白、玻连蛋白、层粘连蛋白以及胶原蛋白[6]。整合素与ECM组成蛋白的相互作用能够对细胞与细胞之间、细胞与ECM之间的粘连起到关键的调节作用;其通过与蛋白的结合引起整合素的聚集,从而与细胞骨架联系促使细胞与ECM的黏附作用[6, 15-16]。有研究发现HGF同样能够引起整合蛋白的聚集,增加细胞的侵袭性[17]。此外,之前的研究发现整合素α6β4可作为HGF/MET的粘附受体进而调控细胞侵袭的能力;这说明整合素参与了由HGF/MET所引起的促进细胞侵袭的过程。研究者发现整合素蛋白α6β4可作为MET的粘附受体进而调控细胞侵袭的能力,而整合素蛋白α5β1同样可以通过MET对肿瘤血管的生成产生影响;这些证据说明整合素蛋白参与了由MET蛋白所引起的促进细胞侵袭及血管生成的过程[18-19]。在转基因Met小鼠的动物模型试验中,Wang等发现在缺乏HGF的情况下,整合素聚集引起的细胞黏附作用能够激活Met并维持其活性,进而引起肝癌的产生[20]。目前已经发现了很多在没有配体的情况下能够被激活的生长因子受体,其作用方式就是由整合素引起的细胞粘连所激活[21]。这进一步证明了整合素可能单独参与了激活MET蛋白的过程。

2.2 生长因子受体结合蛋白GRB2及其结合蛋白GAB1GRB2与GAB1都是参与MET调节下游通路重要的衔接蛋白;其中GAB1能直接与MET结合或通过GRB2间接地与MET结合被磷酸化;磷酸化的GAB1可以产生与其下游信号因子所结合的位点,进而激活PI3K/AKT通路,Ras、Rac1和MAPK级联反应等[6, 22-23]。GAB1能与MET结合,是因为GAB1含有13个氨基酸残基构成的MET偶联序列(MET-binding sequence,MBS),该序列位点能直接与MET碳末端的Y1349相互作用并被磷酸化[24]。GRB2与MET的相互作用不仅能够聚集GAB1,还对于K-RAS的激活十分关键[25]。GAB1通过其碳末端的SH3结构域(Src homology 3 domain)与GRB2相互作用,这种作用能够稳定GAB1与MET之间的作用[26]。所以当GRB2与MET分离时,GAB1与MET的作用将会受到影响。GAB1能够为MET的激活提供许多底物,其中包括PLCγ、Shc、Shp2、GRB2以及PI3K;而PI3K、PLCγ或者Shp2与GAB1分离的时候也会影响到MET所介导的分支化形态发生[6]。在通过敲除Gabl基因纯合子的胚胎实验中,研究者发现了类似敲除HGF/Met所导致的胎盘缺陷以及在肌肉组织中无迁徙前体细胞的缺陷[27]。由此可见,在衔接蛋白GAB1和GRB2的存在下,HGF/MET可产生多效应刺激,进而对细胞的周期进程、上皮形态发生、血管内皮细胞类型的分支化形态发生以及迁移能力产生影响[15, 22, 28]。

2.3 PI3K/AKT和Ras/MAPK信号通路PI3K/AKT是由MET所调控的下游通路,其作用主要是促进细胞生长增殖的能力[6]。PI3K的p85亚基不仅能直接与MET结合,还可通过GAB1间接与MET作用[29-30]。激活的PI3K-AKT通路可以诱导抗凋亡蛋白BCL2与BCL-XL的表达,从而维持和增强细胞生存的信号[31]。此外,PI3K也参与由HGF/MET诱导的细胞迁移过程[32]。不仅如此,PI3K/AKT还通过与SRC的结合影响了由HGF介导的NF-κB激活过程[33]。SRC是一种非受体酪氨酸激酶,在HGF/MET所参与的信号通路中起到主要的调节作用;此外,SRC还参与由HGF/MET诱导的肿瘤细胞的迁移能力[34]。整合素蛋白β1通过激活MET-SRC-FAK链式反应能够诱导细胞的迁移和侵袭,促进非贴壁细胞的生长,且SRC能够对MET的激活提供正向反馈[35]。Ras/MAPK通路也是目前研究比较透彻的MET下游信号通路,Ras/MAPK的激活需要SHC与GRB2通过Y1356与活化的MET相结合;激活的GTP结合蛋白Ras能够诱导肿瘤的发生及转移性的扩散[25],同时MET也能通过MAPK的介导增强细胞生长、增殖和迁移的能力[36]。

2.4 其他靶基因或信号通路HGF/MET能够影响上皮形态发生和血管内皮细胞类型的分支化形态发生及细胞的迁移侵袭能力;在细胞侵袭或分支形态发生时,细胞运动的驱动力源自于细胞骨架肌动蛋白的动态变化,这个过程由Ras同源基因家族(Ras homolog gene family,Rho)中的细胞分裂周期蛋白42 (Cell division control protein 42,CDC42)、Ras相关的C3肉毒素底物1 (Ras-related C3 botulinum toxin substrate 1,Rac1)以及Rho酶A (Rho member A,RhoA)所控制;CDC42能够促进丝状伪足以及微端丝的形成,而Rac1能够诱导板状伪足以及胞膜边缘波动[6]。HGF能够诱导CDC42、Rac1以及RhoA的激活完成上述的生理功能[37],但MET是如何激活Rho家族,其作用方式还需要进一步研究。另外,细胞外基质ECM中的不同成分也能够调节HGF/MET所诱导的分支以及管腺增生,例如参与ECM的降解与重组的尿激酶型纤溶酶原激活物(Urokinase plasminogen activator,uPA)和基质金属蛋白酶家族(Matrix metalloproteases,MMPs)。HGF/MET能够增加uPA以及其受体的表达,使其活性得到加强。另外,HGF也能够诱导MMPs的表达[38];且MMPs是由HGF/MET诱导的乳腺上皮细胞分支形态发生的必需因子[39];本实验室的研究也证实MET的上调可以增加MMPs的表达量,进而增强肿瘤细胞的侵袭能力(数据未发表)。由此可知HGF/MET可以通过调控uPA与MMPs的活性来影响细胞的侵袭能力[39]。总之,这些研究表明HGF/MET能够通过下游靶基因或信号通路来调控细胞的分支形态发生以及侵袭迁移能力。

文中,AKT:蛋白激酶B;CDC42:细胞分裂周期蛋白42;EGFR:表皮生长因子受体;ERK:胞外调节蛋白激酶;FAK:局部粘着斑酪氨酸激酶;GRB2:生长因子受体结合蛋白2;GAB1:GRB2结合蛋白1;HER2:人表皮生长因子受体;HGF:肝细胞生长因子;mTOR:哺乳动物雷帕霉素靶蛋白;PI3K:磷脂酰肌醇-3激酶;Plexin B:从状蛋白B;RAF:丝/苏氨酸蛋白激酶;RAS:GTP结合蛋白;SOS:鸟苷释放蛋白;VEGFR:血管内皮生长因子受体;α6β4 integrin:整合素α6β4。

3 MET与肿瘤的关系 3.1 MET与肿瘤的预后很多原发性肿瘤中MET基因都呈现基因扩增或高表达的现象,包括肺癌、胃癌、结直肠癌、肝癌等。在肺癌中61%非小细胞肺癌(Non-small cell lung cancer,NSCLC)和35%小细胞肺癌(Small cell lung cancer,SCLC)都有MET基因扩增现象[40-41],且MET基因拷贝数高的NSCLC患者预后相对较差[42]。Zhang等的研究表明NSCLC组织的MET和HGF表达量显著高于正常肺组织的,且与NSCLC的淋巴管生成和淋巴结转移有关[43]。许多研究已经证实MET的基因扩增或高表达是NSCLC患者的不良预后因素之一[44]。在胃癌中MET也呈基因扩增或高表达的现象,这种现象与胃癌侵袭、转移和预后相关,但与患者的性别、年龄、肿瘤的大小、位置及分化程度无关[45-48]。有研究表明胃癌组织中MET表达量显著高于正常胃黏膜、慢性萎缩性胃炎和异常增生组织等;且在胃癌组织中,淋巴结转移的MET表达量也显著高于未转移的[49]。Sotoudeh等的研究也证实了上述结果,MET的高表达还与胃癌的淋巴结转移和血管侵袭有关[50]。还有研究表明10%−20%的胃癌患者中存在着MET基因扩增的现象[45];Peng等的研究显示MET的基因扩增也是胃癌患者预后不良因素之一,MET基因扩增患者的总生存期和无病生存期显著缩短[46]。此外,MET能否作为结直肠癌预后的指标存在争议,但多项研究显示MET的高表达与患者的预后不良具有密切关系[51-52],但Qian等的研究发现MET表达量在结直肠癌原发灶和肝转移灶无显著性差异,因此MET不适合作为结直肠癌的预后标志物[53-54]。此外,Cai等研究揭示MET表达水平与肝癌的术后复发、生存时间关系密切,且表达低的可获得良好的手术效果,这提示MET可作为肝癌术后预后指标[55]。此外,MET基因扩增是肿瘤细胞产生耐药性的重要原因之一。MET扩增导致MET受体表达量异常增加,酪氨酸激酶活性进一步增强,进而会过度激活下游通路的信号转导,特别是PI3K/AKT信号通路,使细胞获得耐药能力[56-57]。

另外,在很多原发性癌症中也发现了MET突变,例如在遗传性乳头状肾癌(Heredit-ary papillary renal cell carcinoma,HPRC)和头颈部鳞状细胞癌(Squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck,SCCHN)中发现MET蛋白TK结构域的突变,而在胃癌、乳腺癌及小细胞肺癌中则发现MET蛋白JM区域或SEMA结构域的突变[58-60]。MET蛋白突变位点包括位于TK结构域的D1228H/N、M1250T、L1195V和Y1230C等,JM区域的T1010I、P1009S、R988C和SEMA结构域的N375S和E168D等[58, 61-62]。TK结构域的突变可影响MET的激酶活性,JM区域的突变可影响配体结合的亲和力,而SEMA结构域的突变点可影响MET蛋白泛素化降解的作用[63]。有研究报道了283例肺癌患者(141例东亚人、76例高加索人和66例非裔美国人)的MET蛋白突变状况的检测分析,结果显示所有的非同义突变均出现SEMA结构域和JM区域,而TK结构域未发现突变位点[64]。

3.2 HGF/MET对肿瘤发生发展及肿瘤耐药性的影响 3.2.1 HGF/MET与肿瘤发生发展的关系正常生理条件下,HGF配体由间质细胞分泌,MET受体由上皮细胞产生并存在于其细胞膜上,因此HGF和MET通过这种旁分泌机制调控机体正常组织的上皮-间质转化(Epithelial-mesenchymal transition,EMT)的作用,且这种旁分泌机制是受到机体严格调控的。有些肿瘤细胞会同时表达配体HGF和受体MET,由此可形成不受调控的闭合的自分泌环,在这种调控机制下HGF/MET可持续地被激活,进而过度活化包括PI3K/AKT、Ras/MAPK和STAT等信号转导的各级联途径,最终促进肿瘤细胞进入无限增殖的恶性循环,这可能是促进肿瘤发生发展的原因之一[65-66]。另外,有些肿瘤细胞还可以通过分泌白介素等细胞因子,刺激相邻的成纤维细胞分泌HGF配体,在它们之间也形成一个不受调控的闭合的环状作用机制,进而促进肿瘤的发生发展[67]。

3.2.2 HGF/MET与肿瘤微环境的关系HGF/MET信号通路不仅参与肿瘤细胞的发生发展,还同时参与肿瘤微环境的营造。肿瘤微环境主要包括ECM、血管、炎性细胞、巨噬细胞、树突细胞以及成纤维细胞等[68-69]。

1) HGF/MET诱导肿瘤新生血管的生成

肿瘤发生发展离不开血管为其提供的充足营养物质,因此新生血管对肿瘤的发生发展起着重要作用。HGF/MET信号通路的激活不仅能通过PI3K/AKT信号通路和STAT3等促进血管生成素、血管内皮细胞生长因子(Vascular endothelial growth factor,VEGF)等血管生成因子的表达;还可以通过MAPK等信号通路抑制血小板反应素-1 (Thrombospondin-1,TSP-1)的表达,而TSP-1则是血管生成素的强抑制因子[56, 68]。此外,在新血管形成或内皮细胞正在转移和增殖时,MET都呈高表达状态;而HGF可以直接刺激血管平滑肌细胞释放VEGF-A诱导新血管的生成。HGF还可以通过Rac特定鸟嘌呤核苷酸交换因子Asef和多功能Rac效应因子IQ模序的GTP酶活化蛋白1 (IQ motif-containing GTPase-activating protein 1,IQGAP1)来加强内皮细胞的屏障功能[23, 70]。总之,HGF/MET可与VEGF-A共同调控内皮细胞的增殖和转移,为血管的形成奠定基础[23]。

2) HGF/MET参与细胞外基质的降解

细胞外基质(Extracellular matrix,ECM)是细胞表面或细胞间的由多糖、蛋白等组成的网架结构物质。ECM是阻止肿瘤细胞转移的重要屏障,肿瘤细胞的迁移和侵袭首先需要降解ECM。降解ECM的降解酶主要为基质金属蛋白酶(Matrix metalloproteinases,MMPs)和尿激酶型纤溶酶原激活因子(Urokinase-type plasminogen activator,uPA)。而HGF/MET的激活不仅可以提高MMPs的表达,还可以通过MAPK信号通路来上调uPA的表达,进而加速ECM的降解,最终导致为肿瘤细胞迁移和侵袭创造适宜的微环境[56, 71]。

3) HGF/MET参与其他肿瘤微环境的营造

慢性炎症在肿瘤的发生发展中发挥着重要的作用,在肿瘤的炎症微环境存在着大量的炎性细胞,其可在肿瘤淋巴结转移(Tumor node metastasis,TNM)分期较低的阶段促进肿瘤细胞的增殖和转移[68]。与肿瘤相关的巨噬细胞在炎-癌转化中具有关键作用,它能通过影响MET蛋白的表达,进而通过HGF/MET促进肿瘤细胞的迁移能力[72]。树突细胞是现今发现的机体内功能最强的抗原递呈细胞,可激活静息的T细胞,进而诱发机体产生抗肿瘤免疫,而HGF/C-Met信号通路不仅能抑制其抗原呈递功能,还可抑制树突细胞对肿瘤组织的浸润[73-74]。

3.2.3 HGF/MET与肿瘤耐药性的关系HGF/MET信号通路无论在肿瘤原发性耐药还是继发性耐药中都发挥了重要作用[75]。有研究报道发现在表皮生长因子受体酪氨酸激酶抑制剂(Epidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor,EGFR-TKI)原发性耐药的肺腺癌细胞中,HGF/MET信号通路过度活化,能通过GAB1蛋白激活PI3K/AKT信号通路,降低EGFR-TKI对其转导信号级联反应的抑制,进而产生耐药性[75-76]。另外,Engelma等对吉非替尼产生获得性耐药的肺癌细胞系进行干预后,发现MET扩增可以通过表皮因子受体ERBB3蛋白的磷酸化激活其下游PI3K/AKT等信号通路,进而避开EGFR-TKI作用的药物靶点,最终导致细胞对EGFR-TKI产生继发性耐药[75]。

3.3 以HGF/MET为靶点的抗肿瘤治疗HGF/MET信号通路在多种肿瘤组织中出现异常活化,并与肿瘤细胞的生长、增殖和侵袭能力有着密切的关系。例如异常活化的HGF/MET信号通路与肺癌发生、浸润和转移有着密切联系[77];而在结直肠癌侵袭转移过程中,HGF/MET参与调控的上皮间质转化(Epithelial mesenchymal transition,EMT)发挥了关键的作用[78]。因此,阻断HGF/MET信号通路可有效抑制肿瘤的发生发展与转移;目前针对HGF/MET的抑制剂主要有3类:生物拮抗剂、单克隆抗体以及小分子抑制剂。

3.3.1 生物拮抗剂作用于HGF/MET通路的生物拮抗剂主要是HGF的变异体NK1、NK2和NK4等;其作用机制是和HGF配体竞争性地与MET结合,抑制由HGF所诱导的MET受体的酪氨酸磷酸化作用,从而降低HGF/MET通路的活性[56, 79]。NK2是天然的HGF蛋白变异体;而NK4人为设计的HGF的1个片段,目前已经证实在多种临床模型中都有完整的竞争性抑制HGF/MET通路的能力[80-81]。有研究报道通过腺病毒介导的稳定表达的NK4对肿瘤细胞的增殖以及对肺癌和黑色素瘤的迁移能力有明显的抑制作用[82];且在原位肿瘤移植的恶性胸膜间皮瘤动物模型中,NK4的表达显著抑制肿瘤细胞生长增殖和侵袭迁移的能力[83]。以上的研究结果表明通过NK4介导的基因治疗对癌症患者来说不失为一个行之有效的途径;而这种通过设计HGF的剪切体抑制HGF/MET信号通路活性,从而达到抗肿瘤效果的方式值得进一步思考和探索。

3.3.2 单克隆抗体针对HGF/MET信号通路的单克隆抗体多种多样,其中作用于HGF的抗体有Rilotumumab (AMG 102)、TAK701和Ficlatuzumab (AV299)等;作用于MET的有Onartuzumab、DN30和CE-355621等;其作用机制为通过抗体与抗原的作用,中和HGF (或MET)的活性,进而抑制其与MET (或HGF)的结合,最终降低HGF/MET通路的活性。

AMG102是一种完全的人源单克隆抗体,其能够与HGF的轻链结合,更易与双链的成熟HGF相结合。目前AMG102被作为单一的治疗方案在多种癌症中进行Ⅱ期临床试验评估,包括结直肠癌和胃食管腺癌等(表 1)[84]。TAK701是一种人源的抗HGF中和抗体,其作用机理是通过TAK701能够与HGF结合,从而阻断HGF与MET的连接。TAK701能够抑制细胞内MET的磷酸化并且对很多依赖于HGF自分泌的癌细胞有抗肿瘤的活性[85]。Ficlatuzumab (AV299)是人源化抗HGF IgG1的单克隆抗体,其已经在NSCLC患者中进行了Ⅱ期临床试验[56]。

| Inhibitor name | Type | Target | Cancer type | Phase | Arm | Status | Reference |

| Tivatinib | Selective kinase inhibitor; | MET | Colorectal cancer | Phase Ⅱ | Tivantinib (ARQ 197)+Cetuximab | Ongoing, not recruiting | NCTO1892527 |

| Non-ATP competitive |

Malignant solid tumor, Gastroesophageal cancer |

Phase Ⅰ/Ⅱ | Tivantinib+FOLFOX | Completed | NCT01611857 | ||

| Inoperable hepatocellular carcinoma |

Phase Ⅲ | ARQ197 Placebo |

Ongoing, not recruiting | NCT01755767 | |||

| Unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma |

Phase Ⅱ | ARQ197 Placebo |

Completed | NCT00988741 | |||

| Cirrhotic patients with hepatocellular carcinoma |

Phase Ⅰ | ARQ197 | Completed | NCT00802555 | |||

| Locally advanced or metastatic gastric cancer | Phase Ⅱ | ARQ 197 Oxaliplatin, capecitabine or irinotecan | Withdrawn prior to enrollment | NCT01070290 | |||

| Hepatocellular carcinoma |

Phase Ⅰ | ARQ 197 | Completed | NCT01656265 | |||

| Advanced solid tumors | Phase Ⅰ | ARQ 197 + Pazopanib | Completed | NCT01468922 | |||

| Previously treated advanced/recurrent gastric cancer | Phase Ⅱ | ARQ 197 | Completed | NCT01152645 | |||

| Hepatocellular carcinoma |

Phase Ⅰ/Ⅱ | E7050 + Sorafenib | Ongoing, not recruiting | NCT01271504 | |||

| Pancreatic neoplasms | Phase Ⅱ | ARQ 197 gemcitabine | Completed | NCT00558207 | |||

| Crizotinib | Multi-kinase inhibitor; ATP competitive | MET and ALK | Solid tumors | Phase Ⅱ | Crizotinib | Recruiting participants |

NCT02034981 |

| Gastric cancer | Phase Ⅱ | Crizotinib | Recruiting participants |

NCT02435108 | |||

| Colorectal cancer | Phase Ⅰ | Crizotinib+ PD-0325901 | Recruiting participants |

NCT02510001 | |||

| Advanced cancers | Phase Ⅱ | Crizotimb+ Dasatinib | Ongoing, but not recruiting participants | NCTO1744652 | |||

| Advanced cancer with several degrees of liver dysfunction | Phase Ⅰ | Crizotinib | Completed | NCT01576406 | |||

| Advanced tumors | Phase Ⅱ | Crizotinib | Recruiting | NCT01524926 | |||

| Cabozantinib (XL184) |

Multi-kinase inhibitor; ATP competitive | MET and VEGFR2 | Refractory soft tissue sarcomas | Phase Ⅱ | Cabozantinib | Recruiting | NCT01755195 |

| Advanced cholangiocarcinoma |

Phase Ⅱ | Cabozantinib | Ongoing, not recruiting | NCTO 1954745 | |||

| Colorectal cancer | Phase Ⅰ | Cabozantinib + Panitumumab Cabozantinib | Recruiting | NCT02008383 | |||

| Hepatocellular carcinoma |

Phase Ⅲ | Cabozantinib Placebo |

Recruiting | NCTO 1908426 | |||

| Solid tumors | Phase Ⅰ | Cabozantinib | Completed | NCT01553656 | |||

| JNJ-38877605 | Selective kinase inhibitor; ATP competitive | MET | Advanced or refractory solid tumors | Phase Ⅰ | JNJ-38877605 | Terminated | NCT00651365 |

| Golvatinib (E7050) |

Multi-kinase inhibitor; ATP competitive | MET, VEGFR-2, multiple member | Advanced solid tumors | Phase Ⅰ | E7050 | Completed | NCT00869895 |

| Eph receptor family, c-Kit and Ron | Solid tumor gastric cancer | Phase Ⅰ | E7050 | Completed | NCT01428141 | ||

| MK-2461 | Multi-kinase inhibitor; ATP competitive | MET, AKTand Ras |

Advanced cancer | Phase Ⅰ | MK-2461 | Completed | NCT00518739 |

| Advanced solid tumors | Phase Ⅰ/Ⅱ | MK-2461 | Completed | NCT00496353 | |||

| Rilotumumab (AMG 102) |

Antibody | Human HGF | Gastric cancer | Phase Ⅲ | AMG 102+Cisplatin+Capecitabine Placebo | Terminated | NCT02137343 |

| Advanced or metastatic gastric or esophagogastric junction cancer | Phase Ⅰ/Ⅱ | AMG102(Placebo)+Capecitabine+Epirubicin+Cisplatin | Terminated | NCT00719550 | |||

| Advanced solid tumors or advanced or metastatic gastric | Phase Ⅰ | Rilotumumab | Completed | NCT01791374 | |||

| Metastatic colorectal cancer | Phase Ⅱ | Panitumumab, Ganitumab, Rilotumumab Placebo, Panitumumab, Ganitumab |

Completed | NCT00788957 | |||

| Onartuzumab (MetMab) |

Monovalent monoclonal antibody |

Human MET | Gastric cancer | Phase Ⅱ | Placebo mFOLFOX6 onartuzumab | Completed | NCT01590719 |

| Advanced or metastatic solid tumors | Phase Ⅰ | MetMAb MetMAb+bevacizumab | Completed | NCTO1068977 | |||

| Solid tumor | Phase Ⅲ | Onartuzumab placebo |

Ongoing, but not recruiting | NCT02488330 | |||

| Advanced hepatocellular carcinom |

Phase Ⅰ | Onartuzumab Onartuzumab+Sorafenib |

Completed | NCT01897038 | |||

| Advanced or metastatic solid tumors | Phase Ⅰ | Onartuzumab (MetMAb) | Completed | NCT02031731 | |||

| AMG 208 | Selective kinase inhibitor | MET and RON | Advanced solid tumors | Phase Ⅰ | AMG 208 | Completed | NCT00813384 |

| MGCD265 | Multi-kinase inhibitor |

MET, Tek/Tie-2, VEGFR and MST1R (RON) | Advanced malignancies | Phase Ⅰ | MGCD265 | Completed | NCT00679133 |

| Foretinib (GSK1363089) |

Multi-kinase inhibitor; ATP competitive | Met, Ron, VEGFR1 to VEGFR3, PDGFR, Kit, Flt-3, Tie-2, AXL |

Solid tumor | Phase Ⅰ | Foretinib | Completed | NCT00742261 |

| Liver cancer | Phase Ⅰ | Foretinib | Completed | NCT00920192 | |||

| Metastatic gastric cancer | Phase Ⅱ | Foretinib | Completed | NCT00725712 | |||

| EMD1204831 | Selective kinase inhibitor; ATP competitive | MET | Advanced solid tumors | Phase Ⅰ | EMD1204831 | Terminated | NCT01110083 |

| INCB028060 | Selective kinase inhibitor; ATP competitive | MET | Advanced malignancies | Phase Ⅰ | INCB028060 | Completed | NCT01072266 |

| Amuvatinib | Multi-kinase inhibitor |

c-kit, PDGFRα; MET, Ret oncoprotein, mutant forms of Flt3 and PDGFR |

Solid tumors | Phase Ⅰ | Amuvatinib | Completed | NCT00894894 |

| BMS-777607 | Selective kinase inhibitor; ATP competitive | MET | Malignant solid tumor | Phase Ⅰ | BMS-777607 | Ongoing, not recruiting | NCT01721148 |

| Advanced or metastatic solid tumors | Phase Ⅰ/Ⅱ | BMS-777607 | Completed | NCT00605618 | |||

| AMG337 | Selective kinase inhibitor | MET | Stomach neoplasms | Phase Ⅰ/Ⅱ | AMG 337 | Ongoing, not recruiting | NCT02096666 |

| Advanced solid tumors | Phase Ⅰ | AMG337 | Ongoing, not recruiting | NCTO1253707 | |||

| Gastric/esophageal adenocarcinoma or other solid tumors | Phase Ⅱ | AMG 337 | Terminated | NCT02016534 | |||

| PF-04217903 | Selective kinase inhibitor; ATP competitive | MET | Advanced cancer | Phase Ⅰ | PF-04217903 | Terminated | NCT02016534 |

| MSC2156119J | Selective kinase inhibitor | MET | Solid tumors | Phase Ⅰ | MSC2156119J | Completed | NCT01832506 |

| Hepatocellular carcinoma |

Phase Ⅰ/Ⅱ | MSC2156119J | Recruiting | NCT02115373 | |||

| Advanced solid tumors | Phase Ⅰ | MSC2156119J | Completed | NCT01014936 | |||

| PF-02341066 | c-Tyrosine kinase inhibitor |

MET, HGF | Advanced cancer | Phase Ⅰ | PF-02341066, Rifampin, Itraconazole | Recruiting | NCT00585195 |

| Volitinib | Selective kinase inhibitor | MET | Advanced gastric adenocarcinoma | Phase Ⅱ | Volitinib | Recruiting | NCT02449551 |

| Advanced solid tumors | Phase Ⅰ | Volitinib | Recruiting | NCT01773018 | |||

| Advanced gastric cancer | Phase Ⅰ | Volitinib+Docetaxel | Completed | NCT02252913 |

Onartuzumab是一种人为设计的能与MET中和的单克隆抗体,目前处于临床前研究阶段,主要用于治疗胃癌、实体瘤、移性结直肠癌和晚期肝癌等(表 1)[84, 86-87]。DN30是MET的单克隆抗体,其抑制MET及丝/苏氨酸蛋白激酶的磷酸化,进而抑制肿瘤的生长和增殖,目前还处于临床前研究阶段[81]。CE-355621单克隆抗体与MET的结合位点位于胞外区,可以阻止MET与HGF的结合,进而抑制MET的激活,主要应用于神经胶质瘤等的治疗,目前也处于临床前研究阶段[81]。

3.3.3 小分子抑制剂绝大多数小分子抑制剂都是以MET受体为靶点的,其作用机制是通过与MET蛋白胞内ATP结合位点竞争性地结合,进而阻断酪氨酸磷酸化,最终达到抑制MET激酶活性的作用;根据小分子抑制剂针对MET的选择性,分为选择性及非选择性酪氨酸激酶抑制剂[81]。选择性酪氨酸激酶抑制剂主要有Crizotinib、Cabozantinib (XL184)、JNJ-38877605、Golvatinib (E7050)和MK-2461等(表 1)[84, 88];非选择性酪氨酸激酶抑制剂具有代表性的有Tivatinib、JNJ-38877605和PF-04217903等(表 1)[84]。

Crizotinib是目前唯一已上市的针对MET的小分子抑制剂。Crizotinib,中文名称克里唑替尼,商品名为XalkoriTM,是美国辉瑞公司(Pfizer)研发的针对MET配体和间变性淋巴瘤激酶(Anaplastic lymphoma kinase,ALK)的小分子抑制剂;该药早在2011年8月获得美国食品药品管理局(Food and Drug Administration,FDA)的加速批准,2013年11月获得正式批准,主要用于间变性淋巴瘤激酶阳性的转移性非小细胞肺癌患者的治疗[89-90]。有研究报道显示在非小细胞肺癌细胞系SPC-A1中,Crizotinib可以通过降低MET-RAS-MAPK和MET-PI3K-AKT等信号通路的活性,进而诱导肿瘤细胞产生自噬,最终抑制肿瘤的生长增殖[91]。

在Crizotinib的Ⅰ期临床试验中,给予119例间变性淋巴瘤激酶阳性的转移性非小细胞肺癌患者每天两次250 mg的剂量进行疗效评估,结果显示其客观响应率(Objective response rate,ORR)为61%,疾病无停顿生计期(Progression-free survival,PFS)为10个月,治疗的中位反应期(Median response duration)为48周[92-93]。在Ⅱ期临床试验中,136例患者进行了药物安全性评估,109例进行了患者报告结局评价(Patient reported outcome,PRO),76例进行了肿瘤反应评估;中位年龄为52岁,94%患有胰腺癌,68%无抽烟史和53%是女性。通过每日两次口服250 mg的Crizotinib治疗后,参与肿瘤反应评估的76例患者中,63例肿瘤病灶缩小(41例病灶缩小比例≥30%)[93-94]。在Crizotinib的Ⅲ期临床试验中,347例患者被随机分为Crizotinib组和标准化疗药物组(培美曲塞或多西他赛),结果显示其客观响应率为65%;Crizotinib组的中位PFS显著高于标准化疗药物组,即7.7个月对3个月(多西他赛,P < 0.000 1)或4.2个月(培美曲塞,P < 0.001)[95]。

4 总结与展望MET蛋白作为一种受体酪氨酸激酶,通常存在于上皮细胞中,被HGF等配体激活后,能够参与调控细胞的增殖、凋亡、迁移侵袭和细胞形态等多种生物学功能。MET参与的信号转导主要有Integrin、GRB2-GAB1、PI3K/AKT、Ras/MAPK和SRC/FAK等信号通路。随着研究的深入,MET已被证实在多种恶性肿瘤中异常表达或基因扩增,其与肿瘤细胞的生长增殖、迁移侵袭以及患者的预后都有密切的关系。近年来随着对MET在肿瘤方面研究的深入和扩展,其逐步成为抗肿瘤治疗的重要靶点;特别是针对HGF/MET靶向治疗的抑制剂很多目前已经进入了临床阶段的研究,且其良好的抗肿瘤效果也得到了证实。尽管如此,对于其抑制剂的安全性、耐药性及针对不同肿瘤的不同用法和用量等需还更加深入的研究。因此,进一步探究MET在肿瘤发生发展中的功能机制,才有可能找到一类肿瘤抑制活性高、选择性好和副作用小的抑制剂,为肿瘤治疗提供新途径和新方法。

| [1] | Yamashita JI, Ogawa M, Yamashita SI, et al. Immunoreactive hepatocyte growth factor is a strong and independent predictor of recurrence and survival in human breast cancer. Cancer Res, 1994, 54(7): 1630–1633. |

| [2] | Liu YH. Renal fibrosis: new insights into the pathogenesis and therapeutics. Kidney Int, 2006, 69(2): 213–217. DOI: 10.1038/sj.ki.5000054 |

| [3] | Miekus K. The Met tyrosine kinase receptor as a therapeutic target and a potential cancer stem cell factor responsible for therapy resistance (Review). Oncol Rep, 2016, 37(2): 647–656. |

| [4] | Matsumoto K, Umitsu M, de Silva DM, et al. Hepatocyte growth factor/MET in cancer progression and biomarker discovery. Cancer Sci, 2017, 108(3): 296–307. DOI: 10.1111/cas.13156 |

| [5] | Granito A, Guidetti E, Gramantieri L. c-MET receptor tyrosine kinase as a molecular target in advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatocell Carcinoma, 2015, 2: 29–38. |

| [6] | Petrini I. Biology of MET: a double life between normal tissue repair and tumor progression. Ann Transl Med, 2015, 3(6): 82. |

| [7] | Niemann HH, Jäger V, Butler PJG, et al. Structure of the human receptor tyrosine kinase met in complex with the Listeria invasion protein InlB. Cell, 2007, 130(2): 235–246. DOI: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.05.037 |

| [8] | Kim ES, Salgia R. MET pathway as a therapeutic target. J Thorac Oncol, 2009, 4(4): 444–447. DOI: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e31819d6f91 |

| [9] | Sattler M, Ma PC, Salgia R. Therapeutic targeting of the receptor tyrosine kinase Met. Cancer Treat Res, 2004, 119: 121–138. DOI: 10.1007/b105352 |

| [10] | Kozlov G, Perreault A, Schrag JD, et al. Insights into function of PSI domains from structure of the Met receptor PSI domain. Biochem Biophys Res Commun, 2004, 321(1): 234–240. DOI: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.06.132 |

| [11] | Basilico C, Arnesano A, Galluzzo M, et al. A high affinity hepatocyte growth factor-binding site in the immunoglobulin-like region of met. J Biol Chem, 2008, 283(30): 21267–21277. DOI: 10.1074/jbc.M800727200 |

| [12] | Ma PC, Maulik G, Christensen J, et al. c-Met: Structure, functions and potential for therapeutic inhibition. Cancer Metastasis Rev, 2003, 22(4): 309–325. DOI: 10.1023/A:1023768811842 |

| [13] | Villa-Moruzzi E, Puntoni F, Bardelli A, et al. Protein tyrosine phosphatase PTP-S binds to the juxtamembrane region of the hepatocyte growth factor receptor Met. Biochem J, 1998, 336(1): 235–239. DOI: 10.1042/bj3360235 |

| [14] | Comoglio PM, Boccaccio C. Scatter factors and invasive growth. Semin Cancer Biol, 2001, 11(2): 153–165. DOI: 10.1006/scbi.2000.0366 |

| [15] | Zhang YW, Woude GFV. HGF/SF-Met signaling in the control of branching morphogenesis and invasion. J Cell Biochem, 2003, 88(2): 408–417. DOI: 10.1002/jcb.v88:2 |

| [16] | Giancotti FG, Ruoslahti E. Transduction-integrin signaling. Science, 1999, 285(5430): 1028–1032. DOI: 10.1126/science.285.5430.1028 |

| [17] | Trusolino L, Cavassa S, Angelini P, et al. HGF/scatter factor selectively promotes cell invasion by increasing integrin avidity. FASEB J, 2000, 14(11): 1629–1640. DOI: 10.1096/fj.99-0844com |

| [18] | Trusolino L, Bertotti A, Comoglio PM. A signaling adapter function for α6β4 integrin in the control of HGF-dependent invasive growth. Cell, 2001, 107(5): 643–654. DOI: 10.1016/S0092-8674(01)00567-0 |

| [19] | Mitra AK, Sawada K, Tiwari P, et al. Ligand-independent activation of c-Met by fibronectin and α5β1-integrin regulates ovarian cancer invasion and metastasis. Oncogene, 2011, 30(13): 1566–1576. DOI: 10.1038/onc.2010.532 |

| [20] | Wang R, Ferrell DL, Faouzi S, et al. Activation of the Met receptor by cell attachment induces and sustains hepatocellular carcinomas in transgenic mice. J Cell Biol, 2001, 153(5): 1023–1034. DOI: 10.1083/jcb.153.5.1023 |

| [21] | Schwartz MA, Ginsberg MH. Networks and crosstalk: integrin signalling spreads. Nat Cell Biol, 2002, 4(4): E65–E68. DOI: 10.1038/ncb0402-e65 |

| [22] | Smith MA, Licata T, Lakhani A, et al. MET-GRB2 signaling-associated complexes correlate with oncogenic MET signaling and sensitivity to MET kinase inhibitors. Clin Cancer Res, 2017. DOI: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-16-3006 |

| [23] | Gallo S, Sala V, Gatti S, et al. Cellular and molecular mechanisms of HGF/Met in the cardiovascular system. Clin Sci (Lond), 2015, 129(12): 1173–1193. DOI: 10.1042/CS20150502 |

| [24] | Schaeper U, Gehring NH, Fuchs KP, et al. Coupling of Gab1 to c-Met, Grb2, and Shp2 mediates biological responses. J Cell Biol, 2000, 149(7): 1419–1432. DOI: 10.1083/jcb.149.7.1419 |

| [25] | Saucier C, Papavasiliou V, Palazzo A, et al. Use of signal specific receptor tyrosine kinase oncoproteins reveals that pathways downstream from Grb2 or Shc are sufficient for cell transformation and metastasis. Oncogene, 2002, 21(12): 1800–1811. DOI: 10.1038/sj.onc.1205261 |

| [26] | Furge KA, Zhang YW, Woude GFV. Met receptor tyrosine kinase: enhanced signaling through adapter proteins. Oncogene, 2000, 19(49): 5582–5589. DOI: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203859 |

| [27] | Sachs M, Brohmann H, Zechner D, et al. Essential role of Gab1 for signaling by the c-Met receptor in vivo. J Cell Biol, 2000, 150(6): 1375–1384. DOI: 10.1083/jcb.150.6.1375 |

| [28] | Rosário M, Birchmeier W. How to make tubes: signaling by the Met receptor tyrosine kinase. Trends Cell Biol, 2003, 13(6): 328–335. DOI: 10.1016/S0962-8924(03)00104-1 |

| [29] | Xiao GH, Jeffers M, Bellacosa A, et al. Anti-apoptotic signaling by hepatocyte growth factor/Met via the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/Akt and mitogen-activated protein kinase pathways. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA, 2001, 98(1): 247–252. DOI: 10.1073/pnas.98.1.247 |

| [30] | Ko B, He T, Gadgeel S, et al. MET/HGF pathway activation as a paradigm of resistance to targeted therapies. Ann Transl Med, 2017, 5(1): 4. DOI: 10.21037/atm |

| [31] | Liu YH. Hepatocyte growth factor in kidney fibrosis: therapeutic potential and mechanisms of action. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol, 2004, 287(1): F7–F16. DOI: 10.1152/ajprenal.00451.2003 |

| [32] | Usatyuk PV, Fu PF, Mohan V, et al. Role of c-Met/phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3k)/Akt signaling in hepatocyte growth factor (HGF)-mediated lamellipodia formation, reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation, and motility of lung endothelial cells. J Biol Chem, 2014, 289(19): 13476–13491. DOI: 10.1074/jbc.M113.527556 |

| [33] | Fan SJ, Gao M, Meng QH, et al. Role of NF-kappa B signaling in hepatocyte growth factor/scatter factor-mediated cell protection. Oncogene, 2005, 24(10): 1749–1766. DOI: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208327 |

| [34] | Gururajan M, Sievert M, Mink S, et al. SRC family kinase FYN promotes MET tyrosine kinase activation, epithelial to mesenchymal transition and metastasis in human prostate cancer. Cancer Res, 2014, 74(19): 3459. |

| [35] | Hui AY, Meens JA, Schick C, et al. Src and FAK mediate cell-matrix adhesion-dependent activation of Met during transformation of breast epithelial cells. J Cell Biochem, 2009, 107(6): 1168–1181. DOI: 10.1002/jcb.v107:6 |

| [36] | Lorenzon L, Ricca L, Pilozzi E, et al. Tumor regression grades, K-RAS mutational profile and c-MET in colorectal liver metastases. Pathol Res Pract, 2017, 213(8): 1002–1009. DOI: 10.1016/j.prp.2017.04.013 |

| [37] | Royal I, Lamarche-Vane N, Lamorte L, et al. Activation of cdc42, rac, PAK, and rho-kinase in response to hepatocyte growth factor differentially regulates epithelial cell colony spreading and dissociation. Mol Biol Cell, 2000, 11(5): 1709–1725. DOI: 10.1091/mbc.11.5.1709 |

| [38] | Kermorgant S, Aparicio T, Dessirier V, et al. Hepatocyte growth factor induces colonic cancer cell invasiveness via enhanced motility and protease overproduction. evidence for PI3 kinase and PKC involvement. Carcinogenesis, 2001, 22(7): 1035–1042. DOI: 10.1093/carcin/22.7.1035 |

| [39] | Simian M, Hirai Y, Navre M, et al. The interplay of matrix metalloproteinases, morphogens and growth factors is necessary for branching of mammary epithelial cells. Development, 2001, 128(16): 3117–3131. |

| [40] | Ma PC, Jagadeeswaran R, Jagadeesh S, et al. Functional expression and mutations of c-met and its therapeutic inhibition with SU11274 and small interfering RNA in non-small cell lung cancer. Cancer Res, 2005, 65(4): 1479–1488. DOI: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-2650 |

| [41] |

Xu XY, Chen P. Research progress on non-small-cell lung cancer drugs targeting Met.

Drugs Clin, 2016, 31(4): 562–566.

(in Chinese). 徐晓燕, 陈鹏. 作用于Met靶点的非小细胞肺癌治疗药物研究进展. 现代药物与临床, 2016, 31(4): 562-566. |

| [42] | Cappuzzo F, Marchetti A, Skokan M, et al. Increased MET gene copy number negatively affects survival of surgically resected non-small-cell lung cancer patients. J Clin Oncol, 2009, 27(10): 1667–1674. DOI: 10.1200/JCO.2008.19.1635 |

| [43] | Zhang N, Xie FB, Gao W, et al. Expression of hepatocyte growth factor and c-Met in non-small-cell lung cancer and association with lymphangiogenesis. Mol Med Rep, 2015, 11(4): 2797–2804. DOI: 10.3892/mmr.2014.3071 |

| [44] | Park S, Choi YL, Sung CO, et al. High MET copy number and MET overexpression: poor outcome in non-small cell lung cancer patients. Histol Histopathol, 2012, 27(2): 197–207. |

| [45] | Fioroni I, Dell'Aquila E, Pantano F, et al. Role of c-mesenchymal-epithelial transition pathway in gastric cancer. Expert Opin Pharmacother, 2015, 16(8): 1195–1207. DOI: 10.1517/14656566.2015.1037739 |

| [46] | Peng Z, Zhu Y, Wang QQ, et al. Prognostic significance of MET amplification and expression in gastric cancer: a systematic review with meta-analysis. PLoS ONE, 2014, 9(1): e84502. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0084502 |

| [47] |

Zhu XR, Zheng LZ. Research progress of HGF/c-Met-related targeted therapy of gastric cancer.

J Shanghai Jiaotong Univ: Med Sci, 2016, 36(1): 133–137.

(in Chinese). 朱雪茹, 郑磊贞. HGF/c-Met与胃癌靶向治疗的研究进展. 上海交通大学学报:医学版, 2016, 36(1): 133-137. |

| [48] | Fuse N, Kuboki Y, Kuwata T, et al. Prognostic impact of HER2, EGFR, and c-MET status on overall survival of advanced gastric cancer patients. Gastric Cancer, 2016, 19(1): 183–191. DOI: 10.1007/s10120-015-0471-6 |

| [49] | Zhao J, Zhang XX, Xin Y. Up-regulated expression of ezrin and c-Met proteins are related to the metastasis and prognosis of gastric carcinomas. Histol Histopathol, 2011, 26(9): 1111–1120. |

| [50] | Sotoudeh K, Hashemi F, Madjd Z, et al. The clinicopathologic association of c-MET overexpression in Iranian gastric carcinomas; an immunohistochemical study of tissue microarrays. Diagn Pathol, 2012, 7: 57. DOI: 10.1186/1746-1596-7-57 |

| [51] | Garouniatis A, Zizi-Sermpetzoglou A, Rizos S, et al. FAK, CD44v6, c-Met and EGFR in colorectal cancer parameters: tumour progression, metastasis, patient survival and receptor crosstalk. Int J Colorectal Dis, 2013, 28(1): 9–18. DOI: 10.1007/s00384-012-1520-9 |

| [52] | Inno A, di Salvatore M, Cenci T, et al. Is there a role for IGF1R and c-MET pathways in resistance to cetuximab in metastatic colorectal cancer?. Clin Colorectal Cancer, 2011, 10(4): 325–332. DOI: 10.1016/j.clcc.2011.03.028 |

| [53] | Qian LY, Li P, Li XR, et al. Multivariate analysis of molecular indicators for postoperative liver metastasis in colorectal cancer cases. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev, 2012, 13(8): 3967–3971. DOI: 10.7314/APJCP.2012.13.8.3967 |

| [54] |

Song WT, Sun YL. Role of hepatocyte growth factor receptor c-met regulating epithelial-mesenchymal transition in metastasis of colorectal cancer.

Cancer Res Prev Treat, 2015, 42(7): 737–739.

(in Chinese). 宋文韬, 孙燕来. 肝细胞生长因子受体c-met调控上皮间质转化在结直肠癌转移中的研究进展. 肿瘤防治研究, 2015, 42(7): 737-739. |

| [55] |

Cai YF, Su SY, Zhen ZJ. Relationship between c-met expression level and postoperative prognosis of hepatocellular carcinoma.

Chin J Gen Surg, 2013, 22(12): 1580–1584.

(in Chinese). 蔡云峰, 苏树英, 甄作均. 肝癌组织c-met表达与肝癌术后预后的关系. 中国普通外科杂志, 2013, 22(12): 1580-1584. |

| [56] |

Li YW, Liu HY, Chen J. Dysregulation of HGF/c-Met signal pathway and their targeting drugs in lung cancer.

Chin J Lung Cancer, 2014(8): 625–634.

(in Chinese). 李永文, 刘红雨, 陈军. 肺癌细胞中HGF/c-Met信号通路的异常调控及其靶向药物研究进展. 中国肺癌杂志, 2014(8): 625-634. DOI:10.3779/j.issn.1009-3419.2014.08.08 |

| [57] | Engelman JA, Zejnullahu K, Mitsudomi T, et al. MET amplification leads to gefitinib resistance in lung cancer by activating ERBB3 signaling. Science, 2007, 316(5827): 1039–1043. DOI: 10.1126/science.1141478 |

| [58] | Lengyel E, Sawada K, Salgia R. Tyrosine kinase mutations in human cancer. Curr Mol Med, 2007, 7(1): 77–84. DOI: 10.2174/156652407779940486 |

| [59] | 贾颖, 陈兴国. HGF/c-Met信号途径与肿瘤关系的研究进展. 山东医药, 2015, 55(41): 101-104. DOI:10.3969/j.issn.1002-266X.2015.41.042 |

| [60] | Lee JH, Han SU, Cho H, et al. A novel germ line juxtamembrane Met mutation in human gastric cancer. Oncogene, 2000, 19(43): 4947–4953. DOI: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203874 |

| [61] | de Aguirre I, Salvatierra A, Font A, et al. c-Met mutational analysis in the sema and juxtamembrane domains in small-cell-lung-cancer. Transl Oncogenomics, 2006, 1: 11–18. |

| [62] | Giordano S, Maffe A, Williams TA, et al. Different point mutations in the met oncogene elicit distinct biological properties. FASEB J, 2000, 14(2): 399–406. DOI: 10.1096/fasebj.14.2.399 |

| [63] | Waqar SN, Cottrell CE, Morgensztern D. MET mutation associated with responsiveness to crizotinib. J Thorac Oncol, 2015, 10(5): e29–e31. DOI: 10.1097/JTO.0000000000000478 |

| [64] | Krishnaswamy S, Kanteti R, Duke-Cohan JS, et al. Ethnic differences and functional analysis of MET mutations in lung cancer. Clin Cancer Res, 2009, 15(18): 5714–5723. DOI: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-0070 |

| [65] |

Yu W, Jiao N. Research Progress of HGF/c-Met Pathway and tumorigenesis.

Chin J Misdiagn, 2010, 10(23): 5565–5566.

(in Chinese). 俞维, 焦娜. HGF/c-Met信号通路与肿瘤的研究进展. 中国误诊学杂志, 2010, 10(23): 5565-5566. |

| [66] | Spina A, de Pasquale V, Cerulo G, et al. HGF/c-MET axis in tumor microenvironment and metastasis formation. Biomedicines, 2015, 3(1): 71–88. DOI: 10.3390/biomedicines3010071 |

| [67] | Danilkovitch-Miagkova A, Zbar B. Dysregulation of Met receptor tyrosine kinase activity in invasive tumors. J Clin Invest, 2002, 109(7): 863–867. DOI: 10.1172/JCI0215418 |

| [68] | Ruco L, Scarpino S. The pathogenetic role of the HGF/c-Met system in papillary carcinoma of the thyroid. Biomedicines, 2014, 2(4): 263–274. DOI: 10.3390/biomedicines2040263 |

| [69] | Petrelli A, Valabrega G. Multitarget drugs: the present and the future of cancer therapy. Expert Opin Pharmacother, 2009, 10(4): 589–600. DOI: 10.1517/14656560902781907 |

| [70] | Murray DW, Didier S, Chan A, et al. Guanine nucleotide exchange factor Dock7 mediates HGF-induced glioblastoma cell invasion via rac activation. Br J Cancer, 2014, 110(5): 1307–1315. DOI: 10.1038/bjc.2014.39 |

| [71] | Khirwadkar Y, Hiscox SE, Jordan NJ, et al. HGF/SF promotes an aggressive phenotype in c-Met-overexpressing fulvestrant-resistant MCF-7 cells-Evidence for MMP-9 and PI3k involvement. Ann Oncol, 2007, 18(S4): 611–617. |

| [72] |

Zong ZY, Li X, Han ZL, et al. Effect of tumor associated macrophages on the expression of c-Met in hepatocellular carcinoma cells.

J Shandong Univ: Health Sci, 2016, 54(3): 14–18.

(in Chinese). 宗兆运, 李霞, 韩振龙, 等. 肿瘤相关巨噬细胞对肝癌细胞c-Met分子表达的影响. 山东大学学报:医学版, 2016, 54(3): 14-18. |

| [73] |

Chen ZW, Peng S, Xu DG, et al. Immunosuppressive role of HGF/C-Met pathway in tongue squamous cell cancer to inhibit infiltration of CD1a+DC.

Chin J Oral Maxillofac Surg, 2015, 13(4): 329–334.

(in Chinese). 陈仲伟, 彭参, 徐冬贵, 等. 舌鳞癌微环境中HGF/C-Met信号通路对CD1a+DC的抑制作用. 中国口腔颌面外科杂志, 2015, 13(4): 329-334. |

| [74] | Lin A, Schildknecht A, Nguyen LT, et al. Dendritic cells integrate signals from the tumor microenvironment to modulate immunity and tumor growth. Immunol Lett, 2010, 127(2): 77–84. DOI: 10.1016/j.imlet.2009.09.003 |

| [75] |

Song SL, Bi MH. Research progress of HGF/MET signaling pathway in EGFR-TKI resistance in non-small cell lung cancer.

Chin J Lung Cancer, 2014, 17(10): 755–759.

(in Chinese). 宋世龙, 毕明宏. HGF/MET信号通路在非小细胞肺癌EGFR-TKI耐药性中的研究进展. 中国肺癌杂志, 2014, 17(10): 755-759. DOI:10.3779/j.issn.1009-3419.2014.10.08 |

| [76] | Yano S, Wang W, Li Q, et al. Hepatocyte growth factor induces gefitinib resistance of lung adenocarcinoma with epidermal growth factor receptor-activating mutations. Cancer Res, 2008, 68(22): 9479–9487. DOI: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-1643 |

| [77] | Zhen Q, Liu JF, Gao L, et al. MicroRNA-200a targets EGFR and c-Met to inhibit migration, invasion, and gefitinib resistance in non-small cell lung cancer. Cytogenet Genome Res, 2015, 146(1): 1–8. DOI: 10.1159/000434741 |

| [78] | Suman S, Kurisetty V, Das TP, et al. Activation of AKT signaling promotes epithelial-mesenchymal transition and tumor growth in colorectal cancer cells. Mol Carcinog, 2014, 53(Suppl): E151–E160. |

| [79] | Niemann HH. Structural basis of MET receptor dimerization by the bacterial invasion protein InlB and the HGF/SF splice variant NK1. Biochim Biophys Acta, 2013, 1834(10): 2195–2204. DOI: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2012.10.012 |

| [80] | Mizuno S, Nakamura T. HGF-MET cascade, a key target for inhibiting cancer metastasis: the impact of NK4 discovery on cancer biology and therapeutics. Int J Mol Sci, 2013, 14(1): 888–919. DOI: 10.3390/ijms14010888 |

| [81] |

Yan JJ, Liu J, Zhang SG, et al. C-met tyrosine kinase inhibitors: research advances.

J Int Pharm Res, 2012, 39(3): 184–191.

(in Chinese). 严家菊, 刘靖, 张首国, 等. 以c-met为靶点的酪氨酸激酶抑制剂的研究进展. 国际药学研究杂志, 2012, 39(3): 184-191. |

| [82] | Kishi Y, Kuba K, Nakamura T, et al. Systemic NK4 gene therapy inhibits tumor growth and metastasis of melanoma and lung carcinoma in syngeneic mouse tumor models. Cancer Sci, 2009, 100(7): 1351–1358. DOI: 10.1111/cas.2009.100.issue-7 |

| [83] | Suzuki Y, Sakai K, Ueki J, et al. Inhibition of Met/HGF receptor and angiogenesis by NK4 leads to suppression of tumor growth and migration in malignant pleural mesothelioma. Int J Cancer, 2010, 127(8): 1948–1957. DOI: 10.1002/ijc.25197 |

| [84] | Bahrami A, Shahidsales S, Khazaei M, et al. C-Met as a potential target for the treatment of gastrointestinal cancer: Current status and future perspectives. J Cell Physiol, 2017, 232(10): 2657–2673. DOI: 10.1002/jcp.v232.10 |

| [85] | Hori A, Kitahara O, Ito Y, et al. Monotherapeutic and combination antitumor activities of TAK-701, a humanized anti-hepatocyte growth factor neutralizing antibody, against multiple types of cancer. Cancer Res, 2009, 69(9): 18–22. |

| [86] | Spigel DR, Ervin TJ, Ramlau R, et al. Final efficacy results from OAM4558g, a randomized phase Ⅱ study evaluating MetMAb or placebo in combination with erlotinib in advanced NSCLC. J Clin Oncol, 2011, 29(S1): 7505. |

| [87] | Spigel DR, Edelman MJ, O'Byrne K, et al. Results from the phase Ⅲ randomized trial of onartuzumab plus erlotinib versus erlotinib in previously treated stage ⅢB or Ⅳ non-small-cell lung cancer: METLung. J Clin Oncol, 2017, 35(4): 412–420. DOI: 10.1200/JCO.2016.69.2160 |

| [88] | Daud A, Kluger HM, Kurzrock R, et al. Phase Ⅱ randomised discontinuation trial of the MET/VEGF receptor inhibitor cabozantinib in metastatic melanoma. Br J Cancer, 2017, 116(4): 432–440. DOI: 10.1038/bjc.2016.419 |

| [89] |

Li LL, Ai XJ. Research progress of small molecule inhibitor based on c-met kinase.

J Anhui Agric Sci, 2016, 44(13): 153–156.

(in Chinese). 李丽丽, 艾晓杰. 基于c-Met激酶的小分子抑制剂研究进展. 安徽农业科学, 2016, 44(13): 153-156. DOI:10.3969/j.issn.0517-6611.2016.13.050 |

| [90] | Cui JJ, Tran-Dubé M, Shen H, et al. Structure based drug design of crizotinib (PF-02341066), a potent and selective dual inhibitor of mesenchymal-epithelial transition factor (c-MET) kinase and anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK). J Med Chem, 2011, 54(18): 6342–6363. DOI: 10.1021/jm2007613 |

| [91] | You LK, Shou JW, Deng DC, et al. Crizotinib induces autophagy through inhibition of the STAT3 pathway in multiple lung cancer cell lines. Oncotarget, 2015, 6(37): 40268–40282. |

| [92] | Article T, Camidge DR, Bang Y, et al. Progression-free survival (PFS) from a phase Ⅰ study of crizotinib (PF-02341066) in patients with ALK-positive non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). J Clin Oncol, 2011, 29(15): 2501. |

| [93] |

Zhu HB, Xu XY, Wang L. Clinical research of crizotinib in advanced non-small cell lung cancer.

Chin J Lung Cancer, 2013, 16(6): 321–324.

(in Chinese). 朱海波, 徐小玉, 王玲. 克里唑替尼治疗晚期非小细胞肺癌的临床研究进展. 中国肺癌杂志, 2013, 16(6): 321-324. DOI:10.3779/j.issn.1009-3419.2013.06.09 |

| [94] | Crinò L, Kim D, Riely GJ, et al. Initial phase Ⅱ results with crizotinib in advanced ALK-positive non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC): PROFILE 1005. J Clin Oncol, 2011, 29(suppl): 7514. |

| [95] | Leprieur EG, Fallet V, Cadranel J, et al. Spotlight on crizotinib in the first-line treatment of ALK-positive advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: patients selection and perspectives. Lung Cancer (Auckl), 2016, 7: 83–89. |

2018, Vol. 34

2018, Vol. 34