中国科学院微生物研究所、中国微生物学会主办

文章信息

- 刘伟, 李立, 叶桦, 屠伟

- Liu Wei, Li Li, Ye Hua, Tu Wei

- 权重基因共表达网络分析在生物医学中的应用

- Weighted gene co-expression network analysis in biomedicine research

- 生物工程学报, 2017, 33(11): 1791-1801

- Chinese Journal of Biotechnology, 2017, 33(11): 1791-1801

- 10.13345/j.cjb.170006

-

文章历史

- Received: January 6, 2017

- Accepted: March 6, 2017

2 军事医学科学院 卫生勤务与医学情报研究所,北京 100850;

3 宁波市医疗中心李惠利医院 消化内科,浙江 宁波 315040;

4 德州A & M健康医学中心,美国 德州 77843-1114

2 Institute of Health Service and Medical Information, Academy of Military Medical Sciences, Beijing 100850, China;

3 Department of Gastroenterology, Ningbo Medical Treatment Center Lihuili Hospital, Ningbo 315040, Zhejiang, China;

4 Department of Molecular and Cellular Medicine, Texas A & M Health Sciences Center, 77843-1114, Texas, USA

随着高通量研究方法的出现和发展,系统地描述和分析这些高通量数据,筛选出重要信息是进行后续研究的基础。生物医学研究中各种组学数据的不断增多,使得从这些海量数据提取关键信息成为人们一项重要的研究课题。至今,由于人们对功能网络的忽视,单个分子研究仍然是人们关注的重点。但是癌症系统生物学的进展,使人们认识到功能网络在癌症的发生发展中的重要性。权重基因共表达网络分析(Weighted gene co-expression network analysis,WGCNA)方法基于表达模式类似的分子可能参与特定生物学功能的理论,最初由Zhang和Horvath[1]提出,因其强大的分析效能,在生物医学研究中得到广泛应用。本文主要对WGCNA在疾病、进化和临床医学研究中的应用进行综述。

1 WGCNA的原理和分析流程 1.1 原理WGCNA利用分子间的表达相关系数来衡量它们的共表达关系,同一模块中的分子表达模式相似,而和其他模块分子表达模式差别较大。表达模式相似的分子可能参与同一生物学过程或通路。因而,可将复杂的组学数据简化为若干个功能模块,这些模块和表型信息关联,可发现有生物学意义的模块。

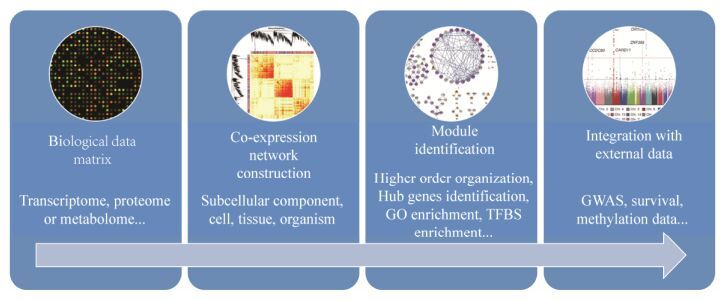

1.2 分析流程WGCNA分析转录组数据的流程大致如下(图 1)。首先,为了构建可信的基因共表达网络,基因表达谱数据应进行适当的数据归一化,保证样品间基因表达谱的可比性。第二,计算基因表达相关矩阵即所有基因之间两两相关系数,基因i和基因j的相关系数为sij=|cor(i, j)|,则基因表达相关矩阵为S=[sij]。通过幂指数aij=|sij|β加权将S转化为邻接矩阵(Adjacency matrix) A=[aij]。构建的网络不具方向性,A是非负对称矩阵,是所有后继分析的基础。第三,A被转换为拓扑矩阵Ω=[ωij],拓扑矩阵在生物学网络中很有用。1-ωij用来定义节点相异度(Dissimilarity),对节点相异度进行聚类分析来鉴定网络模块。然后,对模块内基因的连接度(Intramodular connectivity)进行计算,连接度高的基因可能是模块关键基因。最后,对模块或关键基因和外部信息进行关联,如临床信息,挖掘出有生物学意义的模块或关键基因。

|

| 图 1 WGCNA分析的流程图(根据文献[1]修改) Figure 1 The workflow for weighted gene co-expression network analysis (WGCNA). Kinds of matrix data even clinical data can be used as input for WGCNA. Then, pairwise correlation for each data point is calculated, which can be represented as a network of interest. Cluster analysis is used to identify modules within the network. The higher order organization of the modules can be identified. Module based analysis, such as hub gene discovery, gene ontology enrichment, transcription factor binding site enrichment, differential module expression, and gene function prediction using guilt-by-association can be performed. Finally, additional data such as GWAS data, SNP information, patient survival, and treatment response can be integrated to find biologically meaningful signals. |

| |

和非权重基因网络相比,WGCNA具有多种优点[2]。首先,它保留了网络节点连接度具有连续性的特性。非权重基因网络中2个节点间的关系是通过有或无来表示,导致信息丢失。其次,它具有强大的分析效能。非权重网络中2个节点间的关系受阀值选择影响。它还能被分解或近似为更简单的网络。网络参数间的关系可以很简单地表示出来。最后,标准的数据挖掘方法如聚类分析结果可以转化为权重网络。算法开发者认为最少要15个样本才适合此分析。

WGCNA的缺点是相关网络基于相关系数,必须整合其他数据如蛋白质-蛋白质相互作用和甲基化才能提供基因调控信息。样品异质性会影响模块鉴定,如果数据来自多个组织或多种条件,组织特异性/条件特异性模块信号可能会被稀释,导致无法有效鉴定。因而,要根据研究目的设计分析,如研究看家或者组织共享的模块时,可用不同组织来源的数据,而要寻找条件特异性模块,需用不同条件下的实验数据。组织中占少数比例的细胞其基因共表达信号可能受其他细胞掩盖,最好的方法就是使用细胞基因表达数据进行WGCNA。另外,不同的数据预处理和分析参数选择也会引起不同的结果,如不同的基因表达归一化方式、相关系数计算方式、聚类方法等。最后,样本数越多,得到的结果越好;但是,随着样本数和基因数目增多,需要更多的计算资源。

2 WGCNA在生物医学研究中的应用 2.1 WGCNA与疾病研究WGCNA被应用到疾病的机制、疾病分型和预后等研究中(表 1)。网络模块中的节点分子往往是模块功能发挥的关键分子,在疾病的发生发展中起重要作用。比如,Wang等[3]利用WGCNA和miRNA差异表达分析,发现在人前列腺癌中2个差异表达miRNA可能调控3个和细胞周期调控相关的关键节点基因。过表达验证实验表明这两个miRNA可以抑制细胞生长和促进凋亡。因此,细胞周期异常可能是导致恶性前列腺癌的一个分子通路。这些结果为恶性前列腺癌发病机制提供了重要线索。

| Studies | Samples | Methods | Research results |

| Gene networks and microRNAs implicated in aggressive prostate cancer | Lymphoblastoid cell lines derived from 62 aggressive and 63 nonaggressive prostate cancer patients | DNA microarray | miR-145 and miR-331-3p may target hub genes (cdca5 and kif23) and subsequently resulted in cell growth inhibition and apoptosis[3]. |

| Transcriptomic analysis of autistic brain reveals convergent molecular pathology | Superior temporal gyrus, prefrontal cortex, and cerebellar vermis of brain tissue from 19 autism and 17 controls | DNA microarray and RNA-Seq | Two modules associated with autism were identified: a neuronal module enriched for known autism susceptibility genes and a module enriched for immune genes and glial markers. Only neuronal module is enriched for autism GWAS signals, indicating non-genetic aetiology for immune module[7]. |

| Network organization of the huntingtin proteomic interactome in mammalian brain | Brain tissue protein from BACHD mice and wild-type mice | Affinity purification and LC-MS/MS | WGCNA was firstly applied to affinity-purification derived Huntingtin proteomic interactome. Htt-containing module is highly enriched with proteins involved in 14-3-3 signaling, microtubule-based transport, and proteostasis[8]. |

| WGCNA of multiorgan dysfunction syndrome after mechanical circulatory support therapy | Peripheral blood mononuclear cells from 29 patients | DNA microarray | WGCNA showed Sequential Organ Failure Assessment score was correlated with the black module whose hub genes includes defa1, defa3 and defa4, which are multifunctional mediators of innate and adaptive immunity. These results suggest potential biomarkers for immune response triggered by MCSD implantation[9]. |

| Two gene co-expression modules differentiate psychotics and controls | Brain samples from 50 schizophrenia, 50 bipolar disorder and 50 unaffected control subjects | DNA microarray | Both modules M1A enriched with neuron differentiation and neuron development genes and M3A enriched with genes related to metallothioneins changed in schizophrenia and bipolar disorder subjects, suggesting the common etiologies. Only M1A showed significant enrichment of GWAS signals, indicating aberrant M3A may be environmentally induced[10]. |

| WGCNA of glioma | 276 tumor samples of different glioma subtypes and grading | DNA microarray | A novel prognostic 185-gene signature linked to a proastrocytic pattern of tumor cell differentiation is associated with long survival. The correlation between kinase module and EGFR gene amplification suggested that EGF signaling in glioma may be regulated by Sprouty family proteins[4]. |

| Protein expression based multimarker analysis of breast cancer | Formalin-fixed, paraffin embedded breast tissue donor blocks | Tissue microarray | Three markers (P53, Na-KATPase-β1, and Tgf β receptor Ⅱ) can identify three groups of patients with low, moderate and high mortality rates. The three tumor markers can be used for predicting breast cancer survival outcomes[11]. |

| Quantitative electroencephalographic biomarkers for major depressive disorder | 121 subjects aged 21-70 with major depressive disorder and 37 normal patients | Quantitative electroencephalographic | Results suggests a loss of selectivity in resting functional connectivity in depressed patients. Differences in frontal alpha power and synchrony can be potential biomarker for the disease[12]. |

| Cross-species WGCNA of breast cancer metastatic susceptibility | Microarray datasets of 2 human breast cancer and 3 mouse metastasis model | DNA microarray | Gene membership of the networks is highly conserved within and between species. TPX2 module can predict distant metastasis-free survival in ER+ tumors. These results suggest that susceptibility to metastatic disease is cell-autonomous in ER- tumors and associated with the mitotic spindle checkpoint. While nontumor genetics and pathway activities-associated stromal biology are significant modifiers of the rate of metastatic spread of ER- tumors[5]. |

| Genetics of gene expression and its effect on disease | 1002 blood tissues and 673 adipose tissues | DNA microarray | Module MEMN, which enriched with immune response and macrophage-activating genes, is conserved in human and mouse. The module also is enriched for genes associated with obesity and obesity associated gene variants. Results provide functional support for disease eSNP[13]. |

| miRNA: microRNA; Cdca5: cell division cycle associated 5; Kif23: kinesin family member 23; EGFR: epidermal growth factor receptor; ER: estrogen receptor; Tpx2: targeting protein for Xk1p2; GWAS: genome-wide association study; BACHD: bacterial artificial chromosome expressing Huntington’s disease protein; LC-MS/MS: liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry/mass spectrometry; Htt: Huntingtin; WGCNA: weighted gene co-expression network analysis; Defa: defensin α; ATP1B1: ATPase, Na+/K+ transporting beta1; Tgfbr2: transforming growth factor receptor type2. | |||

肿瘤细胞基因组不稳定,具有异质性。即使组织病理学类似的肿瘤也可能有截然不同的预后。基于网络的转录组分析可以有效对复杂数据进行降维,系统描述肿瘤基因表达异质性,并进行肿瘤分型和预后。Ivliev等[4]对5个已发表的共790例胶质瘤转录组数据进行WGCNA分析,鉴定得到20个共同模块,模块则进一步形成更高级的组织结构,分别和间充质分化、增殖、前星形胶质细胞分化和神经元生成等亚型相关。该研究发现前星形胶质细胞特异的185个基因和病人长生存期相关,并可定义前神经元亚型。

人和小鼠疾病模型之间的转录组数据并不能直接进行比较。如何充分挖掘利用数据库中已有大量数据,发现动物模型和人类疾病之间的保守性和差异性,为科学合理使用动物模型研究人类疾病提供信息?传统的差异基因比较由于样本批次差异和统计分析方法差异,不同研究得到的基因标记物往往不同,并不能满足这种数据分析需求。WGCNA则克服了这些缺陷,可以为跨物种比较提供定性(模块成员)和定量(模块成员连接度)信息。Hu等[5]的研究表明,跨物种网络分析是鉴定肿瘤转移中关键生物学过程的有力工具。

为了克服不同研究结果间的不一致性,Giotti等[6]提取了4个不同正常和肿瘤细胞株中的细胞周期基因转录组数据,发现细胞周期模块在不同细胞间具有较大的保守性,其可分为G1/S-S和G2-M两个不同的模块。这表明整合不同数据集,对特定的亚转录组进行分析,也能获得有效信息。

2.2 WGCNA与正常组织研究正常组织功能的发挥依赖于不同类型的细胞、细胞器和不同分子间相互协调。对正常组织基因表达网络的研究有助于理解疾病发生的机制。WGCNA能够将高通量组学数据降维到数十个功能模块,通过研究模块间关系揭示正常状态下个体、组织或者细胞的功能网络组织图谱(表 2)。

| Studies | Samples | Methods | Research results |

| Functional organization of human brain transcriptome | Different brain regions from 160 subjects | DNA microarray | WGCNA identified modules of coexpressed genes that correspond to neurons, oligodendrocytes, astrocytes and microglia. Other modules corresponded to additional cell types, organelles, synaptic function, gender differences and the subventricular neurogenic niche. Subventricular zone astrocytes may have a distinct gene expression pattern relative to protoplasmic astrocytes[14]. |

| Sex-specific modulation of gene expression networks in murine hypothalamus | Hypothalamus from 89 mice | DNA microarray | Sex has the strongest effect on the expression of genes on the X and Y chromosomes. Genes associated with the endocrine system and neuropeptide signaling also differ significantly. In males the Y-linked gene, uty, is a hub gene in a module that regulates chromatin modification and gene transcription. In females, the X chromosome paralog, kdm6a, takes the place of uty in the same network[15]. |

| Aging effects on DNA methylation modules in human brain and blood tissue | Whole blood, leukocytes, and different brain regions, including cortex, pons, and cerebellum | DNA methylation microarray | WGCNA of 2442 DNA methylation arrays identified an age-related co-methylation module, which is involved in nervous system development and neurogenesis. Blood is a promising surrogate for brain tissue when studying the effects of age on DNA methylation profiles[16]. |

| WGCNA of transcriptional regulation in murine embryonic stem cells | Murine embryonic stem cells from two studies | DNA microarray | Two modules of pluripotency and differentiation were identified. The pluripotency module is enriched with genes related to DNA damage repair, mitochondrial function and transcriptional regulation. Mrpl15, msh6, nrf1, nup133, ppif, rbpj, sh3gl2, and zfp39 may have important roles in maintaining ES cell pluripotency and self-renewal. And found the significant relationships between module membership and epigenetic modifications (histone modifications and promoter CpG methylation status)[17]. |

| Genetic programs in human and mouse early embryos | Human and mouse early embryos | RNA-Seq | Developmental stages can be delineated concisely by co-expressed modules, indicating a sequential order of transcriptional changes in pathways of cell cycle, gene regulation, translation and metabolism. Cross species comparison revealed most modules conserved between human and mouse. Conserved hub genes may be driver in mammalian pre-implantation development[18]. |

| Systems genetic analysis of osteoblast-lineage cells | Bone tissues from 96 HMDP inbred strains | DNA microarray, GWAS and eQTL | Module M9 is associated with BMD. M9 hub genes, maged1 and pard6g, are novel regulators of osteoblast activity[19]. |

| WGCNA of CHO cells identifies transcriptional modules associated with growth and productivity | CHO cell lines from 295 conditions | DNA microarray | Six modules were identified, two of which is associated with productivity[20]. |

| Tomato metabolome WGCNA | Two varieties of tomato with six genotypes | NMR-based metabolomics | WGCNA firstly applied to tomato metabolome, three modules associated with ripening traits were identified[21]. |

| Mrpl15: mitochondrial ribosomal protein L15; Msh6: mutS homolog 6; Nrf1: nuclear respiratory factor 1; Nup133: nucleoporin 133 kDa; Ppif: peptidylprolyl Isomerase F; RbpJ: recombination signal binding protein for immunoglobulin kappa J region; Sh3gl2: SH3-domain GRB2-like 2; Zfp39: zinc finger protein 39; HMDP: hybrid mouse diversity panel; GWAS: genome-wide association study; eQTL: expression quantitative trait loci; CHO: Chinese hamster ovary; MAGED1: melanoma antigen family D, 1; Wnt: wingless-type MMTV integration site family; Sfrp1: secreted frizzled-related protein 1; uty: ubiquitously transcribed tetratricopeptide repeat gene, Y-linked; Kdm6a: lysine (K)-specific demethylase 6A; NMR: nuclear magnetic resonance. | |||

理解药物对人体的作用及这些影响在模式生物中的重现是药理学研究的重要内容之一。Fortney等[22]对药物-药物相似性矩阵进行WGCNA分析,将具有类似作用模式的药物归为模块,通过这些模块可以预测已知药物的新功能。Iskar等[23]对经药物处理的人细胞株和大鼠肝脏的转录组数据进行WGCNA分析,发现70%的模块是各种细胞株共有的,15%的模块在人体外和大鼠体内是保守的。他们以此为基础进一步验证基因功能,并研究已有药物的作用新机制,为药物重定位(Drug repositioning)提供线索,如新的细胞周期抑制物、α-肾上腺素能受体、过氧化物酶体增殖物激活受体和雌激素受体调节剂。鉴定到的模块揭示了药物作用在不同细胞株和物种间的保守性,改进了人们对药物作用机制的理解。Delahaye-Duriez等[24]利用WGCNA发现癫痫病人共有的关键基因共表达模块M30,结合药物作用数据库Connectivity Map,挖掘出丙戊酸可以下调M30表达,是有效治疗癫痫的候选药物。

2.4 WGCNA与进化研究为更全面系统地表征人和小鼠间基因表达差异,Miller等[25]利用WGCNA对1 066多例大脑芯片数据进行分析,发现人和小鼠间脑基因表达网络总体上是保守的。小鼠中所有共表达的基因模块在人脑中也得到鉴定。当然,在人脑中鉴定到了人类特异的模块,包括和老年痴呆症发展相关的小胶质细胞模块,该模块中富集了神经退行性疾病基因。该研究发现了人和小鼠脑基因表达的保守性和差异性,为人类脑病小鼠模型应用研究提供思路。Oldham等[26]利用基因连接度对人和猩猩进行比较,发现大脑皮层不如皮层下区域保守。Filteau等[27]对湖白鱼回交后代的肌肉和脑组织的基因表达进行WGCNA分析,鉴定到在底栖和湖沼生态型生态化过程中适应性性状相关的模块;骨形态发生蛋白和钙信号是参与营养行为、营养形态(鳃耙)和繁殖协同进化的共有通路;血红蛋白和组成型应激蛋白(Hsp70)调控着湖白鱼的生长。在植物中,Buckberry等[28]比较了二倍体和异源多倍体棉花种子的基因共表达网络,发现二者不只是基因表达谱不同,共表达网络的拓扑结构也有差异,提示转录组结构在驯化过程中发挥作用。

2.5 WGCNA与基因功能注释很多物种的基因组注释程度有限,特别是功能注释。整合多个基因表达数据集,构建基因共表达网络,能发现无功能注释信息基因的潜在功能[29]。Stanley等[30]分析来自不同鸡组织和实验条件的1 043个芯片数据,共鉴定到15个模块,10个模块具有特定生物学过程的富集。类似的,Childs等[31]分析了大规模水稻转录组数据,共鉴定到71个共表达模块,并对水稻部分功能未知基因进行功能注释。这些研究表明基因共表达网络可以为基因组注释不全的物种提供功能信息。Walley等[32]利用WGCNA构建了玉米各发育阶段基因表达和调控网络,并和蛋白质组共表达网络比较,发现二者的重叠率不高,也就是二者具有一定互补性,因此整合mRNA、蛋白质和磷酸化蛋白质数据可以改进基因调控网络的预测效能。

3 展望随着全基因组水平检测技术,如GWAS、表观遗传学、第二代测序技术、高精度高通量质谱仪和代谢组学等的发展,检测成本不断降低,海量组学数据不断增多,传统的数据分析方法不能满足分析需求。生物学过程并非简单的通路或单个分子的加和,而是多层次的具有高度组织结构的分子网络。绘制网络的拓扑结构对理解生物学过程非常重要,并有助于理解疾病发生机制、评估疾病风险和进行疾病干预与治疗[33]。WGCNA自问世以来一直在优化和更新,在多个研究领域得到了广泛的应用。有人将其应用到脑不同区域脑电图数据的分析,将复杂的图像数据转化为较为清晰简洁的网络,以发现新的生物标记物[12]。此外,基因组水平的数据很复杂,WGCNA能对数据进行降维,将其简化为若干个模块。因此,基因模块相关性研究(Gene module association study,GMAS)可以补充GWAS结果[34],它通过研究多个基因如何以模块形式一起发挥作用来帮助理解复杂疾病。GMAS首先检测同一物种不同遗传背景个体的表型;利用基因表达谱数据构建基因共表达网络;上万个基因降维到十几个模块,将模块和表型关联,而GWAS中是将SNPs和表型关联。GMAS的目标就是寻找共表达基因来解释复杂性状。此外,Iancu等[35]首次将WGCNA应用于RNA-Seq数据,Shirasaki等[8]首次将其应用于蛋白质组数据,Yepes等[36]用其分析胃癌miRNA表达数据。我们也构建了肿瘤细胞株的基因共表达网络,鉴定出的模块在肿瘤组织中具有保守性,能将病人分为预后好坏的2类[37]。随着单细胞测序技术的发展普及,WGCNA也将在单细胞转录组数据分析中发挥作用[38]。甚至有人将其应用于大气PM2.5的分析[39]。可以预见,WGCNA在生物医学及相关数据分析中的应用将越来越广泛。

| [1] | Zhang B, Horvath S. A general framework for weighted gene co-expression network analysis. Stat Appl Genet Mol Biol, 2005, 4(1): 17. |

| [2] | Horvath S. Weighted Network Analysis: Applications in Genomics and Systems Biology. New York: Springer, 2011. |

| [3] | Wang L, Tang H, Thayanithy V, et al. Gene networks and microRNAs implicated in aggressive prostate cancer. Cancer Res, 2009, 69(24): 9490–9497. DOI: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-2183 |

| [4] | Ivliev AE, ׳t Hoen PAC, Sergeeva MG. Coexpression network analysis identifies transcriptional modules related to proastrocytic differentiation and sprouty signaling in glioma. Cancer Res, 2010, 70(24): 10060–10070. DOI: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-2465 |

| [5] | Hu Y, Wu G, Rusch M, et al. Integrated cross-species transcriptional network analysis of metastatic susceptibility. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA, 2012, 109(8): 3184–3189. DOI: 10.1073/pnas.1117872109 |

| [6] | Giotti B, Joshi A, Freeman TC. Meta-analysis reveals conserved cell cycle transcriptional network across multiple human cell types. BMC Genomics, 2017, 18: 30. DOI: 10.1186/s12864-016-3435-2 |

| [7] | Voineagu I, Wang XC, Johnston P, et al. Transcriptomic analysis of autistic brain reveals convergent molecular pathology. Nature, 2011, 474(7351): 380–384. DOI: 10.1038/nature10110 |

| [8] | Shirasaki DI, Greiner ER, Al-Ramahi I, et al. Network organization of the huntingtin proteomic interactome in mammalian brain. Neuron, 2012, 75(1): 41–57. DOI: 10.1016/j.neuron.2012.05.024 |

| [9] | Wisniewski N, Cadeiras M, Bondar G, et al. Weighted gene coexpression network analysis (WGCNA) modeling of multiorgan dysfunction syndrome after mechanical circulatory support therapy. J Heart Lung Transpl, 2013, 32(4): S223. |

| [10] | Chen C, Cheng L, Grennan K, et al. Two gene co-expression modules differentiate psychotics and controls. Mol Psych, 2013, 18(12): 1308–1314. DOI: 10.1038/mp.2012.146 |

| [11] | Presson AP, Yoon NK, Bagryanova L, et al. Protein expression based multimarker analysis of breast cancer samples. BMC Cancer, 2011, 11: 230. DOI: 10.1186/1471-2407-11-230 |

| [12] | Leuchter AF, Cook IA, Hunter AM, et al. Resting-state quantitative electroencephalography reveals increased neurophysiologic connectivity in depression. PLoS ONE, 2012, 7(2): e32508. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0032508 |

| [13] | Emilsson V, Thorleifsson G, Zhang B, et al. Genetics of gene expression and its effect on disease. Nature, 2008, 452(7186): 423–428. DOI: 10.1038/nature06758 |

| [14] | Oldham MC, Konopka G, Iwamoto K, et al. Functional organization of the transcriptome in human brain. Nat Neurosci, 2008, 11(11): 1271–1282. DOI: 10.1038/nn.2207 |

| [15] | Mozhui K, Lu L, Armstrong WE, et al. Sex-specific modulation of gene expression networks in murine hypothalamus. Front Neurosci, 2012, 6: 63. |

| [16] | Horvath S, Zhang YF, Langfelder P, et al. Aging effects on DNA methylation modules in human brain and blood tissue. Genome Biol, 2012, 13(10): R97. DOI: 10.1186/gb-2012-13-10-r97 |

| [17] | Mason MJ, Fan GP, Plath K, et al. Signed weighted gene co-expression network analysis of transcriptional regulation in murine embryonic stem cells. BMC Genomics, 2009, 10: 327. DOI: 10.1186/1471-2164-10-327 |

| [18] | Xue ZG, Huang K, Cai CC, et al. Genetic programs in human and mouse early embryos revealed by single-cell RNA sequencing. Nature, 2013, 500(7464): 593–597. DOI: 10.1038/nature12364 |

| [19] | Calabrese G, Bennett BJ, Orozco L, et al. Systems genetic analysis of osteoblast-lineage cells. PLoS Genet, 2012, 8(12): e1003150. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003150 |

| [20] | Clarke C, Doolan P, Barron N, et al. Large scale microarray profiling and coexpression network analysis of CHO cells identifies transcriptional modules associated with growth and productivity. J Biotechnol, 2011, 155(3): 350–359. DOI: 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2011.07.011 |

| [21] | DiLeo MV, Strahan GD, den Bakker M, et al. Weighted correlation network analysis (WGCNA) applied to the tomato fruit metabolome. PLoS ONE, 2011, 6(10): e26683. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0026683 |

| [22] | Fortney K, Xie W, Kotlyar M, et al. NetwoRx: connecting drugs to networks and phenotypes in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Nucleic Acids Res, 2013, 41(D1): D720–D727. |

| [23] | Iskar M, Zeller G, Blattmann P, et al. Characterization of drug-induced transcriptional modules: towards drug repositioning and functional understanding. Mol Syst Biol, 2013, 9(1): 662. |

| [24] | Delahaye-Duriez A, Srivastava P, Shkura K, et al. Rare and common epilepsies converge on a shared gene regulatory network providing opportunities for novel antiepileptic drug discovery. Genome Biol, 2016, 17: 245. DOI: 10.1186/s13059-016-1097-7 |

| [25] | Miller JA, Horvath S, Geschwind DH. Divergence of human and mouse brain transcriptome highlights Alzheimer disease pathways. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA, 2010, 107(28): 12698–12703. DOI: 10.1073/pnas.0914257107 |

| [26] | Oldham MC, Horvath S, Geschwind DH. Conservation and evolution of gene coexpression networks in human and chimpanzee brains. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA, 2006, 103(47): 17973–17978. DOI: 10.1073/pnas.0605938103 |

| [27] | Filteau M, Pavey SA, St-Cyr J, et al. Gene coexpression networks reveal key drivers of phenotypic divergence in lake whitefish. Mol Biol Evol, 2013, 30(6): 1384–1396. DOI: 10.1093/molbev/mst053 |

| [28] | Hu GJ, Hovav R, Grover CE, et al. Evolutionary conservation and divergence of gene coexpression networks in gossypium (cotton) seeds. Genome Biol Evol, 2016, 8(12): 3765–3783. |

| [29] | López-Kleine L, Leal L, López C. Biostatistical approaches for the reconstruction of gene co-expression networks based on transcriptomic data. Brief Funct Genomics, 2013, 12(5): 457–467. DOI: 10.1093/bfgp/elt003 |

| [30] | Stanley D, Watson-Haigh NS, Cowled CJ, et al. Genetic architecture of gene expression in the chicken. BMC Genomics, 2013, 14: 13. DOI: 10.1186/1471-2164-14-13 |

| [31] | Childs KL, Davidson RM, Buell CR. Gene coexpression network analysis as a source of functional annotation for rice genes. PLoS ONE, 2011, 6(7): e22196. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0022196 |

| [32] | Walley JW, Sartor RC, Shen ZX, et al. Integration of omic networks in a developmental atlas of maize. Science, 2016, 353(6301): 814–818. DOI: 10.1126/science.aag1125 |

| [33] | Schadt EE, Björkegren JL. NEW: network-enabled wisdom in biology, medicine, and health care. Sci Transl Med, 2012, 4(115): 115rv1. |

| [34] | Weiss JN, Karma A, MacLellan WR, et al. "Good enough solutions" and the genetics of complex diseases. Circul Res, 2012, 111(4): 493–504. DOI: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.112.269084 |

| [35] | Iancu OD, Kawane S, Bottomly D, et al. Utilizing RNA-Seq data for de novo coexpression network inference. Bioinformatics, 2012, 28(12): 1592–1597. DOI: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bts245 |

| [36] | Yepes S, López R, Andrade RE, et al. Co-expressed miRNAs in gastric adenocarcinoma. Genomics, 2016, 108(2): 93–101. DOI: 10.1016/j.ygeno.2016.07.002 |

| [37] | Liu W, Li L, Li WD. Gene co-expression analysis identifies common modules related to prognosis and drug resistance in cancer cell lines. Int J Cancer, 2014, 135(12): 2795–2803. DOI: 10.1002/ijc.v135.12 |

| [38] | Poulin JF, Tasic B, Hjerling-Leffler J, et al. Disentangling neural cell diversity using single-cell transcriptomics. Nat Neurosci, 2016, 19(9): 1131–1141. DOI: 10.1038/nn.4366 |

| [39] | Yan SM, Wu G. Network analysis of fine particulate matter (PM2.5) emissions in China. Sci Rep, 2016, 6: 33227. DOI: 10.1038/srep33227 |

2017, Vol. 33

2017, Vol. 33