中国科学院微生物研究所,中国微生物学会,中国菌物学会

文章信息

- 林钰, 刘荣华, 周顺, 朱晓雨, 王金燕, 张晓华. 2021

- Yu Lin, Ronghua Liu, Shun Zhou, Xiaoyu Zhu, Jinyan Wang, Xiaohua Zhang. 2021

- 马里亚纳海沟沉积物可培养异养细菌的多样性及其DMSP降解能力

- Diversity of culturable heterotrophic bacteria from sediments of the Mariana Trench and their ability to degrade dimethylsulfoniopropionate (DMSP)

- 微生物学报, 61(4): 828-844

- Acta Microbiologica Sinica, 61(4): 828-844

-

文章历史

- 收稿日期:2020-10-30

- 修回日期:2020-12-30

- 网络出版日期:2021-01-11

2. 青岛海洋科学与技术试点国家实验室, 海洋生态与环境科学功能实验室, 山东 青岛 266071;

3. 中国海洋大学深海圈层与地球系统前沿科学中心, 山东 青岛 266100

2. Qingdao National Laboratory for Marine Science and Technology, Laboratory for Marine Ecology and Environmental Science, Qingdao 266071, Shandong Province, China;

3. Center for Advanced Science of Deep-Sea Spheres and Earth Systems, Ocean University of China, Qingdao 266100, Shandong Province, China

海洋沉积物覆盖地球表面的三分之二以上,蕴藏着数量庞大、种类丰富的微生物资源,并扮演着重要的生态角色[1]。马里亚纳海沟是地球上最深的海沟,位于北太平洋西部,菲律宾东北部马里亚纳群岛附近[2-3],海沟底部具有超高静水压力、低温和黑暗等特点。由于取样困难,早期从马里亚纳海沟中分离培养出的微生物较少。随着深海采样技术的发展,研究者对马里亚纳海沟微生物的研究逐渐得以开展。1976年,Morita等[4]首次从马里亚纳海沟沉积物中分离培养出第一株细菌——耐压假单胞菌(Pseudomonas bathycetes)。之后Takami等[5]对马里亚纳海沟10897 m沉积物中微生物进行分离培养,发现可培养微生物群落主要由真菌、放线菌和非嗜极菌以及多种嗜极菌(嗜碱菌、嗜热菌和嗜冷菌)组成,说明其中的微生物多样性并不因环境恶劣而单一。近年来,多个学者通过16S rRNA基因高通量测序技术[6-9]以及宏基因组测序技术[10]对马里亚纳海沟不同水层微生物的群落结构进行了探索,但免培养技术无法准确了解微生物的生理代谢特性和生态功能等。可培养技术对于全面了解微生物的生理、生化和代谢活动及认识微生物在复杂的生物地球化学循环中的作用是十分必要的,也是进行微生物资源开发和应用的重要基础。然而,依靠传统培养方法获得的微生物不到海洋环境中微生物总量的1%[11-12],迄今对马里亚纳海沟可培养微生物的研究报道依然很少[13],缺乏在不同实验条件下(如多种培养基、多种温度、不同采样深度等)对海沟沉积物微生物的规模化分离培养。

二甲基巯基丙酸内盐(dimethylsulphoniopropionate,DMSP)是海洋环境广泛分布的溶解态还原硫分子,也是地球上最丰富的有机硫分子之一[14],年产量约为2.0 pg[15],在海洋硫循环中发挥重要作用。DMSP可作为碳源和硫源,被微生物分解利用。DMSP裂解产生的二甲基硫(dimethyl sulfide,DMS)气体,是海气交换中硫元素的最主要存在形式[16]。DMS可与二甲基亚砜(dimethyl sulfoxide,DMSO)相互转化,两者皆可促进大气云凝结核的形成,从而直接影响全球云量,云量的增加可以增加地球对太阳辐射的反照率,从而降低地表温度,减缓温室效应,起到“冷室气体”的效果[17-19]。海洋生物合成的DMSP释放到自然环境中后成溶解态,不经酶促反应的半衰期为8年左右,速度极其缓慢。虽然海洋真核和原核生物均可降解DMSP,但异养细菌才是DMSP最主要的降解者[20]。目前已报道的细菌降解DMSP的主要途径有脱甲基途径和裂解途径[20-22]。其中脱甲基途径占据DMSP生物降解总量的70%左右,该途径可将DMSP降解生成活性气体甲硫醇(methanethiol,MeSH)[23]。裂解途径虽仅占DMSP生物降解总量的30%左右,但DMSP裂解产生丙烯酸盐时伴有“冷室气体” DMS的产生,因此具有更重要的生态意义。目前尚未见马里亚纳海沟DMSP降解菌多样性的报道,本研究为发掘DMSP降解新通路提供了新型菌株。

本文拟采用5种不同的异养菌培养基和3个不同的培养温度,对马里亚纳海沟5个站位的沉积物微生物进行规模化分离培养,基于16S rRNA基因测序鉴定其分类地位,并进一步选取代表性异养细菌进行DMSP降解能力测定。研究结果将为阐明深渊微生物的生命过程提供独特的微生物资源库。

1 材料和方法 1.1 样品采集本研究选用的深海沉积物样品采自2018年9月马里亚纳海沟综合地质地球物理调查共享航次,由“科学”号科考船采集。从本航次所有站位中选取5个站位(G18-1、G18-8、G18-9、ORH1-3和ORH1-9)进行样品采集,站位具体信息如表 1所示。

| Station | Longitude | Latitude | Depth/m | Sample collection section | Color and texture |

| G18-1 | 150°01′54.911″ | 13°59′58.224″ | 6300 | Sediment in the middle of the gravity column (143 cm) | Tan slime |

| G18-9 | 150°25′54.501″ | 15°12′30.373″ | 5800 | Sediment at the bottom of the gravity column (470 cm) | Brown slime |

| G18-8 | 149°30′35.981″ | 17°44′59.269″ | 5381 | Sediments on the surface of the gravity column (0 cm) | Yellow slime |

| ORH1-3 | 148°44′37.054″ | 17°50′58.432″ | 5802 | Sediments on the surface of the gravity column (0 cm) | Tan slime |

| ORH1-9 | 148°46′18.822″ | 17°50′56.616″ | 5794 | Sediment at the bottom of the gravity column (370 cm) | Brown slime |

1.2 培养基

本研究采用5种不同的培养基对马里亚纳海沟沉积物异养细菌进行分离培养。3种常规异养菌培养基2216E、R2A和TCBS培养基参照《海洋微生物学》(第二版)[24]配制。碱性蛋白胨水(alkaline peptone water,AP)培养基:称取AP (青岛海博生物) 20 g,加热搅拌溶解于1000 mL蒸馏水中,121 ℃高压灭菌15 min。TCBS肉汤培养基:称取TCBS琼脂(青岛海博生物) 74 g,煮沸溶解于1000 mL蒸馏水中,无需高压灭菌。另外,本研究采用DMSP终浓度为1 mmol/L的MBM (盐度35 PSU)培养基[25]对马里亚纳海沟沉积物异养细菌进行DMSP降解能力检测。

1.3 细菌的培养及分离纯化分别称取5个站位的沉积物样品约0.02 g于2 mL EP管中,加入1 mL无菌生理盐水(0.85%,W/V)作为原液,依次稀释成10-1、10-2、10-3浓度梯度。取不同稀释梯度的样品稀释液150 μL,用无菌涂布棒分别涂布至2216E、R2A和TCBS培养基上,每种培养基每个稀释度设置2个平行,分别置于4 ℃、16 ℃和28 ℃恒温培养箱中进行培养,培养时间为1个月(航行期间),回实验室后挑取单菌落,采用三区划线法接种于对应的新鲜培养基上进行细菌的分离纯化。称取0.05 g沉积物样品分别置于50 mL AP培养基和TCBS肉汤培养基中进行富集培养,每个站位每种培养基每个温度设置2个平行,分别于16 ℃和28 ℃ (G18-1为4 ℃和28 ℃)下进行富集培养,后续分离纯化方法如前文所述。

1.4 细菌16S rRNA基因测序鉴定 1.4.1 细菌基因组DNA提取和16S rRNA基因序列扩增:采用煮沸法并辅以酚-氯仿法[26]进行细菌基因组DNA提取。使用通用引物B8F (5′-AGA GTTTGATCCTGGCTCAG-3′)和B1510R (5′-GGT TACCTTGTTACGACTT-3′)[27],以提取的细菌DNA为模板,进行16S rRNA基因扩增,PCR扩增体系和反应条件参照Du等的方法[28]。将扩增成功的16S rRNA基因用限制性核酸内切酶BamH Ⅰ和Hae Ⅲ进行双酶切,选取酶切图谱不同的PCR产物送至青岛华大基因有限公司进行单端测序。

1.4.2 16S rRNA基因序列比对与系统进化树构建:采用Chromas软件对测序得到的DNA峰图进行查看和编辑,将得到的16S rRNA基因单端序列(长约650 bp) 提交至微生物标准数据库EzBioCloud (http://www.ezbiocloud.net/)进行BLAST同源性序列比对(比对时间2020年9月),得到菌株最相似种属及相似度并确定其分类地位。采用MAFFT version 7 (https://mafft.cbrc.jp/alignment/server/)、Gblocks Server (http://molevol.cmima.csic.es/castresana/Gblocks_server.html)及Mega-X邻接法(Neighbor-joining algorithm)构建系统进化树,并用网站iTOL (https://itol.embl.de/login.cgi)进一步完善美化进化树。另外,将所获取菌株的16S rRNA序列上传至GenBank数据库,登录号为MT974313、MT974314以及MW111123-MW111266。

1.5 菌株DMSP降解能力测定将海沟沉积物代表性菌株活化后接种于5 mL 2216E液体培养基中,在28 ℃以170 r/min振荡培养约24 h至菌液混浊。用紫外分光光度计测量其OD600值,用无菌MBM母液将菌体洗涤3次,并用MBM培养基将菌液的OD600值调为0.3。将调好OD值的菌液以1︰10比例加入200 μL含有终浓度为1 mmol/L DMSP的MBM培养基中,于28 ℃以170 r/min密封避光振荡培养30 h。利用气相色谱仪定量测定总体系中产生的DMS。采用可降解DMSP产生DMS的菌株Labrenzia aggregate LZB033[29]为阳性对照,不能降解DMSP的菌株Pelagibaca bermudensis LZD001为阴性对照,同时设置不加菌液、终浓度为1 mmol/L DMSP的MBM混合培养液为空白对照。菌株对DMSP的降解量以DMSP标准品碱解成DMS的峰面积与DMSP物质的量浓度关系的标准曲线进行换算。标准曲线采用梯度浓度DMSP标准溶液经碱解生成DMS制作(公式1)。

|

公式(1) |

其中,R2=0.9952。细菌破碎后采用Bradford法测定胞内蛋白质浓度。通过蛋白质浓度与吸光度之间关系的标准曲线(公式2),计算出胞内蛋白浓度。

|

公式(2) |

其中,R2=0.9914。最终菌株的DMSP降解能力以nmol DMS/(mg protein·h)为单位表示。

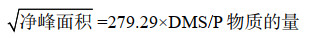

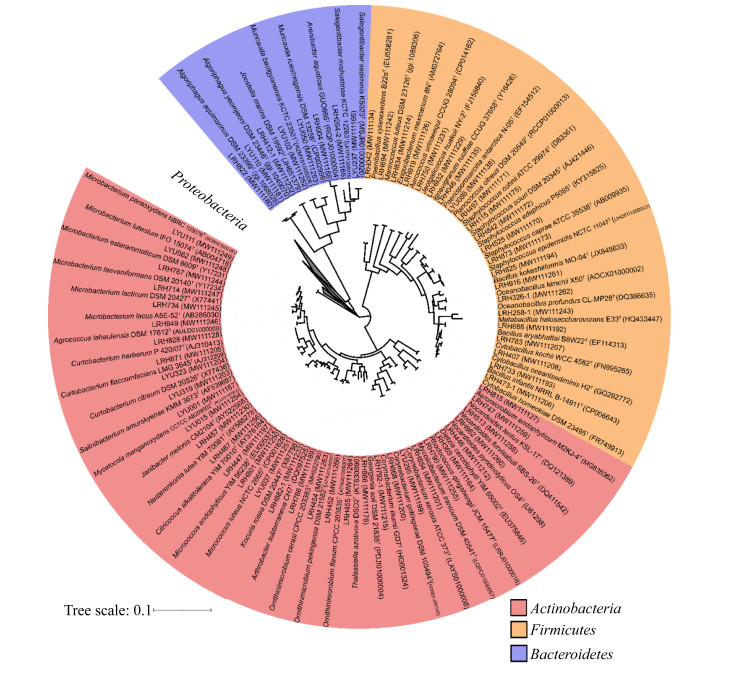

2 结果和分析 2.1 马里亚纳海沟沉积物可培养异养细菌的多样性本文对马里亚纳海沟5个站位的沉积物样品进行了微生物的分离培养,共获得1057株细菌。细菌16S rRNA基因测序结果表明,这些细菌分属于4门、7纲、22目、42科、76属和170种。4个门分别是变形菌门(Proteobacteria,815株)、放线菌门(Actinobacteria,135株)、厚壁菌门(Firmicutes,70株)和拟杆菌门(Bacteroidetes,37株),分别占总分离菌株的77.1%、12.8%、6.6%和3.5%。变形菌门主要由γ-变形菌纲(Gammaproteobacteria)和α-变形菌纲(Alphaproteobacteria)组成(图 1)。在纲水平,γ-变形菌纲(649株)占绝对优势,占总菌株数的61.4%;其次为α-变形菌纲(159株;15.0%)、放线菌纲(Actinobacteria,135株;12.8%)、芽孢杆菌纲(Bacilli,70株;6.6%)和黄杆菌纲(Flavobacteriia,26株;2.5%);另外2个纲,噬纤维菌纲(Cytophagia)仅包含11株,β-变形菌纲(Betaproteobacteria)仅包含7株。其中,γ-变形菌纲(16属)、α-变形菌纲(18属)、放线菌纲(22属)、芽孢杆菌纲(14属)和黄杆菌纲(4属)包含多种不同的属,而β-变形菌纲和噬纤维菌纲仅有1个属。在属水平,γ-变形菌纲的假单胞菌属(Pseudomonas)菌株最多,共分离出186株,分属于16个物种,占细菌分离总数的17.6%;γ-变形菌纲的盐单胞菌属(Halomonas)为第2大优势属,共分离出115株菌,分属于11个物种,占细菌分离总数的10.9%。另外,海杆菌属(Marinobacter)和假海源菌属(Pseudidiomarina)获得的菌株数目也比较多,分别获得8种87株菌和5种84株菌,交替单胞菌属(Alteromonas)也获得了4种63株菌。其他一些属,即包括Arenibacter和Salinicola在内的19属,仅分离培养出1株。以上研究结果表明马里亚纳海沟沉积物可培养微生物有丰富的多样性(图 1,2)。

|

| 图 1 马里亚纳海沟沉积物变形菌门可培养异养细菌与参考菌株的系统发育树 Figure 1 Neighbor-joining phylogenetic tree of Proteobacteria cultivable heterotrophic bacteria isolated from sediments of the Mariana Trench and their closest relatives based on 16S rRNA gene sequences. The serial number in parentheses denotes the GenBank accession number of the strain. The nucleotide substitution rate was 0.1. |

|

| 图 2 马里亚纳海沟沉积物可培养异养细菌与参考菌株的系统发育树 Figure 2 Neighbor-joining phylogenetic tree of representative cultivable heterotrophic bacteria isolated from sediments of the Mariana Trench and their closest relatives based on 16S rRNA gene sequences. The serial number in parentheses denotes the GenBank accession number of the strain. The nucleotide substitution rate was 0.1. |

2.2 不同深度沉积物中可培养异养细菌多样性

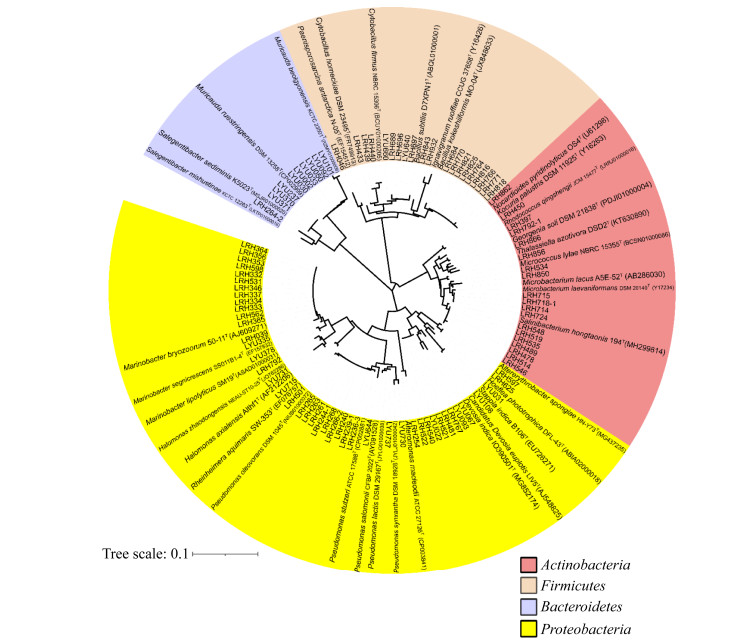

在海沟沉积物不同取样深度,可培养细菌的多样性存在明显差异。从表层沉积物(0 cm)和深层沉积物(143-470 cm)中分别分离培养出556株和501株细菌。在门水平,变形菌门占表层沉积物总分离菌株的比例(89.4%)高于深层沉积物(63.5%)。与之相反,放线菌门、拟杆菌门和厚壁菌门在深层沉积物的相对丰度高于表层(图 3-A)。在纲水平,γ-变形菌纲是海沟沉积物中最丰富的一类,其相对丰度表层(82.9%)高于深层(37.5%)。海沟沉积物可培养细菌的第二大优势类群α-变形菌纲在深层(25%)的比例高于表层(6.1%),同样,放线菌和芽孢杆菌深层比例均高于表层。黄杆菌纲、噬纤维菌纲和β-变形菌纲在海沟沉积物中丰度较小,这3种类群在深层比例更高(图 3-B)。在属水平,沉积物底层(62属)可培养细菌多样性高于沉积物表层(45属)。沉积物最丰富的属为假单胞菌属(182株),其在沉积物表层和深层的相对丰度都较高,但表层(22.7%)高于深层(11.2%)。沉积物中第2-5大优势属盐单胞菌属(115株)、海杆菌属(87株)、假海源菌属(84株)以及交替单胞菌属(49株)均是表层的相对丰度更高。其中,假海源菌属仅有8株在沉积物深层被分到。红球菌属(Rhodococcus)大部分在深层被分到,仅有几株在表层被分到。白色红杆菌属(Albirhodobacter)和短波单胞菌属(Brevundimonas)仅在深层被分离到,与之相反,希瓦氏菌属(Shewanella)仅在沉积物表层被分离到(图 3-C)。

|

| 图 3 马里亚纳海沟不同深度分离的异养细菌多样性 Figure 3 Diversity of heterotrophic bacteria isolated from different depths of sediments of the Mariana Trench. A: at phylum level; B: at class level; C: at genus level (top 26 dominant genera). |

2.3 不同培养基获得的异养细菌多样性

本研究采用2216E、R2A和TCBS 3种常规培养基及TCBS肉汤和AP 2种富集培养基对马里亚纳海沟沉积物样品中的异养细菌进行分离培养。从2216E中获得621株细菌(7纲),从R2A获得189株(5纲),从TCBS平板获得59株(4纲),从TCBS肉汤富集培养基获得65株(4纲),从AP培养基获得123株(5纲) (图 4)。在门水平,2216E、R2A及AP培养基均获得变形菌门、放线菌门、厚壁菌门和拟杆菌门4个门的微生物,而TCBS平板及TCBS肉汤培养基缺少拟杆菌门细菌。变形菌门在5种培养基上均具绝对优势,其在R2A上比例最高。厚壁菌门在2216E和R2A上比例较低,在另外3种培养基中比例较高。放线菌门在AP培养基中比例最高(图 4-A)。在纲水平,仅2216E分离培养出7个纲的菌株,R2A培养基缺少β-变形菌纲和噬纤维菌纲的菌株,TCBS平板和肉汤培养基缺少黄杆菌纲和噬纤维菌纲,在AP培养基中缺乏β-变形菌纲和黄杆菌纲。同变形菌门一样,γ-变形菌纲在5种培养基上都占绝对优势,在R2A上分得的比例最高(图 4-B)。

|

| 图 4 5种不同培养基分离培养的异养细菌多样性 Figure 4 Diversity of heterotrophic bacteria isolated and cultured in 5 different media. A: at phylum level; B: at class level. The number in brackets represents the number of isolates. |

此次研究共分离培养出101株潜在新分类单元(16S rRNA基因相似度低于98.65%) (图 5)。其中,2216E中分离出59株潜在新分类单元,分属于22个物种,疑似新种率为9.5%;R2A中分离出6株,分属于4个物种,疑似新种率为3.2%;TCBS平板分离出7株,分属于6个物种,疑似新种率为11.9%;TCBS肉汤培养出4株,分属于2个物种,疑似新种率为6.2%;AP培养基培养出25株,分属于12个物种,疑似新种率最高,达20.3%。

|

| 图 5 马里亚纳海沟沉积物潜在新分类单元与参考菌株的系统发育树 Figure 5 Neighbor-joining phylogenetic tree of potential novel taxa of bacteria from sediments of the Mariana Trench and their closest relatives based on 16S rRNA gene sequences. Top-hit taxon of potential novel taxa are in italics. The nucleotide substitution rate was 0.1. |

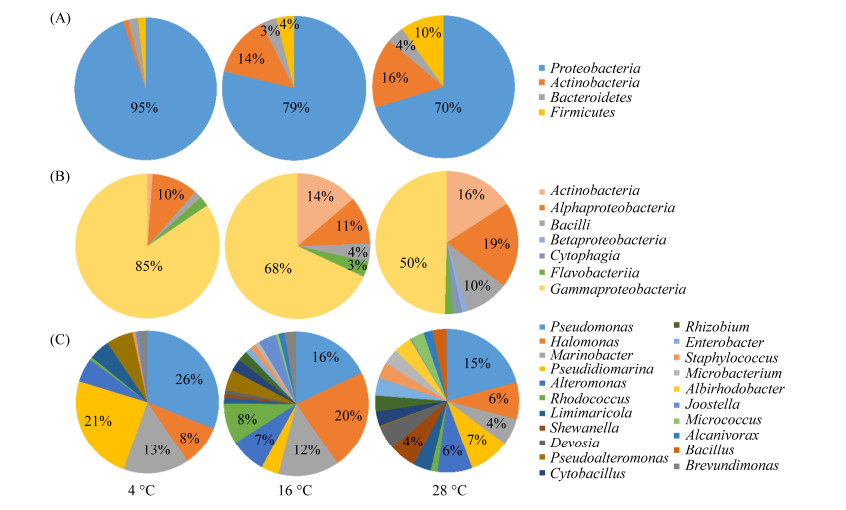

2.4 不同温度培养获得的异养细菌多样性

本研究采用4 ℃、16 ℃和28 ℃ 3个温度对马里亚纳海沟沉积物微生物进行分离培养。4 ℃获得菌株174株(5纲),16 ℃获得348株(5纲),28 ℃获得535株(7纲) (图 6)。4 ℃、16 ℃和28 ℃ 3个培养温度都能分离培养出变形菌门、放线菌门、拟杆菌门和厚壁菌门细菌。低温对变形菌门的选择性更好,4 ℃分离得到的变形菌门菌株数占总菌株的94.83%。随着培养温度的升高,变形菌门比例下降。相反,较高的温度对放线菌门、拟杆菌门和厚壁菌门的选择性更高(图 6-A)。在纲水平,仅在28 ℃分离得到噬纤维菌纲和β-变形菌纲。此外,28 ℃对放线菌,芽孢杆菌和α-变形菌纲的选择性更好,16 ℃对黄杆菌的选择性更好,而4 ℃对γ-变形菌纲的选择性更好(图 6-B)。在4 ℃共分离培养出22属,在16 ℃分离培养出39属,在28 ℃分离培养出65属(图 6-C)。其中Aureimonas、Arenibacter、Paenibacillus、Paenisporosarcina和Salinicola,仅在4 ℃分离得到;Acinetobacter、Croceicoccus、Chryseoglobus和Altererythrobacter仅在16 ℃分离到;Algoriphagus、Stappia、Achromobacter、Corynebacterium等29个属仅在28 ℃分离到。此外,4 ℃对假单胞菌属和假海源菌属的选择性更高,盐单胞菌属在16 ℃更有优势(图 6-C)。另外,在4 ℃分离培养出10株潜在新分类单元,潜在新种率为5.7%;16 ℃培养出32株潜在新分类单元,疑似新种率为9.2%;28 ℃培养出59株潜在新分类单元,疑似新种率为11.0%。可见,在本研究中随培养温度升高,疑似新种率也升高。

|

| 图 6 不同培养温度分离培养的异养细菌多样性 Figure 6 Diversity of heterotrophic bacteria isolated and cultivated at different culture temperature. A: at phylum level; B: at class level; C: at genus level (top 21 dominant genera). |

2.5 DMSP降解菌株

为探索马里亚纳海沟沉积物微生物参与DMSP代谢情况,按属的分类水平选取分离纯化得到的异养细菌134株,来自134个物种,进行DMSP降解能力检测。这些菌株涵盖4门(变形菌门75株、放线菌门35株、厚壁菌门19株、拟杆菌门5株)、6纲(γ-变形菌纲52株、α-变形菌纲22株、芽孢杆菌纲19株、放线菌纲35株、黄杆菌纲3株、噬纤维菌纲2株、β-变形菌纲1株)、71属。共获得DMSP降解菌52株,占总检测菌株的38.8%,分属于4门6纲31属,其中包含变形菌门33株(α-变形菌纲8株,γ-变形菌纲24株,β-变形菌纲1株),占被测变形菌门菌株(75株)的44%;厚壁菌门DMSP降解菌5株,占被测厚壁菌门菌株(19株)的26.3%;放线菌门13株,占被测放线菌菌株(35株)的37.1%。DMSP降解菌主要为变形菌门细菌,占DMSP降解菌株的63.5% (表 2)。在属水平,DMSP降解菌中假单胞菌属最多,为7株,海杆菌属次之,为6株,盐单胞菌属和微球菌属(Micrococcus)各3株,芽孢杆菌属、假海源菌属、德沃斯氏菌属(Devosia)、葡萄球菌属(Staphylococcus)、海源菌属(Idiomarina)、Limimaricola各2株。红球菌属、希瓦氏菌属、白色红杆菌属、短状杆菌属(Brachybacterium)、气微菌属(Aeromicrobium)、微杆菌属(Microbacterium)、类诺卡氏菌属(Nocardioides)、大洋芽孢杆菌属(Oceanobacillus)、根瘤菌属(Rhizobium)、Achromobacter、Acinetobacter、Agrococcus、Alishewanella、Cereibacter、Janibacter、Kocuria、Mycetocola、Mycolicibacterium、Salegentibacter、Stappia和Stenotrophomonas各1株(表 2)。此外,在这52株DMSP降解菌中有6株为疑似新分类单元。

| Strain number | Closest relatives | Class | DMSP-dependent DMS production activity/ [nmol DMS/(mg protein·h)] | DMSP-dependent MeSH production activity |

| RH815 | Aeromicrobium endophyticum | Actinobacteria | 0.1487 | - |

| RH830 | Agrococcus lahaulensis | Actinobacteria | 0.9266 | + |

| LRH860 | Brachybacterium paraconglomeratum | Actinobacteria | 0.0384 | + |

| LRH457 | Janibacter melonis | Actinobacteria | 1.0512 | + |

| LRH592 | Kocuria rosea | Actinobacteria | 0.8552 | + |

| LYU058 | Microbacterium luteolum | Actinobacteria | 1.1312 | + |

| LRH197-2 | Micrococcus flavus | Actinobacteria | 0.5987 | - |

| LRH888 | Micrococcus luteus | Actinobacteria | 0.5589 | + |

| LRH801 | Micrococcus endophyticus | Actinobacteria | 4.7405 | - |

| LRH564 | Mycetocola manganoxydans | Actinobacteria | 1.6238 | + |

| LRH790 | Mycolicibacterium iranicum | Actinobacteria | 0.7358 | + |

| LRH862* | Nocardioides pyridinolyticus | Actinobacteria | 3.3971 | + |

| LRH369 | Rhodococcus qingshengii | Actinobacteria | 0.8744 | + |

| LYU017 | Albirhodobacter confluentis | Alphaproteobacteria | 0.3037 | + |

| LYU010 | Cereibacter changlensis | Alphaproteobacteria | 0.2608 | + |

| LRH807 | Devosia limi | Alphaproteobacteria | 0.3254 | + |

| LYU011 | Devosia indica | Alphaproteobacteria | 0.1023 | + |

| LYU234 | Limimaricola soesokkakensis | Alphaproteobacteria | 0.6118 | - |

| LYU901 | Limimaricola variabilis | Alphaproteobacteria | 2.9658 | + |

| LYU026 | Rhizobium marinum | Alphaproteobacteria | 0.1427 | - |

| LRH824 | Stappia indica | Alphaproteobacteria | 0.1786 | + |

| LRH843* | Bacillus subtilis | Bacilli | 0.2062 | + |

| LRH684* | Bacillus kokeshiiformis | Bacilli | 0.2765 | + |

| LRH917 | Oceanobacillus kimchii | Bacilli | 70.0627 | + |

| LRH595 | Staphylococcus cohnii | Bacilli | 0.5124 | + |

| LRH588 | Staphylococcus sciuri | Bacilli | 0.8993 | + |

| LYU025 | Achromobacter deleyi | Betaproteobacteria | 0.2957 | - |

| LRH264-2* | Salegentibacter mishustinae | Flavobacteriia | 0.5316 | + |

| LRH348 | Acinetobacter lwoffii | Gammaproteobacteria | 0.4377 | + |

| LYU095 | Alishewanella jeotgali | Gammaproteobacteria | 0.1924 | + |

| LYU516 | Halomonas axialensis | Gammaproteobacteria | 0.0940 | + |

| LRH186-1 | Halomonas piezotolerans | Gammaproteobacteria | 0.0453 | + |

| LRH379 | Halomonas titanicae | Gammaproteobacteria | 1.3626 | + |

| LYU159 | Idiomarina piscisalsi | Gammaproteobacteria | 0.6330 | + |

| LRH371 | Idiomarina loihiensis | Gammaproteobacteria | 1.0756 | + |

| LRH191 | Marinobacter shengliensis | Gammaproteobacteria | 0.2165 | + |

| LRH190 | Marinobacter hydrocarbonoclasticus | Gammaproteobacteria | 0.1634 | + |

| LYU149 | Marinobacter vinifirmus | Gammaproteobacteria | 1.0701 | + |

| LRH353* | Marinobacter bryozoorum | Gammaproteobacteria | 1.1223 | + |

| LRH224 | Marinobacter gudaonensis | Gammaproteobacteria | 1.1470 | + |

| LYU105 | Marinobacter adhaerens | Gammaproteobacteria | 12.2126 | + |

| LYU392 | Idiomarina andamanensis | Gammaproteobacteria | 0.9607 | + |

| LRH460 | Pseudidiomarina donghaiensis | Gammaproteobacteria | 0.6073 | + |

| LRH582 | Pseudomonas lactis | Gammaproteobacteria | 0.1545 | + |

| LRH236-3* | Pseudomonas oleovorans | Gammaproteobacteria | 0.7429 | + |

| LYU337 | Pseudomonas songnenensis | Gammaproteobacteria | 0.3957 | + |

| LYU034 | Pseudomonas alloputida | Gammaproteobacteria | 0.3265 | + |

| LRH758 | Pseudomonas alcaliphila | Gammaproteobacteria | 0.2682 | + |

| LRH456 | Pseudomonas zhaodongensis | Gammaproteobacteria | 1.4540 | + |

| LRH330 | Pseudomonas juntendi | Gammaproteobacteria | 1.5264 | + |

| LRH708 | Shewanella algae | Gammaproteobacteria | 11.1510 | + |

| LRH819 | Stenotrophomonas pavanii | Gammaproteobacteria | 0.1737 | + |

| LZB033 | Labrenzia aggregata | Alphaproteobacteria | 9.2934 | - |

| DMSP lysed strains that can produce MeSH are indicated by “+”, and MeSH cannot be produced by “-”. Strains numbers with * represent potential novel taxa of bacteria. | ||||

同时在筛选DMSP降解菌过程中,发现部分菌株也可通过脱甲基途径降解DMSP产生MeSH。可通过裂解途径降解DMSP的菌株共计52株,其中有46株也可以通过脱甲基途径降解DMSP生成MeSH (表 2)。

3 讨论深海沉积物拥有丰富的微生物群落,这些微生物在生物地球化学循环中具有重要作用[30]。尽管目前免培养方法(如16S rRNA基因高通量测序和宏基因组学)已广泛应用于深海环境微生物的多样性和潜在代谢通路研究,但要深入了解这些微生物的生命特征和功能仍然需要对其进行纯培养研究。本研究对马里亚纳海沟沉积物微生物进行了规模化分离培养和鉴定,所获得的异养细菌在一定程度上反映了马里亚纳海沟的微生物群落组成。

本研究共采用5个站位马里亚纳海沟沉积物样品,在5种培养基和3个培养温度完成了1057株细菌的分离纯化及16S rRNA基因测序分析。马里亚纳海沟沉积物可培养异养细菌由变形菌门、厚壁菌门、放线菌门和拟杆菌门组成,γ-变形菌纲、α-变形菌纲、放线菌纲和芽孢杆菌纲为优势菌群,这与先前从马里亚纳海沟水体中分离到异养细菌的优势菌群一致[31],此次沉积物样品并未分离培养出ε-变形菌纲(Epsilonproteobacteria)、腈基降解菌纲(Nitriliruptoria)和酸微菌纲(Acidimicrobiia),但分离到了水体样品中未获得的β-变形菌纲。先前从南太平洋环流区沉积物中分离获得放线菌门、变形菌门、厚壁菌门和拟杆菌门,与本研究结果一致,但其优势门类为放线菌门[32],与本研究优势门类为变形菌门的结果不同。推测可能是由于不同海域的沉积物成分及深度不同导致了微生物的群落组成差异。本研究分离得到的可培养细菌分属于76属、170种,所获得的可培养细菌种类多于从南太平洋环流区沉积物中获得的可培养细菌(50属、95物种)[32]。本研究除使用2216E与R2A固体培养基以外,还采用TCBS系列培养基和AP培养基,多种培养基结合培养可以分离得到种类更为丰富的异养微生物。本研究在AP培养基的疑似新种率高达20.3%,远高于R2A培养基3.2%的疑似新种率,这与先前海沟水体可培养异养细菌在R2A培养基的疑似新种率较高的结果存在差异[31]。众所周知,海洋水体具有寡营养的特点,但海洋沉积物中营养物质的浓度远高于水体,因此推测AP这种富营养培养基可能更适合于从沉积物中获得更多的可培养异养细菌。TCBS系列培养基为弧菌选择性培养基,但遗憾的是,本次试验中并未筛选出弧菌,推测与航行期间细菌被培养时间过长,而导致TCBS培养基中硫代硫酸钠和柠檬酸钠活性降低有关,最终导致了非弧菌的其他细菌的生长。另外,放线菌是一类高G+C含量的革兰氏阳性菌,能产生丰富的活性次生代谢产物,推测其需要更多的营养物质来供给自身代谢需要,因此其在营养物质更丰富的富集培养基(AP及TCBS肉汤培养基)的相对丰度更高。

在海沟沉积物的不同取样深度,可培养异养细菌的多样性也存在差异。变形菌门在多种培养条件下均是最优势的可培养类群,显示出其广泛的环境适应性。在海沟沉积物的表层和深层,变形菌门细菌的多样性存在差异。其中假单胞菌、盐单胞菌和海杆菌属细菌在表层的相对丰度高于深层,推测可能是因为这3个属的细菌为好氧菌,而表层沉积物的含氧量高于深层,导致好氧菌更容易存活。厚壁菌门在深层所占比例更高,这可能是因为其中的芽孢杆菌大多可形成抗逆性极强的芽孢来抵抗不良环境,导致其在含氧量和营养物质浓度更低的深层沉积物中相对丰度较高。

温度是调节微生物代谢和生长活力的重要因素,直接影响微生物细胞中的代谢反应,是决定微生物多样性的重要因素之一。本研究采用4 ℃、16 ℃和28 ℃ 3个温度来培养微生物,在28 ℃培养出来的微生物多样性最高。有5个属的细菌仅在4 ℃获得,有4个属仅在16 ℃获得,低温环境与海沟的原位温度更为接近,能够作为常规培养条件的补充。这也说明了多种培养温度有利于分离得到种类更丰富的微生物。

探究参与DMSP降解的微生物物种,有助于了解海洋微生物在硫循环以及气候变化中的作用。目前广泛认知中,参与DMSP裂解的细菌主要来源于变形菌门的γ-变形菌纲和α-变形菌纲,其中α-变形菌纲中的玫瑰杆菌类群(Rosebacter clade)和SAR11类群(SAR11 clade)是裂解DMSP的最主要类群[20, 33]。其他类群除红球菌以及厚壁菌门梭菌属(Clostridium)外,关于细菌DMSP降解活性的报道较少。本研究共获得52株DMSP裂解菌,占总测试菌的38.8%,分属于4门31属,物种较为丰富,高于Curson等[34]通过宏基因组预测到的裂解DMSP微生物的比例(~20%)。值得注意的是,本研究得出的海沟沉积物中38.8%的可培养菌具有DMSP裂解能力这一比例不能用于反应环境中真实具有DMSP裂解活性细菌的比例,因为可培养细菌仅占环境中总微生物的很少一部分。本研究中的DMSP降解菌株,主要为变形菌门的α-变形菌纲与γ-变形菌纲,与已报道的DMSP主要降解类群相符,但本研究并未分离培养出α-变形菌纲中的玫瑰杆菌(Rosebacter clade)和SAR11 (SAR11 clade)这两大裂解DMSP的主要类群,这可能是由于纯培养条件的限制使得这两大类群的菌株没有被培养出来,而且这两类细菌在沉积物中所占的比例远低于海水。其余降解菌株为13株放线菌门与5株厚壁菌门以及1株拟杆菌门细菌。目前有报道称放线菌门中的放线菌纲具有DMSP裂解能力[20],本研究中气微菌属、短状杆菌属、微杆菌属、微球菌属、Janibacter、Kocuria和Agrococcus这些来自于放线菌纲的细菌有DMSP降解能力。从动物肠道分离出的一株假单胞菌,添加DMSP为唯一碳源也能够裂解产生DMS[35]。盐单胞菌属细菌不仅具有DMSP合成能力也被证实有DMSP裂解能力[36]。另外,本研究发现了多种新型DMSP降解菌属,目前有报道称厚壁菌门中梭菌属菌株具有裂解DMSP能力[37],但尚未见芽孢杆菌属细菌降解DMSP的报道。变形菌门的海源菌属尚未见关于DMSP代谢以及硫循环相关报道,海杆菌属只被报道过具有DMSP合成活性[38],尚未见与DMSP降解相关报道。本研究为发掘DMSP降解新通路提供了新型菌株,有助于了解超深渊微生物在DMSP循环乃至硫元素的生物地球化学循环中的作用,具有显著的科学价值。

| [1] |

Li HR, Yu Y, Zeng YX, Chen B, Ren DM. Phylogenetic analysis of bacterial diversity in Pacific Arctic sediments. Acta Microbiologica Sinica, 2006, 46(2): 177-183.

(in Chinese) 李会荣, 俞勇, 曾胤新, 陈波, 任大明. 北极太平洋扇区海洋沉积物细菌多样性的系统发育分析. 微生物学报, 2006, 46(2): 177-183. DOI:10.3321/j.issn:0001-6209.2006.02.003 |

| [2] | Zhang F, Lin J, Zhan WH. Variations in oceanic plate bending along the Mariana trench. Earth and Planetary Science Letters, 2014, 401: 206-214. DOI:10.1016/j.epsl.2014.05.032 |

| [3] | Zhou ZY, Lin J, Behn MD, Olive JA. Mechanism for normal faulting in the subducting plate at the Mariana Trench. Geophysical Research Letters, 2015, 42(11): 4309-4317. DOI:10.1002/2015GL063917 |

| [4] | Morita RY. Survival of bacteria in cold and moderate hydrostatic pressure environments with special reference to psychrophilic and barophilic bacteria//The Survival of Vegetative Microbes. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1976: 279-298. |

| [5] | Takami H, Inoue A, Fuji F, Horikoshi K. Microbial flora in the deepest sea mud of the Mariana Trench. FEMS Microbiology Letters, 1997, 152(2): 279-285. DOI:10.1111/j.1574-6968.1997.tb10440.x |

| [6] | Peoples LM, Donaldson S, Osuntokun O, Xia Q, Nelson A, Blanton J, Allen EE, Church MJ, Bartlett DH. Vertically distinct microbial communities in the Mariana and Kermadec trenches. PLoS One, 2018, 13(4): e0195102. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0195102 |

| [7] | Nunoura T, Takaki Y, Hirai M, Shimamura S, Makabe A, Koide O, Kikuchi T, Miyazaki J, Koba K, Yoshida N, Sunamura M, Takai K. Hadal biosphere: insight into the microbial ecosystem in the deepest ocean on Earth. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 2015, 112(11): E1230-E1236. DOI:10.1073/pnas.1421816112 |

| [8] | Tarn J, Peoples LM, Hardy K, Cameron J, Bartlett DH. Identification of free-living and particle-associated microbial communities present in hadal regions of the Mariana Trench. Frontiers in Microbiology, 2016, 7: 665. |

| [9] | Tian JW, Fan L, Liu HD, Liu JW, Li Y, Qin QL, Gong Z, Chen HT, Sun ZB, Zou L, Wang XC, Xu HZ, Bartlett D, Wang M, Zhang YZ, Zhang XH, Zhang CL. A nearly uniform distributional pattern of heterotrophic bacteria in the Mariana Trench interior. Deep Sea Research Part I: Oceanographic Research Papers, 2018, 142: 116-126. DOI:10.1016/j.dsr.2018.10.002 |

| [10] | Liu JW, Zheng YF, Lin HY, Wang XC, Li M, Liu Y, Yu M, Zhao MX, Pedentchouk N, Lea-Smith DJ, Todd JD, Magill CR, Zhang WJ, Zhou S, Song DL, Zhong HH, Xin Y, Yu M, Tian JW, Zhang XH. Proliferation of hydrocarbon-degrading microbes at the bottom of the Mariana Trench. Microbiome, 2019, 7(1): 47. DOI:10.1186/s40168-019-0652-3 |

| [11] | Rappé MS, Giovannoni SJ. The uncultured microbial majority. Annual Review of Microbiology, 2003, 57(1): 369-394. DOI:10.1146/annurev.micro.57.030502.090759 |

| [12] | Amend JP, LaRowe DE. Ocean Sediments-an enormous but underappreciated microbial habitat. Microbe, 2016, 11(12): 427-432. |

| [13] | Kato C, Li L, Nogi Y, Nakamura Y, Tamaoka J, Horikoshi K. Extremely barophilic bacteria isolated from the Mariana Trench, Challenger Deep, at a depth of 11, 000 meters. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 1998, 64(4): 1510-1513. DOI:10.1128/AEM.64.4.1510-1513.1998 |

| [14] | Kettle AJ, Andreae MO. Flux of dimethylsulfide from the oceans: A comparison of updated data sets and flux models. Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres, 2000, 105(D22): 26793-26808. DOI:10.1029/2000JD900252 |

| [15] | Ksionzek KB, Lechtenfeld OJ, McCallister SL, Schmitt-Kopplin P, Geuer JK, Geibert W, Koch BP. Dissolved organic sulfur in the ocean: Biogeochemistry of a petagram inventory. Science, 2016, 354(6311): 456-459. DOI:10.1126/science.aaf7796 |

| [16] | Lovelock JE, Maggs RJ, Rasmussen RA. Atmospheric dimethyl sulphide and the natural sulphur cycle. Nature, 1972, 237(5356): 452-453. DOI:10.1038/237452a0 |

| [17] | Charlson RJ, Lovelock JE, Andreae MO, Warren SG. Oceanic phytoplankton, atmospheric sulphur, cloud albedo and climate. Nature, 1987, 326(6114): 655-661. DOI:10.1038/326655a0 |

| [18] | Ayers GP, Gras JL. Seasonal relationship between cloud condensation nuclei and aerosol methanesulphonate in marine air. Nature, 1991, 353(6347): 834-835. DOI:10.1038/353834a0 |

| [19] | Andreae MO, Crutzen PJ. Atmospheric aerosols: Biogeochemical sources and role in atmospheric chemistry. Science, 1997, 276(5315): 1052-1058. DOI:10.1126/science.276.5315.1052 |

| [20] | Curson ARJ, Todd JD, Sullivan MJ, Johnston AWB. Catabolism of dimethylsulphoniopropionate: microorganisms, enzymes and genes. Nature Reviews Microbiology, 2011, 9(12): 849-859. DOI:10.1038/nrmicro2653 |

| [21] | Moran MA, Reisch CR, Kiene RP, Whitman WB. Genomic insights into bacterial DMSP transformations. Annual Review of Marine Science, 2012, 4: 523-542. DOI:10.1146/annurev-marine-120710-100827 |

| [22] | Reisch CR, Moran MA, Whitman WB. Bacterial catabolism of dimethylsulfoniopropionate (DMSP). Frontiers in Microbiology, 2011, 2: 172. |

| [23] | Kiene RP, Linn LJ. The fate of dissolved dimethylsulfoniopropionate (DMSP) in seawater: tracer studies using 35S-DMSP. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta, 2000, 64(16): 2797-2810. DOI:10.1016/S0016-7037(00)00399-9 |

| [24] | 张晓华, 等. 海洋微生物学. 第2版. 北京: 科学出版社, 2016: 1-464. |

| [25] | Zheng YF, Wang JY, Zhou S, Zhang YH, Liu J, Xue CX, Williams BT, Zhao XX, Zhao L, Zhu XY, Sun C, Zhang HH, Xiao T, Yang GP, Todd JD, Zhang XH. Bacteria are important dimethylsulfoniopropionate producers in marine aphotic and high-pressure environments. Nature Communications, 2020, 11(1): 4658. DOI:10.1038/s41467-020-18434-4 |

| [26] | Moore E, Arnscheidt A, Krüger A, Strömpl C, Mau M. Simplified protocols for the preparation of genomic DNA from bacterial cultures//Molecular Microbial Ecology Manual. Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic Publishers, 1999: 1-15. |

| [27] | Weisburg WG, Barns SM, Pelletier DA, Lane DJ. 16S ribosomal DNA amplification for phylogenetic study. Journal of Bacteriology, 1991, 173(2): 697-703. DOI:10.1128/JB.173.2.697-703.1991 |

| [28] |

Du R, Yu M, Cheng JG, Zhang JJ, Tian XR, Zhang XH. Diversity and sulfur oxidation characteristics of cultivable sulfur oxidizing bacteria in hydrothermal fields of Okinawa Trough. Acta Microbiologica Sinica, 2019, 59(6): 1036-1049.

(in Chinese) 杜瑞, 于敏, 程景广, 张静静, 田晓荣, 张晓华. 冲绳海槽热液区可培养硫氧化细菌多样性及其硫氧化特性. 微生物学报, 2019, 59(6): 1036-1049. |

| [29] | Curson ARJ, Liu J, Martínez AB, Green RT, Chan YH, Carrión O, Williams BT, Zhang SH, Yang GP, Page PCB, Zhang XH, Todd JD. Dimethylsulfoniopropionate biosynthesis in marine bacteria and identification of the key gene in this process. Nature Microbiology, 2017, 2(5): 17009. DOI:10.1038/nmicrobiol.2017.9 |

| [30] | Bienhold C, Zinger L, Boetius A, Ramette A. Diversity and biogeography of bathyal and abyssal seafloor bacteria. PLoS One, 2016, 11(1): e0148016. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0148016 |

| [31] | Zhao XX, Liu JW, Zhou S, Zheng YF, Wu YH, Kogure K, Zhang XH. Diversity of culturable heterotrophic bacteria from the Mariana Trench and their ability to degrade macromolecules. Marine Life Science & Technology, 2020, 2(2): 181-193. DOI:10.1007/s42995-020-00027-1?utm_medium=cpc |

| [32] | 李昭. 南太平洋环流区深海可培养细菌的多样性研究以及两株海洋新菌的分类鉴定. 中国海洋大学博士学位论文, 2013. |

| [33] | Curson ARJ, Rogers R, Todd JD, Brearley CA, Johnston AWB. Molecular genetic analysis of a dimethylsulfoniopropionate lyase that liberates the climate-changing gas dimethylsulfide in several marine α-proteobacteria and Rhodobacter sphaeroides. Environmental Microbiology, 2008, 10(3): 757-767. DOI:10.1111/j.1462-2920.2007.01499.x |

| [34] | Curson ARJ, Williams BT, Pinchbeck BJ, Sims LP, Martínez AB, Rivera PPL, Kumaresan D, Mercadé E, Spurgin LG, Carrión O, Moxon S, Cattolico RA, Kuzhiumparambil U, Guagliardo P, Clode PL, Raina JB, Todd JD. DSYB catalyses the key step of dimethylsulfoniopropionate biosynthesis in many phytoplankton. Nature Microbiology, 2018, 3(4): 430-439. DOI:10.1038/s41564-018-0119-5 |

| [35] | Curson ARJ, Sullivan MJ, Todd JD, Johnston AWB. Identification of genes for dimethyl sulfide production in bacteria in the gut of Atlantic Herring (Clupea harengus). The ISME Journal, 2010, 4(1): 144-146. DOI:10.1038/ismej.2009.93 |

| [36] | Todd JD, Curson ARJ, Nikolaidou-Katsaraidou N, Brearley CA, Watmough NJ, Chan Y, Page PCB, Sun L, Johnston AWB. Molecular dissection of bacterial acrylate catabolism-unexpected links with dimethylsulfoniopropionate catabolism and dimethyl sulfide production. Environmental Microbiology, 2010, 12(2): 327-343. DOI:10.1111/j.1462-2920.2009.02071.x |

| [37] | Wagner C, Stadtman ER. Bacterial fermentation of dimethyl-β-propiothetin. Archives of Biochemistry and Biophysics, 1962, 98(2): 331-336. DOI:10.1016/0003-9861(62)90191-1 |

| [38] | Williams BT, Cowles K, Martínez AB, Curson ARJ, Zheng YF, Liu JL, Newton-Payne S, Hind AJ, Li CY, Rivera PPL, Carrión O, Liu J, Spurgin LG, Brearley CA, Mackenzie BW, Pinchbeck BJ, Peng M, Pratscher J, Zhang XH, Zhang YZ, Murrell JC, Todd JD. Bacteria are important dimethylsulfoniopropionate producers in coastal sediments. Nature Microbiology, 2019, 4(11): 1815-1825. DOI:10.1038/s41564-019-0527-1 |

2021, Vol. 61

2021, Vol. 61