中国科学院微生物研究所,中国微生物学会,中国菌物学会

文章信息

- 董志祥, 李宏伟, 郭军, 林连兵, 张棋麟. 2020

- Dong Zhixiang, Li Hongwei, Guo Jun, Lin Lianbing, Zhang Qilin. 2020

- 西方蜜蜂工蜂肠道菌群定殖起始点和定殖稳态点的结构比较分析

- Comparison of intestinal flora structure between starting point and steady point of colonization in workers (Apis mellifera)

- 微生物学报, 60(7): 1447-1457

- Acta Microbiologica Sinica, 60(7): 1447-1457

-

文章历史

- 收稿日期:2019-10-09

- 修回日期:2019-12-11

- 网络出版日期:2020-05-18

2. 云南省高校饲用抗生素替代技术工程研究中心, 云南 昆明 650500

2. Engineering Research Center for Replacement Technology of Feed Antibiotics of Yunnan College, Kunming 650500, Yunnan Province, China

蜜蜂是重要的经济昆虫,在农业授粉和生态系统中都发挥了重要的作用。西方蜜蜂(Apis mellifara)因适应能力强、产蜜量高、抗逆特性强等优点,是我国饲养最为广泛的蜜蜂物种[1]。蜂群主要以“三型蜂”存在,即1只蜂王、成千上万只工蜂和数百只雄性蜂组成[2]。其中,工蜂个体较小,但蜂群内所有外勤和内勤活动(包括采集水和花蜜,哺育饲喂幼蜂,防御天敌,清理蜂房等)几乎都由工蜂承担。然而,近些年蜜蜂的生存受到了巨大的威胁,特别是美国报道了蜂群衰竭失调症(colony collapse disorder,CCD):蜂房内的工蜂神秘失踪,工蜂的健康受到了更加广泛的关注[3]。蜂群衰竭可能是多种原因导致的,包括病原体和寄生虫引起的疾病、农药的急性和亚致死毒性以及因丧失觅食栖息地而造成的营养不良,这些不利因素导致全球蜜蜂健康和种群数量显著下降[4–5]。为解决这一难题,更多研究者开始关注肠道菌群对蜜蜂健康的影响。

肠道菌群被称为第二基因组[6]。肠道菌群与宿主之间的关系密切,在宿主的发育[7]、代谢[8]、免疫[9]、疾病[10]中都发挥了重要的功能。先前的研究表明,工蜂肠道内主要栖息着9种细菌,其中有5种广泛存在于蜜蜂肠道内,被称为蜜蜂的核心肠道菌群,包括两种乳酸菌Lactobacillus Firm-4和Lactobacillus Firm-5、Snodgrassella alvi、Gilliamella apicola和Bifidobacterium[11–13]。其余4种在肠道内数量不多且分布不稳定,他们分别是Frischella perrara、Bartonella apis、Parasaccharibacter apium、Alpha 2.1[14–15]。这些菌群在蜜蜂的健康与疾病中都扮演了重要的角色。然而,通过传统细菌纯培养技术无法获得宿主肠道内所有的细菌信息,且肠道内栖息的大量微生物属于厌氧型细菌,无法通过纯培养获得。高通量测序技术的发展极大地促进了肠道菌群的研究[16],特别是促进了蜜蜂肠道菌群相关的研究,经过十年的发展,对蜜蜂肠道菌群的组成结构及功能都有了更清晰的认识。例如,Jones等对暴露在不同环境下的工蜂肠道菌群(16S rDNA)进行高通量测序,发现蜜蜂所处的环境对该微生物群落中某些成员的相对丰度有一定的影响[17]。当蜜蜂暴露于草甘膦农药时,肠道内的益生菌受到破坏,增加了蜜蜂的死亡率[18]。此外,当蜜蜂感染孢子虫后,也会破坏宿主肠道菌群(16S rDNA)的结构,导致蜜蜂死亡[19]。这些研究都表明肠道菌群对宿主的免疫、健康都发挥着重要的作用。而肠道菌群功能的发挥依赖于肠道菌群的组成和结构。肠道菌群定殖是宿主菌群组成结构形成的基础[20]。有研究报道银鲫(Carassius auratus)肠道菌群会随着宿主的发育多样性显著增加[21]。Stephens等(2016)对不同发育状态的斑马鱼(Danio rerio)肠道菌群定殖规律进行了探索,其结果表明,斑马鱼肠道菌群个体差异随着宿主的发育逐渐增加[22]。然而,大多菌群定殖相关的研究都聚焦于哺乳动物和鱼类等[23–24],对昆虫肠道菌群的定殖的研究并不多见。Powell等(2014)的研究表明工蜂的肠道菌群主要是通过社会接触获得[25],即未与社会接触的第0日龄是成年工蜂肠道菌群定殖(即肠道菌群种类基本固定)的起始点。此外,工蜂肠道内的菌群,尤其核心菌群,在第7日龄定殖完成,与成年工蜂的细菌类型几乎一致[26],即第7日龄是西方蜜蜂工蜂肠道菌群定殖的稳态点。

先前的大多数研究都聚焦于外界环境对西方蜜蜂肠道菌群的影响,宿主与肠道菌群之间的内在联系等,而忽视了工蜂生命阶段中两个关键节点之间优势肠道菌群差异,也没有研究表明这一重要过程中核心菌群与非核心菌群相对丰度的改变。因此,本研究通过高通量测序技术,对刚出房的工蜂(0日龄)和菌群定殖稳态的工蜂(7日龄)的肠道菌群进行深度测序。本次研究的结果不仅可增加我们对工蜂肠道菌群的认知,也能够为研究其他动物肠道菌群的定殖提供重要的参考信息。

1 材料和方法 1.1 工蜂样品本研究的样品采集时间为2019年3月。为确定工蜂的年龄,我们选择了一群健康的西方蜜蜂,并从中挑选了一框含有快出房幼蜂的巢批,将巢批上的个体抖落后,使用镊子取出5只正出房的幼蜂(幼蜂未与其他工蜂接触),放入1.5 mL的离心管,标记为0日龄,并立即放入–80 ℃冰箱。接下来,将巢批放入黑暗的孵育箱之中,温度调节为34 ℃ (模拟蜂房环境),收集刚出房的幼蜂,并使用红色珐琅漆在蜜蜂的背部进行标记,将标记好的20只幼蜂放入原群,使之自然生长。记录时间,在第7天时打开蜂箱,分别取出5只有标记的工蜂,放入1.5 mL的离心管,标记为7日龄,并立即放入–80 ℃冰箱。等待DNA的提取。

1.2 DNA抽提和PCR扩增将样品放置超净工作台,进行解剖。分别将每个肠道样品取出,并转移至1.5 mL的离心管。根据TIANamp Stool DNA Kit (天根生物技术公司,中国)试剂盒说明书进行总DNA抽提。利用NanoDrop 1000 (Thermo Scientific,美国)对DNA浓度和纯度进行检测,进一步利用1.5%琼脂糖凝胶电泳检测DNA完整度。用338F (5′-ACTCCTAC GGGAGGCAGCAG-3′)和806R (5′-GGACTACHV GGGTWTCTAAT-3′)引物对V3-V4可变区进行PCR扩增,扩增程序为:95 ℃ 3 min;95 ℃ 30 s,55 ℃ 30 s,72 ℃ 30 s,27个循环;72 ℃ 10 min。扩增体系为20 μL:4 μL 5倍FastPfu缓冲液,2 μL 2.5 mmol/L dNTPs,0.8 μL引物(5 μmol/L),0.4 μL FastPfu聚合酶;10 ng模板DNA。

1.3 Illumina测序使用2%琼脂糖凝胶回收PCR产物,利用AxyPrep DNA Gel Extraction Kit (AxygenBiosciences,美国)进行纯化,Tris-HCl洗脱,1.5%琼脂糖电泳检测。利用QuantiFluor™-ST (Promega,美国)进行精确定量。根据Illumina标准操作规程将纯化后的扩增片段构建PE 300的文库。构建文库步骤:(1)连接“Y”字形接头;(2)使用磁珠筛选去除接头自连片段;(3)利用PCR扩增进行文库模板的富集;(4)氢氧化钠变性,产生单链DNA片段。所有高通量测序委托上海美吉生物医药科技有限公司在Illumina Miseq平台(Illumina,美国)上进行。

1.4 数据处理原始测序序列使用Trimmomatic软件(http://www.usadellab.org/cms/index.php?page=trimmomatic)质控,使用FLASH软件进行拼接:(1)设置50 bp的窗口,如果窗口内的平均质量值低于20 bp,从窗口前端位置截去该碱基后端所有序列,之后再去除质控后长度低于50 bp的序列。(2)根据片段重叠部分将两端序列进行拼接,拼接时重叠片段间的碱基最大错配率为0.2,长度大于10 bp。(3)根据序列首尾两端的barcode和引物将序列拆分至每个样本,barcode需精确匹配,引物允许2个碱基的错配,去除存在模糊碱基的序列。使用UPARSE软件(version 7.1,http://drive5.com/uparse/),根据97%的相似度对序列进行OTU聚类,并在聚类的过程中去除单序列和嵌合体。利用RDP classifier (http://rdp.cme.msu.edu/)对每条序列进行物种分类注释,比对至SILVA数据库(v128,https://www.arb-silva.de/)中的SSUrRNA子库,设置比对阈值为70%。

1.5 高通量测序结果验证通过实时荧光定量PCR (quantitative real-time PCR,qPCR)的方法对高通量测序数据进行验证。挑选2个种和2个属的细菌,实验所需细菌种/属特异引物和反应条件使用以前文献所报道的序列和程序[27–29]。将扩增到的PCR产物片段分别与T载体连接,转化至大肠杆菌DH5α感受态细胞中,选择阳性克隆后抽提其质粒,作为标准质粒,对标准质粒进行10倍梯度稀释6个梯度,并绘制标准曲线。然后以1.2节所提取的DNA为模板进行qPCR实验,qPCR扩增体系为9 μL SYBR Green Supermix,正向引物和反向引物各0.5 μL,2 μL DNA模板,13 μL无菌水。qPCR反应体系为:95 ℃ 8 min;95 ℃ 15 s,60 ℃ 1 min,40个循环,反应结束后进行溶解曲线分析。每个反应平行重复3次,使用IBM SPSS Statistics 22对结果进行统计分析。

1.6 统计方法实验中所有组间两两比较均使用T检验(Student’s t)。使用Venn图统计两组中所共有和独有的OTU数目。基于Bray-Curtis距离进行主成分分析(principal component analysis,PCA)。

2 结果和分析 2.1 测序结果对两个取样点的10个西方蜜蜂工蜂肠道微生物样品进行测序,一共得到515156条序列,长度为227904953 bp,平均长度为442.40 bp。基于97%的相似水平,工蜂肠道细菌通过聚类分析获得2469个OTU (表 1)。

| Gene | Number of valid tags | Number of OTUs | Number of different taxonomic categories | ||||

| Phylum | Class | Order | Family | Genera | |||

| 16S rDNA | 515156 | 2469 | 34 | 82 | 221 | 405 | 799 |

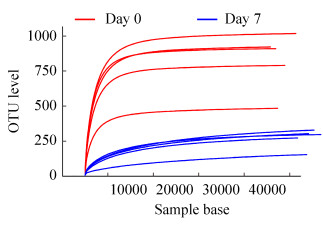

稀释曲线(rarefaction curve)反映各样本在不同测序数量时的微生物多样性,选择97%相似度的OTU分类学水平,利用mothur计算不同随机抽样下的Sobs指数,并使用R软件绘制稀释曲线(图 1)。从图 1可以看出,曲线趋向平坦,说明测序数据量充足。

|

| 图 1 不同样本的稀释曲线分析 Figure 1 Rarefaction analysis of the different samples. |

2.2 工蜂肠道菌群的组成及其相对丰度

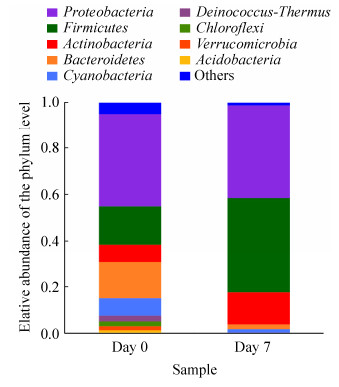

基于OTUs的分类表明,西方蜜蜂工蜂肠道细菌分属为34个门、82个纲、221个目、405个科、799个属(表 1)。西方蜜蜂工蜂肠道肠道菌群在门分类水平的组成如图 2所示。其中主要门类为变形菌门(Proteobacteria)、厚壁菌门(Firmicutes)、放线菌门(Actinobacteria)、拟杆菌门(Bacteroidetes)、蓝藻菌门(Cyanobacteria)、异常球菌(Deinococcus-Thermus)、绿弯菌门(Chloroflexi)疣微菌门(Verrucomicrobia)、酸杆菌门(Acidobacteria)等。其中变形菌门在0日龄和7日龄的工蜂肠道内的相对丰度都为40%左右。从图 2中还可以看出0日龄的工蜂肠道内厚壁菌门(16.5%和41.1%)、放线菌门(8.0%和13.3%)的丰度小于7日龄工蜂肠道内的丰度。然而,0日龄工蜂肠道内拟杆菌门的丰度高于7日龄,相对丰度分别为15.5%和2.0%。此外,0日龄肠道内的蓝藻菌门、异常球菌、绿弯菌门、疣微菌门、酸杆菌门的相对丰度均高于7日龄的相对丰度。

|

| 图 2 门水平肠道菌群组成 Figure 2 Bacterial community composition at Phylum level in different groups. |

2.3 工蜂肠道菌群Alpha和Beta多样性分析

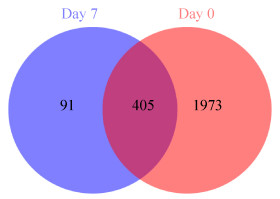

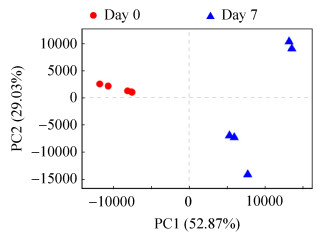

本研究通过Alpha多样性分析反映微生物群落的丰富度和多样性。使用Chao、ACE指数反映群落丰富度,使用Shannon、Simpson指数反映群落多样性。使用Coverage指数反映群落覆盖度(表 2)。通过比较分析发现0日龄工蜂肠道菌群和7日龄工蜂的肠道菌群多样性存在显著差异(ACE,P=0.0014;Chao,P=0.0013;Shannon,P=0.00033;Simpson,P=0.0028)。此外,Coverage指数均大于0.998,表明测序饱和,所获得数据能够充分代表西方蜜蜂肠道菌群。此外,0日龄工蜂肠道菌群的OTU数目显著高于7日龄(OTU,P=0.0012) (表 2)。对0日龄和7日龄肠道菌群的OTU进行交集分析发现,它们所共有的OTU数目为405个,第0天有1973个OTU数目是特有的,而第7天却只有91个特有的OTU数目(图 3)。根据PCA结果显示,0日龄和7日龄显著分开,表明本研究中实验样品处理可靠,且进一步说明刚出房幼蜂的肠道菌群的组成结构与7日龄工蜂肠道菌群的组成结构具有明显差异(图 4)。

| Sample names | Coverage | OTU | Diversity indices | |||

| Shannon | Simpson | ACE | Chao | |||

| 0_1 | 0.9995 | 921 | 5.44 | 0.03 | 926.15 | 932.55 |

| 0_2 | 0.9995 | 482 | 3.86 | 0.12 | 493.00 | 494.83 |

| 0_3 | 0.9995 | 909 | 5.55 | 0.02 | 914.60 | 924.83 |

| 0_4 | 0.9995 | 1017 | 5.53 | 0.02 | 1023.60 | 1032.79 |

| 0_5 | 0.9996 | 789 | 4.70 | 0.07 | 794.63 | 803.25 |

| 7_1 | 0.9987 | 326 | 2.18 | 0.23 | 371.65 | 361.75 |

| 7_2 | 0.9988 | 301 | 2.76 | 0.10 | 341.52 | 337.12 |

| 7_3 | 0.9994 | 295 | 2.34 | 0.21 | 310.80 | 310.53 |

| 7_4 | 0.9989 | 151 | 2.00 | 0.20 | 208.19 | 187.83 |

| 7_5 | 0.9989 | 270 | 2.48 | 0.12 | 302.19 | 299.17 |

| P value | / | 0.0012 | 0.00033 | 0.0028 | 0.0014 | 0.0013 |

|

| 图 3 OTU对比Venn图 Figure 3 OTU compares Venn diagrams. |

|

| 图 4 不同日龄工蜂样品PCA图 Figure 4 PCA plots for different groups. |

2.4 西方蜜蜂工蜂肠道菌群定殖起点和终点优势菌群相对丰度差异分析

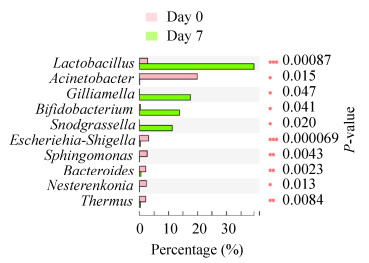

为探索西方蜜蜂工蜂肠道菌群定殖起点和终点间肠道菌群相对丰度的差异,选取西方蜜蜂工蜂肠道内优势菌群(肠道内的相对丰度高于1%的细菌)进行相对丰度差异分析。结果表明,乳酸杆菌Lactobacillus (P=0.0009)、不动杆菌Acinetobacter (P=0.015)、Gilliamella (P=0.0471)、双歧杆菌Bifidobacterium (P=0.0410)、Snodgrassella (P=0.020)、大肠杆菌志贺氏菌Escherichia-Shigella (P=0.0001)、鞘脂单胞菌Sphingomonas (P=0.0043)、类杆菌Bacteroides (P=0.0023)、涅斯捷连科氏菌Nesterenkonia (P=0.0130)及栖热菌Thermus (P=0.0084)在肠道内的相对丰度存在显著差异(图 5)。其中乳酸杆菌、Gilliamella、双歧杆菌、Snodgrassella 4种菌的相对丰度显著增加,不动杆菌、大肠杆菌志贺氏菌、鞘脂单胞菌、类杆菌、涅斯捷连科氏菌和栖热菌等6种菌的相对丰度显著减少。

|

| 图 5 不同日龄优势菌群分析 Figure 5 Analysis of the difference of dominant flora in different ages. |

2.5 高通量测序结果的qPCR验证

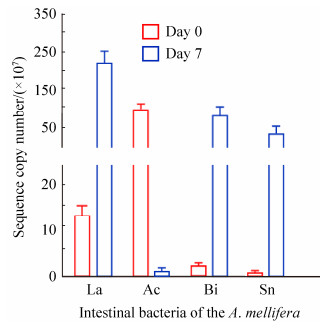

qPCR结果显示,Acinetobacter sp.的拷贝数在0日龄和7日龄分别为89.96×107和0.64×107;Snodgrassella alvi的拷贝数在0日龄和7日龄分别为0.023×107和54.14×107。Bifidobacterium的拷贝数在0日龄和7日龄分别为1.61×107和74.53×107,Lactobacillus的拷贝数在0日龄和7日龄分别为14.08×107和233.6×107。Acinetobacter sp.的相对丰度比为292.79,拷贝数比为140.56;Snodgrassella alvi的相对丰度比为2965.78,拷贝数比为2353.91;Bifidobacterium的相对丰度比为40.44,拷贝数比为46.29;Lactobacillus的相对丰度比为14.51,拷贝数比为16.5 (图 6),表明了工蜂肠道菌群高通量测序结果的可靠性。

|

| 图 6 工蜂肠道菌群高通量测序结果的qPCR验证 Figure 6 The qPCR validation of high-throughput sequencing results of gut flora of workers. La: Lactobacillus; Ac: Acinetobacter sp.; Bi: Bifidobacterium; Sn: Snodgrassella alvi. |

3 讨论

以往的研究大多聚焦于外源压力对肠道菌群的影响,昆虫肠道菌群的定殖规律却鲜为人知。因此,本研究通过Illumina测序技术对0日龄和7日龄西方蜜蜂成年工蜂肠道菌群16S rDNA高变区进行高通量测序,揭示了肠道菌群定殖起点和终点,肠道菌群多样性的差异,并初步描述了优势菌群相对丰度在定殖在两个龄期间的变化。

研究表明刚出房的西方蜜蜂工蜂肠道菌群较少[30],其通常在7日龄完成定殖[26]。因此,本研究选择刚出房的工蜂与肠道菌群定殖完成的工蜂,对这两个阶段肠道菌群的组成进行分析,以揭示肠道菌群定殖前后多样性和相对丰度的变化。有趣的是,0日龄工蜂肠道菌群的多样性比7日龄工蜂肠道菌群的多样性高。这个现象同在鱼类中的研究一致,即随着宿主的发育,鱼类肠道菌群的多样性显著降低[22, 31–32]。可见,在宿主的发育过程中,肠道菌群的多样性可能是一个降低的过程,这在昆虫和鱼类间是如此;当然该推论是否适用于其他动物类群,还需要进一步的研究。此外,本研究发现,0日龄的幼蜂肠道内缺乏核心菌群,这与先前的报道一致[33],进一步证实了0日龄工蜂肠道菌群内缺乏核心菌群。对于0日龄的幼蜂为何缺乏核心菌群,研究者报道了多种可能的原因。例如,Powell等(2014)提出工蜂的核心菌群是通过社会接触(与蜂房内其他蜂群进行接触)获得的,而刚出房的幼蜂未与其他工蜂进行接触,这可能是导致0日龄工蜂缺乏核心菌群的原因之一。另外,7日龄的工蜂在蜂房内主要充当护士蜂的角色,将分泌的各种蛋白饲喂幼虫和年老的工蜂[34–36],而刚出房的幼蜂并未行使社会责任,社会分工可能也刺激了核心菌群的产生。

0日龄工蜂的肠道内主要以变形菌门为主,而其他昆虫中变形菌门也是主要的肠道菌群之一[37],这些结果表明变形菌门在昆虫肠道内占主要优势可能是昆虫肠道菌群组成的一个鲜明特征。当然,这个推测还需要通过对更多的昆虫类群肠道菌群进行分析归纳予以证实。此外,0日龄工蜂肠道内优势菌丰度依次为厚壁菌门、放线菌门、拟杆菌门,这和光肩星天牛(Anoplophora glabripennis)肠道内门分类水平菌群的丰度一致[38],表明工蜂和光肩星天牛两种昆虫肠道的组成高度类似,我们初步推测这可能是昆虫肠道菌群所特有的组成形式。在属分类水平上,0日龄工蜂肠道内主要优势菌为不动杆菌属,该属广泛存在于其他昆虫肠道内,具有协助宿主消化食物和进行氮素转化的功能[39],是一类重要的昆虫肠道益生菌,不动杆菌属促进刚出房幼蜂肠道对食物的消化吸收。因此,不动杆菌属值得进一步研究开发,有望作为一类西方蜜蜂成年工蜂幼蜂的食物添加益生菌,提高工蜂品质。但是,7日龄的工蜂肠道内主要优势菌群中缺乏不动杆菌,被乳酸杆菌、Gilliamella、双歧杆菌、Snodgrassella等4个属取代,这4个属也有研究表明是蜜蜂肠道内主要优势菌群[40],表明西方蜜蜂肠道菌群的定殖是一个菌群种类不断更替的动态过程。乳酸杆菌和双歧杆菌可促进宿主对营养吸收和对病原体的免疫。例如,研究者将蜂粮中分离的乳酸杆菌和双歧杆菌菌液喷洒到蜂房中[41],可显著提高蜂蜜的产量。可见,工蜂肠道内的菌群在宿主的生命活动中扮演了更为多样和丰富的角色,不局限于帮助宿主吸收及利用食物。工蜂在0日龄到7日龄期间,表现出了快速的发育特征,而有研究表明双歧杆菌可刺激宿主产生激素,从而促进工蜂的发育[42]。本研究中,7日龄西方蜜蜂工蜂同0日龄相比较,发现双歧杆菌在肠道内相对丰度显著增加,表明双歧杆菌具有成为指示宿主快速发育的一个潜在生物标记。

总之,本研究是首次采用高通量测序技术对蜜蜂肠道菌群定殖规律进行探索,我们选取西方蜜蜂成年工蜂肠道菌群定殖的两个关键时间节点对其肠道菌群的多样性和优势菌的相对丰度进行分析。我们的结果表明,7日龄工蜂肠道菌群的多样性显著高于0日龄工蜂。进一步地,在2个日龄间,各分类单元中,肠道菌群的相对丰度也随菌群定殖的完成表现出差异。特别是不动杆菌等其他非核心菌群相对丰度降低和核心菌群相对丰度增高。本研究结果将为研究蜜蜂乃至其他昆虫的肠道菌群定殖规律提供一些新的启发。当然,西方蜜蜂肠道菌群定殖是一个动态的过程,本研究仅选取其中2个时间点,这对全面解析其定殖规律显然是不够的,也丢失了肠道菌群在定殖过程中的动态变化信息。因此,在未来的研究中将密集采集更多的时间点,探索西方蜜蜂肠道菌群定殖的高分辨率的动态定殖规律。

| [1] |

Yu YS, Zhang XW, Luo K. Key technology of Apis mellifare breeding. Practical Rural Technology, 2008(1): 44.

(in Chinese) 余玉生, 张学文, 罗坤. 西方蜜蜂养殖关键技术. 农村实用技术, 2008(1): 44. |

| [2] | West-Eberhard M. Phenotypic plasticity and the origins of diversity. Annual Review of Ecology and Systematics, 1989, 20: 249-278. DOI:10.1146/annurev.es.20.110189.001341 |

| [3] | Stokstad E. The case of the empty hives. Science, 2007, 316(5827): 970-972. DOI:10.1126/science.316.5827.970 |

| [4] | Becher MA, Osborne JL, Thorbek P, Kennedy PJ, Grimm V. REVIEW:towards a systems approach for understanding honeybee decline:a stocktaking and synthesis of existing models. Journal of Applied Ecology, 2013, 50(4): 868-880. DOI:10.1111/1365-2664.12112 |

| [5] | Godfray HCJ, Blacquière T, Field LM, Hails RS, Petrokofsky G, Potts SG, Raine NE, Vanbergen AJ, Mclean AR. A restatement of the natural science evidence base concerning neonicotinoid insecticides and insect pollinators. Proceedings of the Royal Society B:Biological Sciences, 2014, 281(1786): 20140558. DOI:10.1098/rspb.2014.0558 |

| [6] | Bäckhed F, Manchester JK, Semenkovich CF, Gordon JI. Mechanisms underlying the resistance to diet-induced obesity in germ-free mice. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 2007, 104(3): 979-984. DOI:10.1073/pnas.0605374104 |

| [7] | Lin LM, Xie F, Sun DM, Liu JH, Zhu WY, Mao SY. Ruminal microbiome-host crosstalk stimulates the development of the ruminal epithelium in a lamb model. Microbiome, 2019, 7(1): 83. DOI:10.1186/s40168-019-0701-y |

| [8] | Tremaroli V, Bäckhed F. Functional interactions between the gut microbiota and host metabolism. Nature, 2012, 489(7415): 242-249. DOI:10.1038/nature11552 |

| [9] | Pickard JM, Zeng MY, Caruso R, Núñez G. Gut microbiota:role in pathogen colonization, immune responses, and inflammatory disease. Immunological Reviews, 2017, 279(1): 70-89. DOI:10.1111/imr.12567 |

| [10] | Castellanos JG, Longman RS. Innate lymphoid cells link gut microbes with mucosal T cell immunity. Gut Microbes, 2020, 11(2): 231-236. DOI:10.1080/19490976.2019.1638725 |

| [11] | Kwong WK, Moran NA. Cultivation and characterization of the gut symbionts of honey bees and bumble bees:description of Snodgrassella alvi gen. nov., sp. nov., a member of the family Neisseriaceae of the Betaproteobacteria, and Gilliamella apicola gen. nov., sp. nov., a member of Orbaceae fam. nov., Orbales ord. nov., a sister taxon to the order 'Enterobacteriales' of the Gammaproteobacteria. International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology, 2013, 63(6): 2008-2018. DOI:10.1099/ijs.0.044875-0 |

| [12] | Babendreier D, Joller D, Romeis J, Bigler F, Widmer F. Bacterial community structures in honeybee intestines and their response to two insecticidal proteins. FEMS Microbiology Ecology, 2007, 59(3): 600-610. DOI:10.1111/j.1574-6941.2006.00249.x |

| [13] | Bottacini F, Milani C, Turroni F, Sánchez B, Foroni E, Duranti S, Serafini F, Viappiani A, Strati F, Ferrarini A, Delledonne M, Henrissat B, Coutinho P, Fitzgerald GF, Margolles A, van Sinderen D, Ventura M. Bifidobacterium asteroides PRL2011 genome analysis reveals clues for colonization of the insect gut. PLoS One, 2012, 7(9): e44229. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0044229 |

| [14] | Engel P, Kwong WK, Moran NA. Frischella perrara gen. nov., sp. nov., a gammaproteobacterium isolated from the gut of the honeybee, Apis mellifera. International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology, 2003, 63(10): 3646-3651. |

| [15] | Jeyaprakash A, Hoy MA, Allsopp MH. Bacterial diversity in worker adults of Apis mellifera capensis and Apis mellifera scutellata (Insecta:Hymenoptera) assessed using 16S rRNA sequences. Journal of Invertebrate Pathology, 2003, 84(2): 96-103. DOI:10.1016/j.jip.2003.08.007 |

| [16] | Fouhy F, Ross RP, Fitzgerald GF, Stanton C, Cotter PD. Composition of the early intestinal microbiota:knowledge, knowledge gaps and the use of high-throughput sequencing to address these gaps. Gut Microbes, 2012, 3(3): 203-220. DOI:10.4161/gmic.20169 |

| [17] | Jones JC, Fruciano C, Hildebrand F, Al Toufalilia H, Balfour NJ, Bork P, Engel P, Ratnieks FLW, Hughes WO. Gut microbiota composition is associated with environmental landscape in honey bees. Ecology and Evolution, 2018, 8(1): 441-451. DOI:10.1002/ece3.3597 |

| [18] | Motta EVS, Raymann K, Moran NA. Glyphosate perturbs the gut microbiota of honey bees. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 2018, 115(41): 10305-10310. DOI:10.1073/pnas.1803880115 |

| [19] | Huang SK, Ye KT, Huang WF, Ying BH, Su X, Lin LH, Li JH, Chen YP, Li JL, Bao XL, Hu JZ. Influence of feeding type and Nosema ceranae infection on the gut microbiota of Apis cerana workers. mSystems, 2018, 3(6): e00177-18. DOI:10.1101/375576 |

| [20] | Robertson RC, Manges AR, Finlay BB, Prendergast AJ. The human microbiome and child growth-first 1000 days and beyond. Trends in Microbiology, 2019, 27(2): 131-147. DOI:10.1016/j.tim.2018.09.008 |

| [21] | Li XH, Zhou L, Yu YH, Ni JJ, Xu WJ, Yan QY. Composition of gut microbiota in the gibel carp (Carassius auratus gibelio) varies with host development. Microbial Ecology, 2017, 74(1): 239-249. DOI:10.1007/s00248-016-0924-4 |

| [22] | Stephens WZ, Burns AR, Stagaman K, Wong S, Rawls JF, Guillemin K, Bohannan BJM. The composition of the zebrafish intestinal microbial community varies across development. The ISME Journal, 2016, 10(3): 644-654. DOI:10.1038/ismej.2015.140 |

| [23] | Costa MC, Stämpfli HR, Allen-Vercoe E, Weese JS. Development of the faecal microbiota in foals. Equine Veterinary Journal, 2016, 48(6): 681-688. DOI:10.1111/evj.12532 |

| [24] | Zhang ZM, Li DP, Refaey MM, Xu WT, Tang R, Li L. Host Age affects the development of southern Catfish gut bacterial community divergent from that in the food and rearing water. Frontiers in Microbiology, 2018, 9: 495. DOI:10.3389/fmicb.2018.00495 |

| [25] | Powell JE, Martinson VG, Urban-Mead K, Moran NA. Routes of acquisition of the gut microbiota of the honey bee Apis mellifera. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 2014, 80(23): 7378-7387. DOI:10.1128/AEM.01861-14 |

| [26] | Anderson KE, Rodrigues PAP, Mott BM, Maes P, Corby-Harris V. Ecological succession in the honey bee gut:shift in Lactobacillus strain dominance during early adult development. Microbial Ecology, 2016, 71(4): 1008-1019. DOI:10.1007/s00248-015-0716-2 |

| [27] | Wang LH, Wu J, Li K, Sadd BM, Guo YL, Zhuang DH, Zhang ZY, Chen Y, Evans JD, Guo J, Zhang ZG, Li JL. Dynamic changes of gut microbial communities of bumble bee queens through important life stages. mSystems, 2019, 4(6): e00631-19. DOI:10.1128/mSystems.00631-19 |

| [28] | Li JL, Qin HR, Wu J, Sadd BM, Wang XH, Evans JD, Peng WJ, Chen YP. The prevalence of parasites and pathogens in Asian honeybees Apis cerana in China. PLoS One, 2012, 7(11): e47955. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0047955 |

| [29] |

Wang TZ, Wang ZL, Zhu HF, Wang ZY, Yu XP. Analysis of the gut microbial diversity of the brown planthopper, Nilaparvata lugens (Hemiptera:Delphacidae) by high-throughput sequencing. Acta Entomologica Sinica, 2019, 62(3): 323-333.

(in Chinese) 王天召, 王正亮, 朱杭锋, 王紫晔, 俞晓平. 基于高通量测序的褐飞虱肠道微生物多样性分析. 昆虫学报, 2019, 62(3): 323-333. |

| [30] | Martinson VG, Moy J, Moran NA. Establishment of characteristic gut bacteria during development of the honeybee worker. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 2012, 78(8): 2830-2840. DOI:10.1128/AEM.07810-11 |

| [31] | Wilkins LGE, Rogivue A, Fumagalli L, Wedekind C. Declining diversity of egg-associated bacteria during development of naturally spawned whitefish embryos (Coregonus spp.). Aquatic Sciences, 2015, 77(3): 481-497. DOI:10.1007/s00027-015-0392-9 |

| [32] | Yan QY, Li JJ, Yu YH, Wang JJ, He ZL, Van Nostrand JD, Kempher ML, Wu LY, Wang YP, Liao LJ, Li XH, Wu S, Ni JJ, Wang C, Zhou JZ. Environmental filtering decreases with fish development for the assembly of gut microbiota. Environmental Microbiology, 2016, 18(12): 4739-4754. DOI:10.1111/1462-2920.13365 |

| [33] | Yun JH, Jung MJ, Kim PS, Bae JW. Social status shapes the bacterial and fungal gut communities of the honey bee. Scientific Reports, 2018, 8(1): 2019. DOI:10.1038/s41598-018-19860-7 |

| [34] | Crailsheim K. The flow of jelly within a honeybee colony. Journal of Comparative Physiology B, 1992, 162(8): 681-689. DOI:10.1007/BF00301617 |

| [35] | Crailsheim K. Interadult feeding of jelly in honeybee (Apis mellifera L.) colonies. Journal of Comparative Physiology B, 1991, 161(1): 55-60. DOI:10.1007/BF00258746 |

| [36] | Seeley TD. Adaptive significance of the age polyethism schedule in honeybee colonies. Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology, 1982, 11(4): 287-293. DOI:10.1007/BF00299306 |

| [37] | Yun JH, Roh SW, Whon TW, Jung MJ, Kim MS, Park DS, Yoon C, Nam YD, Kim YJ, Choi JH, Kim JY, Shin NR, Kim SH, Lee WJ, Bae JW. Insect gut bacterial diversity determined by environmental habitat, diet, developmental stage, and phylogeny of host. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 2014, 80(17): 5254-5264. DOI:10.1128/AEM.01226-14 |

| [38] | Schloss PD, Delalibera I Jr, Handelsman J, Raffa KF. Bacteria Associated with the guts of two wood-boring beetles:Anoplophora glabripennis and Saperda vestita (Cerambycidae). Environmental Entomology, 2006, 35(3): 625-629. DOI:10.1603/0046-225X-35.3.625 |

| [39] | Briones-Roblero CI, Rodríguez-Díaz R, Santiago-Cruz JA, Zúñiga G, Rivera-Orduña FN. Degradation capacities of bacteria and yeasts isolated from the gut of Dendroctonus rhizophagus (Curculionidae:Scolytinae). Folia Microbiologica, 2016, 62(1): 1-9. DOI:10.1007/s12223-016-0469-4 |

| [40] | Guo J, Wu J, Chen YP, Evans JD, Dai RG, Luo WH, Li JL. Characterization of gut bacteria at different developmental stages of Asian honey bees, Apis cerana. Journal of Invertebrate Pathology, 2015, 127: 110-114. DOI:10.1016/j.jip.2015.03.010 |

| [41] | Alberoni D, Baffoni L, Gaggìa F, Ryan PM, Murphy K, Ross PR, Stanton C, Di Gioia D. Impact of beneficial bacteria supplementation on the gut microbiota, colony development and productivity of Apis mellifera L. Beneficial Microbes, 2018, 9(2): 269-278. DOI:10.3920/BM2017.0061 |

| [42] | Kešnerová L, Mars RAT, Ellegaard KM, Troilo M, Sauer U, Engel P. Disentangling metabolic functions of bacteria in the honey bee gut. PLoS Biology, 2017, 15(12): e2003467. DOI:10.1371/journal.pbio.2003467 |

2020, Vol. 60

2020, Vol. 60