中国科学院微生物研究所,中国微生物学会,中国菌物学会

文章信息

- 刘利玲, 李会琳, 蒙振思, 彭进友, 李晓东, 彭超, 路璐, 胥晓. 2020

- Liling Liu, Huilin Li, Zhensi Meng, Jinyou Peng, Xiaodong Li, Chao Peng, Lu Lu, Xiao Xu. 2020

- 青杨雌雄株叶际微生物群落多样性和结构的差异

- Differences in phyllosphere microbial communities between female and male Populus cathayana

- 微生物学报, 60(3): 556-569

- Acta Microbiologica Sinica, 60(3): 556-569

-

文章历史

- 收稿日期:2019-05-23

- 修回日期:2019-07-15

- 网络出版日期:2019-07-26

2. 西华师范大学环境科学院, 四川 南充 637009;

3. 小五台山国家级自然保护区, 河北 蔚县 075700

2. College of Environmental Science and Engineering, China West Normal University, Nanchong 637009, Sichuan Province, China;

3. Xiaowutai Mountains National Nature Reserve, Yuxian 075700, Hebei Province, China

植物的叶片不仅通过光合作用为植物生长提供所需碳水化合物,同时也是一个独立的微环境域,其上也寄居着大量的微生物,包括细菌、真菌等,这些微生物称为叶际微生物(phyllosphere microorganisms)[1-3]。植物的叶面营养物质和水资源相对匮乏,且面临着紫外线照射、温差过大和存在活性氧等不利因素。即便如此,据统计,地球上叶际微生物的总数超过1026个细胞,平均数量是106-107 cell/cm2[4-5]。叶际微生物在全球碳氮循环中起着重要作用,且与植物宿主的关系十分复杂,多数是共生关系[6]。叶际微生物具有多种功能,如固氮[7-8]、促进植物生长[9-10]、抑制病原微生物[9]、降解环境污染物[11]等方面有重要作用,当然也有引发植物病害等负面作用。目前研究表明,不同植物的叶际微生物群落结构存在显著差异,同一物种在不同地区的植物叶际微生物群落也存在差异[12-13]。然而,目前大多数关于叶际微生物的研究都是关于农作物以及雌雄同株植物,对于雌雄异株植物这一特殊群体的叶际微生物菌群的研究却甚少。

雌雄异株植物由959个属14620种被子植物组成[14],其中青杨(Populus cathayana)是常见的雌雄异株植物,广泛分布于温带,在造林和生态保护中起着重要作用[15]。一直以来,雌雄异株植物的差异性是植物学家的研究热点。关于雌雄间的形态[16]、资源分配[17]、生殖分配[18]、压力适应能力[19],胁迫条件下的养分有效性的差异性已被广泛研究[15]。研究发现,青杨雌雄株在叶片形态、叶绿素含量、气孔分布、叶片衰老速度、净光合速率、抗压能力等方面存在着差异[20-23]。青杨雄株具有更有效的抗氧化系统,花青素含量较高,可缓解UV-B辐射,较雌性具有更好的自我保护机制[24]。此外,影响叶际微生物群落的环境影响因素因子一直是叶际微生物研究的热点之一。有研究表明,植物叶片性质是影响叶际微生物群落结构的关键因素[25]。例如,不同的植物叶片特征如气孔、水腺、叶片厚度、营养成分(碳、磷、可溶性糖含量)、含水量等影响着叶际微生物的定殖[26-28]。虽然上述研究证实了雌雄株在形态以及生理代谢方面有差异,但这些差异是否会引起雌雄株叶际微生物的差异仍不清楚,影响雌雄异株植物的叶际微生物群落结构的主导因素的研究也还很缺乏。因此,我们推测青杨雌雄株的叶际微生物菌群存在着差异,然而,相关的研究并未见报道。

综上,本研究以中国河北小五台山的天然青杨林为研究对象,采用基于16S rRNA/ITS1基因的MiSeq高通量测序技术对叶际细菌和真菌进行测序,探究青杨雌雄株间叶际细菌和真菌群落结构的差异性,并与叶片理化性质耦合分析揭示影响叶际微生物的主导因子。该研究成果为深入理解叶际微生物与雌雄异株植物之间的关系提供新的研究思路。

1 材料和方法 1.1 采样点描述与叶片采集采样点位于河北小五台自然保护区(39°50-40°07′ N, 114°47′-115°30' E),海拔1142-2882 m。该地区属暖温带季风气候,年平均气温为7.1 ℃,年降水量为528 mm。土壤类型主要为褐土、山地棕壤及亚高山草甸土。青杨种群分布于小五台山西台河谷两岸,在1400-1700 m海拔区域形成纯林,林分条件为天然次生林。叶片采集选择无雨、雾、露的时间为2017年9月22日,选取小五台山的海拔1500-1600 m处,分别取8棵不同的雌性和雄性青杨树,共16棵。所选青杨生境相似,生长茂盛,林冠大小相似,树龄30年以上,高约20-25 m。两棵树的间距为200-300 m,树的性别在开花季节鉴定,并做标记。选定每棵树离地面10 m高度的3个方向(东面,西南面,西北面)的枝干,戴上无菌手套平均采摘3个枝干上的完整、无病虫害斑点的叶片共50-100 g,装入灭菌的封口袋内,冰盒4 ℃保存,带回实验室后储存于-20 ℃冰箱中,用于后续的分析。

1.2 叶片理化性质测定鲜叶5 g切碎磨成匀浆,加入30 mL去离子水,超声波振动2 h后过滤用pH计(Mettler-Toledo Instruments Co.Ltd., Shanghai, China)测定叶片pH值。叶片在70 ℃下烘干至恒重,称量干重,计算相对含水量。把烘干的叶片磨碎过筛(100目),用碳氮分析仪(Elementar-TOC & Water Analysis, Germany)测定叶片全碳,利用全自动间断化学分析仪(CleverChem 200+,Hamburg,Germany)对叶片总氮和总磷含量分析测定。取烘干叶片粉末约20 mg于10 mL离心管中,加入4 mL 80%乙醇,80 ℃水浴30 min左右,期间晃动几次,5000×g离心5 min后,转移上清液,再在沉淀中加入2 mL 80%乙醇,5000×g离心5 min后,转移上清液,最后在沉淀中加入2 mL 80%乙醇,7000×g离心3 min后,转移上清液,合并上清液(定容到8 mL),用于可溶性总糖测定。沉淀中加入2 mL蒸馏水在沸水浴中15 min后,加入1 mL 9.2 mol/L高氯酸溶液,不断晃动15 min后,加入1 mL蒸馏水,混匀,5000×g离心5 min后,上清液转移;沉淀中加入2 mL 4.6 mol/L高氯酸,晃动15 min后,加入2 mL蒸馏水,5000×g离心5 min。合并上清液(约8 mL),用于淀粉的测定。

1.3 叶片微生物DNA提取从叶片中收集微生物细胞参考Kembel等[28]、Ren等[29]和孙泓等的提取方法[30]。称取叶片样品10 g剪碎放入无菌三角瓶中,加入1:20 (叶重/体积TE缓冲液=1:20)无菌TE缓冲液(10 mmol/L Tris-HCl, 1 mmol/L EDTA, pH 8.0),用灭菌膜封口后于室温下在200 r/min的摇床上振荡30 min,将微生物细胞从叶片表面分离,振荡后的叶片在40 kHz超声15 min,在无菌环境中使用真空抽滤装置将振荡液中的微生物收集到0.22 μm的滤膜上,使用Fast DNA spin kit试剂盒(Qbiogene, Irvine, CA)提取滤膜上的总DNA。按照试剂盒说明书提取DNA,将提取到的DNA溶解于100 μL的ddH2O,保存于-20 ℃。

1.4 16S rRNA/ITS基因的高通量测序使用Illumina Miseq测序平台对16个样品的细菌16S rRNA基因的V4-V5区和真菌ITS1 rDNA基因的ITS1区进行测序,细菌和真菌的测序总个数为32个。扩增细菌引物为515F:(5′-GTGCCAGCM GCCGCGGTAA-3′),907R:(5′-CCGTCAATTCMTT TRAGTTT-3′)[29];真菌引物为ITS5F:GGAAGTAA AAGTCGTAACAAGG,ITS1R:GCTGCGTTCTT CATCGATGC[31]。再将扩增产物用1.8%琼脂糖凝胶电泳检测PCR产物纯化效果,测定纯化后PCR产物的浓度,将纯化产物等摩尔数混合,以备上机前纯化和测序仪分析。

1.5 统计和分析运用SPSS 18.0软件,对雌雄叶片理化性质和多样性指数使用单因素方差检验进行比较。统计分析测序结果用QIIME、Mothur、Canoco进行分析。运用QIIME软件(Quantitative Insights Into Microbial Ecology,v1.8.0)进行序列过滤,以保证分析结果准确性。去除叶绿体来源和线粒体来源的序列。运用Mothur软件中UCHIME的方法去除嵌合体序列,得到后续分析的优质序列。使用QIIME软件,调用UCLUST这一序列比对工具,对获得的序列按97%的序列相似度进行归并和OTU划分,获得每个OTU所对应的分类学信息[32]。并使用QIIME软件计算Alpha多样性指数。用Canoco软件对环境因子对群落结构的影响做RDA分析。使用Mothur软件,调用Metastats[33]的统计学算法,对门、属水平的各个分类单元在雌雄之间的序列量(即绝对丰度)差异进行两两比较检验。画图采用OriginPro 8.0制作。

1.6 NCBI序列号本研究中细菌和真菌的核苷酸序列分别以序列号SRR8640871-SRR8640886和SRR8653756-SRR8653771存入在GenBank里。

2 结果和分析 2.1 青杨雌雄叶片的理化性质雌雄株叶片的理化性质如表 1所示。共测定了7个指标包括pH、含水量(moisture content)、全碳(total carbon, TC)、全氮(total nitrogen, TN)、全磷(total phosphorus, TP)、淀粉(starch)和可溶性糖(soluble sugar)都无显著差异(P > 0.05)。

| Properties | F | M |

| pH | 5.93±0.15a | 5.83±0.13a |

| Moisture content/% | 66.52±1.07a | 63.88±3.17a |

| TC/(mg/g) | 417.83±6.70a | 424.32±14.67a |

| TN/(mg/g) | 31.00±5.28a | 24.20±6.86a |

| TP/(mg/g) | 1.99±0.70a | 2.07±0.85a |

| Starch/(μg/mg) | 75.06±23.99a | 84.52±24.09a |

| Soluble sugar/(μg/mg) | 28.28±6.50a | 43.82±13.54a |

| F and M represent female and male P. cathayana, respectively. Different letters following values within the same lines indicate significant differences between females and males (P < 0.05). | ||

2.2 青杨雌雄叶际微生物群落的丰富度和多样性

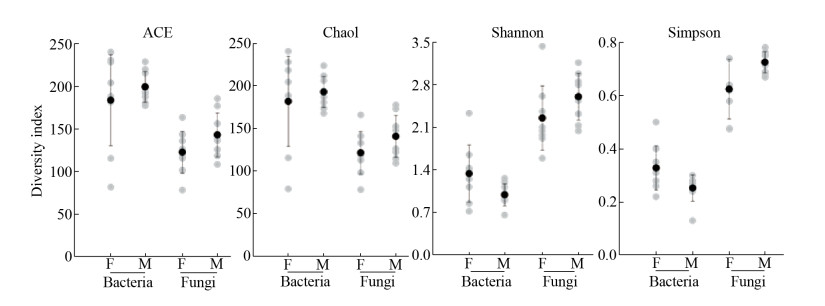

8个雌雄株重复叶际细菌分别获得有效序列为407390和517855,叶际真菌的有效序列分别为385429和452960。采用97%的序列相似度作为OTU (Operational Taxonomic Unit,OTUs)的划分阈值。稀释曲线显示,叶片细菌和真菌随着测序数量的增加,OTU数量趋于稳定,表明青杨叶片细菌和真菌种群测序深度满足多样性分析要求。比较雌雄叶片的Chao 1、ACE、Simpson、Shannon多样性指数(图 1),发现雌雄叶际细菌和真菌群落均无显著差异(P > 0.05)。

|

| 图 1 雌雄株叶际细菌和真菌的多样性指数 Figure 1 The diversity indexes of bacteria and fungi communities in the phyllosphere of female and male P. cathayana. Each group was conducted in eight repetitions. The error bars represent the standard errors of the mean of the eight repetitions. |

2.3 青杨雌雄叶际细菌群落组成

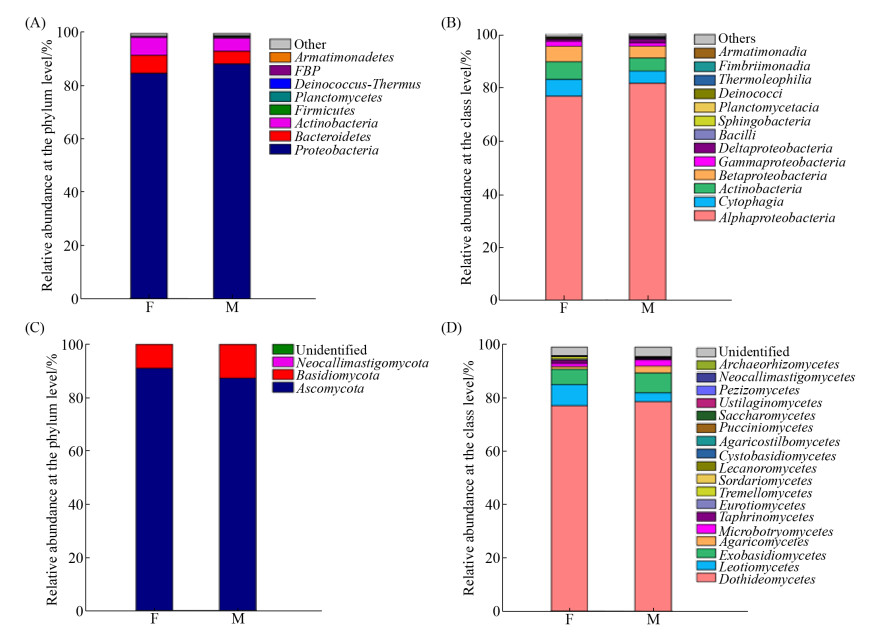

测序结果表明,青杨主导叶际细菌隶属于8个门、13个纲、25个目、35个科、50个属。如图 2-A,主要为变形菌门(Proteobacteria)、拟杆菌门(Bacteroidetes)、放线菌门(Actinobacteria)、厚壁菌门(Firmicutes)和浮霉菌门(Planctomycetes),隶属于上述5个门的细菌OTUs之和分别占雌株和雄株细菌总OTUs数量的98.86%和98.98%。其中,Proteobacteria的相对丰度最高,其OTUs数量分别占雌雄株叶际细菌总OTUs数量的85.16%和88.62%。Bacteroidetes和Actinobacteria次之。经Metastats两两比较检验表明,在门水平上,雌雄株的各个细菌门相对丰度无显著差异(P > 0.05)。

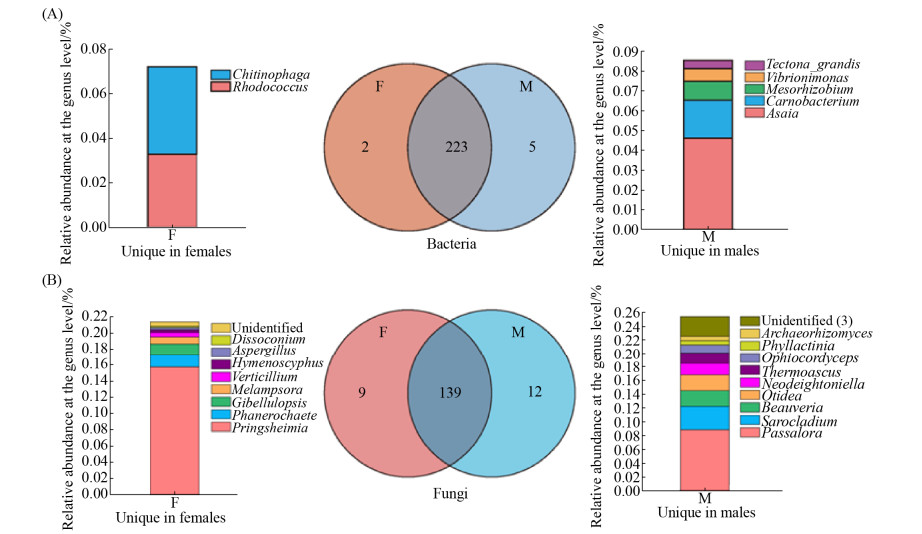

如图 2-B,在纲水平,α-变形菌纲(Alphaproteobacteria)为主导纲,在雌雄株叶际中丰度各为76.69%和81.56%。分析表明,雌雄株细菌菌群无显著差异的纲。在属水平上,雌雄株叶际主导属为薄层杆属(Hymenobacter)、鞘氨醇单胞菌属(Sphingomonas)、甲基杆菌属(Methylobacterium)。基于总OTUs数据分析,雌株叶片独有的细菌OTUs隶属于红球菌属(Rhodococcus) (0.03%)和鞘氨醇杆菌属(Chitinophaga) (0.04%),雄株叶片独有的细菌OTUs隶属于5个属,Asaia (0.05%)、肉食杆菌属(Carnobacterium) (0.02%)等,其余3个属的相对丰度小于0.01% (图 3-A)。如图 4-A,针对相对丰度大于0.1%的属,Metastats差异分析表明Sphingomonas在雌株叶际的相对丰度(13.46%)显著低于雄株(23.07%) (P < 0.05)。此外,Amnibacterium的相对丰度在雌雄株间也存在着显著差异(P < 0.05),雌株(2.55%)显著高于雄株(1.45%)。

|

| 图 3 雌雄株共有和独有的细菌(A)和真菌(B) OTUs Figure 3 The shared and unique bacteria (A) and fungi (B) OTUs between female and male P. cathayana. F and M represent female and male P. cathayana, respectively. |

2.4 青杨雌雄叶际真菌群落组成

测序结果表明,青杨主导叶际真菌隶属于3个门、18个纲、24个目、25个科、44个属。如图 2-C,在门水平,主要为子囊菌门(Ascomycota)、担子菌门(Basidiomycota),隶属于这2个门的真菌OTUs之和,分别占雌株和雄株真菌总OTUs数量的99.95%和99.94%。其中Ascomycota的相对丰度最高,其OTUs数量分别占雌雄株叶际真菌总OTUs数量的90.95%和87.28%。Metastats两两比较检验表明,在门水平上,雌雄株的各个真菌门的相对丰度无显著差异(P > 0.05)。如图 2-D,在纲水平,子囊菌门的座囊菌纲(Dothideomycetes)为主导纲,在雌雄株叶际中的相对丰度分别为78.04%和79.59%。分析表明,伞菌纲(Agaricomycetes)的相对丰度在雌雄株间存在显著差异(P < 0.05),雄株(2.61%)高出雌株(0.98%) 1.6倍。

在属水平,青杨雌雄株叶际主导属为小麦叶枯菌属(Zymoseptoria)、黑星菌属(Venturia)、茎点霉属(Phoma)和白粉菌属(Erysiphe)。如图 3-B,青杨雌株叶片独有的真菌OTUs隶属于9个属,有Pringsheimia (0.15%)等,其余的丰度都小于0.1%。雄株叶片独有的真菌OTUs隶属于12个属,有钉孢属(Passalora) (0.009%)、帚枝霉属(Sarocladium) (0.003%)、白僵菌属(Beauveria) (0.002%)等。如图 4-B,Metastats差异分析表明,雌雄株叶际有6个真菌属的相对丰度存在显著差异。其中榆孔菌属(Elmerina)在雌株(0.15%)中的相对丰度低于雄株(0.32%) (P < 0.05),短梗霉属(Aureobasidium) (0.28%,0.10%)、红酵母属(Rhodotorula) (0.44%,0.13%)、Endoconidioma (0.06%,0.03%)、链核盘菌属(Monilinia) (0.07%,0.001%)和外担子菌属(Exobasidium) (0.04%,0.002%)都是在雌株中的相对丰度显著高于雄株(P < 0.05)。

|

| 图 4 基于Metastats两两比较,雌雄株有显著差异的细菌(A)和真菌(B)属 Figure 4 Taxon relative abundance of bacterial (A) and fungal (B) genera that were significantly different between the phyllosphere of female and male P. cathayana (P < 0.05). |

2.5 叶片理化性质与微生物群落结构的相关性分析

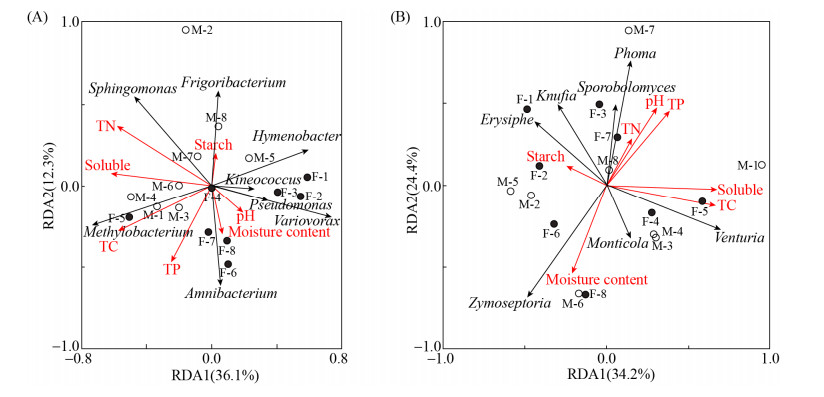

利用雌雄株叶际微生物在属水平的群落相对丰度和7个叶片理化因子做冗余分析(Redundancy analysis, RDA)。该RDA分析针对所有16个青杨叶际样品数据与环境因子进行耦合分析,不考虑雌雄株的区分。如图 5-A所示,叶际细菌第一排序轴和第二排序轴的特征值分别为36.1%和12.3%,解释了细菌菌群结构变化总方差值的48.4%。RDA表明,pH、含水量、全碳、全氮、全磷、可溶性糖、淀粉等7个叶片理化因子与青杨叶际细菌群落结构变化无显著相关性(表 2)。叶际真菌第一排序轴和第二排序轴的特征值分别为34.2%和24.4%,解释了真菌菌群变化总方差值的58.6%。RDA表明,叶片含水量对青杨叶际真菌群落结构变化的分布有显著影响(P < 0.05)。此外,叶片含水量与真菌Zymoseptoria和Monticola这两个属的相对丰度呈现显著正相关(P < 0.05)。

|

| 图 5 基于RDA分析叶际细菌(A)和叶际真菌(B)与叶片理化性质的关系 Figure 5 Redundancy analysis based on the phyllosphere bacterial (A) and fungal (B) community structure and leaves physicochemical variables. |

| Parameters | Eigen value | Variation explains solely/% | F value | P value |

| Bacteria | ||||

| pH | 0.08 | 8 | 1.59 | 0.1780 |

| Moisture content | 0.04 | 4 | 0.75 | 0.5220 |

| TC | 0.14 | 14 | 2.49 | 0.0880 |

| TN | 0.05 | 5 | 0.98 | 0.3800 |

| TP | 0.07 | 7 | 1.35 | 0.2580 |

| Starch | 0.02 | 2 | 0.26 | 0.8960 |

| Soluble sugar | 0.04 | 4 | 0.75 | 0.5220 |

| Fungi | ||||

| pH | 0.09 | 9 | 1.75 | 0.1760 |

| Moisture content | 0.14 | 14 | 3.24 | 0.0140 |

| TC | 0.16 | 16 | 2.57 | 0.0800 |

| TN | 0.05 | 5 | 1.28 | 0.2940 |

| TP | 0.02 | 2 | 0.42 | 0.7160 |

| Starch | 0.01 | 1 | 0.17 | 0.9080 |

| Soluble sugar | 0.16 | 16 | 3.03 | 0.0540 |

3 讨论

在本研究中,我们发现青杨雌雄株的总体叶际微生物群落丰富度和多样性指数无显著性差异,而在属水平雌雄株间存在着相对丰度有显著差异的细菌和真菌,且雌雄株都有其各自特有的菌群。同时,叶片含水量和叶际真菌群落结构有显著相关性。这些结果将有助于我们认识雌雄异株植物叶际微生物的差异性,以及深入了解叶片性质与叶际微生物之间的关系。

雌雄青杨叶际微生物的多样性指数没有显著差异,可能与同种植物相似的生理代谢和性状相关。植物基因型在决定植物叶际微生物群落结构方面起着重要的作用[25, 34]。Smets等[35]在研究常春藤的叶际微生物中发现,不同生境中的常春藤叶际细菌多样性指数并未表现出显著性差异。Redford等[36]通过对松树叶际细菌群落组成的分析发现,即使在较大的地理距离范围内,同一植物种内的细菌群落分化极小。除了植物种类、空间位置、叶的生长期等能够影响叶际细菌群落结构外,不同的叶片结构、化学组成和分泌物会影响叶际微生物群落结构组成[37-39]。本研究中测得的青杨雌雄叶片的理化性质无显著性差异,这与Wu等[40]的研究结果一致,因此,这可能是雌雄株微生物菌群多样性指数无显著差异的原因。

在门水平,Proteobacteria在叶际细菌群落的优势地位已被大量的研究所证实[6, 27, 34, 36-37]。隶属于Alphaproteobacteria的Sphingomonas在青杨雄株叶片上的相对丰度显著高于在雌株叶片上的(P < 0.05)。Sphingomonas作为叶际细菌的优势属,可以防紫外线辐射,在拟南芥、水稻、白玉兰等很多植物的叶际细菌群落研究中也有报道[6, 41]。对从植物叶际分离出的Sphingomonas phyllosphaerae菌株研究发现其可显著降低病原菌的生长,增强对叶片致病菌的抵御能力[42]。同时,Sphingomonas paucimobilis菌株还可以通过降解有机物污染[43],进而降低污染物对叶片生长的影响。此外,Delmotte还检测到Sphingomonas具有与环境胁迫反应相关的调节因子,如具有抗环境胁迫的调节因子PhyR和EcfG,因此,叶面上的Sphingomonas有助于提高植物的耐胁迫能力[6]。同时,也有研究证实青杨雄株的耐胁迫能力(比如抗病耐干旱,抗UV辐射等)显著高于雌株[17, 20-21, 44],雄株叶片的Sphingomonas可能也贡献了其耐胁迫能力的提升。Amnibacterium能产生多种生物活性代谢物,具有抗菌活性,有利于抑制植物病原菌的生长,促进植物发育[45]。雌株的高病原菌感染率可能定向地富集了Amnibacterium[19],以此来抵御病原菌的感染。

青杨雌雄叶际真菌在纲水平和属水平都有显著差异的纲和属。Agaricomycetes在雄株中的相对丰度显著高于雌株,Elmerina属于Agaricomycetes。有研究表明Agaricomycetes有抗氧化作用[46],雄株叶片上更高丰度的Agaricomycetes可能与雄株具有更强的抗氧化作用有关,这也符合Zhang等[19]对青杨叶片的抗氧化研究结果。Ascomycota是叶际真菌最主要的菌群占90%,与其他很多研究报道结果一致[28, 47]。Ascomycota的Aureobasidium、Endoconidioma和Monilinia在雌株叶片上的相对丰度都显著高于雄株,大多数Ascomycota的真菌可以产生次生代谢物,保护宿主免受病原体的侵害[48-49]。如Aureobasidium为叶际常见的真菌属,是一种潜在的植物病原体生物控制剂,对其他微生物有很强的拮抗作用[5]。在腐烂的苹果中分离到大量的Aureobasidium pullulans,研究发现此菌株能够诱发植物的生物防御能力,如抵抗灰霉病和青霉菌等致病菌,进而提高植物的抗病性[50]。雌株独有的真菌Pringsheimia与Aureobasidium的功能相似[51],其可能也会增强雌株的抗病能力。已有研究表明青杨雄株在防御和抑制病原体生长方面,拥有更有效的保护机制,雌株更易感染致病菌[18, 44]。因此,较高的Aureobasidium相对丰度对促进雌株的生长可能具有更大的意义。Endoconidioma能够适应极端波动的紫外线辐射、温度和湿度,生长在暴露的栖息地(叶片,石头等)[52]。植物的挥发性化合物会抑制Monilinia的生长[53],已有研究表明雄株的挥发性化合物显著高于雌株[54],那么显然Monilinia在雄株叶片上的丰度会更低。常见的致病菌Rhodotorula和Exobasidium感染植物后,研究发现会诱发和抗病菌相关的酶活性的提高,如多酚氧化酶、过氧化物酶等[55]。它们在雌株的相对丰度显著高于雄株,这可能与雌株更易感病相关。此外,伞菌纲真菌有降解木质素的功能,能够分解凋落叶[56]。Voriskova在研究分解凋落叶的真菌时发现Aureobasidium在活叶和凋落叶中都大量存在[57-58],Pringsheimia也有降解木质素的功能[59]。这些菌在青杨雌雄叶片上的相对丰度存在着显著差异,这些差异是否会引起雌雄凋落叶分解的差异,这也是一个值得我们进一步去探究的问题。

青杨叶际真菌群落结构的变化与叶片的含水量有显著性关联(P < 0.05),而细菌群落结构与叶片理化性质则无显著相关性(P > 0.05)。水分丰度是影响叶际微生物在叶片表面生长和存活的一个重要因素[60]。叶片含水量增加了叶片表面的润湿性,使微生物更容易利用水,同时叶片湿润度高有利于增加叶片内部营养物质的溶解和扩散,从而给附着微生物提供更多的养分,增加了附生微生物的附着有效性[25, 61]。Yadav等[26]研究也表明,叶片含水量是地中海乔灌木叶际微生物丰度的主要驱动因素。Linaldeddu等对橡树叶际真菌研究表明叶片水分胁迫下会导致叶际真菌菌群的多样性降低[62]。而叶片含水量对于青杨的叶际细菌群落结构没有影响,我们推测可能与采样季节有关,有研究表明季节是影响真菌群落组成结构的主要驱动力[47, 63]。本实验的叶片于9月份采集,秋季叶片已经完全成熟即将变黄,前期研究表明叶际真菌在叶片衰老后的初始分解中扮演主要角色[58]。这个时间叶片有大量的脱落酸产生,而且叶际附生真菌作为活叶植物分泌物的分解者[64],新陈代谢旺盛,活性更高,可能导致真菌对水分更为敏感。如在叶片含水量较高时,能促进真菌Zymoseptoria的孢子生长和萌发[47]。因此,不同季节环境下,影响青杨叶际微生物的主导环境因子仍需进一步探究。

| [1] | Lindow SE, Leveau JHJ. Phyllosphere microbiology. Current Opinion in Biotechnology, 2002, 13(3): 238-243. DOI:10.1016/S0958-1669(02)00313-0 |

| [2] | Lindow SE, Brandl MT. Microbiology of the phyllosphere. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 2003, 69(4): 1875-1883. DOI:10.1128/AEM.69.4.1875-1883.2003 |

| [3] | Vorholt JA. Microbial life in the phyllosphere. Nature Reviews Microbiology, 2012, 10(12): 828-840. DOI:10.1038/nrmicro2910 |

| [4] | Penuelas J, Terradas J. The foliar microbiome. Trends in Plant Science, 2014, 19(5): 278-280. DOI:10.1016/j.tplants.2013.12.007 |

| [5] | Vacher C, Hampe A, Porté AJ, Sauer U, Compant S, Morris CE. The phyllosphere: microbial jungle at the plant-climate interface. Annual Review of Ecology, Evolution, and Systematics, 2016, 47: 1-24. DOI:10.1146/annurev-ecolsys-121415-032238 |

| [6] | Delmotte N, Knief C, Chaffron S, Innerebner G, Roschitzki B, Schlapbach R, von Mering C, Vorholt JA. Community proteogenomics reveals insights into the physiology of phyllosphere bacteria. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 2009, 106(38): 16428-16433. DOI:10.1073/pnas.0905240106 |

| [7] | Murty MG. Nitrogen fixation (acetylene reduction) in the phyllosphere of some economically important plants. Plant and Soil, 1983, 73(1): 151-153. DOI:10.1007/BF02197764 |

| [8] | Fürnkranz M, Wanek W, Richter A, Abell G, Rasche F, Sessitsch A. Nitrogen fixation by phyllosphere bacteria associated with higher plants and their colonizing epiphytes of a tropical lowland rainforest of Costa Rica. The ISME Journal, 2008, 2(5): 561-570. DOI:10.1038/ismej.2008.14 |

| [9] | Rastogi G, Coaker GL, Leveau JHJ. New insights into the structure and function of phyllosphere microbiota through high-throughput molecular approaches. FEMS Microbiology Letters, 2013, 348(1): 1-10. DOI:10.1111/1574-6968.12225 |

| [10] | Bulgarelli D, Schlaeppi K, Spaepen S, Ver Loren van Themaat E, Schulze-Lefert P. Structure and functions of the bacterial microbiota of plants. Annual Review of Plant Biology, 2013, 64: 807-838. DOI:10.1146/annurev-arplant-050312-120106 |

| [11] | Yutthammo C, Thongthammachat N, Pinphanichakarn P, Luepromchai E. Diversity and activity of PAH-degrading bacteria in the phyllosphere of ornamental plants. Microbial Ecolology, 2010, 59(2): 357-368. DOI:10.1007/s00248-009-9631-8 |

| [12] | Kinkel LL. Microbial population dynamics on leaves. Annual Review of Phytopathology, 1997, 35: 327-347. DOI:10.1146/annurev.phyto.35.1.327 |

| [13] | Yang CH, Crowley DE, Borneman J, Keen NT. Microbial phyllosphere populations are more complex than previously realized. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 2001, 98(7): 3889-3894. DOI:10.1073/pnas.051633898 |

| [14] | Renner SS, Ricklefs RE. Dioecy and its correlates in the flowering plants. American Journal of Botany, 1995, 82(5): 596-606. DOI:10.1002/j.1537-2197.1995.tb11504.x |

| [15] | Chen LH, Dong TF, Duan BL. Sex-specific carbon and nitrogen partitioning under N deposition in Populus cathayana. Trees, 2014, 28(3): 793-806. DOI:10.1007/s00468-014-0992-3 |

| [16] |

Liu X. Study on character of Populus cothayna male tree and its genetic dominance. Science and Technology of Qinghai Agriculture and Forestry, 2003(3): 22-23.

(in Chinese) 刘霞. 青杨雄株的形质特征及其优势研究. 青海农林科技, 2003(3): 22-23. DOI:10.3969/j.issn.1004-9967.2003.03.010 |

| [17] | Zhang S, Chen FG, Peng SM, Ma WJ, Korpelainen H, Li CY. Comparative physiological, ultrastructural and proteomic analyses reveal sexual differences in the responses of Populus cathayana under drought stress. Proteomics, 2010, 10(14): 2661-2677. DOI:10.1002/pmic.200900650 |

| [18] | Zhang S, Jiang H, Peng SM, Korpelainen H, Li CY. Sex-related differences in morphological, physiological, and ultrastructural responses of Populus cathayana to chilling. Journal of Experimental Botany, 2011, 62(2): 675-686. DOI:10.1093/jxb/erq306 |

| [19] | Zhang S, Lu S, Xu X, Korpelainen H, Li CY. Changes in antioxidant enzyme activities and isozyme profiles in leaves of male and female Populus cathayana infected with Melampsora larici-populina. Tree Physiology, 2010, 30(1): 116-128. DOI:10.1093/treephys/tpp094 |

| [20] | Xu X, Peng GQ, Wu CC, Korpelainen H, Li CY. Drought inhibits photosynthetic capacity more in females than in males of Populus cathayana. Tree Physiology, 2008, 28(11): 1751-1759. DOI:10.1093/treephys/28.11.1751 |

| [21] | Chen LH, Zhang S, Zhao HX, Korpelainen H, Li CY. Sex-related adaptive responses to interaction of drought and salinity in Populus yunnanensis. Plant, Cell & Environment, 2010, 33(10): 1767-1778. |

| [22] | Xu X, Li YX, Wang BX, Hu JY, Liao YM. Salt stress induced sex-related spatial heterogeneity of gas exchange rates over the leaf surface in Populus cathayana Rehd. Acta Physiologiae Plantarum, 2015, 37: 1709. DOI:10.1007/s11738-014-1709-3 |

| [23] |

Wang BX, Liao YM, Huang YY, Jiang XM, Xu X. Sex-specific heterogeneity in stomatal distribution and gas exchange of male and female Populus cathayana leaves. Acta Botanica Yunnanica, 2009, 31(5): 439-446.

(in Chinese) 王碧霞, 廖咏梅, 黄尤优, 蒋雪梅, 胥晓. 青杨雌雄叶片气孔分布及气体交换的异质性差异. 云南植物研究, 2009, 31(5): 439-446. |

| [24] | Xu X, Zhao HX, Zhang XL, Hänninen H, Korpelainen H, Li CY, Tognetti R. Different growth sensitivity to enhanced UV-B radiation between male and female Populus cathayana. Tree Physiology, 2010, 30(12): 1489-1498. DOI:10.1093/treephys/tpq094 |

| [25] | Whipps JM, Hand P, Pink D, Bending GD. Phyllosphere microbiology with special reference to diversity and plant genotype. Journal of Applied Microbiology, 2008, 105(6): 1744-1755. DOI:10.1111/j.1365-2672.2008.03906.x |

| [26] | Yadav RKP, Karamanoli K, Vokou D. Bacterial colonization of the phyllosphere of mediterranean perennial species as influenced by leaf structural and chemical features. Microbial Ecology, 2005, 50(2): 185-196. DOI:10.1007/s00248-004-0171-y |

| [27] | Kembel SW, O'Connor TK, Arnold HK, Hubbell SP, Wright SJ, Green JL. Relationships between phyllosphere bacterial communities and plant functional traits in a neotropical forest. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 2014, 111(38): 13715-13720. DOI:10.1073/pnas.1216057111 |

| [28] | Kembel SW, Mueller RC. Plant traits and taxonomy drive host associations in tropical phyllosphere fungal communities. Botany, 2014, 92(4): 303-311. DOI:10.1139/cjb-2013-0194 |

| [29] | Ren GD, Zhu CW, Alam MS, Tokida T, Sakai H, Nakamura H, Usui Y, Zhu JG, Hasegawa T, Jia ZJ. Response of soil, leaf endosphere and phyllosphere bacterial communities to elevated CO2 and soil temperature in a rice paddy. Plant and Soil, 2015, 392(1/2): 27-44. |

| [30] |

Sun H, Li H, Zhan YG, Li Y. Phyllosphere bacterial community structure of Osmanthus fragrans and Nerium indicium in different habitats. Chinese Journal of Applied Ecology, 2018, 29(5): 1653-1659.

(in Chinese) 孙泓, 李慧, 詹亚光, 李杨. 不同生境中桂花和夹竹桃叶际细菌的群落结构. 应用生态学报, 2018, 29(5): 1653-1659. |

| [31] | Ding JL, Jiang X, Guan DW, Zhao BS, Ma MC, Zhou BK, Cao FM, Yang XH, Li L, Li J. Influence of inorganic fertilizer and organic manure application on fungal communities in a long-term field experiment of Chinese Mollisols. Applied Soil Ecology, 2017, 111: 114-122. DOI:10.1016/j.apsoil.2016.12.003 |

| [32] | Kuczynski J, Stombaugh J, Walters WA, González A, Caporaso JG, Knight R. Using QⅡME to analyze 16S rRNA gene sequences from microbial communities. Current Protocols Bioinformatics, 2011, 36(1): 10.7.1-10.7.20. |

| [33] | White JR, Nagarajan N, Pop M. Statistical methods for detecting differentially abundant features in clinical metagenomic samples. PLoS Computational Biology, 2009, 5(4): e1000352. DOI:10.1371/journal.pcbi.1000352 |

| [34] | Bodenhausen N, Bortfeld-Miller M, Ackermann M, Vorholt JA. A synthetic community approach reveals plant genotypes affecting the phyllosphere microbiota. PLoS Genetics, 2014, 10(4): e1004283. DOI:10.1371/journal.pgen.1004283 |

| [35] | Smets W, Wuyts K, Oerlemans E, Wuyts S, Denys S, Samson R, Lebeer S. Impact of urban land use on the bacterial phyllosphere of ivy (Hedera sp.). Atmospheric Environment, 2016, 147: 376-383. DOI:10.1016/j.atmosenv.2016.10.017 |

| [36] | Redford AJ, Bowers RM, Knight R, Linhart Y, Fierer N. The ecology of the phyllosphere: geographic and phylogenetic variability in the distribution of bacteria on tree leaves. Environmental Microbiology, 2010, 12(11): 2885-2893. DOI:10.1111/j.1462-2920.2010.02258.x |

| [37] | Redford AJ, Fierer N. Bacterial succession on the leaf surface: a novel system for studying successional dynamics. Microbial Ecology, 2009, 58(1): 189-198. DOI:10.1007/s00248-009-9495-y |

| [38] | Kim M, Singh D, Lai-Hoe A, Go R, Abdul RR, Ainuddin AN, Chun J, Adams JM. Distinctive phyllosphere bacterial communities in tropical trees. Microbial Ecology, 2012, 63(3): 674-681. DOI:10.1007/s00248-011-9953-1 |

| [39] | Hunter PJ, Hand P, Pink D, Whipps JM, Bending GD. Both leaf properties and microbe-microbe interactions influence within-species variation in bacterial population diversity and structure in the lettuce (Lactuca Species) phyllosphere. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 2010, 76(24): 8117-8125. DOI:10.1128/AEM.01321-10 |

| [40] | Wu QP, Tang Y, Dong TF, Liao YM, Li DD, He XH, Xu X. Additional AM fungi inoculation increase Populus cathayana intersexual competition. Frontiers in Plant Science, 2018, 9: 607. DOI:10.3389/fpls.2018.00607 |

| [41] | Stone BW, Jackson CR. Biogeographic patterns between bacterial phyllosphere communities of the southern magnolia (Magnolia grandiflora) in a small forest. Microbial Ecology, 2016, 71(4): 954-961. DOI:10.1007/s00248-016-0738-4 |

| [42] | Innerebner G, Knief C, Vorholt JA. Protection of Arabidopsis thaliana against Leaf-Pathogenic Pseudomonas syringae by Sphingomonas strains in a controlled model system. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 2011, 77(10): 3202-3210. DOI:10.1128/AEM.00133-11 |

| [43] | Zhou LS, Li H, Zhang Y, Han SQ, Xu H. Sphingomonas from petroleum-contaminated soils in Shenfu, China and their PAHs degradation abilities. Brazilian Journal of Microbiology, 2016, 47(2): 271-278. DOI:10.1016/j.bjm.2016.01.001 |

| [44] | Zhang S, Chen LH, Duan BL, Korpelainen H, Li CY. Populus cathayana males exhibit more efficient protective mechanisms than females under drought stress. Forest Ecology and Management, 2012, 275: 68-78. DOI:10.1016/j.foreco.2012.03.014 |

| [45] | Jiang ZK, Tuo L, Huang DL, Osterman IA, Tyurin AP, Liu SW, Lukyanov DA, Sergiev PV, Dontsova OA, Korshun VA, Li FN, Sun CH. Diversity, novelty, and antimicrobial activity of endophytic Actinobacteria from mangrove plants in beilun estuary national nature reserve of Guangxi, China. Frontiers in Microbiology, 2018, 9: 868. DOI:10.3389/fmicb.2018.00868 |

| [46] | Cilerdzic J, Kosanic M, Stajić M, Vukojevic J, Ranković B. Species of genus ganoderma (Agaricomycetes) fermentation broth: a novel antioxidant and antimicrobial agent. International Journal of Medicinal Mushrooms, 2016, 18(5): 397-404. DOI:10.1615/IntJMedMushrooms.v18.i5.30 |

| [47] | Jumpponen A, Jones KL. Seasonally dynamic fungal communities in the Quercus macrocarpa phyllosphere differ between urban and nonurban environments. New Phytologist, 2010, 186(2): 496-513. DOI:10.1111/j.1469-8137.2010.03197.x |

| [48] | Rodriguez RJ, White JF Jr, Arnold AE, Redman RS. Fungal endophytes: diversity and functional roles. New Phytologist, 2009, 182(2): 314-330. DOI:10.1111/j.1469-8137.2009.02773.x |

| [49] | Schulz B, Römmert AK, Dammann U, Aust HJ, Strack D. The endophyte-host interaction: a balanced antagonism?. Mycological Research, 1999, 103(10): 1275-1283. DOI:10.1017/S0953756299008540 |

| [50] | Ippolito A, El Ghaouth A, Wilson CL, Wisniewski M. Control of postharvest decay of apple fruit by Aureobasidium pullulans and induction of defense responses. Postharvest Biology and Technology, 2000, 19(3): 265-272. DOI:10.1016/S0925-5214(00)00104-6 |

| [51] | de Hoog GS, Yurlova NA. Conidiogenesis, nutritional physiology and taxonomy of Aureobasidium and Hormonema. Antonie van Leeuwenhoek, 1994, 65(1): 41-54. DOI:10.1007/BF00878278 |

| [52] | Mirzaei S, Moghadam NJ, Khaledi E, Abdollahzadeh J, Amini J, Abrinbana M. Molecular and morphological characterization of Endoconidioma populi from Kurdistan province, Iran. Mycologia Iranica, 2015, 2(2): 127-133. |

| [53] | Neri F, Mari M, Brigati S, Bertolini P. Fungicidal activity of plant volatile compounds for controlling Monilinia laxa in stone fruit. Plant Disease, 2007, 91(1): 30-35. DOI:10.1094/PD-91-0030 |

| [54] | Cornelissen T, Stiling P. Sex-biased herbivory: a meta-analysis of the effects of gender on plant-herbivore interactions. Oikos, 2005, 111(3): 488-500. DOI:10.1111/j.1600-0706.2005.14075.x |

| [55] | Chakraborty BN, Dutta S, Chakraborty U. Biochemical responses of tea plants induced by foliar infection with Exobasidium vexans. Indian Phytopath, 2002, 55(1): 8-13. |

| [56] | Morgenstern I, Klopman S, Hibbett DS. Molecular evolution and diversity of lignin degrading heme peroxidases in the Agaricomycetes. Journal of Molecular Evolution, 2008, 66(3): 243-257. DOI:10.1007/s00239-008-9079-3 |

| [57] | Osono T. Role of phyllosphere fungi of forest trees in the development of decomposer fungal communities and decomposition processes of leaf litter. Canadian Journal of Microbiology, 2006, 52(8): 701-716. DOI:10.1139/w06-023 |

| [58] | Voříšková J, Baldrian P. Fungal community on decomposing leaf litter undergoes rapid successional changes. The ISME Journal, 2013, 7(3): 477-486. DOI:10.1038/ismej.2012.116 |

| [59] | Fillat Ú, Martín-Sampedro R, Macaya-Sanz D, Martín JA, Eugenio María EE. Potential of lignin-degrading endophytic fungi on lignocellulosic biorefineries//Maheshwari D, Annapurna K. Endophytes: Crop Productivity and Protection. Cham: Springer, 2017. |

| [60] | Beattie GA. Water relations in the interaction of foliar bacterial pathogens with plants. Annual Review of Phytopathology, 2011, 49: 533-555. DOI:10.1146/annurev-phyto-073009-114436 |

| [61] | Bunster L, Fokkema NJ, Schippers B. Effect of surface-active Pseudomonas spp. on leaf wettability. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 1989, 55(6): 1340-1345. DOI:10.1128/AEM.55.6.1340-1345.1989 |

| [62] | Linaldeddu BT, Sirca C, Spano D, Franceschini A. Variation of endophytic cork oak-associated fungal communities in relation to plant health and water stress. Forest Pathology, 2011, 41(3): 193-201. DOI:10.1111/j.1439-0329.2010.00652.x |

| [63] | Gomes T, Pereira JA, Benhadi J, Lino-Neto T, Baptista P. Endophytic and epiphytic phyllosphere fungal communities are shaped by different environmental factors in a mediterranean ecosystem. Microbial Ecology, 2018, 76(3): 668-679. DOI:10.1007/s00248-018-1161-9 |

| [64] | Jumpponen A, Jones KL. Massively parallel 454 sequencing indicates hyperdiverse fungal communities in temperate Quercus macrocarpa phyllosphere. New Phytologist, 2009, 184(2): 438-448. DOI:10.1111/j.1469-8137.2009.02990.x |

2020, Vol. 60

2020, Vol. 60