中国科学院微生物研究所,中国微生物学会,中国菌物学会

文章信息

- 甄莉, 吴耿, 杨渐, 蒋宏忱. 2019

- Li Zhen, Geng Wu, Jian Yang, Hongchen Jiang. 2019

- 西藏热泉沉积物的硫氧化细菌多样性及其影响因素

- Distribution and diversity of sulfur-oxidizing bacteria in the surface sediments of Tibetan hot springs

- 微生物学报, 59(6): 1089-1104

- Acta Microbiologica Sinica, 59(6): 1089-1104

-

文章历史

- 收稿日期:2019-03-13

- 修回日期:2019-04-26

- 网络出版日期:2019-05-10

硫元素是自然环境中最重要的元素之一,是氨基酸和酶的关键组成成分[1]。自然界中的硫元素具有多种形态(如单质硫、无机和有机硫化合物),它们之间通过各种生物、物理、化学过程参与自然界生态循环[2]。硫循环过程包括硫氧化、硫还原、硫酸盐还原等过程,同时关联着碳、氮等元素的地球化学循环,是地球重要的元素循环过程之一[3-4]。其中微生物在推动全球硫循环中扮演着重要角色[5]。硫氧化是硫循环的重要组成部分,通常指单质硫或还原性硫化物被微生物氧化的过程,常由硫氧化细菌(sulfur-oxidizing bacteria,SOB)催化。SOB的硫氧化过程是由一系列的酶催化完成,其中soxB基因编码的硫代硫酸盐水解酶就是最为关键的酶之一[6-9]。因此,soxB常被用作标记基因广泛应用于研究各种自然环境中的SOB多样性[10],例如热泉[11]、盐碱湖[12]、深海热液[13]等。

热泉是典型的陆地热、酸极端环境,有着活跃的生物地球化学循环(如硫循环)过程[14]。同时,热泉环境(如高温、低氧)与原始地球形成初期的环境极其相近[15],因此,研究热泉微生物生态及其参与的元素循环过程,对于我们探究地球早期生命具有重要的指示作用。另外,热泉环境存在着多种形态的硫化物,可为SOB生长和新陈代谢提供能量[14]。前人基于16S rRNA基因研究发现热泉存在大量硫氧化细菌群落,比如硫杆菌属、硫微螺菌属和硫化叶菌属等[16-17]。以上研究主要采用16S rRNA基因分析了热泉总细菌或古菌群落多样性,对于全面认识热泉硫氧化微生物群落多样性仍存在不足。功能基因分析在探测某一特殊功能微生物群落(如SOB)多样性方面具有较强优势[12]。因此,借助功能基因(如soxB基因)分析方法将有助于我们进一步加深认识热泉SOB群落多样性及其响应环境因子的变化。

我国西藏地区具有丰富的地热资源(如热泉)[18]。该地区热泉分布广泛,受人类活动干扰较少,且具有多种环境梯度[19],如本研究中西藏热泉温度梯度(28.6–90 ℃)和pH梯度(pH 3.0–9.1)。因此,西藏地区热泉是研究嗜热和赖热微生物多样性及其响应环境因子变化的天然实验场。前人在西藏地区已开展大量微生物多样性研究[20-22],但对于硫氧化菌群多样性仍未得到全面认识。因此,本研究以西藏热泉为研究对象,通过克隆文库技术分析soxB基因的多样性,揭示硫氧化细菌的多样性和群落组成,并初步研究其对各种环境因子的相关性。相关研究结果可加深我们对热泉生境中硫氧化细菌群落生态多样性的认知,为理解热泉生境硫循环生物地球化学过程提供数据基础。

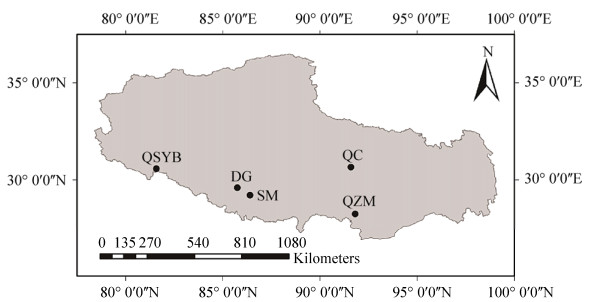

1 材料和方法 1.1 采样点分布本研究共选取25个采样点,涉及区域分布在西藏5个地区:曲色涌巴(标记为QSYB)有4个样点;打加(标记为DG)有14个样点;色米(标记为SM)有1个样点;曲才(标记为QC)有3个样点;曲卓木(QZM)有3个样点。采样点的地理位置如图 1所示。

|

| 图 1 中国西藏热泉研究区域分布图 Figure 1 Regional map of research on Tibet hot springs in China |

1.2 样品采集及水体理化参数测试

现场测量西藏各个热泉采样点的GPS位置、海拔、pH、温度等理化参数。每个采样点的GPS及海拔高度信息由便携式仪器(eTrex H,Garmin,USA)检测。温度和pH由便携式温度计和pH计(LaMotte,MD,USA)检测。电导率和总溶解固体含量使用电导率测定仪(SX713,上海三信仪表)。热泉水总二价铁Fe(Ⅱ)和硫化物含量测试采用哈希试剂盒(HACH,USA)。

采集热泉水,用0.7 μm玻璃纤维滤膜(Whatman GF/F filters)过滤后,分装在30 mL的棕色玻璃瓶中(所用玻璃纤维滤膜和棕色玻璃瓶已经450 ℃马弗炉高温灼烧,消除有机物),标记后用封口膜包装,以防止标签掉落和样品泄漏,样品全程置于干冰中运输。运回实验室后存放于4 ℃冰箱,用于后续溶解性有机碳(DOC)的测定。另外,在水与沉积物接触处约1 cm位置采集沉积物,分装于无菌的50 mL离心管,标记后用封口膜包装,以防止标签掉落和样品泄漏,样品全程置于干冰中运输。运回实验室后放于–80 ℃超低温冰箱储存,用于后续热泉沉积物DNA提取和总有机碳(TOC)的测定。

用N/C2100S分析仪(Analytik Jena,Germany)测量热泉水样中的溶解性有机碳(DOC)和沉积物样品中的总有机碳(TOC)浓度。用于检测TOC的热泉沉积物样品需要先用HCl酸化去除沉积物中的碳酸盐,用去离子水反复冲洗去除Cl–后,将pH调至中性,放置于65 ℃烘箱烘至干燥,用研钵研至粉末状态待用。所有样品避免反复冻融。

1.3 DNA提取和PCR扩增采用试剂盒Fast DNA Soil-Direct Kit (MP BIO,美国)提取西藏热泉沉积物样品总DNA。以提取的总DNA作为模板,参照前人文献中的PCR条件[23],用引物soxB693F (5'-ATCGGNCARGCN TTYCCNTA-3')/soxB1446B(5'-CATGTCNCCNCCRTGYTG-3')对soxB基因进行PCR扩增[24]。使用1%的琼脂糖凝胶电泳检测PCR产物,同时选用DL2000 DNA作为Marker,在紫外灯下观察,在该Marker对应的750 bp的位置切取含目标条带的琼脂糖凝胶。用试剂盒Axy Prep DNA Gel Extraction Kit (Axygen,美国)纯化PCR产物,回收DNA。

1.4 克隆文库构建和系统发育分析参照前人文献中的方法[25],将纯化回收的PCR产物连接到pGEM-T载体上(Promega,美国),并转化到大肠杆菌DH5α感受态细胞中,将转化后的细胞均匀涂布到含有氨苄青霉素钠盐(100 μg/mL)、5-溴-4-氯-3-吲哚-β-D-半乳糖苷(简称X-Gal,80 μg/mL)以及异丙基-β-D-硫代半乳糖苷,(简称IPTG,0.5 mmol/L)的LB抗性筛选平板上,置于37 ℃培养箱培养过夜。对每1个采样点都建立1个克隆文库,总共构建了25个soxB基因克隆文库,编号与样点名称相同:QC02、QC04、QC05、SM01、DG02、DG07、DG12、QSYB08、QSYB09-2、QSYB09-3、QSYB10、DG01-1、DG01-2、DG01-3、DG01-4、DG01-5、DG01-6、DG02-1、DG02-2、DG02-3、DG02-4、DG02-5、QZM02、QZM04和QZM06。对于每个克隆文库,进行蓝白斑筛选,随机挑取50个左右的阳性克隆子,然后进行限制性片段长度多态性(restriction fragment length polymorphism,简称RLFP)分析[26]。根据每一种酶切带型,挑选出一个代表性克隆子送至上海生工(武汉)测序部测序。返回的原始序列使用Bioedit软件进行修剪,然后在线使用National Center for Biotechnology Information网站(简称为NCBI,http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov.)对修剪后的序列进行比对(BLASTX),选取有效的soxB基因序列。以98%序列相似性作为分类标准,使用Mothur软件对soxB基因克隆序列进行分类操作单元(即operational taxonomic unit,简称OTU)划分[27]。从每个OTU中选取一条序列作为代表序列,将其与NCBI数据库中的同源氨基酸序列进行比对,将相似性最高的已知同源氨基酸序列选取为参考序列,使用BioEdit软件将参考序列和代表氨基酸序列对齐、修剪后,导入MEGA 7.0软件构建系统发育树。该研究中测定的克隆序列已经递交至GenBank中,获得登录号为MK441756–MK441836。

1.5 统计分析根据前人研究方法[23],soxB基因克隆文库的覆盖度使用公式C = 1–n/N计算(其中C为覆盖度,n为文库中只出现一次的克隆数量,N为该文库克隆总数)。使用PAST(http://folk.uio.no/ohammer/past/)进行聚类分析、Mantel检验、克隆文库多样性指数分析硫氧化细菌群落组成及其与环境变量的相关关系。另外,使用SPSS 22.0分析环境变量的相关性。

2 结果和分析 2.1 水体理化性质西藏热泉样品的温度为28.6–90 ℃,pH为3.0–9.1。其他主要理化参数如表 1所示。在5个采样地区中,除色米(SM)地区仅有1个样点外,其余4个采样地区曲色涌巴(QSYB)、打加(DG)、曲才(QC)、曲卓木(QZM)的热泉样点在区内都各自形成了一定的pH和温度范围。另外,仅DG02为酸性热泉,QC02、QC04、QC05、DG07、DG12、SM01、QZM02、QZM04这8个热泉水体pH在7左右,其余16个样点热泉水体偏碱性(表 1)。另外,Spearman相关性分析显示,电导率与总溶解固体(TDS)、pH、温度存在显著相关性(P < 0.05);pH与溶解有机碳(DOC)和TDS以及温度与TDS也存在显著相关性。

| Sample ID | GPS location/(E/N) | Altitude/m | T/℃ | pH | EC/(μs/cm) | TDS/(mg/L) | TOC/% | DOC/(mg/L) | Fe(Ⅱ)/(mg/L) | Sulfide/(mg/L) |

| QC02 | 91°35'28.46"/ 30°39'58.90" | 4497.0 | 28.6 | 7.5 | n.a. | n.a. | 0.1 | n.a. | n.a. | 0.0 |

| QC04 | 91°35'28.10"/ 30°40'0.52" | 4500.0 | 69.5 | 6.8 | 2170.0 | 1064.0 | 4.8 | 1.9 | 0.00 | 0.02 |

| QC05 | 91°35'44.27"/ 30°38'53.56" | 4495.0 | 40.8 | 7.0 | 1888.0 | 925.7 | 0.7 | 2.8 | 0.00 | 0.02 |

| DG02 | 85°44'52.33"/ 29°36'11.23" | 5084.0 | 36.7 | 3.0 | 439.8 | 216.0 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 0.56 | 0.00 |

| DG07 | 85°44'48.44"/ 29°36'13.64" | 5073.0 | 82.1 | 7.0 | 1872.0 | 909.0 | n.a. | n.a. | 0.02 | 0.11 |

| DG12 | 85°44'52.22"/ 29°36'28.83" | 5077.0 | 77.8 | 7.0 | 1805.0 | 884.8 | 0.3 | 0.1 | 0.01 | 0.15 |

| SM01 | 86°24'17.06"/ 29°12'55.62" | 4263.0 | 85.9 | 7.2 | 2307.0 | 1109.0 | 0.1 | n.a. | 0.82 | 0.06 |

| QSYB08 | 81°34'50.66"/ 30°35'4.92" | 4620.0 | 84.0 | 8.3 | 2077.0 | 998.4 | 0.0 | 15.6 | 0.04 | 0.06 |

| QSYB09-2 | 81°34'49.98"/ 30°35'5.17" | 4620.0 | 70.0 | 8.9 | 1848.0 | 906.1 | 0.0 | 21.3 | 0.00 | 0.35 |

| QSYB09-3 | 81°34'49.98"/ 30°35'5.17" | 4620.0 | 70.0 | 8.9 | 1828.0 | 896.3 | 0.1 | 28.4 | 0.03 | 0.43 |

| QSYB10 | 81°34'49.65"/ 30°35'4.45" | 4622.0 | 90.0 | 9.1 | 1845.0 | 904.7 | 0.0 | 10.3 | 0.02 | 0.22 |

| DG01-1 | 85°45'03.37"/ 29°35'53.80" | 5057.0 | 77.0 | 8.2 | 1951.0 | 956.6 | 0.0 | 18.4 | 0.03 | 0.07 |

| DG01-2 | 85°45'3.37"/ 29°35'53.80" | 5057.0 | 71.0 | 8.6 | 1837.0 | 900.7 | 0.1 | 29.0 | 0.02 | 0.10 |

| DG01-3 | 85°45'3.37"/ 29°35'53.80" | 5057.0 | 60.0 | 8.7 | 1834.0 | 899.3 | 1.0 | 21.9 | 0.03 | 0.19 |

| DG01-4 | 85°45'3.37"/ 29°35'53.80" | 5057.0 | 55.2 | 8.7 | 1855.0 | 909.6 | 0.7 | 8.1 | 0.16 | 0.03 |

| DG01-5 | 85°45'3.37"/ 29°35'53.80" | 5057.0 | 50.0 | 8.8 | 1840.0 | 902.3 | 8.3 | 18.8 | 0.07 | 0.03 |

| DG01-6 | 85°45'3.37"/ 29°35'53.80" | 5057.0 | 46.0 | 8.6 | 1835.0 | 899.8 | 2.9 | 23.5 | 0.00 | 0.05 |

| DG02-1 | 85°45'2.45"/ 29°35'55.74" | 5058.0 | 70.0 | 8.6 | 1864.0 | 914.0 | 0.2 | 4.7 | 0.05 | 0.03 |

| DG02-2 | 85°45'2.45"/ 29°35'55.74" | 5058.0 | 63.0 | 8.6 | 1842.0 | 903.1 | 15.6 | 8.0 | 0.12 | 0.02 |

| DG02-3 | 85°45'2.45"/ 29°35'55.74" | 5058.0 | 57.0 | 8.6 | 1856.0 | 909.8 | 1.0 | 6.3 | 0.01 | 0.02 |

| DG02-4 | 85°45'2.45"/ 29°35'55.74" | 5058.0 | 48.5 | 8.7 | 1847.0 | 905.5 | 2.6 | 5.8 | 0.00 | 0.03 |

| DG02-5 | 85°45'2.45"/ 29°35'55.74" | 5058.0 | 43.0 | 8.7 | 1851.0 | 907.6 | 2.0 | 13.0 | 0.00 | 0.03 |

| QZM02 | 91°48'39.12"/ 28°14'36.53" | 4519.0 | 65.0 | 6.5 | 1670.0 | 819.0 | 0.4 | 21.2 | 1.56 | 0.02 |

| QZM04 | 91°48'45.88"/ 28°14'11.94" | 4853.0 | 72.0 | 6.9 | 2037.0 | 998.4 | 4.7 | 18.3 | 0.88 | 0.02 |

| QZM06 | 91°48'26.10"/ 28°13'45.80" | 4743.0 | 71.0 | 8.3 | 1071.0 | 996.5 | 3.0 | 18.4 | 1.09 | 0.02 |

| n.a. is not detected. | ||||||||||

2.2 soxB基因克隆文库分析

本研究共筛选出644个有效soxB基因克隆子,25个热泉样点的所有检出的soxB基因克隆序列可划分为83个OTU。其中,QC05热泉样点具有10个OTU,QZM4热泉样点具有8个OTU,DG01_2和QSYB08热泉样点各有7个OTU,DG07、QSYB09_2和QSYB10热泉样点各有6个OTU,SM01热泉样点具有5个OTU,DG01_1、DG01_5、QSYB09_3和QZM02热泉样点各有4个OTU,DG01_3和DG12热泉样点各有2个OTU。DG01_4、DG02_4和QC04热泉样点各有1个OTU。所得25个克隆文库的覆盖度范围为87%–100%。多样性指数(Chao_1、Shannon_H、Simpson_1-D)分析结果如表 2所示。

| Clone libraries | Library size (No. of clones) | Observed OTUs | Coverage/% | Chao_1 | Shannon_H | Simpson_1-D | Equitability |

| DG01_1 | 22 | 4 | 100 | 4.0 | 1.4 | 0.7 | 1.0 |

| DG01_2 | 37 | 7 | 100 | 7.0 | 1.8 | 0.8 | 0.9 |

| DG01_3 | 17 | 2 | 100 | 2.0 | 0.6 | 0.4 | 0.9 |

| DG01_4 | 13 | 1 | 100 | 1.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| DG01_5 | 38 | 4 | 97 | 5.0 | 1.3 | 0.7 | 0.8 |

| DG01_6 | 22 | 3 | 100 | 4.0 | 1.3 | 0.7 | 0.9 |

| DG02_1 | 15 | 3 | 93 | 3.0 | 0.8 | 0.5 | 0.7 |

| DG02_2 | 18 | 3 | 88 | 4.0 | 0.4 | 0.2 | 0.4 |

| DG02_3 | 24 | 3 | 100 | 3.0 | 0.9 | 0.5 | 0.8 |

| DG02_4 | 22 | 1 | 100 | 1.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| DG02_5 | 20 | 3 | 90 | 5.0 | 0.9 | 0.5 | 0.7 |

| DG07 | 43 | 6 | 94 | 9.0 | 0.9 | 0.4 | 0.5 |

| DG12 | 19 | 2 | 94 | 2.0 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.3 |

| DG02 | 33 | 3 | 100 | 3.0 | 0.6 | 0.3 | 0.5 |

| QC02 | 9 | 3 | 100 | 3.0 | 1.0 | 0.6 | 0.9 |

| QC04 | 21 | 1 | 100 | 1.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| QC05 | 29 | 10 | 86 | 13.0 | 2.1 | 0.9 | 0.9 |

| QSYB08 | 31 | 7 | 87 | 11.0 | 1.6 | 0.7 | 0.8 |

| QSYB09_2 | 31 | 6 | 93 | 6.5 | 1.5 | 0.7 | 0.8 |

| QSYB09_3 | 38 | 4 | 100 | 4.0 | 1.1 | 0.6 | 0.8 |

| QSYB10 | 39 | 6 | 97 | 7.0 | 1.7 | 0.8 | 0.9 |

| QZM02 | 10 | 4 | 90 | 4.0 | 1.2 | 0.7 | 0.9 |

| QZM04 | 36 | 8 | 97 | 8.3 | 1.7 | 0.8 | 0.8 |

| QZM06 | 14 | 3 | 100 | 3.0 | 1.0 | 0.6 | 0.9 |

| SM01 | 29 | 5 | 96 | 5.0 | 1.0 | 0.5 | 0.6 |

系统发育分析显示西藏热泉沉积物中的硫氧化细菌分属于α-proteobacteria、β-Poteobacteria和γ-Proteobacteria三个纲,属于α-Proteobacteria纲的soxB基因OTU可分为Rhodobacterales、Rhodospirillales和Rhizobiales三个目;属于β-Poteobacteria纲的soxB基因OTU可分为Burkholderiales、Nitrosomonadales、Neisseriales和Rhodocyclales 4个目;属于γ-Proteobacteria纲的soxB基因OTU属于1个目(即Chromatiales) (图 2)。

|

| 图 2 soxB基因编码的氨基酸序列系统发育树 Figure 2 Phylogenetic tree constructed by amino acid sequence translated from the soxB gene sequences in twenty five clone libraries. Maximum likelihood tree showing the phylogenetic relationships of the deduced SoxB protein sequences translated from the soxB gene clone sequences obtained in this study and their closely related sequences from the GenBank database. The numbers following OTU represent different OTUs. In the brackets, there is the number of clones of the OTU/ the number of clones of the clone library. The scale bar indicates the expected number of changes per homologous position. Bootstrap values of (1000 replicates) > 50% are shown. The SoxB amino acid sequence from Aquifex aeolicus was used as outgroup |

在纲级别的水平上,各热泉样点之间的soxB基因OTU组成没有显著地域差异(图 2和3)。在本研究的25个热泉样点中,有15个样点(QSYB10、QSYB09_3、QSYB08、QC05、QZM06、QSYB09_2、DG01_2、G01_1、DG07、QZM04、SM01、G01_4、QC04、DG02和DG12)的硫氧化细菌群落以β-Proteobacteria纲为主(相对丰度 > 53%);而α-Proteobacteria纲在DG01_5、DG02_1、DG01_6、DG02_3、DG02_4、DG01_3和QC02等7个热泉样品硫氧化细菌群落中占优势(相对丰度 > 61%),γ-Proteobacteria纲在DG02_2和DG02_5热泉样品硫氧化细菌群落中占优势(相对丰度 > 93%)。此外,α-Proteobacteria和β-Proteobacteria纲在QZM02热泉样品硫氧化细菌群落中各约占一半(相对丰度 = 50%)。

|

| 图 3 西藏热泉沉积物soxB基因克隆文库聚类分析和群落组成情况 Figure 3 Cluster analysis and community compositions of the soxB gene clone libraries retrieved from the studied Tibetan hot spring sediment samples |

在目(Order)级别的水平上,各热泉样点之间的soxB基因OTU组成具有差异(图 2)。隶属于α-Proteobacteria纲的三个目的soxB基因OTU分布没有体现出明显地域差别:属于Rhodobacterales目的soxB基因OTU存在于QSYB10、QSYB09_3、DG01_1和DG01_2等9个热泉样点。这些soxB基因OTU序列与分离自西藏曲才热泉(温度65.7 ℃,pH7.0)沉积物的Rhodobacter thermarum (WP_128514891)和分离自某河口沉积物的Rhodobacter aestuarii (WP_076483094)等序列相似。R. thermarum与R. aestuarii均是光合紫色非硫细菌,能进行光合异养生长[28-30]。属于Rhodospirillales目的soxB基因OTU存在于QC05、DG01_1、DG01_5、DG02和DG07等5个热泉样点。这些soxB基因OTU序列与分离自亚速尔群岛某热泉的Tepidamorphus gemmatus (WP_114377142)序列相似,T. gemmatus最佳生长温度为45–50 ℃[31]。属于Rhizobiales目的soxB基因OTU存在于DG07、DG01_5、DG02_1、DG01_6、DG02_3、DG02_4、DG01_3和QC02等8个热泉样点。这些soxB基因OTU序列与分离油污染土壤且具有降解复杂有机质的Pseudorhodoplanes sinuspersici (WP_086090114)相似[32]。

在β-Proteobacteria纲中,属于Rhodocyclales目soxB基因OTU仅存在于DG07和SM01共2个热泉样点。这些soxB基因OTU序列与具有硫氧化功能的Azonexus hydrophilus序列相似[33]。属于Burkholderiales目的soxB基因OTU存在于QSYB10、QSYB09_3、QSYB08、QC05、QZM06、QSYB09_2、DG01_2、G01_1、QZM02、QZM04、SM01、QC04和DG02等13个热泉样点。这些soxB基因OTU序列与具有硫代硫酸盐氧化功能(GenBank描述)的Thiomonas spp. (WP_018914579)和Hydrogenophaga spp.(AGJ03162)等序列相似。属于Nitrosomonadales目soxB基因OTU存在于QSYB10、QSYB09_3、QSYB08、QC05、DG07、QZM02、QZM04、SM01、DG02_3、DG01_3、DG01_4和DG12等12个热泉样点。这些soxB基因OTU序列与分离自铀矿且具有氧化硫化合物功能的Sulfuriferula plumbiphila (ABR67374)[34]和Thiobacillus spp.等序列相似。属于Neisseriales目的soxB基因OTU存在于QSYB08、DG01_5、DG02_1、DG01_6和DG02_5等5个热泉样点。这些soxB基因OTU序列与具有硫化物氧化功能的Vitreoscilla filiformis (WP_089416040)序列相似,V. filiformis嗜微氧,通常生长在贫氧环境中,在低营养浓度下生长最好[35]。

γ-Proteobacteria纲中的soxB基因OTU都属于Chromatiales目,仅在QSYB09_3、QSYB08、QC05、QZM02、DG02_2和DG02_5等6个热泉样点特有。这些soxB基因OTU序列与源自日本某热泉(温度50 ℃)且具有硫氧化功能的Sulfurivermis fontis (WP_127477683)等序列相似[36]。

在OTU水平上,西藏各热泉沉积物样品中优势OTU(在某个样品中相对丰度大于 > 20%)差别非常大(表 3)。大部分优势OTU仅存在于唯一1个样点中,不与其他样点共享。另外,OTU03为DG01_6、DG02_3、DG02_4所共有,OTU03为DG01_3、DG01_4、DG02_3、DG02_5所共有,OTU08为QC05、QZM06所共有,OTU09为DG02_2、DG02_5所共有,OTU14为DG01_5、DG02_1所共有,OTU19为QZM02、QZM06所共有。这些优势OTU代表序列的soxB基因氨基酸序列相似性为76%–99%,主要分属于α-、β-和γ-Proteobacteria(表 3)。

| OTU ID | Sample ID (relative abundance) | Taxonomy(Class) | Closest relative | soxB gene identity/% |

| OTU01 | DGJ07(65.1%) | Betaproteobacteria | Azonexus hydrophilus | 93 |

| OTU02 | DGJ12(94.7%) | Betaproteobacteria | Annwoodia aquaesulis | 79 |

| OTU03 | DG01_6(40.9%)/ DG02_3(62.5%)/ DG02_4(100%) | Alphaproteobacteria | Elioraea sp. | 94 |

| OTU04 | DG02(81.8%) | Betaproteobacteria | Thiomonas sp. | 91 |

| OTU05 | DG01_3(29.4%) DG01_4(100%)/ DG02_3(29.2%)/ DG02_5(25.0%) | Betaproteobacteria | Thiobacillaceae sp. | 81 |

| OTU06 | DG02_1(66.7%) | Alphaproteobacteria | Allochromatium vinosum | 91 |

| OTU07 | QC04(100%) | Betaproteobacteria | Macromonas sp. | 91 |

| OTU08 | QC05(20.7%)/ QZM06(42.9%) | Betaproteobacteria | Curvibacter sp. | 96 |

| OTU09 | DG02_2(88.9%)/ DG02_5(65.0%) | Gammaproteobacteria | Allochromatium vinosum | 91 |

| OTU10 | QSYB09_2(32.3%) | Betaproteobacteria | Azonexus hydrophilus | 93 |

| OTU11 | DG01_6(31.8%) | Alphaproteobacteria | Thiomonas sp. | 91 |

| OTU12 | DG01_3(70.6%) | Alphaproteobacteria | Leptothrix mobilis | 85 |

| OTU13 | SM01(72.4%) | Betaproteobacteria | Macromonas sp. | 91 |

| OTU14 | DG01_5(39.5%)/ DG02_1(26.7%) | Betaproteobacteria | Thiobacillus thioparus | 82 |

| OTU16 | DG01_1(22.7%) | Alphaproteobacteria | Hydrogenophaga sp. | 93 |

| OTU18 | DG01_2(27.0%) | Betaproteobacteria | Elioraea sp. | 94 |

| OTU19 | QZM02(20.0%)/ QZM06(30.6%) | Betaproteobacteria | Sideroxydans sp. | 89 |

| OTU25 | QSYB08(41.9%) | Gammaproteobacteria | Thiothrix sp. | 90 |

| OTU27 | QSYB09_3(21.1%) | Betaproteobacteria | Thiobacillus thioparus | 78 |

| OTU32 | DG01_5(36.8%) | Alphaproteobacteria | Elioraea sp. | 94 |

| OTU38 | QSYB09_2(29.0%) | Gammaproteobacteria | Sulfurivermis fontis | 97 |

| OTU39 | QZM06(42.9%) | Betaproteobacteria | Candidimonas nitroreducens | 82 |

| OTU41 | DG01_1(22.7%) | Alphaproteobacteria | Paracoccus aestuarii | 89 |

| OTU42 | DG01_2(24.3%) | Alphaproteobacteria | Tabrizicola sp. | 96 |

| OTU43 | DG1_1(36.4%) | Betaproteobacteria | Blastomonas sp. | 93 |

| OTU44 | QZM02(50.0%) | Betaproteobacteria | Azospira oryzae | 78 |

| OTU54 | QSYB09_3(55.3%) | Betaproteobacteria | Hydrogenophaga sp. | 93 |

| OTU55 | QSYB09_2(25.8%) | Betaproteobacteria | Macromonas sp. | 91 |

| OTU58 | QZM04(36.1%) | Betaproteobacteria | Hydrogenophaga sp. | 94 |

| OTU59 | QZM02(20.0%) | Betaproteobacteria | Tibeticola sediminis | 99 |

| OTU61 | QSYB10(35.9%) | Betaproteobacteria | Comamonadaceae sp. | 95 |

| OTU62 | QSYB08(29.0%) | Betaproteobacteria | Vitreoscilla filiformis | 85 |

| OTU68 | QC05(20.7%) | Betaproteobacteria | Halochromatium salexigens | 90 |

| OTU77 | QC2(22.2%) | Alphaproteobacteria | Rhodobacter aestuarii | 90 |

| OTU78 | QC2(55.6%) | Alphaproteobacteria | Pseudorhodoplanes sinuspersici | 76 |

| OTU79 | QC2(22.2%) | Alphaproteobacteria | Pseudorhodoplanes sinuspersici | 91 |

2.3 统计分析

聚类分析的结果显示,QSYB10、QSYB09_3、QSYB08、QC02、QC04、DG02和DG12等7个热泉样点全部单独聚在一起,其他热泉样点则较为分散。Mantel检测结果显示,硫氧化细菌群落组成与温度、电导率、海拔、TDS和pH (P < 0.01)均呈显著(P < 0.05)相关性,其中海拔的相关系数最高(表 4)。

| Environmental factor | R | P |

| T | 0.142 | < 0.015 |

| EC | 0.142 | < 0.07 |

| Altitude | 0.246 | < 0.001 |

| TDS | 0.141 | < 0.001 |

| pH | 0.196 | < 0.001 |

| DOC | 0.070 | 0.136 |

| TOC | -0.041 | 0.709 |

| Fe(Ⅱ) | 0.112 | 0.091 |

| Sulfide | 0.130 | 0.032 |

α-多样性指数(Chao_1、Shannon_H、Simpson_1-D)与环境变量的Pearson相关性分析结果显示,Shannon指数与DOC浓度(R = 0.489,P < 0.05)呈显著正相关,Simpson指数与DOC浓度(R = 0.55,P < 0.015)呈显著正相关。

3 讨论目前针对热泉总细菌和古菌多样性研究较多,但针对热泉生境硫氧化群多样性的研究相对较少。本研究热泉样点中硫氧化细菌群落主要以α-Proteobacteria、β-Proteobacteria和γ-Protobacteria三个纲为主,暗示变形菌门的硫氧化细菌是该研究热泉中硫氧化过程中的主要参与者。前人研究结果显示,携带soxB基因的硫氧化菌主要为绿菌纲(Chlorobia)、α-Proteobacteria、β-Proteobacteria和γ-Protobacteria纲[8]。因此,本研究与前人的研究发现一致。

β-Proteobacteria纲硫氧化菌是本研究热泉样点的主要群落,少量热泉样点中的硫氧化细菌群落以α-Proteobacteria纲或γ-Proteobacteria纲为主(图 3)。我们研究结果与前人在其他热环境的研究结果不一致,如深海热液环境(硫氧化细菌群落以ε-变形菌纲和γ-变形菌纲为主)[37-38]。造成这种差异的原因主要是由于陆地热泉独特的地质条件和理化性质而导致。由于该研究的西藏热泉是陆地热泉,其地质条件和深海热液环境具有本质区别;而且不同热区系统具有不同的水-岩相互作用,因而导致不同热区系统的地球化学特征具有较大差异[39-40]。因此,陆地和海底热区的地球化学条件差异直接导致本研究的主要硫氧化菌群与前人研究的研究结果不同。另外,值得注意的是本研究的热泉沉积物中优势硫氧化细菌种群在不同热泉间差异较大(表 3)。该研究结果暗示硫氧化菌群敏感地响应热泉地球环境条件,因为我们研究的热泉样点在地球化学方面可能存在独立性(表 1)。此外,热泉之间的相互环境和地理隔离也有可能导致上述优势硫氧化细菌群落差异[41-42]。

该研究热泉样品的溶解有机碳含量显著(P < 0.05)影响着硫氧化菌群α多样性,即溶解有机碳含量越高,硫氧化菌群的α多样性越高。前人研究显示硫氧化菌主要以异养为主[8]。环境中有机碳可作为异养微生物的食物,因而直接影响着异养微生物的生长[43]。因此,溶解有机碳含量会影响研究热泉的硫氧化菌群α多样性。

温度、pH、电导率、总溶解性固体(TDS)、硫化物含量以及海拔对研究样品的硫氧化菌群落组成具有显著影响(表 4)。我们研究结果与前人大量研究总细菌和古菌群落组成分布的结果一致[44-47]。就温度而言,微生物个体有不同的最适生长温度和生长温度上限,温度高于或者低于最适生长温度都会抑制菌株的生长,超过生长上限菌株死亡或休眠[48-50]。其他环境中的硫氧化微生物群落组成也明显受到温度的影响[51-52]。就pH而言,极端酸度可能抑制硫氧化过程[53]。前人对Rhizobium sp.属硫氧化细菌株的研究结果表明,pH偏酸性时,菌株生长受抑制。菌株在中性条件或弱碱性条件下生长良好且能高效进行硫氧化功能,pH = 8.0时菌株硫氧化效率最高[54]。pH可能通过影响微生物细胞凋亡[55]、环境中离子浓度[56]、细胞膜完整性[57]等来影响微生物群落组成。电导率以及TDS与盐度有相关关系,因此,电导率和TDS可能均体现的是盐度对研究样品硫氧化菌群组成的影响[25]。硫化物是硫氧化的底物,因此,它影响研究样品的硫氧化菌群落组成是合理的[58]。

另外值得注意的是,海拔对研究热泉样品的硫氧化菌群落组成的影响高于其他环境参数(表 4)。该结果可能归因于海拔体现了地理和环境因素差异两个方面的综合因素。本研究热泉样点不同地区具有不同海拔平均值(表 1)。即平均海拔打加(DG) > 曲才(QC) > 曲卓木(QZM) > 曲色涌巴(QSYB) > 色米(SM)。前人大量研究揭示地理隔离对热泉微生物分布具有重要影响,不同热泉中微生物群落形成清晰不同的地理群落[45],没有物质交换的不同地区的热泉中变形菌门存在明显的遗传学差异[59-60]。本研究也显示距离较远的曲色涌巴(QSYB)、曲才(QC)、曲卓木(QZM)、色米(SM)采样点之间,完全没有相同的OTU存在,这三个地区中存在温度、pH等其他理化条件较为相近的采样点,但它们之间仍没有相同OTU存在。同时,相距较近的打加(DG)样点之间,存在相同OTU,所有样点呈现较为明显的地理分区,所以地理隔离对西藏热泉硫氧化细菌群落差异有较大影响。另外,海拔可以影响高原热泉水体溶氧浓度[61],即随着海拔增高,溶解进入热泉的氧气也越少。加之本研究热泉样点位于西藏高海拔地区,氧气比较稀薄。因此,溶解氧含量可能更加敏感地影响着研究热泉微生物的有氧代谢过程(如硫氧化)。由于本研究并未测试热泉溶解氧含量,所以以上推论有待后续研究证实。

4 结论西藏地区热泉中硫氧化细菌的群落主要属于由α-Proteobacteria、β-Proteobacteria和γ-Proteobacteria纲。且不同采样点的优势硫氧化细菌种群差异明显,大多数样点的优势硫氧化细菌群落为β-Proteobacteria,少量样点以α-Proteobacteria和γ-Proteobacteria为主。本研究中的西藏热泉硫氧化细菌群落分布特征主要受控于各种地理和环境条件,如海拔、温度、pH、总溶解固体(TDS)和电导率,其中海拔的影响强度相对其他环境因素较强。

| [1] | Jacob C, Giles GI, Giles NM, Sies H. Sulfur and selenium: the role of oxidation state in protein structure and function. Angewandte Chemie International Edition, 2003, 42(39): 4742-4758. DOI:10.1002/(ISSN)1521-3773 |

| [2] | Canfield DE, Kristensen E, Thamdrup B. The sulfur cycle. Advances in Marine Biology, 2005, 48: 313-381. DOI:10.1016/S0065-2881(05)48009-8 |

| [3] | Hurtgen MT, Pruss SB, Knoll AH. Evaluating the relationship between the carbon and sulfur cycles in the later Cambrian ocean: An example from the Port au Port Group, western Newfoundland, Canada. Earth and Planetary Science Letters, 2009, 281(3/4): 288-297. |

| [4] | 陆栋.硫杆菌分离鉴定及无机硫氧化系统研究.兰州大学硕士学位论文, 2006. |

| [5] | Lens PN, Kuenen JG. The biological sulfur cycle: novel opportunities for environmental biotechnology. Water Science and Technology, 2001, 44(8): 57-66. DOI:10.2166/wst.2001.0464 |

| [6] | Mukhopadhyaya PN, Deb C, Lahiri C, Roy P. A soxA gene, encoding a diheme cytochrome c, and a sox locus, essential for sulfur oxidation in a new sulfur lithotrophic bacterium. Journal of Bacteriology, 2000, 182(15): 4278-4287. DOI:10.1128/JB.182.15.4278-4287.2000 |

| [7] | Rother D, Henrich HJ, Quentmeier A, Bardischewsky F, Friedrich CG. Novel genes of the sox gene cluster, mutagenesis of the flavoprotein SoxF, and evidence for a general sulfur-oxidizing system in Paracoccus pantotrophus GB17. Journal of Bacteriology, 2001, 183(15): 4499-4508. DOI:10.1128/JB.183.15.4499-4508.2001 |

| [8] | Meyer B, Imhoff JF, Kuever J. Molecular analysis of the distribution and phylogeny of the soxB gene among sulfur-oxidizing bacteria - evolution of the Sox sulfur oxidation enzyme system. Environmental Microbiology, 2010, 9(12): 2957-2977. |

| [9] | Grimm F, Franz B, Dahl C. Thiosulfate and sulfur oxidation in purple sulfur bacteria//Dahl C, Friedrich CG. Microbial Sulfur Metabolism. Berlin Heidelberg: Springer, 2008. |

| [10] | Anandham R, Indiragandhi P, Madhaiyan M, Ryu KY, Jee HJ, Sa TM. Chemolithoautotrophic oxidation of thiosulfate and phylogenetic distribution of sulfur oxidation gene (soxB) in rhizobacteria isolated from crop plants. Research in Microbiology, 2008, 159(9/10): 579-589. |

| [11] |

He PQ, Zilda DS, Li J, Zhang XL, Cui JJ, Bai YZ, Patantis G, Chasanah E. Diversity of microbe and hydrogenase genes from a coastal hot spring of Kalianda, Indonesia. Acta Oceanologica Sinica, 2016, 38(6): 119-129.

(in Chinese) 何培青, Zilda DS, 李江, 张学雷, 崔菁菁, 白亚之, Patantis G, Chasanah E. 印度尼西亚卡利安达岛近岸热泉微生物和氢酶基因的多样性. 海洋学报, 2016, 38(6): 119-129. DOI:10.3969/j.issn.0253-4193.2016.06.013 |

| [12] | Tourova TP, Slobodova NV, Bumazhkin BK, Kolganova TV, Muyzer G, Sorokin DY. Analysis of community composition of sulfur-oxidizing bacteria in hypersaline and soda lakes using soxB as a functional molecular marker. FEMS Microbiology Ecology, 2013, 84(2): 280-289. DOI:10.1111/femsec.2013.84.issue-2 |

| [13] | Huber JA, Butterfield DA, Baross JA. Bacterial diversity in a subseafloor habitat following a deep-sea volcanic eruption. FEMS Microbiology Ecology, 2003, 43(3): 393-409. DOI:10.1111/fem.2003.43.issue-3 |

| [14] | Shock EL, Holland M, Meyer-Dombard D, Amend JP, Osburn GR, Fischer TP. Quantifying inorganic sources of geochemical energy in hydrothermal ecosystems, Yellowstone National Park, USA. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta, 2010, 74(14): 4005-4043. DOI:10.1016/j.gca.2009.08.036 |

| [15] | Konhauser KO, Jones B, Reysenbach AL, Renaut RW. Hot spring sinters: keys to understanding Earth's earliest life forms. Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences, 2003, 40(11): 1713-1724. DOI:10.1139/e03-059 |

| [16] | Hou WG, Wang S, Dong HL, Jiang HC, Briggs BR, Peacock JP, Huang QY, Huang LQ, Wu G, Zhi XY, Li WJ, Dodsworth JA, Hedlund BP, Zhang CL, Hartnett HE, Dijkstra P, Hungate BA. A comprehensive census of microbial diversity in hot springs of Tengchong, Yunnan Province China using 16S rRNA gene pyrosequencing. PLoS One, 2013, 8(1): e53350. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0053350 |

| [17] | Wang S, Hou WG, Dong HL, Dong HC, Jiang HC, Huang LQ, Wu G, Zhang CL, Song ZQ, Zhang Y, Ren HL, Zhang J, Zhang L. Control of temperature on microbial community structure in hot springs of the Tibetan plateau. PLoS One, 2013, 8(5): e62901. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0062901 |

| [18] |

Bai JQ, Mei L, Yang ML. Geothermal resources and crustal thermal structure of the qinghai-tibet plateau. Journal of Geomechanics, 2006, 12(3): 354-362.

(in Chinese) 白嘉启, 梅琳, 杨美伶. 青藏高原地热资源与地壳热结构. 地质力学学报, 2006, 12(3): 354-362. DOI:10.3969/j.issn.1006-6616.2006.03.010 |

| [19] |

Sun HL, Ma F, Lin WJ, Liu Z, Wang GL, Nan DW. Geochemical characteristics and geothermometer application in high temperature geothermal field in Tibet. Geological Science and Technology Information, 2015, 34(3): 171-177.

(in Chinese) 孙红丽, 马峰, 蔺文静, 刘昭, 王贵玲, 男达瓦. 西藏高温地热田地球化学特征及地热温标应用. 地质科技情报, 2015, 34(3): 171-177. |

| [20] | Huang QY, Dong CZ, Dong RM, Jiang HC, Wang S, Wang GH, Fang B, Ding XX, Niu L, Li X, Zhang CL, Dong HL. Archaeal and bacterial diversity in hot springs on the Tibetan Plateau, China. Extremophiles, 2011, 15(5): 549-563. DOI:10.1007/s00792-011-0386-z |

| [21] | Wang S, Hou WG, Dong HL, Jiang HC, Huang LQ, Wu G, Zhang CL, Song ZQ, Zhang Y, Ren HL, Zhang J, Zhang L. Control of temperature on microbial community structure in hot springs of the Tibetan Plateau. PLoS One, 2013, 8(5): 62901. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0062901 |

| [22] | Song ZQ, Wang FP, Zhi XY, Chen JQ, Zhou EM, Liang F, Xiao X, Tang SK, Jiang HC, Zhang CL, Dong H, Li WJ. Bacterial and archaeal diversities in Yunnan and Tibetan hot springs, China. Environmental Microbiology, 2012, 15(4): 1160-1175. |

| [23] | Jiang HC, Dong HL, Zhang GX, Yu BS, Chapman LR, Fields MW. Microbial diversity in water and sediment of Lake Chaka, an athalassohaline lake in northwestern China. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 2006, 72(6): 3832-3845. DOI:10.1128/AEM.02869-05 |

| [24] | Petri R, Podgorsek L, Imhoff JF. Phylogeny and distribution of the soxB gene among thiosulfate-oxidizing bacteria. FEMS Microbiology Letters, 2001, 197(2): 171-178. DOI:10.1111/fml.2001.197.issue-2 |

| [25] | Yang J, Jiang HC, Dong HL, Wu G, Hou WG, Zhao WY, Sun YJ, Lai ZP. Abundance and diversity of sulfur-oxidizing bacteria along a salinity gradient in four Qinghai-Tibetan Lakes, China. Geomicrobiology Journal, 2013, 30(9): 851-860. DOI:10.1080/01490451.2013.790921 |

| [26] | Blackwood CB. Analysing microbial community structure by means of terminal restriction fragment length polymorphism (T-RFLP)//Cooper JE, Rao JR. Molecular Approaches to Soil, Rhizosphere and Plant Microorganism Analysis. Cambridge: CAB International, 2006. |

| [27] | Schloss PD, Westcott SL, Ryabin T, Hall JR, Hartmann M, Hollister EB, Lesniewski RA, Oakley BB, Parks DH, Robinson CJ, Sahl JW, Stres B, Thallinger GG, van Horn DJ, Weber CF. Introducing mothur: open-source, platform-independent, community-supported software for describing and comparing microbial communities. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 2009, 75(23): 7537-7541. DOI:10.1128/AEM.01541-09 |

| [28] | Khan IU, Habib N, Xiao M, Li MM, Xian WD, Hejazi MS, Tarhriz V, Zhi XY, Li WJ. Rhodobacter thermarum sp. nov., a novel phototrophic bacterium isolated from sediment of a hot spring. Antonie van Leeuwenhoek, 2019: 1-9. DOI:10.1007/s10482-018-01219-7 |

| [29] | Ramana VR, Kumar AK, Srinivas TNR, Sasikala C, Ramana CV. Rhodobacter aestuarii sp. nov., a phototrophic alphaproteobacterium isolated from an estuarine environment. International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology, 2009, 59(5): 1133-1136. DOI:10.1099/ijs.0.004507-0 |

| [30] | 罗剑飞.硫氧化菌群落结构分析及其特性研究.华南理工大学博士学位论文, 2011. |

| [31] | Albuquerque L, Rainey FA, Pena A, Tiago I, Veríssimo A, Nobre MF, Da Costa MS. Tepidamorphus gemmatus gen. nov., sp. nov., a slightly thermophilic member of the Alphaproteobacteria. Systematic and Applied Microbiology, 2010, 33(2): 60-66. DOI:10.1016/j.syapm.2010.01.002 |

| [32] | Tirandaz H, Dastgheib SM, Amoozegar MA, Shavandi M, de La Haba RR, Ventosa A. Pseudorhodoplanes sinuspersici gen. nov., sp. nov., isolated from oil-contaminated soil. Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology, 2015, 65(12): 4743-4748. DOI:10.1099/ijsem.0.000643 |

| [33] | Tourna M, Maclean P, Condron L, O'Callaghan M, Wakelin SA. Links between sulphur oxidation and sulphur-oxidising bacteria abundance and diversity in soil microcosms based on soxB functional gene analysis. FEMS Microbiology Ecology, 2014, 88(3): 538-549. DOI:10.1111/fem.2014.88.issue-3 |

| [34] | Drobner E, Huber H, Rachel R, Stetter KO. Thiobacillus plumbophilus spec. nov., a novel galena and hydrogen oxidizer. Archives of Microbiology, 1992, 157(3): 213-217. DOI:10.1007/BF00245152 |

| [35] | Strohl WR, Schmidt TM, Lawry NH, Mezzino MJ, Larkin JM. Characterization of Vitreoscilla beggiatoides and Vitreoscilla filiformis sp. nov., nom. rev., and comparison with Vitreoscilla stercoraria and Beggiatoa alba. International Journal of Systematic Bacteriology, 1986, 36(2): 302-313. DOI:10.1099/00207713-36-2-302 |

| [36] | Kojima H, Watanabe M, Fukui M. Sulfurivermis fontis gen. nov., sp. nov., a sulfur-oxidizing autotroph, and proposal of Thioprofundaceae fam. nov. International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology, 2017, 67(9): 3458-3461. DOI:10.1099/ijsem.0.002137 |

| [37] |

Xu HX, Jiang LJ, Li SN, Zhong TH, Lai QL, Shao ZZ. Diversity of culturable sulfur-oxidizing bacteria in deep-sea hydrothermal vent environments of the South Atlantic. Acta Microbiologica Sinica, 2016, 56(1): 88-100.

(in Chinese) 徐鈜绣, 姜丽晶, 李少能, 钟添华, 赖其良, 邵宗泽. 南大西洋深海热液区可培养硫氧化微生物多样性及其硫氧化特性. 微生物学报, 2016, 56(1): 88-100. |

| [38] |

Zeng X, Shao ZZ. Microbial functional groups and molecular mechanisms for biomineralization in hydrothermal vents. Microbiology China, 2017, 44(4): 890-901.

(in Chinese) 曾湘, 邵宗泽. 深海热液区微生物矿化过程的功能群和分子机制. 微生物学通报, 2017, 44(4): 890-901. |

| [39] | 刘明亮.不同热源类型地热系统的地球化学对比.中国地质大学硕士学位论文, 2015. |

| [40] |

Liu ML, Cao YW, Wang MD, Li JX, Guo QH. Source of hydrochemical composition and formation mechanism of Rehai geothermal water in Tengchong. Safety and Environmental Engineering, 2014, 21(6): 1-7.

(in Chinese) 刘明亮, 曹耀武, 王敏黛, 李洁祥, 郭清海. 腾冲热海热泉水化学组分来源及其形成机制探讨. 安全与环境工程, 2014, 21(6): 1-7. DOI:10.3969/j.issn.1671-1556.2014.06.001 |

| [41] | Valverde A, Tuffin M, Cowan DA. Biogeography of bacterial communities in hot springs: a focus on the actinobacteria. Extremophiles, 2012, 16(4): 669-679. DOI:10.1007/s00792-012-0465-9 |

| [42] | Whitaker RJ, Grogan DW, Taylor JW. Geographic barriers isolate endemic populations of hyperthermophilic archaea. Science, 2003, 301(5635): 976-978. DOI:10.1126/science.1086909 |

| [43] | Imhoff JF. Taxonomy and physiology of phototrophic purple bacteria and green sulfur bacteria//Blankenship RE, Madigan MT, Bauer CE. Anoxygenic Photosynthetic Bacteria. Dordrecht: Springer, 1995. |

| [44] |

Huang QY, Jiang HC, Zhang CL, Li WJ, Deng SC, Yu BS, Dong HL. Abundance of ammonia-oxidizing microorganisms in response to environmental variables of hot springs in Yunnan Province, China. Acta microbiologica Sinica, 2010, 50(1): 132-136.

(in Chinese) 黄秋媛, 蒋宏忱, 张传伦, 李文均, 邓诗财, 于炳松, 董海良. 云南地区热泉中氨氧化菌丰度对环境条件的响应. 微生物学报, 2010, 50(1): 132-136. |

| [45] | Zhang CL, Ye Q, Huang ZY, Li WJ, Chen JQ, Song ZQ, Zhao WD, Bagell C, Inskeep WP, Ross C, Gao L, Wiegel J, Romanek CS, Shock EL, Hedlund BP. Global occurrence of archaeal amoA genes in terrestrial hot springs. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 2008, 74(20): 6417-6426. DOI:10.1128/AEM.00843-08 |

| [46] |

Song ZQ, Wang L, Zhou EM, Wang FP, Xiao X, Zhang CL, Li WJ. Abundances of ammonia-oxidizing archaeal accA and amoA genes in response to NO2- and NO3- of hot springs in Yunnan province. Acta Microbiologica Sinica, 2014, 54(12): 1462-1470.

(in Chinese) 宋兆齐, 王莉, 周恩民, 王风平, 肖湘, 张传伦, 李文均. 云南热泉中氨氧化古菌的accA基因与amoA基因丰度与环境因子NO2-和NO3-的相关性. 微生物学报, 2014, 54(12): 1462-1470. |

| [47] | Huang QY, Jiang HC, Briggs BR, Wang S, Hou WG, Li GY, Wu G, Solis R, Arcilla CA, Abrajano T, Dong H. Archaeal and bacterial diversity in acidic to circumneutral hot springs in the Philippines. FEMS Microbiology Ecology, 2013, 85(3): 452-464. DOI:10.1111/1574-6941.12134 |

| [48] | Robertson WJ, Kinnunen HM, Plumb JJ, Franzmann PD, Puhakka JA, Gibson JAE, Nichols PD. Moderately thermophilic iron oxidising bacteria isolated from a pyritic coal deposit showing spontaneous combustion. Minerals Engineering, 15(11): 815-822. DOI:10.1016/S0892-6875(02)00130-9 |

| [49] | De Boer MK, Koolmees EM, Vrieling EG, Breeman AM, Van Rijssel M. Temperature responses of three Fibrocapsa japonica strains (Raphidophyceae) from different climate regions. Journal of Plankton Research, 2005, 27(1): 47-60. |

| [50] | Bogdanova TI, Tsaplina I, Kondrat'eva TF, Duda VI, Suzina NE, Melamud VS, Tourova TP, Karavaiko GI. Sulfobacillus thermotolerans sp. nov., a thermotolerant, chemolithotrophic bacterium. International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology, 2006, 56(5): 1039-1042. DOI:10.1099/ijs.0.64106-0 |

| [51] | Lin YT, Jia ZJ, Wang DM, Chiu CY. Effects of temperature on the composition and diversity of bacterial communities in bamboo soils at different elevations. Biogeosciences, 2017, 14(21): 4879-4889. DOI:10.5194/bg-14-4879-2017 |

| [52] | 王尚.滇藏热泉微生物群落分布及其控制因素研究.中国地质大学(北京)博士学位论文, 2015. |

| [53] | Dick RP, Deng S. Multivariate factor analysis of sulfur oxidation and rhodanese activity in soils. Biogeochemistry, 1991, 12(2): 87-101. |

| [54] |

Wang HX, Jiang LY, Wu XW, Chen JM. Isolation, identification and degradation characteristics of a sulfide-oxidizing bacterium. Applied and Environmental Biology, 2011, 17(5): 706-710.

(in Chinese) 王惠祥, 姜理英, 吴晓薇, 陈建孟. 硫氧化细菌的分离鉴定及降解特性. 应用与环境生物学报, 2011, 17(5): 706-710. |

| [55] | Lagadic-Gossmann D, Huc L, Lecureur V. Alterations of intracellular pH homeostasis in apoptosis: origins and roles. Cell Death and Differentiation, 2004, 11(9): 953-961. DOI:10.1038/sj.cdd.4401466 |

| [56] | Suzuki I, Lee D, Mackay B, Harahuc L, Oh JK. Effect of various ions, pH, and osmotic pressure on oxidation of elemental sulfur by Thiobacillus thiooxidans. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 1999, 65(11): 5163-5168. |

| [57] | Chen RJ, Yue ZL, Eccleston ME, Williams S, Slater NK. Modulation of cell membrane disruption by pH-responsive pseudo-peptides through grafting with hydrophilic side chains. Journal of the Controlled Release, 2005, 108(1): 63-72. DOI:10.1016/j.jconrel.2005.07.011 |

| [58] |

Zhang J, Fan WP, Fang P, Xia CC. Effect of substrates on bio-oxidation catalyzed by T. ferrooxidans. Journal of Nanjing University of Chemical Technology, 2001, 23(6): 37-41.

(in Chinese) 张俊, 范伟平, 方苹, 夏场场. 底物对亚铁硫杆菌生物氧化过程的影响. 南京工业大学学报, 2001, 23(6): 37-41. DOI:10.3969/j.issn.1671-7627.2001.06.009 |

| [59] |

Zhang S, Yan L, Chen ZB. Geographical distribution of sulfur-oxidizing bacteria. Journal of Heilongjiang Bayi Agricultural University, 2017, 29(2): 68-73.

(in Chinese) 张爽, 晏磊, 陈志宝. 硫氧化菌的地域分布特征. 黑龙江八一农垦大学学报, 2017, 29(2): 68-73. DOI:10.3969/j.issn.1002-2090.2017.02.014 |

| [60] |

Song ZQ, Wang L, Liu XH, Liang F. The diversities of Proteobacteria in four acidic hot springs in Yunnan. Journal of Henan Agricultural University, 2016, 50(3): 376-382.

(in Chinese) 宋兆齐, 王莉, 刘秀花, 梁峰. 云南4处酸性热泉中的变形菌门细菌多样性. 河南农业大学学报, 2016, 50(3): 376-382. |

| [61] |

Lu LL, Li ZX, Cui CY. Study on the variation of dissolved oxygen in the Plateau river. Environmental Science and Technology, 2018, 41(7): 133-140.

(in Chinese) 吕琳莉, 李朝霞, 崔崇雨. 高原河流溶解氧变化规律研究. 环境科学与技术, 2018, 41(7): 133-140. |

2019, Vol. 59

2019, Vol. 59