中国科学院微生物研究所,中国微生物学会,中国菌物学会

文章信息

- 高杰, 何肖龙, 曹虹. 2018

- Jie Gao, Xiaolong He, Hong Cao. 2018

- 后生元(postbiotics):调节肝硬化患者肠道菌群及疾病进程的新策略

- Postbiotics: a new orientation for modulation of the gut dysbiosis in liver cirrhosis

- 微生物学报, 58(11): 1938-1949

- Acta Microbiologica Sinica, 58(11): 1938-1949

-

文章历史

- 收稿日期:2018-05-01

- 修回日期:2018-06-29

- 网络出版日期:2018-07-30

2. 南方医科大学公共卫生学院, 广东省热带病研究重点实验室, 微生物学系, 广东 广州 510515

2. Key Laboratory of Tropical Diseases Research in Guangdong, School of Public Health, Department of Microbiology, Southern Medical University, Guangzhou 510515, Guangdong Province, China

肝硬化是各种慢性炎性肝病的最终环节,其主要病因包括病毒性肝炎、酒精性肝炎、非酒精性脂肪性肝炎以及各种免疫性肝病。肝硬化已成为全球疾病负担最重的疾病之一,2015年,肝硬化成为全球第11位的致死性疾病。在美国,肝硬化每年的住院人次数约为690000,总费用高达10亿美元[1-2]。肝硬化在中国也是主要的疾病负担之一[3]。引起肝硬化患者住院的重要原因是失代偿事件的发生,如大量腹水、感染、肝性脑病及慢加急性肝衰竭等[2, 4]。

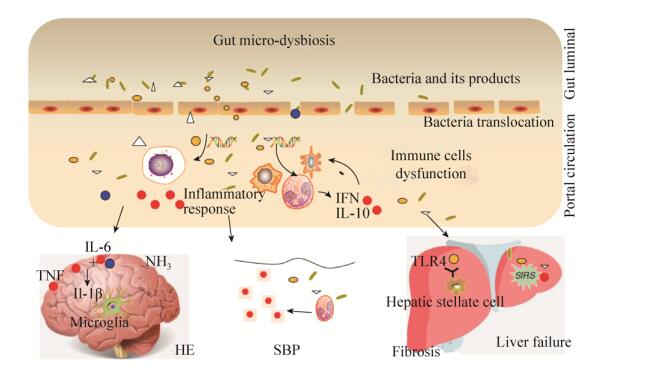

近年来,越来越多的研究表明,肠道菌群与肝硬化患者并发症以及疾病进程有明确的关系。在肝硬化患者中,肠道菌群失调、肠道屏障损伤和机体免疫力低下共同导致肠道菌群移位,使得其与机体间的相互作用从生理性逐渐转向病理性[5-6]。许多研究表明,肝硬化患者肠道菌群失调与其疾病进展及并发症的出现有一定因果关系。肝硬化肠道菌群失调在肝纤维进展、肝硬化并发症如自发性细菌性腹膜炎(spontaneous bacterial peritonitis,SBP)、肝性脑病(hepatic encephalopathy,HE)和慢加急性肝衰竭方面均有重要的作用[7-11]。

目前,针对肝硬化肠道菌群失调的治疗方式很多,如抗生素、粪菌移植、β受体阻滞剂、益生菌等,这些方法均在临床研究中呈现一定的疗效,但同时也存在一些局限性,如抗生素易诱发新的肠道菌群失调,益生菌的生物利用度难以明确等[2, 12]。一些新的治疗方向逐渐涌现,如有类似益生菌益生功效的益生菌组分和(或)代谢产物(后生元)[13-14],其在肝硬化患者中有巨大的潜在治疗价值,有望改善肝硬化肠道菌群失调现状及延缓疾病进程,减少后续并发症出现。

本文主要总结肠道菌群失调与肝硬化并发症之间的关系,并重点讨论后生元这类新型的益生菌组分和(或)代谢产物在调节肝硬化肠道菌群及疾病进程中的应用前景。

1 肠道菌群失调与肝硬化并发症的关系肠道菌群失调是肝硬化患者普遍的特征,包括菌群丰度的减少和菌群种类的改变。Chen、Li、Baja[7, 15-16]及其团队证明,本土细菌在肝硬化患者中显著减少,而非本土细菌在肝硬化患者中增多。李兰娟[16]及其团队采用了宏基因组学分析的方法,阐明了肝硬化患者肠道菌群的特点,发现了75000个肠道菌群相关基因在肝硬化与健康人群中的分布显著不同。另外,不同于糖尿病、炎性肠病等其他菌群失调相关性疾病,肝硬化患者呈现其特征性的菌群分布特点,由此鉴定出了15个菌种,有望成为肝硬化的生物学标志物。

肠道菌群失调是肠道细菌移位的关键环节。细菌及其代谢产物经由受损的肠道屏障进入门脉系统,可引起血液循环中各种免疫细胞的激活,进而发生功能障碍。Jalan等证明,肝硬化患者中性粒细胞静息状态下氧暴反应增强,而杀菌功能、吞噬功能显著减弱,且这种功能障碍可以通过内毒素清除等方式得以修复[17-18]。Hackstein等也证明,循环及肝脏中的髓系免疫细胞不断受到移位的细菌及代谢产物的刺激,可以产生IFN及IL-10,这些炎症因子可以反过来抑制髓系细胞的免疫功能,而阻断IFN或IL-10受体可以重建髓系细胞的免疫功能[19]。以上研究证明,肠道移位的细菌及其代谢产物刺激循环中的免疫细胞,是肝硬化患者呈现系统性炎症反应及免疫瘫痪这样的免疫失调状态的基础。

肠道菌群失调与肝性脑病的发生也有密切的关系。研究表明,普氏菌属(Prevotella)、毛螺菌属(Lachnospiraceae)增多可预防肝性脑病的发生,而在产碱杆菌(Alcaligeneceae)、紫单胞菌(Porphyromonadaceae)、韦荣氏球菌(Veillonellaceae)、肠球菌(Enterococcus)、巨球型菌(Megasphaera)和伯克氏菌(Burkholderia)菌属丰度较高的患者中,肝性脑病更为常见[10, 20]。肠道菌群引起肝性脑病主要通过内毒素引发的系统性炎症反应与血浆氨的协同作用实现的。异位的肠道细菌及其代谢产物刺激机体产生炎症反应,IL-1β、TNF、IL-6等炎症因子跨过血脑屏障进入脑以后,与氨协同刺激小胶质细胞,使其产生CCl2,募集巨噬细胞等浸润,是发生肝性脑病的基础[21-22]。乳果糖及口服抗生素能减少肠道来源的氨产生及肝性脑病的发生,充分说明了肠道细菌在肝性脑病中的重要作用[23]。利福昔明及乳果糖除了改善肝性脑病外,还能在一定程度上改善肠道菌群。Baja等在20名肝硬化患者中证明,8周的利福昔明治疗能显著改善轻微肝性脑病患者的认知状态,同时对肠道菌群也有一定影响[24]。

肠道菌群的移位是自发性细菌性腹膜炎发生的关键机制。肠道细菌过度生长(intestinal bacterial overgrowth,IBO)的患者SBP的发生率显著高于无IBO的患者[24]。使用非吸收口服抗生素如诺氟沙星进行选择性肠道除菌能减轻SBP的发生及肝硬化患者的死亡率,但接受抗生素治疗的肝硬化患者容易发生多耐药菌感染,或引发新的肠道菌群失调如艰难梭菌性肠炎[25-26]。导致IBO发生的因素如质子泵抑制剂(proton pump inhibitor,PPI)的使用是SBP发生的危险因素,一项分析了8个研究(3815个病人)的Meta分析显示,使用PPI患者SBP的发生率是未使用PPI患者的3倍[27-28]。

肠道菌群失调与慢加急性肝衰竭的发生也有密切的关系。陈及其研究团队证明,肠道菌群失调情况是慢加急性肝衰竭预后的影响因素。慢加急性肝衰竭患者总体肠道菌群丰度显著低于对照组,其中拟杆菌(Bacteroidacea),疣微菌(Ruminococcaceae),以及毛螺菌(Lachnospiraceae)含量较低,而巴斯德菌(Pasteurellaceae),链球菌(Streptococcaceae),以及屎肠球菌(Enterecoccaceae)的含量较高。网络关系分析显示本土细菌数量与炎症因子有相关性。巴斯德氏菌(Pasteurellaceae)菌种数量和MELD积分是预后的独立危险因素[20]。肠道菌群失调与肝硬化并发症关系见图 1。

|

| 图 1 肠道菌群失调与肝硬化并发症的关系 Figure 1 The relationship between gut microbial dysbiosis and complication of liver cirrhosis. Gut dysbiosis, in combination with disruption of intestinal barrier can lead to translocation of bacteria and its products to portal circulation system, and systematic circulation, further arriving at peritoneal cavity, liver and brain, causing immune cell dysfunction, spontaneous bacterial peritonitis, liver fibrosis progression, liver failure and hepatic encephalopathy. |

2 后生元及其在调节肝硬化患者菌群失调中的应用前景

益生菌是治疗肝硬化患者肠道菌群失调的较有前景的方法之一。目前常见的益生菌种属包括乳杆菌属、双歧杆菌属。益生菌对于预防肝性脑病和SBP、减缓肝硬化病程、降低门脉高压均有一定作用[29-31],但是,以上益生菌对于肝硬化的作用效果均有争议[32-33],这可能与疾病的阶段、益生菌种类的选择以及疗程均有关系。另外,尽管益生菌在人体中即使肝硬化病人中都能良好耐受,仍有研究表明,在重症患者或者免疫力极度低下的患者中,益生菌可能导致益生菌的机会感染,甚至增加病死率[34-35]。近些年来,有类似益生菌益生功效的益生菌组分和(或)代谢产物(即后生元)[13-14]逐渐受到关注,其在肝硬化患者中有巨大的潜在治疗价值,有望改善肝硬化肠道菌群失调现状及延缓疾病进程,减少后续并发症出现。

2.1 后生元的定义目前已明确的益生菌肠道保护机制包括竞争性排除致病菌、调节和稳定肠道共生菌群、增强肠上皮屏障功能和调节肠粘膜免疫等[36]。这些益生机制的研究都是建立在一定数量的活菌基础上的。近年来,越来越多的研究发现,除了活菌体外,益生菌的代谢产物、裂解提取物、细胞壁组分甚至培养上清,也都能表现出明显的益生作用,且不同组分的益生作用机制各不相同[37]。然而,尽管在益生活菌功能研究的早期就有研究团队开始探讨非益生活菌组分的益生功效,但是到目前为止,这一类具有健康功效的组分仍未有正式命名。随着越来越多的非益生活菌成分被证明有促进健康的功效,指代这些益生成分的新词汇陆续出现,postbiotics、paraprobiotics、metabiotics、non-viable probiotics、inactived probiotics和ghost probiotic是目前出现的这类益生物质的代称,其中postbiotics一词由Tsilingiri等提出,是目前应用最为广泛的对这类益生物质的总称,中文名暂译为后生元。目前发现许多种类的后生元,包括短链脂肪酸、酶、多肽、内源或外源性聚糖、细胞表面蛋白、有机酸等,其益生功能包括但不限于抗菌、抗氧化、调节肠道屏障功能和免疫反应等。与益生菌体一样,现在postbiotic的研究多集中于乳酸杆菌和双歧杆菌。总的来说,后生元具有益生菌无法比拟的优点,包括明确的化学结构、安全的剂量参数和更长的保存期(作为营养添加剂,保存期可长达5年)。Shendeover等研究表明后生元具有很好的吸收性、代谢性和机体分布性[38]。使用后生元可以在获得益生菌类似益生功效的同时,避免了活菌本身生物利用度低、效果不稳定、易传递耐药基因等问题,将会是未来益生菌领域研究的新方向[38]。

2.2 后生元的益生作用 2.2.1 维持肠道菌群稳定: 肝硬化病人肠道菌群紊乱,条件致病菌增加,这些细菌的移位是肝硬化病人并发症发生的关键。益生菌可以通过分泌一些抑菌性物质选择性地抑制致病菌的生长。目前研究最多的益生菌是乳杆菌和双歧杆菌,这些细菌大多能产生酸性物质,如乳酸、乙酸、丙酸和正丁酸等,它们可以降低肠道的pH值,抑制多种致病菌的生长和繁殖,对周围的益生菌却没有影响,协助肠道内建立以益生菌为主导地位的微生态环境[39]。Kareem等发现植物乳杆菌RG11、RG14、RI11、UL4、TL1和RS5株的酸性培养上清能有效地抑制单核细胞增多性李斯特菌L-MS、肠沙门氏菌S-1000、大肠杆菌E-30和万古霉素抗性肠球菌的生长[40]。此外,研究发现乳酸菌在代谢过程中能产生过氧化氢,催化化学反应产生氧化性中间产物,抑制病原菌的生长和繁殖[41]。益生菌还能分泌另一类抑菌物质细菌素,如片球菌素、链球菌素等[42],具有广谱抑菌活性,能进入病原菌体内,破坏其遗传物质或重要的代谢途径,抑制细菌的生长和增殖。炎性肠病患者肠道中经常出现条件致病性肠杆菌的异常增殖,导致肠道菌群失调并引发严重的肠炎,Sassone-Corsi等研究发现一种新的抑菌物质——大肠杆菌Nissle 1917产生的Microin,它能有效地抑制条件致病性肠杆菌的异常生长,起到缓解肠炎的作用[43]。Levy等的研究发现,益生菌的代谢产物牛磺酸、组氨酸和精氨酸可以共调节肠道免疫细胞的NLRP6炎症小体,促进IL-18分泌和下游的抗菌肽产生,继而抑制致病菌生长,调节肠道菌群微环境的平衡[44]。此外,某些益生菌的后生元被证明可促进黏液素(mucin)和免疫球蛋白IgA的产生,如鼠李糖乳杆菌GG株(Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG,LGG)的p40,以及本实验室发现的一种LGG分泌蛋白[45-46]。这些蛋白可能促进了肠道菌群的建立,因为在肠道菌群建立的过程中,黏液素起到很重要的作用,它不仅能为肠道共生菌提供黏附位点,还能被共生菌分解为其提供营养来源[47]。另外,肠道固有层可分泌免疫球蛋白IgA,它是防止肠道致病菌入侵上皮屏障的重要因子。研究表明IgA可通过“免疫排斥”机制排除肠道中的致病菌,籍此促进肠道微生物菌群的形成并维持其多样性[48]。因此,具有促进mucin和IgA表达特性的后生元,很可能也促进了肠道菌群的形成和并保持其稳定性。

2.2.2 保护肠道上皮屏障功能: 肠上皮细胞及覆盖其表面的黏液层组成了肠道上皮屏障,是肠粘膜阻止致病菌入侵的主要防线。黏液层由杯状细胞分泌的黏液素形成,黏液是肠道蠕动的润滑剂,可促进肠道蠕动并裹挟致病菌排出体外[47]。当致病菌突破黏液层入侵肠上皮细胞时,mucin可向固有层的树突细胞传递识别的危险信号,激发黏膜免疫应答[47]。肠道屏障中的潘氏细胞可分泌β-防御素,抑制致病菌生长和入侵。肠道屏障的透通性低,其重要原因是肠上皮细胞间形成的紧密连接。紧密连接是位于肠上皮细胞顶端侧面的多蛋白复合体,主要包括紧密连接蛋白Zonula occludens、闭合蛋白Claudins、闭锁蛋白Occludins和连接黏附分子等各类结构蛋白及连接分子,它们维持了肠道屏障的闭合性,能有效地阻断病原菌的入侵。许多研究证实了后生元具有增强肠道上皮屏障功能的作用,如大肠杆菌Nissle 1917,一种常见的益生菌,可诱导β-防御素的分泌,起到保护肠上皮细胞的作用[49]。鼠李糖乳杆菌GG株的分泌蛋白p40是研究得较为深入的后生元,p40被证明能抑制葡聚糖硫酸钠和噁唑酮诱导的肠上皮细胞损伤[50-51],该机制是通过结合并激活EGF受体,减少细胞因子表达及诱导肠上皮细胞凋亡;该结论同样在体内研究中得到了证实。然而,有趣的是,LGG活菌体并不具有这种预防或者治疗作用[52]。某些益生菌的代谢产物能有效抑制有害物质引起的肠上皮细胞间紧密连接破坏、肠道通透性增加和肠上皮细胞凋亡。Wang等[53-54]发现LGG的培养上清可降低酒精对Caco-2细胞的损伤,还可拮抗酒精下调小鼠肠道上皮细胞间紧密连接蛋白claudin-1表达的作用,同时抑制酒精对肝脏的损伤。Prisciandaro等[55]报道大肠杆菌Nissle 1917和LGG的培养上清均能有效抑制5-氟尿嘧啶激活肠上皮细胞的Caspase 3和7,阻止上皮细胞的异常凋亡。 2.2.3 免疫调节作用: 后生元的益生作用并不局限于肠上皮细胞,它还能调节树突状细胞、淋巴细胞等免疫细胞的免疫反应。von Schillde等发现某种乳酸菌(Lactobacillus paracase)分泌一种丝氨酸蛋白酶Lactocepin,可裂解和灭活淋巴细胞趋化因子IP-10,减少小鼠肠炎模型中的炎症反应和淋巴细胞募集[56]。后生元如S层蛋白和聚糖A (polysaccharides,PSA)均可调节树突状细胞和T细胞的促炎和抑炎反应,保护肠炎模型中小鼠肠上皮细胞免于致病菌定殖和化学物质的损伤[57]。Menard等的研究发现,B. breve和嗜热链球菌分泌的代谢产物具有抗炎作用,体内研究证实,这两种细菌的混合培养上清可增强小鼠的肠道屏障功能并调节T辅助细胞的功能[58]。Fernandez等的研究表明,唾液乳杆菌(Lactobacillus salivarius)来源的肽聚糖能保护小鼠免于TNBS引起的肠炎,具体机制为肽聚糖结合NOD2受体,增加炎症区域IL-10的表达,同时调节肠系膜淋巴结中树突状细胞(CD103+)和T细胞(CD4+ Foxp3+)群体的免疫反应[59]。Hoarau等[60]研究了短双歧杆菌C50分泌的胞外蛋白,发现它可以促进人树突状细胞的成熟和激活,该功效是通过C50与TLR-2结合,继而激活MAPK、GSK3和PI3K信号通路,诱导IL-10、IL-12的分泌,最终促进LPS刺激下人树突状细胞的成熟和激活。 2.2.4 其他: 除了上述的益生作用外,后生元还被证明具有抗氧化作用。Xu等[61]发现动物双歧杆菌(Bifidobacterium animalis RH)产生的胞外多糖能抑制脂质过氧化反应和增强自由基清除能力(羟基自由基和超氧根自由基)。Li等[62]发现瑞士乳杆菌(Lactobacillus helveticus MB2-1)粗提取和纯化的胞外多糖,均能展示出很强的自由基清除能力和去除亚铁离子能力。此外,一些益生菌的细胞壁组分如脂磷壁酸质类,被发现具有抗肿瘤、抗氧化和免疫调节功能[63]。有趣的是,研究发现许多益生菌的后生元还显示出了肝保护性。如Dinic等[64]的研究发现,发酵乳杆菌(Lactobacillus fermentum BGHV110)的裂解液上清能抑制乙酰氨基酚对HepG2细胞的毒性,其机理是通过介导PINK1信号途径激活细胞的自噬反应。在另一相关的研究中,Sharma等[65]报道了乳酸肠球菌(Enterococcis lactis IITRHR1)和嗜乳酸杆菌(Lactobacillus acidophilus MTCC447)的胞内组分同样可以抑制乙酰氨基酚引起大鼠肝细胞的毒性。有趣的是,该作者还发现这些后生元能回复肝细胞的谷胱甘肽水平并减少氧化应激标志物水平。图 2是目前发现的后生元种类及其相关的益生作用图。2.3 后生元在肝硬化肠道屏障损伤中的防治作用前景

鉴于后生元在肠道屏障中的重要益生作用,研究后生元在肠道菌群紊乱相关疾病中的治疗效果成为了新的研究趋势和热点。现在,已有许多课题组研究了后生元的肠道菌群紊乱相关疾病治疗前景。Sokol等[66]研究了普拉梭菌(Faecalibacterium prausnitzii)的后生元益生功效,发现该益生菌的培养上清能有效治疗克罗恩病引起的肠道菌群紊乱并抑制肠道炎症。Sassone-Corsi等[43]的研究发现大肠杆菌Nissle 1917产生的后生元Microin能明显抑制肠道炎症条件下致病性肠杆菌的异常增生,缓解肠道菌群紊乱,最终起到治疗肠炎的作用。在肥胖诱导胰岛素抵抗的小鼠模型中,Joseph等[13]发现益生菌来源的胞壁酰二肽能有效提高小鼠胰岛对葡萄糖的利用。

尽管研究探讨了益生菌后生元在许多肠道菌群紊乱相关疾病中的治疗效果,但是很少有研究探讨肝硬化相关的肠道菌群紊乱中,后生元的预防和治疗作用。在最近的一项研究中,Zhou等[67]发现丁酸梭菌对高脂膳食诱导的非酒精性肝炎小鼠有很好的治疗效果,可改善非酒精性肝炎小鼠肠道菌群紊乱的情况,进一步研究发现丁酸梭菌的治疗作用是通过分泌丁酸而实现,其机制可能是促进了CD4+ T细胞向Th2、Th22和Treg细胞分化,抑制CD4+ T细胞向Th1或Th17分化等肠肝免疫调节;有趣的是,直接向非酒精性肝炎小鼠补充丁酸盐可以改善肠道菌群紊乱并增强肠道屏障的功能,起到很好的治疗非酒精性肝炎效果。由此可见,后生元对于调节肝硬化肠道菌群紊乱、进而改善肠道菌群失调相关的疾病进程及并发症有广泛的应用前景。

3 总结和展望肝硬化患者出现感染、腹水、肝性脑病等并发症是导致其短期死亡、增加疾病负担的重要原因,肠道菌群失调在肝硬化的疾病进展中有重要的作用。益生菌是目前治疗肝硬化肠道菌群失调、调节疾病进程的重要研究方向,其存在一定效果的同时,也出现许多争议,作为一种活菌体,很难计量益生菌在肠道中的生物利用度,因此,其临床最佳使用剂量和疗程也不明确。此外,益生菌的安全性和耐药基因传递性一直是业界探讨的主要热点问题。后生元是一类具有类似益生菌益生功效的益生菌产物,在近几年受到越来越多的关注,它具有维持肠道菌群、保护肠屏障功能、免疫调节等多种作用。相比于活菌体,其最大的优点在于具有明确的化学结构、良好的吸收性和分布性。使用后生元能在发挥益生菌益生功效的同时,避免活菌体的诸多缺点,为肝硬化及其并发症的治疗指明了新的方向。然而,就目前而言,后生元指的是发挥益生菌功效的益生菌所有组分的统称,在概念上仍然难以界定和分类。在后生元获取与成分鉴定方面,还需要克服许多技术性的难题,以便系统全面地得到所需后生元进行进一步研究;在菌属选择方面,除了从常见的益生菌如乳杆菌及双歧杆菌提取并鉴定后生元以外,结合肝硬化肠道菌群失调特征,从其他非常见菌属入手,也有望分离鉴定出有良好治疗功效的后生元。后生元的作用效果及机制多样,对分离鉴定出的后生元进行作用机制的探索,能帮助我们更好地了解肠道菌群与宿主之间的关系,为后生元走向临床应用打好基础。就目前而言,对后生元的研究仍然处于起步阶段,其在肝硬化中的研究还不成熟,需要进行大量的、系统性的基础研究进行探索,结合后期的临床试验进行验证。因此,后生元在肝硬化治疗中的研究还需克服许多理论和技术上的难题,需要对其活性、作用机制等进行进一步的研究、分析和归纳。通过系统性地探究后生元益生功效,整合优化和合理利用各种益生组分,有可能实现对肝硬化肠道菌群紊乱的精准治疗。

| [1] | Long B, Koyfman A. The emergency medicine evaluation and management of the patient with cirrhosis. The American Journal of Emergency Medicine, 2018, 36(4): 689-698. DOI:10.1016/j.ajem.2017.12.047 |

| [2] | Olson JC. Intensive care management of patients with cirrhosis. Current Treatment Options in Gastroenterology, 2018, 16(2): 241-252. DOI:10.1007/s11938-018-0182-2 |

| [3] |

Yu SL, Gong YL, Shao RT, Wu GY. Study on burden of diseases of chronic hepatitis B, virrhosis and liver cancer caused by hepatitis B virus. China Public Health, 2003, 19(3): 280-282.

(in Chinese) 于淑丽, 龚幼龙, 邵瑞太, 武桂英. 慢性乙肝、乙肝后肝硬化和肝癌的疾病负担. 中国公共卫生, 2003, 19(3): 280-282. |

| [4] | Piano S, Brocca A, Mareso S, Angeli P. Infections complicating cirrhosis. Liver International: Official Journal of the International Association for the Study of the Liver, 2018, 38 Suppl 1: 126-133. |

| [5] | Macnaughtan J, Jalan R. Clinical and pathophysiological consequences of alterations in the microbiome in cirrhosis. The American Journal of Gastroenterology, 2015, 110(10): 1399-1410. DOI:10.1038/ajg.2015.313 |

| [6] | Riordan SM, Williams R. The intestinal flora and bacterial infection in cirrhosis. Journal of Hepatology, 2006, 45(5): 744-757. DOI:10.1016/j.jhep.2006.08.001 |

| [7] | Bajaj JS, Heuman DM, Hylemon PB, Sanyal AJ, White MB, Monteith P, Noble NA, Unser AB, Daita K, Fisher AR, Sikaroodi M, Gillevet PM. Altered profile of human gut microbiome is associated with cirrhosis and its complications. Journal of Hepatology, 2014, 60(5): 940-947. DOI:10.1016/j.jhep.2013.12.019 |

| [8] | Albillos A, Lario M, Álvarez-Mon M. Cirrhosis-associated immune dysfunction: Distinctive features and clinical relevance. Journal of Hepatology, 2014, 61(6): 1385-1396. DOI:10.1016/j.jhep.2014.08.010 |

| [9] | Lin CY, Tsai IF, Ho YP, Huang CT, Lin YC, Lin CJ, Tseng SC, Lin WP, Chen WT, Sheen IS. Endotoxemia contributes to the immune paralysis in patients with cirrhosis. Journal of Hepatology, 2007, 46(5): 816-826. DOI:10.1016/j.jhep.2006.12.018 |

| [10] | Bajaj JS, Ridlon JM, Hylemon PB, Thacker LR, Heuman DM, Smith S, Sikaroodi M, Gillevet PM. Linkage of gut microbiome with cognition in hepatic encephalopathy. American Journal of Physiology-Gastrointestinal and Liver Physiology, 2012, 302(1): G168-G175. DOI:10.1152/ajpgi.00190.2011 |

| [11] | Riordan SM, Williams R. Gut flora and hepatic encephalopathy in patients with cirrhosis. The New England Journal of Medicine, 2010, 362(12): 1140-1142. DOI:10.1056/NEJMe1000850 |

| [12] | Fukui H. Gut microbiome-based therapeutics in liver cirrhosis: Basic consideration for the next step. Journal of Clinical and Translational Hepatology, 2017, 5(3): 249-260. |

| [13] | Cavallari JF, Fullerton MD, Duggan BM, Foley KP, Denou E, Smith BK, Desjardins EM, Henriksbo BD, Kim KJ, Tuinema BR, Stearns JC, Prescott D, Rosenstiel P, Coombes BK, Steinberg GR, Schertzer JD. Muramyl dipeptide-based postbiotics mitigate obesity-induced insulin resistance via IRF4. Cell Metabolism, 2017, 25(5): 1063-1074. DOI:10.1016/j.cmet.2017.03.021 |

| [14] | Tsilingiri K, Barbosa T, Penna G, Caprioli F, Sonzogni A, Viale G, Rescigno M. Probiotic and postbiotic activity in health and disease: comparison on a novel polarised ex-vivo organ culture model. Gut, 2012, 61(7): 1007-1015. DOI:10.1136/gutjnl-2011-300971 |

| [15] | Chen YF, Yang FL, Lu HF, Wang BH, Chen YB, Lei DJ, Wang YZ, Zhu BL, Li LJ. Characterization of fecal microbial communities in patients with liver cirrhosis. Hepatology, 2011, 54(2): 562-572. DOI:10.1002/hep.24423 |

| [16] | Qin N, Yang FL, Li A, Prifti E, Chen YF, Shao L, Guo J, Le Chatelier E, Yao J, Wu LJ, Zhou JW, Ni SJ, Liu L, Pons N, Batto JM, Kennedy SP, Leonard P, Yuan CH, Ding WC, Chen YT, Hu XJ, Zheng BW, Qian GR, Xu W, Ehrlich SD, Zheng SS, Li LJ. Alterations of the human gut microbiome in liver cirrhosis. Nature, 2014, 513(7516): 59-64. DOI:10.1038/nature13568 |

| [17] | Macnaughtan J, Davies N, Stadlbauer V, Damink SWO, Mookerjee RP, Jalan R. Evidence for compartmentalised endotoxemia and its effect on neutrophil function in the portal circulation in cirrhosis. Meeting of the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases, 2010, 52(4): 342A-343A. |

| [18] | Mookerjee RP, Stadlbauer V, Lidder S, Wright GAK, Hodges SJ, Davies NA, Jalan R. Neutrophil dysfunction in alcoholic hepatitis superimposed on cirrhosis is reversible and predicts the outcome. Hepatology, 2007, 46(3): 831-840. DOI:10.1002/(ISSN)1527-3350 |

| [19] | Hackstein CP, Assmus LM, Welz M, Klein S, Schwandt T, Schultze J, Förster I, Gondorf F, Beyer M, Kroy D, Kurts C, Trebicka J, Kastenmüller W, Knolle PA, Abdullah Z. Gut microbial translocation corrupts myeloid cell function to control bacterial infection during liver cirrhosis. Gut, 2017, 66(3): 507-518. DOI:10.1136/gutjnl-2015-311224 |

| [20] | Chen YF, Guo J, Qian GR, Fang DQ, Shi D, Guo LH, Li LJ. Gut dysbiosis in acute-on-chronic liver failure and its predictive value for mortality. Journal of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, 2015, 30(9): 1429-1437. DOI:10.1111/jgh.2015.30.issue-9 |

| [21] | Shawcross DL, Shabbir SS, Taylor NJ, Hughes RD. Ammonia and the neutrophil in the pathogenesis of hepatic encephalopathy in cirrhosis. Hepatology, 2010, 51(3): 1062-1069. DOI:10.1002/hep.v51:3 |

| [22] | Butterworth RF. The liver-brain axis in liver failure: neuroinflammation and encephalopathy. Nature Reviews Gastroenterology & Hepatology, 2013, 10(9): 522-528. |

| [23] | Dhiman RK, Sawhney IMS, Chawla YK, Das G, Ram S, Dilawari JB. Efficacy of lactulose in cirrhotic patients with subclinical hepatic encephalopathy. Digestive Diseases and Sciences, 2000, 45(8): 1549-1552. DOI:10.1023/A:1005556826152 |

| [24] | Bajaj JS, Heuman DM, Sanyal AJ, Hylemon PB, Sterling RK, Stravitz RT, Fuchs M, Ridlon JM, Daita K, Monteith P, Noble NA, White MB, Fisher A, Sikaroodi M, Rangwala H, Gillevet PM. Modulation of the metabiome by rifaximin in patients with cirrhosis and minimal hepatic encephalopathy. PLoS One, 2013, 8(4): e60042. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0060042 |

| [25] | Alexopoulou A, Papadopoulos N, Eliopoulos DG, Alexaki A, Tsiriga A, Toutouza M, Pectasides D. Increasing frequency of Gram-positive cocci and Gram-negative multidrug-resistant bacteria in spontaneous bacterial peritonitis. Liver International, 2013, 33(7): 975-981. DOI:10.1111/liv.2013.33.issue-7 |

| [26] | Fern ndez J, Navasa M, Planas R, Montoliu S, Monfort D, Soriano G, Vila C, Pardo A, Quintero E, Vargas V, Such J, Ginès P, Arroyo V. Primary prophylaxis of spontaneous bacterial peritonitis delays hepatorenal syndrome and improves survival in cirrhosis. Gastroenterology, 2007, 133(3): 818-824. DOI:10.1053/j.gastro.2007.06.065 |

| [27] | Deshpande A, Pasupuleti V, Thota P, Pant C, Mapara S, Hassan S, Rolston DDK, Sferra TJ, Hernandez AV. Acid-suppressive therapy is associated with spontaneous bacterial peritonitis in cirrhotic patients: A meta-analysis. Journal of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, 2013, 28(2): 235-242. DOI:10.1111/jgh.2013.28.issue-2 |

| [28] | Kwon JH, Koh SJ, Kim W, Jung YJ, Kim JW, Kim BG, Lee KL, Im JP, Kim YJ, Kim JS, Yoon JH, Lee HS, Jung HC. Mortality associated with proton pump inhibitors in cirrhotic patients with spontaneous bacterial peritonitis. Journal of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, 2014, 29(4): 775-781. DOI:10.1111/jgh.2014.29.issue-4 |

| [29] | Lunia MK, Sharma BC, Sharma P, Sachdeva S, Srivastava S. Probiotics prevent hepatic encephalopathy in patients with cirrhosis: A randomized controlled trial. Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology, 2014, 12(6): 1003-1008. DOI:10.1016/j.cgh.2013.11.006 |

| [30] | Rincón D, Vaquero J, Hernando A, Galindo E, Ripoll C, Puerto M, Salcedo M, Francés R, Matilla A, Catalina MV, Clemente G, Such J, Bañares R. Oral probiotic VSL#3 attenuates the circulatory disturbances of patients with cirrhosis and ascites. Liver International, 2014, 34(10): 1504-1512. DOI:10.1111/liv.2014.34.issue-10 |

| [31] | Liu Q, Duan ZP, Ha DK, Bengmark S, Kurtovic J, Riordan SM. Synbiotic modulation of gut flora: effect on minimal hepatic encephalopathy in patients with cirrhosis. Hepatology, 2004, 39(5): 1441-1449. DOI:10.1002/(ISSN)1527-3350 |

| [32] | Saji S, Kumar S, Thomas V. A randomized double blind placebo controlled trial of probiotics in minimal hepatic encephalopathy. Tropical Gastroenterology: Official Journal of the Digestive Diseases Foundation, 2011, 32(2): 128-132. |

| [33] | Rayes N, Seehofer D, Theruvath T, Schiller RA, Langrehr JM, Jonas S, Bengmark S, Neuhaus P. Supply of pre- and probiotics reduces bacterial infection rates after liver transplantation—a randomized, double-blind trial. American Journal of Transplantation, 2005, 5(1): 125-130. DOI:10.1111/ajt.2005.5.issue-1 |

| [34] | Sherid M, Samo S, Sulaiman S, Husein H, Sifuentes H, Sridhar S. Liver abscess and bacteremia caused by lactobacillus: role of probiotics? Case report and review of the literature. Bmc Gastroenterology, 2016, 16: 138. DOI:10.1186/s12876-016-0552-y |

| [35] | Besselink MG, van Santvoort HC, Buskens E, Boermeester MA, van Goor H, Timmerman HM, Nieuwenhuijs VB, Bollen TL, van Ramshorst B, Witteman BJ, Rosman C, Ploeg RJ, Brink MA, Schaapherder AF, Dejong CH, Wahab PJ, van Laarhoven CJ, van der Harst E, van Eijck CH, Cuesta MA, Akkermans LM, Gooszen HG. Probiotic prophylaxis in predicted severe acute pancreatitis: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet (London, England), 2008, 371(9613): 651-659. |

| [36] | Lebeer S, Bron PA, Marco ML, van Pijkeren JP, O'Connell Motherway M, Hill C, Pot B, Roos S, Klaenhammer T. Identification of probiotic effector molecules: present state and future perspectives. Current Opinion in Biotechnology, 2017, 49: 217-223. |

| [37] | Aguilar-Toalá JE, Garcia-Varela R, Garcia HS, Mata-Haro V, González-Córdova AF, Vallejo-Cordoba B, Hernández-Mendoza A. Postbiotics: An evolving term within the functional foods field. Trends in Food Science & Technology, 2018, 75: 105-114. |

| [38] | Shenderov BA. Metabiotics: novel idea or natural development of probiotic conception. Microbial Ecology in Health & Disease, 2013, 24: 20399. |

| [39] | Sahadeva RPK, Leong SF, Chua KH, Tan CH, Chan HY, Tong EV, Wong SY, Chan HK. Survival of commercial probiotic strains to pH and bile. International Food Research Journal, 2011, 18(4): 1515-1522. |

| [40] | Kareem KY, Ling FH, Chwen LT, Foong OM, Asmara SA. Inhibitory activity of postbiotic produced by strains of Lactobacillus plantarum using reconstituted media supplemented with inulin. Gut Pathogens, 2014, 6(1): 23. DOI:10.1186/1757-4749-6-23 |

| [41] | Yu J, Wang WH, Menghe BLG, Jiri MT, Wang HM, Liu WJ, Bao QH, Lu Q, Zhang JC, Wang F, Xu HY, Sun TS, Zhang HP. Diversity of lactic acid bacteria associated with traditional fermented dairy products in Mongolia. Journal of Dairy Science, 2011, 94(7): 3229-3241. DOI:10.3168/jds.2010-3727 |

| [42] | Turner DL, Lamosa P, Rodríguez A, Martínez B. Structure and properties of the metastable bacteriocin Lcn972 from Lactococcus lactis. Journal of Molecular Structure, 2013, 1031: 207-210. DOI:10.1016/j.molstruc.2012.09.076 |

| [43] | Sassone-Corsi M, Nuccio SP, Liu H, Hernandez D, Vu CT, Takahashi AA, Edwards RA, Raffatellu M. Microcins mediate competition among Enterobacteriaceae in the inflamed gut. Nature, 2016, 540(7632): 280-283. DOI:10.1038/nature20557 |

| [44] | Levy M, Thaiss CA, Zeevi D, Dohnalová L, Zilberman-Schapira G, Mahdi JA, David E, Savidor A, Korem T, Herzig Y, Pevsner-Fischer M, Shapiro H, Christ A, Harmelin A, Halpern Z, Latz E, Flavell RA, Amit I, Segal E, Elinav E. Microbiota-modulated metabolites shape the intestinal microenvironment by regulating NLRP6 inflammasome signaling. Cell, 2015, 163(6): 1428-1443. DOI:10.1016/j.cell.2015.10.048 |

| [45] | He XL, Zeng Q, Puthiyakunnon S, Zeng ZJ, Yang WJ, Qiu JW, Du L, Boddu S, Wu TW, Cai DX, Huang SH, Cao H. Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG supernatant enhance neonatal resistance to systemic Escherichia coli K1 infection by accelerating development of intestinal defense. Scientific Reports, 2017, 7: 43305. DOI:10.1038/srep43305 |

| [46] | Yan F, Liu LP, Dempsey PJ, Tsai YH, Raines EW, Wilson CL, Cao HL, Cao Z, Liu LS, Polk DB. A Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG-derived soluble protein, p40, stimulates ligand release from intestinal epithelial cells to transactivate epidermal growth factor receptor. The Journal of Biological Chemistry, 2013, 288(42): 30742-30751. DOI:10.1074/jbc.M113.492397 |

| [47] | Pelaseyed T, Bergström JH, Gustafsson JK, Ermund A, Birchenough GMH, Schütte A, van der Post S, Svensson F, Rodríguez-Piñeiro AM, Nyström EEL, Wising C, Johansson MEV, Hansson GC. The mucus and mucins of the goblet cells and enterocytes provide the first defense line of the gastrointestinal tract and interact with the immune system. Immunological Reviews, 2014, 260(1): 8-20. DOI:10.1111/imr.2014.260.issue-1 |

| [48] | Macpherson AJ, McCoy KD, Johansen FE, Brandtzaeg P. The immune geography of IgA induction and function. Mucosal Immunology, 2008, 1(1): 11-22. DOI:10.1038/mi.2007.6 |

| [49] | Möndel M, Schroeder BO, Zimmermann K, Huber H, Nuding S, Beisner J, Fellermann K, Stange EF, Wehkamp J. Probiotic E. coli treatment mediates antimicrobial human β-defensin synthesis and fecal excretion in humans. Mucosal Immunology, 2008, 2(2): 166-172. |

| [50] | Yoda K, Miyazawa K, Hosoda M, Hiramatsu M, Yan F, He F. Lactobacillus GG-fermented milk prevents DSS-induced colitis and regulates intestinal epithelial homeostasis through activation of epidermal growth factor receptor. European Journal of Nutrition, 2014, 53(1): 105-115. DOI:10.1007/s00394-013-0506-x |

| [51] | Yan F, Cao HW, Cover TL, Washington MK, Shi Y, Liu LS, Chaturvedi R, Peek RM Jr, Wilson KT, Polk DB. Colon-specific delivery of a probiotic-derived soluble protein ameliorates intestinal inflammation in mice through an EGFR-dependent mechanism. The Journal of Clinical Investigation, 2011, 121(6): 2242-2253. DOI:10.1172/JCI44031 |

| [52] | Corridoni D, Pastorelli L, Mattioli B, Locovei S, Ishikawa D, Arseneau KO, Chieppa M, Cominelli F, Pizarro TT. Probiotic bacteria regulate intestinal epithelial permeability in experimental ileitis by a TNF-dependent mechanism. PLoS One, 2012, 7(7): e42067. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0042067 |

| [53] | Wang YH, Kirpich I, Liu YL, Ma ZH, Barve S, McClain CJ, Feng WK. Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG treatment potentiates intestinal hypoxia-inducible factor, promotes intestinal integrity and ameliorates alcohol-induced liver injury. The American Journal of Pathology, 2011, 179(6): 2866-2875. DOI:10.1016/j.ajpath.2011.08.039 |

| [54] | Wang YH, Liu YL, Sidhu A, Ma ZH, McClain C, Feng WK. Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG culture supernatant ameliorates acute alcohol-induced intestinal permeability and liver injury. American Journal of Physiology-Gastrointestinal and Liver Physiology, 2012, 303(1): G32-G41. DOI:10.1152/ajpgi.00024.2012 |

| [55] | Prisciandaro LD, Geier MS, Chua AE, Butler RN, Cummins AG, Sander GR, Howarth GS. Probiotic factors partially prevent changes to caspases 3 and 7 activation and transepithelial electrical resistance in a model of 5-fluorouracil-induced epithelial cell damage. Supportive Care in Cancer, 2012, 20(12): 3205-3210. DOI:10.1007/s00520-012-1446-3 |

| [56] | von Schillde MA, Hörmannsperger G, Weiher M, Alpert CA, Hahne H, B uerl C, van Huynegem K, Steidler L, Hrncir T, Pérez-Martínez G, Kuster B, Haller D. Lactocepin secreted by Lactobacillus exerts anti-inflammatory effects by selectively degrading proinflammatory chemokines. Cell Host & Microbe, 2012, 11(4): 387-396. |

| [57] | Mazmanian SK, Round JL, Kasper DL. A microbial symbiosis factor prevents intestinal inflammatory disease. Nature, 2008, 453(7195): 620-625. DOI:10.1038/nature07008 |

| [58] | Ménard S, Candalh C, Bambou JC, Terpend K, Cerf-Bensussan N, Heyman M. Lactic acid bacteria secrete metabolites retaining anti-inflammatory properties after intestinal transport. Gut, 2004, 53(6): 821-828. DOI:10.1136/gut.2003.026252 |

| [59] | Hoarau C, Lagaraine C, Martin L, Velge-Roussel F, Lebranchu Y. Supernatant of Bifidobacterium breve induces dendritic cell maturation, activation, and survival through a Toll-like receptor 2 pathway. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology, 2006, 117(3): 696-702. DOI:10.1016/j.jaci.2005.10.043 |

| [60] | Hoarau C, Martin L, Faugaret D, Baron C, Dauba A, Aubert-Jacquin C, Velge-Roussel F, Lebranchu Y. Supernatant from Bifidobacterium differentially modulates transduction signaling pathways for biological functions of human dendritic cells. PLoS One, 2008, 3(7): e2753. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0002753 |

| [61] | Xu RH, Shang N, Li PL. In vitro and in vivo antioxidant activity of exopolysaccharide fractions from Bifidobacterium animalis RH. Anaerobe, 2011, 17(5): 226-231. DOI:10.1016/j.anaerobe.2011.07.010 |

| [62] | Li W, Ji J, Chen XH, Jiang M, Rui X, Dong MS. Structural elucidation and antioxidant activities of exopolysaccharides from Lactobacillus helveticus MB2-1. Carbohydrate Polymers, 2014, 102: 351-359. DOI:10.1016/j.carbpol.2013.11.053 |

| [63] | Lebeer S, Claes IJJ, Vanderleyden J. Anti-inflammatory potential of probiotics: lipoteichoic acid makes a difference. Trends in Microbiology, 2012, 20(1): 5-10. DOI:10.1016/j.tim.2011.09.004 |

| [64] | Dinić M, Lukić J, Djokić J, Milenković M, Strahinić I, Golić N, Begović J. Lactobacillus fermentum postbiotic-induced autophagy as potential approach for treatment of acetaminophen hepatotoxicity. Frontiers in Microbiology, 2017, 8: 594. |

| [65] | Sharma M, Shukla G. Metabiotics: One step ahead of probiotics; an insight into mechanisms involved in anticancerous effect in colorectal cancer. Frontiers in Microbiology, 2016, 7: 1940. |

| [66] | Sokol H, Pigneur B, Watterlot L, Lakhdari O, Bermúdez-Humarán LG, Gratadoux JJ, Blugeon S, Bridonneau C, Furet JP, Corthier G, Grangette C, Vasquez N, Pochart P, Trugnan G, Thomas G, Blottière HM, Doré J, Marteau P, Seksik P, Langella P. Faecalibacterium prausnitzii is an anti-inflammatory commensal bacterium identified by gut microbiota analysis of Crohn disease patients. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 2008, 105(43): 16731-16736. DOI:10.1073/pnas.0804812105 |

| [67] | Zhou D, Pan Q, Shen F, Cao HX, Ding WJ, Chen YW, Fan JG. Total fecal microbiota transplantation alleviates high-fat diet-induced steatohepatitis in mice via beneficial regulation of gut microbiota. Scientific Reports, 2017, 7(1): 1529. DOI:10.1038/s41598-017-01751-y |

2018, Vol. 58

2018, Vol. 58