中国科学院微生物研究所,中国微生物学会,中国菌物学会

文章信息

- 张媛, 李春燕, 谢建平. 2017

- Yuan Zhang, Chunyan Li, Jianping Xie. 2017

- 分枝杆菌毒素——分枝杆菌内酯与布鲁里溃疡

- Mycolactone: the toxin of Mycobacterium and Buruli ulcer

- 微生物学报, 57(7): 961-968

- Acta Microbiologica Sinica, 57(7): 961-968

-

文章历史

- 收稿日期:2016-10-25

- 修回日期:2017-01-21

- 网络出版日期:2017-02-22

生物毒素是由动物、植物、微生物等产生的有毒物质,生物活性复杂,可对人体生理功能产生重大影响。细菌毒素属于微生物毒素,是生物毒素的重要组成部分。布鲁里溃疡(Buruli ulcer,BU)是由溃疡分枝杆菌(Mycobacterium ulcerans,MU)感染所导致的慢性皮肤坏死疾病,在非洲西部农村发病率很高[1],却未被广泛重视。BU感染初期会使皮肤组织出现肿块,随后表现出典型的溃疡损伤,与其他致病性分枝杆菌巨噬细胞胞内致病性不同,MU会在受损细胞外聚集并扩大损伤部位。1999年,从MU的脂溶培养物中提取并纯化到一种脂类细胞毒性分子分枝杆菌内酯,可以使L929小鼠纤维母细胞发生病变[2]。分枝杆菌内酯是一种聚酮类代谢产物[3],对细菌的毒力十分重要。BU感染后,分枝杆菌内酯可以扩散至哺乳动物细胞的细胞质,并造成细胞凋亡[4],导致免疫抑制和组织坏死,同时也是BU患者在溃疡部位丧失痛感的原因[5]。此外,贴壁依赖性细胞最容易受到分枝杆菌内酯的攻击,会造成其细胞骨架重排和分离[6-7]。中国也是布鲁里溃疡的发病地区之一,但是并没有受到关注,目前没有关于我国发生此病的详细有效资料与报道。目前已经有一些国内文章[8-10]对MU的致病性和分枝杆菌内酯的合成有所介绍,本文将以分枝杆菌毒素——分枝杆菌内酯为切入点,对其结构、毒性作用、分子靶点等进行更加全面的综述,介绍近年来对分枝杆菌内酯的毒性机制研究取得的新进展。

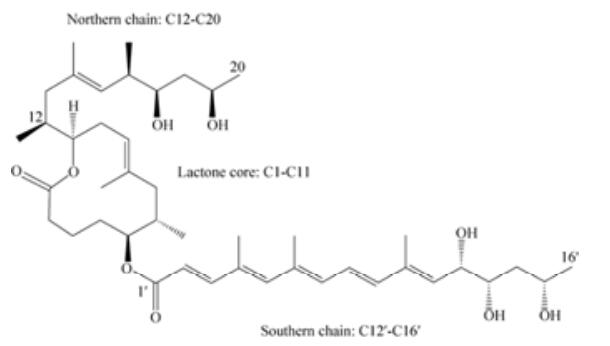

1 分枝杆菌内酯的结构及合成来源于非洲、澳大利亚和中国的人类致病性MU分别主要产生分枝杆菌内酯A/B,分枝杆菌内酯C和分枝杆菌内酯D,同时每种菌株可以产生少量的另外2种同类物,且体外绝大多数细胞毒性同系物为分枝杆菌内酯A/B[11],分子式C44H70O9 (图 1)。分枝杆菌内酯是一种含十二元内酯环(C1-C11) 的聚酮物,两端连接高度不饱和酰基侧链。上方短侧链由C12-C20组成,下方长侧链为C1′-C16′,短侧链性质稳定一般不发生变化,而长侧链可以通过一些结构改变产生不同的分枝杆菌内酯同类物,且在普通实验室条件下分枝杆菌内酯可以围绕C4′C5′双键以3:2的比率自发形成几何异构体[2]。此外,长侧链上羟基的位置差异会引起生物活性的不同。

|

| 图 1 分枝杆菌内酯A/B化学结构 Figure 1 Chemical structure of mycolactone A/B. |

聚酮类化合物是由低级脂肪酸聚合而成的长碳链结构产物,合成过程中需要聚酮合酶(polyketide synthases,PKSs)的催化。分枝杆菌内酯的合成依赖于一种174 kb的大质粒pMUM001,它包含3个大基因mlsA1 (51 kb)、mlsA2 (7.2 kb)和mlsB (43 kb),编码模块化Ⅰ型聚酮合成酶(type Ⅰ modular polyketide synthase)、聚酮修饰酶(polyketide-modifying enzymes)和一些辅助基因[12],这些功能区域包括脂酰基转移酶、酮类还原酶、脱水酶、酰基载体蛋白、酰基转移酶、烯酰还原酶、硫酯酶、环化酶等聚酮物质合成所需的与结构和碳链长度有关的酶系[13-14]。MlsA1和MslA2形成模块复合物合成分枝杆菌内酯的核心,MlsB为单一多肽用于侧链合成,辅助蛋白基因比如mup038、mup045、mup053则与加入亚基有关,分别编码酰基转移酶、Ⅱ型硫酯酶和加氧酶,负责催化和羟化内酯核心和侧链[15-16]。

2 分枝杆菌内酯的分子靶点 2.1 通过Sec61抑制共转译多肽链易位Sec61是一种内质网膜蛋白转位因子,可以与易位子相关蛋白(translocon associated protein complex,TRAP)和寡糖基转移酶(oligosaccharyltransferase,OST)形成复合物,负责将蛋白转运进出内质网[17](endoplasmic reticulum,ER)。不结合核糖体的Sec61采用横向封闭构象,当结合核糖体进行多肽链转移时,横向Sec61α亚基将会开启并进行之后的运输工作[18],其共转译多肽链运输机制与翻译后又有所不同[19]。大多数在ER转移的蛋白会进行共转录易位,即核糖体通过Sec61配件蛋白和信号肽依附于内质网膜,翻译中的多肽合成后直接通过伴侣蛋白进入内质网腔进行折叠[20]。Sec61是分枝杆菌内酯的一个作用目标位点,分枝杆菌内酯可以调整Sec61的构象[19],阻碍其转移多肽链,而停留在胞浆中翻译的蛋白则由于被蛋白酶标记而迅速分解(图 2-A),其中具体的机制仍有待进一步研究。这一作用虽然不影响α因子前体、IL-6、COX-2(内质网标记酶)、β内酰胺酶、肿瘤坏死因子和血栓调节蛋白(Ⅰ型膜蛋白)的翻译,但其在内质网的运输将会受阻进而影响这些细胞因子最终的产量[21-22]。

|

| 图 2 分枝杆菌内酯作用机制 Figure 2 Mechanism of action of Mycolactone. A: inhibition of Sec61 translation; B: hyperactivation of WASP. |

2.2 Wiskott-Aldrich综合症蛋白的超活化

分枝杆菌内酯导致体外培养的细胞进行细胞骨架重排并分离。分枝杆菌内酯与Wiskott-Aldrich综合症蛋白(Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome protein,WASP)和神经WASP (Neural WASP,N-WASP)直接结合,改变了肌动蛋白动力学[23]。Arp2/3属于肌动蛋白相关蛋白,能使微丝核化并促进新的微丝生成;WASP和N-WASP属于支架蛋白家族,其C末端VCA区域(verprolin-cofilin-acidic)通过分子内相互作用呈自抑制状态,激活后可与Arp2/3复合物作用,向肌动蛋白传递信息进行细胞骨架动态重构[24]。分枝杆菌内酯可以阻截肌动蛋白核化因子,干扰WASP自抑制使其超活化,导致Arp2/3介导的胞浆肌动蛋白转配激活失控,使其在核周围区域聚集造成细胞在粘附和定向迁移方面的缺陷(图 2-B)。分枝杆菌内酯结合N-WASP的强度是其主要调节子CDC42的100倍[25],并可以抑制N-WASP抑制因子的作用,强烈刺激肌动蛋白在体内装配的能力。此外,研究发现WASP发生突变可以通过减弱基因组稳定性来促进T淋巴细胞的凋亡,且WASP是Th1基因表达的表观遗传调节因子[26-28]。

3 分枝杆菌内酯的细胞毒性作用 3.1 免疫细胞在机体对抗分枝杆菌感染的过程中,单核细胞和巨噬细胞发挥着重要作用。分枝杆菌内酯可以影响J774巨噬细胞的吞噬作用[29],还通过抑制吞噬泡的成熟和氮氧产物的产生来改变巨噬细胞的抑菌活性[30],而对于细胞因子、趋化因子和其他分泌免疫调节器等胞内效应分子则呈现出剂量依赖型抑制[21]。分枝杆菌内酯在50 ng/mL浓度以上时,会使树突细胞对细胞凋亡敏感,低于此浓度时会影响其成熟与迁移活性但不改变其吞噬作用活性,且对树突细胞响应Toll样受体配基诱导产生的趋化因子的分泌有明显的选择作用[31]。分枝杆菌还可以抑制T细胞产生IL-2,抗原依赖性产物Th-1、Th-2和Th-17也相应减少[32]。T细胞归巢过程可以被分枝杆菌内酯强烈影响,因为皮下施用分枝杆菌内酯会造成T细胞在外周淋巴结大量消耗[33],这与归巢受体L选择素(L-selectin)的缺陷表达有关,可能是因为ER蛋白易位运输受到阻碍。此外,不被易位阻碍影响的组分也会受到分枝杆菌内酯的影响,例如microRNA中let-6减少会促进T细胞的凋亡[34]。

3.2 皮肤组织细胞皮肤组织中有多种类型细胞,包括纤维母细胞、内皮细胞、脂肪细胞、角质细胞和肌肉细胞等。L929小鼠纤维母细胞对于分枝杆菌内酯敏感,浓度在0.025 ng/mL时,12 h会发生细胞病变和骨架重排,24 h造成细胞结聚,48 h脱离培养皿[35],可能是WASP (Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome protein)超活化造成,在高浓度15 μg/mL时,分枝杆菌内酯会导致细胞通透性快速改变而发生细胞原发性坏死[29]。在脂肉瘤的SW872人类细胞系中研究发现,这些细胞对1 μg/mL的分枝杆菌内酯相对长期耐受,5 d会发生低水平凋亡和稍高水平的坏死[36],造成细胞毒性的组分可能是一些脂蛋白复合物。原代微血管内皮细胞对于7 ng/mL的低浓度分枝杆菌内酯高度敏感[37],24 h会导致细胞耗尽表面凝血剂受体血栓调节蛋白,3-4 d死亡。分枝杆菌内酯对角质形成细胞的细胞毒性与活性氧ROS的快速生成有关,可以通过ROS抑制物去铁胺进行抑制[38]。BU病变形成肿块时患者会丧失病变处的痛觉,这可能与皮肤组织中的神经细胞有关。在小鼠模型中进行测试,MU感染感染小鼠脚垫5-7周发现降低肿胀处的痛觉,而随着时间增长发生糜烂和溃疡时痛觉有所恢复。最近研究发现,分枝杆菌毒素并不通过破坏神经束造成痛觉丧失,而是依赖于AT2Rs (type 2 angiotensin Ⅱ receptors)基因的表达[39],以血管紧张肽通络为靶点,导致神经元产生钾离子依赖性超极化,可能是潜在的镇痛药物靶点。但是,又有研究发现分枝杆菌内酯可以引起大鼠DRG (dorsal root ganglia)神经的毒性作用,导致其变性和死亡[40]。因此,分枝杆菌内酯是否损伤神经造成其退化仍存在争议。

4 挑战与未来研究趋势在体外,溃疡分枝杆菌对利福平、氨基糖苷类、大环内酯类和喹诺酮类药物敏感。十几年来,布鲁里溃疡治疗方案多使用利福平和链霉素联合治疗8周以上[41]。有研究发现,链霉素和利福平治疗2周后,使用利福平联合克拉霉素可以代替利福平和链霉素进行延续阶段的治疗而治疗效果没有降低,完全口服利福平和克拉霉素8周也可以达到预期效果[42],且此治疗方式可以口服而不需要注射,因此可以减少患者治疗时的痛苦。值得注意的是,有时候抗生素治疗时会出现溃疡病情加重的现象,可能是因为治疗失败或者治疗有效使患者本身的免疫反应有所恢复[43]。

布鲁里溃疡作为非洲西部高发病率疾病,其无痛特性往往使患者忽略其严重性而延缓治疗时间,不利于及时治疗和疾病控制。抗生素治疗的效果也不稳定,会发生治疗失败或者免疫恢复而导致溃疡部位免疫恶化的情况。因此,进行有效快速而合理的治疗十分重要。分枝杆菌毒素分枝杆菌内酯是溃疡分枝杆菌感染引起布鲁里溃疡的关键物质,对分枝杆菌内酯进行研究,有助于对布鲁里溃疡进行监测、诊断和药物治疗。分枝杆菌内酯导致的痛觉丧失是否涉及神经细胞损伤和退化,将小鼠细胞阻滞在G0/G1期[2]的分子机理仍然有待研究。受分枝杆菌内酯影响,WASP和Arp2/3可能改变细胞骨架组分如肌动蛋白和微丝的集束化,改变细胞正常的分裂和分化[44],例如N-WASP功能异常可以影响小鼠卵母细胞分裂,抑制中间体的形成造成第二次减数分裂的失败[45]。不同于结核分枝杆菌和麻风分枝杆菌,溃疡分枝杆菌具有独特的胞外致病性,分枝杆菌内酯的存在是这一特性的主要原因。因此,深入对分枝杆菌内酯的研究有利于研究分枝杆菌家族的进化、毒性和致病机制。目前已经发现了可以有效中和小鼠分枝杆菌毒素毒性的抗体[46],表明干扰素-γ在小鼠对溃疡分枝杆菌感染免疫发挥重要作用[47], 今后控制布鲁里溃疡的措施应该仍以分枝杆菌内酯为主要切入点,可以从小分子药物、抗体等角度继续深入研究。同时,希望能出现对我国布鲁里溃疡流行地区情况的报道与预防策略的展开,加强全民健康意识和疾病防控。

| [1] | O'Brien DP, Comte E, Serafini M, Ehounou G, Antierens A, Vuagnat H, Christinet V, Hamani MD, du Cros P. The urgent need for clinical, diagnostic, and operational research for management of Buruli ulcer in Africa. The Lancet Infectious Diseases, 2014, 14(5): 435-440. DOI:10.1016/S1473-3099(13)70201-9 |

| [2] | Sarfo FS, Phillips R, Wansbrough-Jones M, Simmonds RE. Recent advances:role of mycolactone in the pathogenesis and monitoring of Mycobacterium ulcerans infection/Buruli ulcer disease. Cellular Microbiology, 2016, 18(1): 17-29. DOI:10.1111/cmi.12547 |

| [3] | Demangel C, Stinear TP, Cole ST. Buruli ulcer:reductive evolution enhances pathogenicity of Mycobacterium ulcerans. Nature Reviews Microbiology, 2009, 7(1): 50-60. DOI:10.1038/nrmicro2077 |

| [4] | Hong H, Demangel C, Pidot SJ, Leadlay PF, Stinear T. Mycolactones:immunosuppressive and cytotoxic polyketides produced by aquatic mycobacteria. Natural Product Reports, 2008, 25(3): 447-454. DOI:10.1039/b803101k |

| [5] | Goto M, Nakanaga K, Aung T, Hamada T, Yamada N, Nomoto M, Kitajima S, Ishii N, Yonezawa S, Saito H. Nerve damage in Mycobacterium ulcerans-infected mice:probable cause of painlessness in Buruli ulcer. The American Journal of Pathology, 2006, 168(3): 805-811. DOI:10.2353/ajpath.2006.050375 |

| [6] | Bozzo C, Tiberio R, Graziola F, Pertusi G, Valente G, Colombo E, Small PLC, Leigheb G. A Mycobacterium ulcerans toxin, mycolactone, induces apoptosis in primary human keratinocytes and in HaCaT cells. Microbes and Infection, 2010, 12(14/15): 1258-1263. |

| [7] | Snyder DS, Small PLC. Uptake and cellular actions of mycolactone, a virulence determinant for Mycobacterium ulcerans. Microbial Pathogenesis, 2003, 34(2): 91-101. DOI:10.1016/S0882-4010(02)00210-3 |

| [8] |

Li Y, Zhang JZ. Advances in Buruli ulcer disease. The Journal of the Chinese Antituberculosis Association, 2004, 26(5): 298-300.

(in Chinese) 李妍, 张建中. Buruli溃疡病研究进展. 中国防痨杂志, 2004, 26(5): 298-300. |

| [9] |

Yang ZS. A new less noticeable infectious disease:Mycobacterium ulcerans infection (Buruli ulcer). Chinese Journal of Microecology, 2011, 23(3): 283-288.

(in Chinese) 杨正时. 不太引人注目的新发感染病:溃疡分枝杆菌感染(Buruli溃疡). 中国微生态学杂志, 2011, 23(3): 283-288. |

| [10] |

Yang ZS. Mycobacterium ulcerans, mycobacillin and toxin of Mycobacterium ulcerans. Chinese Journal of Microecology, 2010, 22(12): 1150-1152.

(in Chinese) 杨正时. 溃疡分枝杆菌、溃疡分枝杆菌素与溃疡分枝杆菌毒素. 中国微生态学杂志, 2010, 22(12): 1150-1152. |

| [11] | Mve-Obiang A, Lee RE, Portaels F, Small PLC. Heterogeneity of mycolactones produced by clinical isolates of Mycobacterium ulcerans:implications for virulence. Infection and Immunity, 2003, 71(2): 774-783. DOI:10.1128/IAI.71.2.774-783.2003 |

| [12] | Stinear TP, Mve-Obiang A, Small PLC, Frigui W, Pryor MJ, Brosch R, Jenkin GA, Johnson PDR, Davies JK, Lee RE, Adusumilli S, Garnier T, Haydock SF, Leadlay PF, Cole ST. Giant plasmid-encoded polyketide synthases produce the macrolide toxin of Mycobacterium ulcerans. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 2004, 101(5): 1345-1349. DOI:10.1073/pnas.0305877101 |

| [13] | Perić-Concha N, Borovička B, Long PF, Hranueli D, Waterman PG, Hunter IS. Ablation of the otcC gene encoding a post-polyketide hydroxylase from the oxytetracyline biosynthetic pathway in Streptomyces rimosus results in novel polyketides with altered chain length. The Journal of Biological Chemistry, 2005, 280(45): 37455-37460. DOI:10.1074/jbc.M503191200 |

| [14] | Ridley CP, Lee HY, Khosla C. Evolution of polyketide synthases in bacteria. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 2008, 105(12): 4595-4600. DOI:10.1073/pnas.0710107105 |

| [15] | Porter JL, Tobias NJ, Hong H, Tuck KL, Jenkin GA, Stinear TP. Transfer, stable maintenance and expression of the mycolactone polyketide megasynthase mls genes in a recombination-impaired Mycobacterium marinum. Microbiology, 2009, 155(Pt 6): 1923-1933. |

| [16] | Stinear TP, Pryor MJ, Porter JL, Cole ST. Functional analysis and annotation of the virulence plasmid pMUM001 from Mycobacterium ulcerans. Microbiology, 2005, 151(Pt 3): 683-692. |

| [17] | Pfeffer S, Dudek J, Gogala M, Schorr S, Linxweiler J, Lang S, Becker T, Beckmann R, Zimmermann R, Förster F. Structure of the mammalian oligosaccharyl-transferase complex in the native ER protein translocon. Nature Communications, 2014, 5: 3072. |

| [18] | Pfeffer S, Förster F. Sec61:a static framework for membrane-protein insertion. Channels, 2016, 10(3): 167-169. DOI:10.1080/19336950.2015.1125737 |

| [19] | McKenna M, Simmonds RE, High S. Mechanistic insights into the inhibition of Sec61-dependent co- and post-translational translocation by mycolactone. Journal of Cell Science, 2016, 129(7): 1404-1415. DOI:10.1242/jcs.182352 |

| [20] | Zimmermann R, Eyrisch S, Ahmad M, Helms V. Protein translocation across the ER membrane. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA)-Biomembranes, 2011, 1808(3): 912-924. DOI:10.1016/j.bbamem.2010.06.015 |

| [21] | Hall BS, Hill K, McKenna M, Ogbechi J, High S, Willis AE, Simmonds RE. The pathogenic mechanism of the Mycobacterium ulcerans virulence factor, mycolactone, depends on blockade of protein translocation into the ER. PLoS Pathogens, 2014, 10(4): e1004061. DOI:10.1371/journal.ppat.1004061 |

| [22] | Simmonds RE, Lali FV, Smallie T, Small PLC, Foxwell BM. Mycolactone inhibits monocyte cytokine production by a posttranscriptional mechanism. The Journal of Immunology, 2009, 182(4): 2194-2202. DOI:10.4049/jimmunol.0802294 |

| [23] | Guenin-Macé L, Veyron-Churlet R, Thoulouze MI, Romet-Lemonne G, Hong H, Leadlay PF, Danckaert A, Ruf MT, Mostowy S, Zurzolo C, Bousso P, Chrétien F, Carlier MF, Demangel C. Mycolactone activation of wiskott-aldrich syndrome proteins underpins Buruli ulcer formation. Journal of Clinical Investigation, 2013, 123(4): 1501-1512. DOI:10.1172/JCI66576 |

| [24] | Thrasher AJ, Burns SO. WASP:a key immunological multitasker. Nature Reviews Immunology, 2010, 10(3): 182-192. DOI:10.1038/nri2724 |

| [25] | Leung DW, Rosen MK. The nucleotide switch in Cdc42 modulates coupling between the GTPase-binding and allosteric equilibria of Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome protein. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 2005, 102(16): 5685-5690. DOI:10.1073/pnas.0406472102 |

| [26] | Boulkroun S, Guenin-Macé L, Thoulouze MI, Monot M, Merckx A, Langsley G, Bismuth G, Di Bartolo V, Demangel C. Mycolactone suppresses T cell responsiveness by altering both early signaling and posttranslational events. The Journal of Immunology, 2010, 184(3): 1436-1444. DOI:10.4049/jimmunol.0902854 |

| [27] | Taylor MD, Sadhukhan S, Kottangada P, Ramgopal A, Sarkar K, D'Silva S, Selvakumar A, Candotti F, Vyas YM. Nuclear role of WASp in the pathogenesis of dysregulated TH1 immunity in human Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome. Science Translational Medicine, 2010, 2(37): 37ra44. |

| [28] | Westerberg LS, Meelu P, Baptista M, Eston MA, Adamovich DA, Cotta-de-Almeida V, Seed B, Rosen MK, Vandenberghe P, Thrasher AJ, Klein C, Alt FW, Snapper SB. Activating WASP mutations associated with X-linked neutropenia result in enhanced actin polymerization, altered cytoskeletal responses, and genomic instability in lymphocytes. The Journal of Experimental Medicine, 2010, 207(6): 1145-1152. DOI:10.1084/jem.20091245 |

| [29] | Adusumilli S, Mve-Obiang A, Sparer T, Meyers W, Hayman J, Small PLC. Mycobacterium ulcerans toxic macrolide, mycolactone modulates the host immune response and cellular location of M. ulcerans in vitro and in vivo. Cellular Microbiology, 2005, 7(9): 1295-1304. DOI:10.1111/j.1462-5822.2005.00557.x |

| [30] | Torrado E, Fraga AG, Logarinho E, Martins TG, Carmona JA, Gama JB, Carvalho MA, Proença F, Castro AG, Pedrosa J. IFN-γ-dependent activation of macrophages during experimental infections by Mycobacterium ulcerans is impaired by the toxin mycolactone. The Journal of Immunology, 2010, 184(2): 947-955. DOI:10.4049/jimmunol.0902717 |

| [31] | Coutanceau E, Decalf J, Martino A, Babon A, Winter N, Cole ST, Albert ML, Demangel C. Selective suppression of dendritic cell functions by Mycobacterium ulcerans toxin mycolactone. The Journal of Experimental Medicine, 2007, 204(6): 1395-1403. DOI:10.1084/jem.20070234 |

| [32] | Phillips R, Sarfo FS, Guenin-Macé L, Decalf J, Wansbrough-Jones M, Albert ML, Demangel C. Immunosuppressive signature of cutaneous Mycobacterium ulcerans infection in the peripheral blood of patients with buruli ulcer disease. The Journal of Infectious Diseases, 2009, 200(11): 1675-1684. DOI:10.1086/599183 |

| [33] | Guenin-Macé L, Carrette F, Asperti-Boursin F, Le Bon A, Caleechurn L, Di Bartolo V, Fontanet A, Bismuth G, Demangel C. Mycolactone impairs T cell homing by suppressing microRNA control of L-selectin expression. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 2011, 108(31): 12833-12838. DOI:10.1073/pnas.1016496108 |

| [34] | Ham O, Lee SY, Lee CY, Park JH, Lee J, Seo HH, Cha MJ, Choi E, Kim S, Hwang KC. let-7b suppresses apoptosis and autophagy of human mesenchymal stem cells transplanted into ischemia/reperfusion injured heart by targeting caspase-3. Stem Cell Research & Therapy, 2015, 6(1): 147. |

| [35] | George KM, Chatterjee D, Gunawardana G, Welty D, Hayman J, Lee R, Small PLC. Mycolactone:a polyketide toxin from Mycobacterium ulcerans required for virulence. Science, 1999, 283(5403): 854-857. DOI:10.1126/science.283.5403.854 |

| [36] | Dobos KM, Small PL, Deslauriers M, Quinn FD, King CH. Mycobacterium ulcerans cytotoxicity in an adipose cell model. Infection and Immunity, 2001, 69(11): 7182-7186. DOI:10.1128/IAI.69.11.7182-7186.2001 |

| [37] | Ogbechi J, Ruf MT, Hall BS, Bodman-Smith K, Vogel M, Wu HL, Stainer A, Esmon CT, Ahnström J, Pluschke G, Simmonds RE. Mycolactone-dependent depletion of endothelial cell thrombomodulin is strongly associated with fibrin deposition in buruli ulcer lesions. PLoS Pathogens, 2015, 11(7): e1005011. DOI:10.1371/journal.ppat.1005011 |

| [38] | Grönberg A, Zettergren L, Bergh K, Ståhle M, Heilborn J, Ängeby K, Small PL, Akuffo H, Britton S. Antioxidants protect keratinocytes against M. ulcerans mycolactone cytotoxicity. PLoS One, 2010, 5(11): e13839. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0013839 |

| [39] | Marion E, Song OR, Christophe T, Babonneau J, Fenistein D, Eyer J, Letournel F, Henrion D, Clere N, Paille V, Guérineau NC, Saint André JP, Gersbach P, Altmann KH, Stinear TP, Comoglio Y, Sandoz G, Preisser L, Delneste Y, Yeramian E, Marsollier L, Brodin P. Mycobacterial toxin induces analgesia in Buruli ulcer by targeting the angiotensin pathways. Cell, 2014, 157(7): 1565-1576. DOI:10.1016/j.cell.2014.04.040 |

| [40] | Anand U, Sinisi M, Fox M, MacQuillan A, Quick T, Korchev Y, Bountra C, McCarthy T, Anand P. Mycolactone-mediated neurite degeneration and functional effects in cultured human and rat DRG neurons:mechanisms underlying hypoalgesia in Buruli ulcer. Molecular Pain, 2016, 12: 1744806916654144. |

| [41] | Johnson PDR, Hayman JA, Quek TY, Fyfe JAM, Jenkin GA, Buntine JA, Athan E, Birrell M, Graham J, Lavender CJ. Consensus recommendations for the diagnosis, treatment and control of Mycobacterium ulcerans infection (Bairnsdale or Buruli ulcer) in Victoria, Australia. The Medical Journal of Australia, 2007, 186(2): 64-68. |

| [42] | Phillips RO, Sarfo FS, Abass MK, Abotsi J, Wilson T, Forson M, Amoako YA, Thompson W, Asiedu K, Wansbrough-Jones M. Clinical and bacteriological efficacy of rifampin-streptomycin combination for two weeks followed by rifampin and clarithromycin for six weeks for treatment of Mycobacterium ulcerans disease. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy, 2014, 58(2): 1161-1166. DOI:10.1128/AAC.02165-13 |

| [43] | Barogui YT, Klis SA, Johnson RC, Phillips RO, van der Veer E, van Diemen C, van der Werf TS, Stienstra Y. Genetic susceptibility and predictors of paradoxical reactions in buruli ulcer. PLoS Neglected Tropical Diseases, 2016, 10(4): e0004594. DOI:10.1371/journal.pntd.0004594 |

| [44] | Allwood EG, Tyler JJ, Urbanek AN, Smaczynska-de Rooij Ⅱ, Ayscough KR. Elucidating key motifs required for Arp2/3-dependent and independent actin nucleation by Las17/WASP. PLoS One, 2016, 11(9): e0163177. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0163177 |

| [45] | Wang ZB, Ma XS, Hu MW, Jiang ZZ, Meng TG, Dong MZ, Fan LH, Ouyang YC, Snapper SB, Schatten H, Sun QY. Oocyte-specific deletion of N-WASP does not affect oocyte polarity, but causes failure of meiosis Ⅱ completion. Molecular Human Reproduction, 2016, 22(9): 613-621. DOI:10.1093/molehr/gaw046 |

| [46] | Dangy JP, Scherr N, Gersbach P, Hug MN, Bieri R, Bomio C, Li J, Huber S, Altmann KH, Pluschke G. Antibody-mediated neutralization of the exotoxin mycolactone, the main virulence factor produced by Mycobacterium ulcerans. PLoS Neglected Tropical Diseases, 2016, 10(6): e0004808. DOI:10.1371/journal.pntd.0004808 |

| [47] | Bieri R, Bolz M, Ruf MT, Pluschke G. Interferon-γ is a crucial activator of early host immune defense against Mycobacterium ulcerans infection in mice. PLoS Neglected Tropical Diseases, 2016, 10(2): e0004450. DOI:10.1371/journal.pntd.0004450 |

2017, Vol. 57

2017, Vol. 57